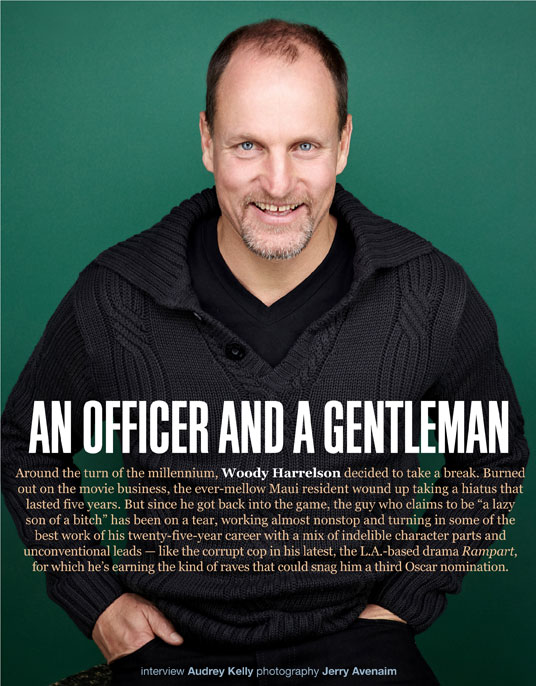

Since then he has worked steadily, balancing the leading roles in indies like The Walker and studio films like Zombieland with scene-stealing supporting parts in hits like No Country for Old Men and 2012, and doing some of the best work in a career already marked by knockout performances in films like Natural Born Killers and The People vs. Larry Flynt.

Two of his most compelling turns have come in collaboration with Oren Moverman, the Israeli-born writer-director of the 2009 drama The Messenger, in which Harrelson played a troubled Army sergeant assigned to the Casualty Notification Team, and Rampart, co-written by novelist James Ellroy, in which Harrelson stars as a rule-flouting L.A. cop whose years of blithe corruption finally catch up with him. He scored his second Oscar nomination for The Messenger (the first came in 1997 for The People vs. Larry Flynt), and his raw Rampart performance is generating buzz that could put him back in the running for a third time.

Not bad for a guy who could have settled for a cushy TV career playing endearing dimwits in the mold of Woody Boyd, his character on the classic sitcom Cheers. Instead, he defied typecasting to become one of the most reliable — and reliably unpredictable — movie actors of the past quarter-century.

Yet for some reason, despite the Oscar nods and a resume that includes films by such marquee directors as Adrian Lyne (Indecent Proposal), Oliver Stone (Natural Born Killers), Milos Forman (The People vs. Larry Flynt), Barry Levinson (Wag the Dog), Ron Howard (EDtv), Terrence Malick (The Thin Red Line), Spike Lee (She Hate Me), Robert Altman (A Prairie Home Companion), Paul Schrader (The Walker) and the Coen Brothers (No Country for Old Men), Harrelson remains something of a stealth star — ubiquitous yet overlooked, talented but taken for granted.

But his body of work, and the range of his performances — from the goofy to the poignant to the terrifying — are as impressive as those of anyone in the business. Oliver Stone, who has always been believer, says, “Woody has become one of our most authentic actors. He also happens to have a great social conscience — too bad he can’t afford a political life.”

Looking at the fifty-year-old actor’s upcoming schedule, Stone seems to have a point. In March of 2012, Harrelson will appear in one of the most anticipated films of the year, The Hunger Games, based on the hugely popular young-adult novel by Suzanne Collins, in which he plays Haymitch Abernathy, the drunken mentor to Katniss Everdeen, a contestant in one of the futuristic saga’s death-matches, played by Winter’s Bone’s Jennifer Lawrence. It’s a role that is sure to put Harrelson in high demand.

Before he’s swept up by the adolescent demo that made the Twilight series a global smash, Fade In caught up with Harrelson on the set of Seven Psychopaths, playwright-turned-filmmaker Martin McDonagh’s follow-up to In Bruges, about a dog-napping gone wrong. Relaxed and talkative, Harrelson expounded on his career and recent projects, as well as his frustration with contemporary politics and memorable run-ins with Gloria Steinem and Quentin Tarantino.

One ended in a friendship — the other, not so much.

Mickey Rourke was set to play your character in Seven Psychopaths. How did he fall out and you fall in? Well, it was really lucky for me because he wasn’t content with the deal. He kept pressing on the deal until finally they were like, “Why don’t we go somewhere else?” They started to come to me earlier [than that], and my agent was going to send me the script really quick, but then they were like, “No, no. Everything is fine [with Rourke’s deal]. He’s back in.” That’s when I was in Europe. At the time, although I would have liked to have worked with Martin and this frigging phenomenal cast, I was ready for a break, and just ready to go home. I’d been away from home for a while, so I wasn’t really thinking that much about it. Then I get a “Read this thing urgently!” [Laughs] So I lucked out.

So from the time you read the script to start of production it was…? Two weeks. Martin comes from a stage background.

How is his approach to filmmaking different for you as an actor? Well, one thing that’s pretty major is, he likes it to be word-perfect, as opposed to most films, you can mess around. I like to improvise. He likes it to be just like the theatre, where every word is exactly the same. But I’ve done quite a lot of theatre. I came from theatre. So I can respect that, and I knew, I had heard it. So it’s OK. Although sometimes you really want to just mix it up a little, you know?

I’ve known him a long time. I was actually hanging out with him when he was writing [the play] The Pillowman. He would tell me some of the stuff that was going on, and I’d just be like, [feigns surprise]. I tried to convince him to go with John Crowley as a director, and he did. Then he offered me Pillowman. I read it, and went, “Dude, the darkness has finally outshone the light on this one.” It really was so dark. So I go see it in New York. One of the best productions I’ve ever seen. I was so disappointed in myself for not taking the part. That’s why when this was offered, I took it seriously. I’m not going to make the same fuck-up twice, and go see this movie and say, “Why didn’t I do it?”

A lot of people probably don’t know that you write, direct, produce and star in plays. Yeah, well, I’m finally getting on it. But this play we did earlier this year in Toronto — that was a great experience. So more of that. I’m trying to find the perfect hole in my schedule next year to do one in New York by September. It’s called Bullet for Adolf. [Laughs] The title will let you know what you’re in for…not in terms of Adolf — he doesn’t appear — but it will challenge you.

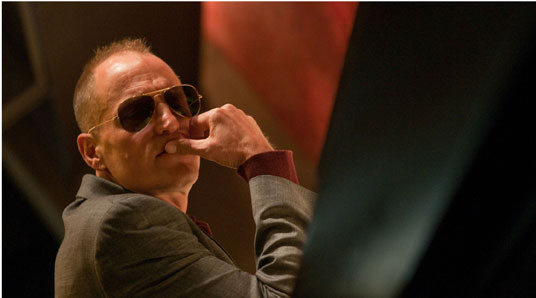

“In a way, I feel like my character [in Rampart] would have gone Mafia if he hadn’t gone bad cop. He probably has a lot of respect for certain Mafia figures, like Mickey Cohen. So the clothes were modeled after Dean Martin, and even the drink that I got in the film was Martin’s drink. He’d have a gin martini with two olives.”

“I always know when there’s been a school shooting. I’ll see them play a scene from Natural Born Killers on the news. And I’m always like, ‘Oh boy.’ Then they’re talking about violence in the media. Of course, they don’t show any images of antidepressants and people don’t widely know that without exception every one of those kids involved in those school shootings are on antidepressants.”

Did you write that one? Yeah, I co-wrote it.

It really sounds like you don’t have much downtime. Maybe you like it that way? No, honestly, I don’t. I’m a lazy son of a bitch. I don’t like working at all. I prefer to be home with the fam’, living in Maui. I’m really a hippie at heart. Just the way everything’s come down. It’s not like I really wanted to plan it this way. There’s not much down time. Definitely in the next year, not much down time. But after that, maybe. You know, I’m prone to take a year or two off. I’m not afraid to do that. Well, I’m a little bit afraid. Nah, I’m lying. The last time I did it I felt was a short attention span.

That was five years, right? Yeah, it was pretty much five years, but I did a couple little things for friends, and I did do theatre each year during that time. I was really just wanting to get back to the basics. I was not feeling that connected to the process of making a movie. I wasn’t enjoying it.

Why? Because I had done it so many times in a row, and I really just started feeling exhausted by it. You know, it is a pretty rigorous schedule.

You were carrying the films, too, as a leading man. Yeah, then you do all the press. I just had to stop for a while because if you’re not appreciating this job, then there’s something seriously wrong with you. You know, everybody would like to do this job. I don’t know anyone who wouldn’t want to do this job. Even rock stars and politicians sometimes want to do this job, so… I don’t know. I needed to take that break, and I really did it to amp up my appreciation for what it is. Since I started doing that again, which is now a number of years ago, I’ve appreciated things more. And it was a good thing. I needed to spend time with the fam’ and chill for awhile.

Did you plan on five years, though? It really just turned into five years. I was thinking two or three, but once you’re in it…pretty groovy. I’m a hard worker. World-class slacker, though.

So this long break was after The People vs. Larry Flynt? Actually, I did Welcome to Sarajevo right after. Old Harvey Weinstein, who can talk the skin off a snake, somehow talked me into going and doing that, but made it into a kind of a vacation-y thing, and that I was staying on an island off Italy with my family. Go in, shoot, come straight back. So made it a little easier, but yeah, after that, I was done for a while.

How did the controversy with Natural Born Killers affect you and/or your career? It was terrible.

And it’s still controversial today, which is bizarre. Yeah it’s one of those things where… I always know when there’s been a school shooting. I’ll see them play a scene from Natural Born Killers on the news. And I’m always like, “Oh, boy.” Then they’re talking about violence in the media. Of course, they don’t show any images of antidepressants, and people don’t widely know that without exception, every one of those kids involved in those school shootings are on antidepressants. It was bad because there was that, and then there was the whole controversy around Larry Flynt. Then there was the whole controversy around Money Train, believe it or not. Because there’s a scene where fuel was injected into the ticket booth in the subway, and lighting it on fire, and then someone did that, and they said it was a copycat thing. So it was like, bam bam bam. I was just so… No, wait. That came before Larry Flynt, yeah. So Natural Born Killers, then the Money Train controversy — which, you know, I didn’t love that movie anyway – then Larry Flynt, which I really had my heart into, and was so invested emotionally. Everyone worked so hard on it. So for Gloria Steinem to go around the country and tell women to make sure they don’t see it, and to make sure their husbands don’t see it… that hurt. That hurt. You want people to see the movies you do, you know?

It’s hard to understand why people can’t see it just as a movie. There’s nothing you can do about that. But ironic that a woman like Gloria Steinem, who used to give names to the FBI of anti-war people… She was this person who was so revered, and she could hang out with anybody and they’d be glad to be hanging out with her and think she’d be on their side. No, she’s giving names to the FBI. She’s a lonely woman. I met her one time with Paul McCartney. It was in New York, not long after I did Zombieland. And I knew this whole thing she did, which someone paid her to do it. But who knows who that was. I have an idea, but anyway, she had literally gone and wrote a letter to the New York Times editor, and she went around the country, city to city. She did better PR than we did. Her minions brought her up to the table to say hi to Paul. And Paul goes, “This is Woody.” She extends her hand out to me and I go, “Gloria…?” And she says, “Steinem.” I said, “I have no respect for you.” And I didn’t shake her hand. So, in typical Gloria Steinem style, she — or her people, more likely — call [New York Post gossip column] Page Six and tell them that I stood up in the restaurant and came toward her shouting, “You ruined my career!” Total bullshit! Just a completely fabricated story. Unbelievable. Of course, we refuted it, so I don’t know what they ran, but certainly hers was juicier. But it was just a big lie.

Good for you. Yeah. Oh, I have no respect for her. Even if she hadn’t done that, I know what she did. She’s never been outed properly about what she did giving up anti-war protestors’ names. Nobody knows it. But enough about her.

So when you came back from your sabbatical, you started to do more character work, which has really been some of your best. Did not being the leading man help you enjoy the work more? Yeah. I definitely don’t have a thing where I need to be the center of the film. A part can be a good part, and an interesting part, and that’s how I started. I started with supporting roles, and I’ve never felt like I shouldn’t do a role because it’s a supporting role. I suppose some people do feel that way. I don’t feel that way at all. I feel lucky if it’s a cool role in a good movie, you know?

Having said that, I don’t think I’d do a supporting role in a play.

Why not? I want to be on that frigging stage.

You seem to shift effortlessly between studio films and indies, but you said before we sat down that the independents were much more meaningful to you. Why? I’d definitely say my heart’s with the indies. There’s some good studio movies. Larry Flynt was a studio movie, but it’s like theatre in L.A. If you’re doing theatre in L.A., you gotta give a shit about theatre, which is ironically why you find a lot of good theatre in L.A. Indies are the same thing. If you’re doing indie movies. then you really must care. It’s not a monetary payoff, or anything like that.

You have to really care about the project.

“But ironic that a woman like Gloria Steinem, who used to give names to the FBI of anti-war people… She was this person who was so revered and she could hang out with anybody and they’d be glad to be hanging out with her and think she’d be on their side. No, she’s giving names to the FBI. She’s a lonely women.”

“I’d definitely say my heart’s with the indies. There’s some good studio movies. Larry Flynt was a studio movie but it’s like theatre in L.A. If you’re doing theatre in L.A. you gotta give a shit about theatre, which is ironically why you find a lot of good theatre in L.A..”

Rampart is an indie. What it is about Oren that made you want to work with him again? Well, he’s become a really good buddy of mine, so it’s like working with my brother almost. But a brother you really get along great with. Just the way he directs…first, he hands you a script, and the words are already as good as it gets. He helps you with backstory. He outlines the area where you’re going to be working and leaves you a big space. In other words, he doesn’t say “OK, you’re going to come in, and you’re going to sit in this chair, you’re going to drink that…” Nothing’s locked in. There’s no rehearsal. I don’t want to sit here and encourage Oren to keep up that crazy policy, but you come in and you haven’t even talked with the other actors. It’s just like you’re in your character, they’re in their character, and you just see what happens.

And he does encourage you to improvise, and try stuff, and experiment. He’ll say, “Fuck it, if you want to walk off screen and come back, do it. Do whatever you want.” And so he gives you so much freedom, and also so much great direction. You feel like you’re part of the creative soup, and you know you have this guy overlooking it that won’t let you fail. So, in other words, you let yourself fail. Let yourself be as bad as you want to be. God knows he must have tons of footage of me just being terrible, trying shit, because he’s up for the game. He’s up for anything. He’ll make it right. And then, if you are going off, he’ll come up and he’ll give you just the right words. Almost like…what do you call those four-line poems? [Quatrains.] Just so unbelievably articulate in not even his first language. The way that he can say just the right thing to make you go, “Oh, yeah! I got it. Let me try it again.” If I had to sign a contract that says I’m only doing Oren’s movies, one a year for the rest of my life, I’d just be like, “Sure.” I’d have to scale down my expenses.

That sounds like a fun set. It is fun, but it’s a serious set. There are laughs, but there’s a serious intention where Oren almost infuses the love of the project in everybody. Every person in the crew is invested. I don’t know. It’s hard to describe it.

Well, the chemistry is on the screen. The performances, directing, cinematographer… It all comes across. So there was something special in that soup, as you call it. Yes, there is. And [cinematographer] Bobby Bukowski is a key component. He and Oren are a match made in heaven and then Bobby does stuff that is so…he’s also freestyling. He’s improvising as he goes. The camera, particularly in Rampart, is always in motion. He locked it down for maybe two shots the whole film. Otherwise, it was handheld or it was held from a bungee cord that they’d invented, that I’d never seen.

It was reported that you weren’t happy with the initial cut of the film. Why? Yeah. I saw it in May, and I thought it was terrible. I was depressed, depressed beyond words. Because one thing I knew for certain when I was shooting this movie was, this is a great movie. I’d have bet anybody. I knew it was a great movie. So I go to see it in May, and it was drastically changed. Three-dozen scenes cut, major characters cut or diminished. So a part of my reaction was just my expectation of what the script was. The ending and the build-up to the ending, they’re all different.

So therein began a period of time where there was real difficulty between me and Oren. I almost want to look up all these emails because there were times when he was like, “Dude, we can’t sacrifice our friendship over this.” And I was like, “Dude, I want you to know one thing — you are my buddy forever.” And I really meant that, you know? It was a really traumatic time because I loved that movie so much. I just gave everything to it. I didn’t want to leave. You know how they say, the term “spend it”? Well I didn’t want to leave anything unspent. So when I saw it, and was so disappointed… whew, it was a tough few months. Then it was accepted to Toronto [Film Festival]. I love Toronto. It’s one of my favorite cities in North America. I was like, “Are they out of their fucking mind?! Digging this movie?”

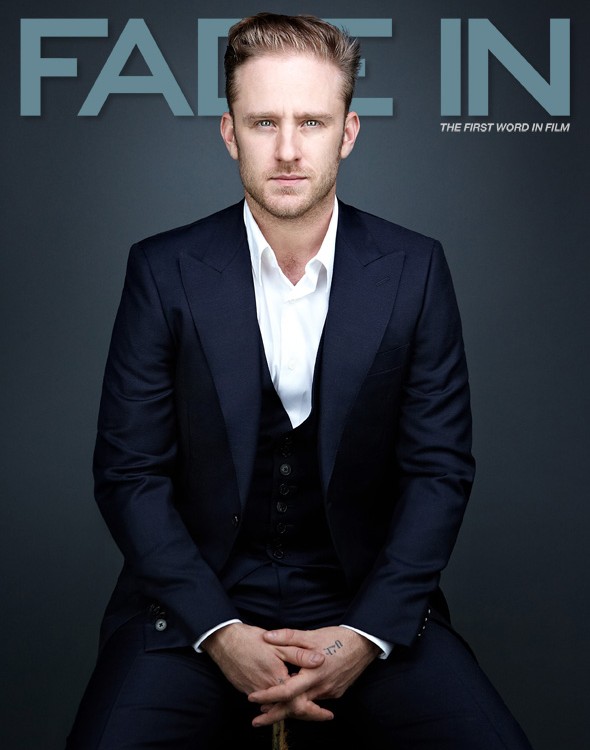

Was it the same cut? Well, it couldn’t have been. I don’t know how much of it was the same, but in Toronto, they accepted it. I got word, “Well, will you go?” “No. I’m not going to support this movie.” Then I got a call from Ben Foster — who’s also like my brother — saying, “Hey, you got to man up. This is family. We’re going to Toronto.”

Now it’s August, and I’m shooting Hunger Games. Then I went to New York to look at theaters and meet general managers, so I’ve had a long day doing that, and they ask me to go see the movie again at the end of that day. And I was already exhausted, but I thought, “OK, I’m going to suck it up and go.” And there’s [producer] Ken [Kao], Oren and [producer] Lawrence [Inglee], and they’re all there for my reaction. [Laughs] I watch the frigging movie, and the first ten minutes I’m thinking to myself, “These first ten minutes are so good. I just have to remember where it goes south.” Twenty minutes, thirty minutes, forty-five minutes…and then we get to the end of it, and I’m like, “Oh my God!” I walked up to Oren. He’s sitting in the back of the theatre, kind of squatted down against the wall, and I said, “Oren, it takes a man to admit he was wrong. And I have to admit I was completely wrong. This movie’s great, dude.” Then he started crying, and I started crying, and we’re down on the floor hugging each other,so happy to be feeling the same way. It’s almost like having a child or something. And I realized I was wrong, and a lot of it had to do with expectations, and what was there before. I realized he’s not only a great director, he went into the editing room and proved he’s a great sculptor. It wouldn’t have worked, the way it was shot. And he molded that into something different. It’s a different movie, but fantastic. So innovative. Almost like some of those seventies movies. It has that kind of vibe. But, yeah, we had to go through it to get to it on that one.

It’s also been reported that you lost thirty pounds for the role. Well, twenty-nine. to be exact.

Why drop that much weight? Well, an actor talking about his process is about as boring of a thing as I can imagine. Like, they asked Brando if he thought acting was art and he said no. And I believe he wasn’t even sure if movies were art. But he was a harsh critic. Having said that, I will tell you because I felt like a component of this guy that I found interesting…you know. You have to find what aspects of the character relate to who you are, and then you fantasize the other aspects…and so one of them was this concept of having trouble with accepting affection and accepting love from women, which I feel is a central thing. He loves women — loves ’em — but has a lot of trouble accepting love. So I made this analogy, and it actually does probably work sometimes this way in life, where my inability to eat is almost like my inability to accept love. I’m not letting myself get nourished through the food, or through the love from a woman. So I thought that was a good reason. I actually was a little more interested in Christian Bale’s weight [when he did The Machinist]. I wanted to get down to that, but now I think that would have been wrong. It would have been too much about that. You know what I mean? From the time I started really investing myself more as an actor, like in college, as opposed to before, where I’d just get up and say the lines, I always would work from the outside in. I’d think more about the look. In this case, the way he dressed. In my mind, my character was a big fan of Dean Martin. I was listening almost exclusively and constantly to Dean Martin while I was doing the movie. And that kind of connects to the whole Mafia thing. In a way, I feel like my character would have gone Mafia if he hadn’t gone bad cop. So he probably has a lot of respect for certain Mafia figures, like Mickey Cohen. So the clothes were modeled after Dean Martin, and even the drink that I got in the film was Dean Martin’s drink. He’d have a gin martini with two olives. So the one scene in the very beginning, where I come in and I’m like, “Where’s the olives?” that actually happened. I had actually gotten upset because they didn’t have olives there.

Did playing or researching the role give you a new understanding of the vocation? Yeah, definitely. Hanging out with cops in researching the part, it was almost like the last time Oren and I made a movie, where I spent a lot of time with army people, and I really came to appreciate them. So on this thing, I found some really cool cops. And the guys who were working directly with me…I was on patrol with them quite a bit. Then, even outside of that, we’d have dinner, or have some other cops come, or the higher-ups. And even though I have a place in L.A., I stayed in an apartment downtown where Oren, Ken and Ben were staying. So being downtown was helpful. I don’t know. There are some really good guys, really good guys. And, you know, they don’t make much money. They gotta give a shit. Sometimes there are power-hungry guys, but that’s a small minority who make those decisions and give a bad name to cops.

Like these cops macing kids at UC Davis. Fucking bullshit. That doesn’t reflect most cops. Then you don’t know if they were simply following orders to do that. A lot of times, they’ll do what they’ve been ordered to do. Same way with the military. One thing’s for sure, they follow orders. So it’s not always a bad cop, although in the case of UC Davis, it’s hard to imagine what the fuck those guys were thinking. They were nonviolent protesters. Ninety percent of the guys I met were fantastic.

So you don’t feel portraying a bad cop, even though based on an actual person, could negatively influence cops you may run into outside of L.A.? I’m not portraying Serpico. You know what I mean? That’d be a great role, but this is a different guy. On the other hand, I’m interested in characters who are not entirely good or not entirely heroic. More antihero characters, like Larry Flynt, or in Natural Born Killers or Rampart. Nobody is all good. If you can watch that, and find compassion for that character — and that is really a part of what happens with some people watching Rampart, in spite of whatever actions the character may have done, they find themselves caring for the character. To me, that’s a lot more interesting.

So you’re not worried? You mean that cops will mess with me because of it? No, I don’t think so. Cops will be like, “Hey, that’s not how we are. You’re going to jail”? I hope not. [Laughs]

What was the most difficult part during production? The most difficult was trying to get rid of any trace of my Southern accent. That was hard. Harder than losing thirty pounds. That was fucking hard. I thought of myself as sounding fairly neutral. [Laughs] Not at all. I got Southern in my speech, mannerisms. It’s so ingrained, you know? So I had to use a coach. I didn’t want my character to be Southern. You know, I did that with The Messenger. That character was very Southern. I actually made myself more Southern.

Which film do you feel you learned the most from? Probably The Messenger. It really meant a lot to me spending time with those soldiers. What the government always tried to do with the commercials and posters is get you to lump in the warriors with the war. Because they know you’ll care about the warriors, even though you may not care for the war. Well, I always, in my mind, lumped them together. I didn’t have grievance with the soldiers, but I just lumped them in with the war at large, so spending that time, and getting to hang out with those soldiers, and finding that these are some of the finest individuals that I’ve ever met… Risking their lives for almost no money, and doing it out of a love for their country, and wanting to do a good thing. They’re not the ones who dictate foreign policy. That’s unfortunately been dictated by some Machiavellian assholes. And it’s not their fault that every time this government goes to war it’s over resources or over strategic positioning. It’s never over this concern with democracy. So that was a great experience for me, just spending time with those soldiers.

But you know, I did a movie long ago where I played a doctor, and it’s an amazing profession. You get to go in and watch them do brain surgery. Like, I’m watching brain surgery close up. I realized it’s a lot more like construction. They’re hammering away, trying to get the top part of the skull off. Ah, it was wild. It’s a great job to hang out and meet people you wouldn’t meet otherwise.

How did Hunger Games come about? Well, that was an instance of wanting to work with Gary Ross. He’s a phenomenal director.

I hadn’t read the book. People were saying, “Dude, it’s a great book.” Then I read the script, which he co-wrote. [I thought] “Yeah, it’s a pretty good script,” but I didn’t immediately latch on to how good a part Haymitch was. So I turned it down. [Laughs] I figured, that’s that. It’s probably going to be a cool movie. Oh, well. And then a couple weeks later, I get a call from Gary: “Woody, you got to do this. I don’t have a second choice for this part.” We talked for a while. Have you ever met him?

Yes. I mean, what a charismatic dude. So interesting. So brilliant. The mind he has, it boggles. So at the end of it, I was like, “All right, dude. Fuck it. Let’s do it.” And now I’m super-glad I did it.

You worked with Liam Hemsworth and Jennifer Lawrence on that film and Jesse Eisenberg and Emma Stone in Zombieland. Do they ever ask you for advice? None of them really asked me for advice nor do I feel like I’m one to dispense it.

Although I did get a call one time from Emma, who had some shit going on with the paparazzi. I let her know that this is the worst part of the business. The only thing you can do is just not respond. They try and provoke you, because it’s not interesting to just have someone, you know, walking, especially if they have a hat on, getting in a car, that won’t make the news. But if they piss you off, that will make the news. It’s the worst part of this job, but the good far outweighs the bad. It’s a drop in the bucket, although some nights it feels like it’s a big part of it. [Laughs]

“I don’t know how to be unconditionally loving. We judge. It’s so hard not to judge. I remember Gandhi being quoted as having said that he hasn’t hated any man for twenty-five years. I thought, ‘Wow. Wow!’ I just think of some corrupt judges I’ve seen do the most corrupt shit in court. I hate them. I can’t imagine what’s going to turn me around.”

The business has changed over the years, but where do you see it going? There was a recent article about how young people are looking for more and more free alternatives online, so they won’t be paying for cable in the future. I see a lot of that, and it’s just going to keep growing. There’s just going to be more and more people accessing movies online, the same way they get all their music now online. On the other hand, I don’t know that you’ll ever completely replace the theatre experience. It’s a good vibe to sit in a movie, arm to arm, with a bunch of people.

[Just then, we are interrupted by his assistant, Ryan, who wants to know if we need anything. Woody notices his Alamo T-shirt, from the famous Alamo Drafthouse in Austin, Texas.] That’s such a good idea to have cinema where you can have beer and have your dinner. Why not make it almost like sitting down in your living room, but with a great screen and a bunch of people who are psyched to see the movie? That’s also the way that things might head, where they start to shift from the way the theatre environment is a little bit. Maybe have some laundromat there, too — get your laundry going [laughs] while you’re at the movies.

You’re on to something. [Laughs] Let’s get that going! Theatremat, you could call it. [Laughs] Got to have a bar…the drunker they are, the more they’re going to appreciate it. [Laughs] That is also true in theatre, you know.

You come across as being a spiritual person. Is there anything you want to do within this medium where you could channel your spirituality into your work? Yeah, I would like to. I don’t really know what the context would be, but if a film is about the heart, then I think it’s about the spirit, too. Because really to be spiritual is to be loving.

Unconditionally? Well, I don’t know. I don’t know how to be unconditionally loving. We judge. It’s so hard to not judge. I remember Gandhi being quoted as having said that he hasn’t hated any man for twenty-five years. I thought, “Wow. Wow!” I just think of some corrupt judges I’ve seen do the most corrupt shit in court. I hate them. I can’t imagine what’s going to turn me around. Judges, lawyers, politicians, who are typically lawyers first. Judges are typically lawyers first, too. There’s some people who I can’t imagine not despising at the least, hating at the most. I look at the politicians in our country. I know they’re just puppets.

I watched a lot of the Republican debate the other night, and there wasn’t one person on that frigging stage who I’d want to come meet my family. Not one except Ron Paul. He was the only guy that was saying anything real. One of the questions from one of these people at the Heritage Foundation, which is a wonderful little foundation, think tank, asking if Israel decided to nuclear attack Iran would you support it? And they’re all talking about it like, “Well, yeah, yeah, we have to support Israel.” They’re really talking about this shit. They’re really talking about attacking Iran. They’ve put enough fear in people’s heads about Iran and what that would mean if they get nuclear weapons. The countries that have nuclear weapons now are the ones that concern me, particularly this one, because we’re the ones who’ve used it, and continue to use it, with the depleted uranium. We bomb people with it or use it in tanks. And it was only Ron Paul who said, “Absolutely not.” He said Israel can take care of itself because we give them billions of dollars every year to buy our weaponry. In a roundabout way, we support all these weapon industries. But he was the only guy who said, “No, our biggest enemy is the problem with the economy. We don’t need to be putting more money into more wars.” He impressed the shit out of me.

Is there any filmmaker you’re dying to work with and won’t feel complete without their name on your resume? Well, I would like to work with Quentin Tarantino. He’s pretty amazing.

Wasn’t there animosity between you over Natural Born Killers? [Laughs] We did have a thing, we had a little… He knew it and I knew it. I was pretty vocal about, “Fuck him.” And, you know, he let it be known. And it was funny because I remember one time he sat right behind me at some Broadway play. Like, literally I could reach back and touch him. I never said nothing to him. He never said nothing to me. But then, I can’t remember where it was, but it was a couple years ago, and we were at the same deal somewhere in Europe, and I knew he was there, but I had made up my mind that I’d didn’t like the guy one bit. Well, before long, I’m talking to someone, and someone’s tapping me on the shoulder, and then I turn, and it’s him, Quentin Tarantino. [Laughs] And he was so fucking cool. He said, “Look, man, I know we’ve had this shit going on for years — let’s just forget about it and let’s just sweep it under the rug.” We started just rapping, and we had such a great talk. I was like, “This guy’s incredible.” And since then, now we always say hi and chat. We have a very good relationship. But I would love to work with him because he is a tremendous filmmaker. I thought Inglorious Basterds was one of the most amazing things I’d ever seen. So probably him and Fernando Meirelles. Would love to work with that guy.

What about Broadway? Is that still a dream? Well, I did it once, but it wasn’t that satisfying. I didn’t really love my performance. The last major thing I did on stage was Night of the Iguana, Tennessee Williams’ play, in the West End, and that felt like prison.

Why? I imagine prison would be a little bit more satisfactory experience. Terrible. I didn’t like it at all. I didn’t like my performance. I didn’t like the production. I realized the play was flawed. I just allowed myself to believe that there has to be merit to this play. It won the Pulitzer in ’61, I think.

How many weeks were you in it? Months! Six months including rehearsal. So I decided after that, I will never do a serious play. I’ll only do comedies.

Interesting. Why? Yeah, just think about it: it’s so much better to come out at the end of a play, after an hour-and-a-half, everybody’s been laughing. It’s a better vibe than doing some three-hour play, and you come out at the end, after you’ve accomplished everything you’ve supposed to, only to get punched in the goddamn — anyway [laughs], that’s how Night of the Iguana was.

What about more comedic films? You’ve taken some fun roles in Friends with Benefits and Zombieland… I’m open to that. I’d prefer to do comedy. But when you get a script given to you like Rampart, you can’t just not do it. It’s not even an option, because it’s a great script. It’s the director I most like working with. The way that they stack up, it’s like I’m not even in control. I’m just being led the way I’m supposed to be led. I’m more in control of my play production, but even that has to fit into a slot. Nah, I prefer comedy.

You work a lot. Yeah.

Why? I don’t know. Shit, I feel like, I don’t know, surprised, you know?

What would you say are your goals and aspirations going forward? I want to do more writing and directing of plays, and I also have some screenplays that I’ve written — three — I’ve just gotta do rewrites on them, and then I’d like to direct those as well, because they’re all comedies. Every project that I’m working on writing is comedy, because I really would like to get my version of what’s funny out there. A lot of times you’re a pawn, or even a fish if you’re lucky, in someone else’s vision, which is hopefully cool. But I’ve got my own particular brand of humor that, until Bullet for Adolf, I hadn’t really articulated it before, or gotten it out there. So I want to keep doing that. You know, now that I’ve outlasted my looks…

What are you talking about? I think it’s best to move into directing.

Outlasted? Well, either my looks have betrayed me, or I’ve outlasted them.

Woody, what are you talking about?! I’m not saying that to get you to say, “No, you look fine,” it’s just my own perception.

Twenty-five years in the business as an actor, and you’re just going to give it up? Has it been that long? Well, let’s see, I’m fifty. I started working when I was twenty-three, so what is that, twenty-seven years. I feel pretty fucking lucky.

stylist Kendrick Osorio groomer Lona Vigi

cover: pea coat: Edum turtleneck: American Apparel

sweater: Bloomingdales t-shirt: James Perse

t-shirt: James Perse jacket: Nudie Jeans jeans: Nudie Jeans

blazer: Edum shirt: James Perse

pea coat: Edum turtleneck: American Apparel jeans: Nudie Jeans cap: Pic

sweater: Bloomingdales t-shirt: James Perse jeans: Nudie JeansAll organic clothing available at Bloomingdales & American Apparel