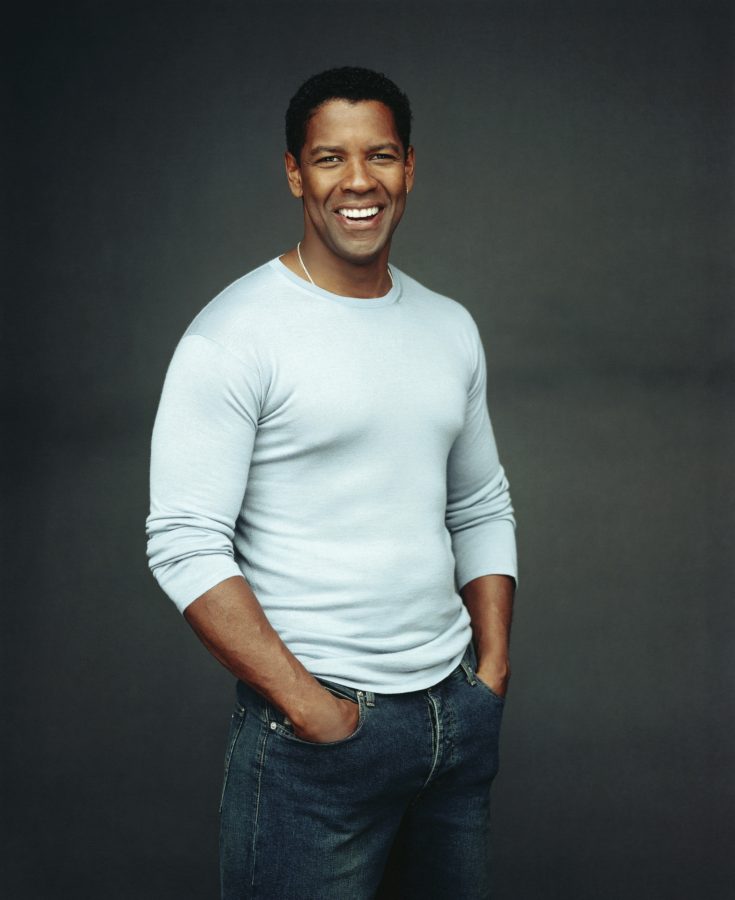

on’t hold your breath waiting for Denzel Washington to turn up on TMZ.com. And you’re clearly off your meds if you think he’ll ever get booked for a DUI on PCH, or make a trampoline out of Oprah’s couch, like a couple of his fellow first-dollar-gross peers did last year. In fact, let’s face it: in certain quarters of the entertainment media, Washington — a doting father of four who has been married to the same woman, Pauletta, for more than twenty years, and only speaks to the press when he has a project to promote — is considered downright dull. (Which is no doubt just the way he likes it.)

on’t hold your breath waiting for Denzel Washington to turn up on TMZ.com. And you’re clearly off your meds if you think he’ll ever get booked for a DUI on PCH, or make a trampoline out of Oprah’s couch, like a couple of his fellow first-dollar-gross peers did last year. In fact, let’s face it: in certain quarters of the entertainment media, Washington — a doting father of four who has been married to the same woman, Pauletta, for more than twenty years, and only speaks to the press when he has a project to promote — is considered downright dull. (Which is no doubt just the way he likes it.)

But there’s nothing dull about what he brings to the space between “Action” and “Cut.” It’s an alchemy of talent and passion that twice has translated into Oscar gold: a 1989 Best Supporting Actor prize for Glory and the 2001 Best Actor award for Training Day. And this year, the Mount Vernon, New York, native is likely to be vying for Oscar honors again — several of them, in fact.

As an actor, he’s a good bet to be nominated for his work as a charismatic 1970s Harlem drug kingpin pursued by Russell Crowe’s dogged cop in American Gangster. He could also be considered for his performance as Melvin B. Tolson, the inspirational teacher who took a group of students at Wiley College, a small black school in eastern Texas, and molded them into a team of fire-breathing orators who emerged from the Jim Crow South of 1935 to defeat the reigning national championship debating squad in The Great Debaters.

For the latter, his second feature film as a director, he is also a potential candidate for a directing nod, and if it winds up in the Best Picture running (a possibility, based on the glowing reviews), Washington will be eligible for yet another Oscar because he — along with, among others, Oprah Winfrey — is one of The Great Debaters‘ producers.

In The Great Debaters, as with many of his films, Washington invested a fact-based story with heart and emotion. And just as he guided Derek Luke and Joy Bryant to breakthrough performances in his directorial debut, Antwone Fisher, The Great Debaters has introduced talented newcomers Denzel Whitaker, Nate Parker, Jurnee Smollett and Jermaine Williams.

The transition to directing came swiftly and smoothly for Washington, an intense performer who is never the life of the party on a movie set because he is so focused on his character. Although some were surprised at how naturally he took to the move behind the camera, Tony Scott is not.

“He has always been a handful, but that’s because he’s so dedicated to what he does,” says Scott, who directed Washington in Crimson Tide, Man on Fire and Déjá Vu and is currently working with him on a remake of the 1974 action drama The Taking of Pelham 123. “Whether you’re directing, acting or painting, it really comes down to the choices you make in the moment. Denzel does that so well with words on a page. His taste and choices are just impeccable.”

Washington says his move into directing is a way to soften the blow when directors like Tony Scott and his brother Ridley, who directed him in American Gangster, inevitably stop calling. But it also fits the priorities of his personal life, which revolves around his wife and kids.

He rarely makes a film that isn’t a short plane ride from home. And after being a regular in the stands as his son, John David Washington, developed into a standout running back in high school and college, Washington now attends St. Louis Rams games as John David tries to work his way from the practice squad to the roster. After growing up as the son of a Pentecostal preacher who rarely showed affection, Washington dotes on his children with unabashed enthusiasm. It’s easy to imagine him as a patient, mentoring presence with the young casts that have anchored his first two directing efforts.

But even with his commitment to family and move into the director’s chair, Washington hasn’t lost any momentum onscreen. Indeed, his work in The Great Debaters is as dynamic and uplifting as his portrayal of drug lord Frank Lucas in American Gangster is ferociously nuanced. Both echo the power of his Oscar-winning turns in Glory and Training Day, and his nominated performances in Cry Freedom, Malcolm X and The Hurricane.

“What Frank Lucas did was so terrible to his community, and to the United States, that my brother’s greatest challenge was finding an empathetic character based on what was in the script,” says Tony Scott. “The only way you got to that place of empathy was through Denzel.”

When Ridley Scott revived American Gangster after Universal scrapped a version that was to re-team Washington with his Training Day director Antoine Fuqua, Scott wasn’t sure the star would stay with the project. But the actor was his first call, and Washington’s willingness to remain aboard saved the film.

“This is going to sound a bit rough on the rest of the community, but in my mind there was no one else on his level,” says Ridley. “Denzel is so in his time right now. He is an actor at the peak of his powers.”

And based on the reception given The Great Debaters — which has been heaped with critical praise and honored with several end-of-year awards — his directing chops aren’t too shabby, either.

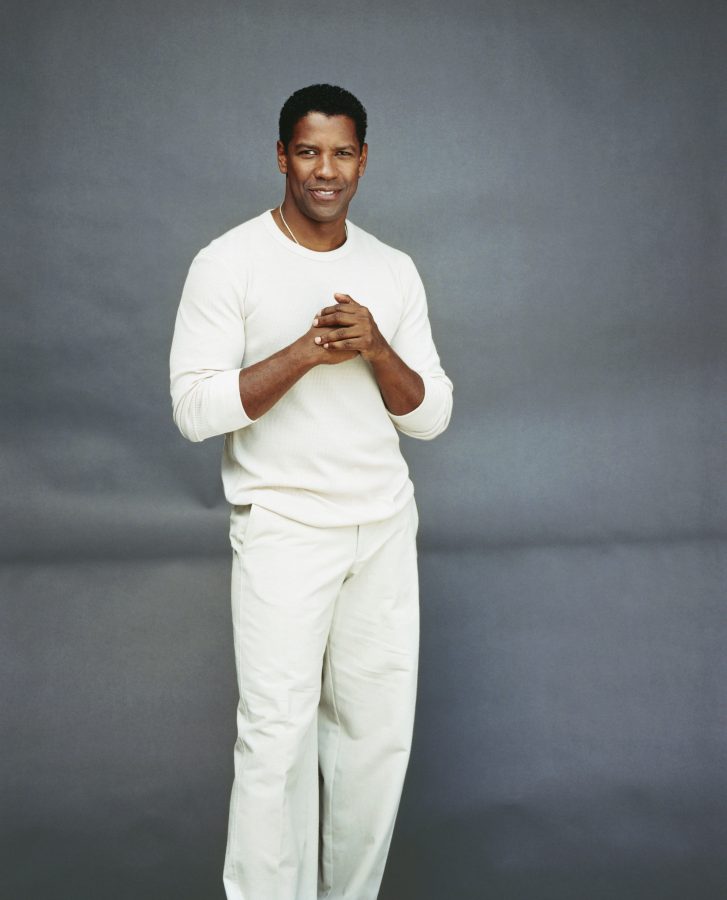

Washington, who is always amiable, albeit guarded, when doing interviews, was in an especially good mood when he spoke to Fade In.He had just taken a break from the editing room to show a cut of The Great Debaters for an episode of Oprah devoted to the film, and had been reunited with his young cast members.

![]() t’s a very strange time in the entertainment business. We have one union currently on strike — the writers — and possible strikes by the actors forthcoming as well. Is there a way that talent can change the current landscape when large, diversified conglomerates have more power than ever and dwarf the three unions? The bottom line is, they’ve got to figure out a way to chop up these new revenue streams. How do you crack ’em, when it’s hard enough to get your money just from regular box office? I know that it’s complicated, and there’s no simple answer. They’ve got to get in there and hash it out and figure it out. It’s no good for the business to shut things down, but I understand that people have got to do what they’ve got to do to get their fair shake.

t’s a very strange time in the entertainment business. We have one union currently on strike — the writers — and possible strikes by the actors forthcoming as well. Is there a way that talent can change the current landscape when large, diversified conglomerates have more power than ever and dwarf the three unions? The bottom line is, they’ve got to figure out a way to chop up these new revenue streams. How do you crack ’em, when it’s hard enough to get your money just from regular box office? I know that it’s complicated, and there’s no simple answer. They’ve got to get in there and hash it out and figure it out. It’s no good for the business to shut things down, but I understand that people have got to do what they’ve got to do to get their fair shake.

Now that audiences can download films from the Internet via iTunes, etc., what impact — if any — will this new technology have on the way films are made today? The traditional business is still good. 2006 was one of the biggest years for film. The more interactive we become — and I don’t think we really have become interactive yet — the movies will be able to draw power from the Internet. People still love that communal experience: going to the theatre, sharing popcorn, laughing and screaming together. There is all the more need to do things together.

When you say it’s not that interactive, how do you see this communal feeling evolving as more people get entertainment from their computer? Who knows for sure? But it’s telling that more people went to the movies last year than [almost] ever before, and the movies made more money than [almost] ever before. So it’s not dying the way people said it might. It’s like what’s going on right now with the writers’ strike. People are saying, “How do you slice up that pie?” Who knows? This stuff is complicated. I tell my own kids, “Don’t steal music. Pay the 99 cents per song, do it right.” There is room for both.

How do you feel the business has changed with respect to increased opportunities for African-American actors, since that historic night that you and Halle Berry won Oscars? It’s a process. I never thought one night would change everything. In this business, things change when a movie makes 100 million bucks. There have been African-American actors who’ve won the Oscar, but weren’t big box office. Box office rules the day.

If The Great Debaters does a ton of box office, there might be ten movies about debaters next year. We all want the big movie, and that changes things more than anything else. I remember winning [the Best Actor Oscar] for Training Day, and I was in the gym the next day, and a young African-American guy came up to me and said it was great. I said, “Thanks, it’s all good.” He said, “No, you don’t realize how many people you’ve inspired, and who might be following behind you.” Maybe in that regard it helps young actors to keep fighting and doing good work.

“A part of doing what I’m doing behind the camera is because I understand that eventually, the phone will stop ringing. Now, it isn’t just to extend my career, but also because I’m interested in [directing], I’ve got a passion for it.”

“They’ve got to figure out a way to chop up these new revenue streams. How do you crack ’em, when it’s hard enough to get your money just from regular box office? I know that it’s complicated, and there’s no simple answer. They’ve got to get in there and hash it out and figure it out. It’s no good for the business to shut things down, but I understand that people have got to do what they’ve got to do to get their fair shake.”

Will Smith has been very active in barnstorming his pictures around the world, with the idea of helping erase that stigma that African-American stars don’t play well overseas. Have you found a stigma, and have you found that being in those countries has helped you build audiences there? I find I play better and better overseas, but you need to barnstorm. You do need to go and promote. It’s hardest on comedies. The jokes don’t translate all the time. I’ve had great success overseas, and I guess that is a change, or plus, in the Internet world we live in. It’s a smaller world, one global market. It also depends on the movie. Certain movies just don’t translate overseas. American Gangster just opened huge in England, France, all over the place. The Bone Collector did great business overseas. To Will’s credit, he has helped by barnstorming. Going to India for two weeks, and promoting, [is] important.

Tyler Perry has bankrolled his own comedies and scored hit after hit that he owns. Well, he’s been at it a long time, in the theatre, and he slowly built a following. But like I said, had his movie done $1 million in box office, no one would be talking about Tyler Perry. His movies have done great business, and Hollywood has jumped on that because he can make them money.

He’s gotten to the place where he puts up money and owns his own films. Have you considered doing that? I don’t have that kind of money. Maybe he’s doing better than me. It depends upon the formula. He came to it one way, and I’ve come to where I am now as a filmmaker from a studio-oriented, traditional way. I’m all for what he’s doing, but I like my course. There’s no “one way” of doing it.

The midbudget drama, a staple of your acting resume, is disappearing in favor of big-budget films and low-budget films. Why do you think this is happening? I was reading some articles on the newspaper business. When a company goes public, they look for fifteen to twenty percent return, every year. But for privately owned newspapers, five percent is considered good. In the days of privately owned studios, five percent, or maybe it’s higher than that, was considered good. Now, there’s such a bottom-line, repay-the-shareholder mentality that there is more pressure put on the performance of the films. But at the same time, sometimes those midrange films become the biggest hits. At the end of last summer, one of the best performers was this film Superbad, the one that starred Jonah Hill [and Michael Cera].

Big, big hit. Just because you spend $200 million and have big stars doesn’t guarantee anything. Companies could turn around and say, “We’re going to do midrange dramas. We’re not going to do high budgets.” Maybe they lose out. People will want what they want, and you can’t just boil it down to any particular formula. I’m looking at the success of American Gangster, and I can’t believe it.

Why? Maybe it’s timing, but I’ve never had a film where I heard from so many people in the streets that they just couldn’t wait to see it. This was before it came out. Maybe they were hungry for a gangster movie; maybe it was the combination of Ridley [Scott], Russell [Crowe] and myself. For whatever reason, to make an R-rated drama about a Harlem heroin dealer, and make it for $100 million, I’d think that was a gamble. But it’s paying off, so go figure.

American Gangster‘s popularity brings to mind Scarface. Adults might have a tough time explaining how that character became such a favorite for a young audience. I’ve thought the same thing. A young girl from MTV was interviewing me, and I had to ask her, “What is it that young people like about these criminals?”

She said, “You’ve got to understand. Here is a person who stands up against authority.” A lot of young people are sick of what they’re seeing in this country, from our so-called leaders. This is like organized crime anyway. A lot of them are upset. Beyond that, you’re in your nine-to-five job, a world where you may not have power. And here is this guy who thumbs his nose at authority and he’s willing to take chances. And, yes, he pays the price, but maybe you get to live out a fantasy by going to see this movie, though hopefully you don’t come out of it wanting to become Scarface. That has been around forever. I loved White Heat, those Bogart and Cagney movies…Angels With Dirty Faces. I grew up on those films. There is something about that tough guy who doesn’t play by the rules. There’s probably some book somewhere that a psychologist has written that explains why.

Your mom grew up in Harlem and observed its decline due to drugs and crime. How much concern did you have about being too sympathetic to a man who killed and became a huge drug dealer whose product decimated a community? To be honest, I was surprised so many people considered him to be a sympathetic character. Here was a guy who was shown going out, shooting people in the head, going back and sitting down and having breakfast. And yet, people found him sympathetic. I guess that made him interesting. But it was important for me for the audience to know that, although he went to jail and gave up a lot of people in order to save his own neck, he came out of jail broke and alone. There was a price to be paid. I didn’t think ahead of time, nor did I try to make him sympathetic. But I found it interesting when people would say, “Well, he’s not such a bad guy,” and I’d respond, “What, are you kidding? This guy was crazy! He’s killing millions of people with heroin, he’s shooting people.” [They’d say,] “But he’s a nice guy. Misunderstood. He gave out turkeys to the community.”

Did you come to respect or admire Frank Lucas in any way, despite his career choice? What was it like, sitting down with him for the first time? I told Frank right away, from the start, “Look, I’m not here to praise you, to win awards, any of that kind of stuff. You did some terrible things in your life, and you paid the price for it. That’s the story I’m interested in telling.” He paid the price, in terms of jail, and even in his physical body. He’s had a lot of issues, physically. He’s hurt by what he’d done. This was how he was raised; it was what he knew. He said, “Denzel, I never went to school, I’d have been a janitor.” Graduate school for him was fifteen years with the most notorious gangster that ever lived in Harlem. That was his teacher, his mentor. That was the arc of his life. He saw his twelve-year-old cousin murdered when he was six; he was stealing chickens and pigs as a little kid. He moved up to the point where, at fifteen or sixteen, he had to get out of North Carolina. So he goes to Harlem and picks up where he left off. Who does he meet? The biggest gangster in Harlem, and he becomes his bodyguard, hitman, or whatever he did for him, and that was his education. I’ve never heard him say, “Bumpy Johnson.” It was, “Mr. Johnson taught me this. Mr. Johnson taught me that.” It goes back to education, opportunity and how every child is important. Because once that child gets lost and [starts] going in another direction… Frank Lucas is, in a way, a very brilliant man. He’s no dummy. He’s not an educated man, but not a dummy. What would have happened if he hadn’t grown up so poor, and he’d gotten a good education?

If, if, if. It didn’t go that way. He said, “I quit the business, went back to North Carolina. I sat there two or three weeks, twiddling my thumbs,” and he couldn’t do it. He knew he was going to get caught and did it anyway. He was like that boxer who won’t retire.

You’ve described your approach to work as chopping wood, and you’ve always had a working-class ethic. How tough is it, then, to process the fact that you got paid twice to do American Gangster, since you were pay-or-play the first time it fell apart? Well, one-and-one-half times.

We cut our fee the second go-around. The bottom line is, with a pay-or-play [deal], you take yourself off the market and turn down the other jobs. So if that studio decides not to make the movie, after you’ve turned down those other jobs, that’s the deal with that. And if I’d taken another film during the period that American Gangster was supposed to be shooting originally, then that money [would have gone] to Universal. It’s not like you can go in, sabotage a movie, and they shut it down, and you get paid and do another movie. You can’t double dip.

Are you saying they bought a period of time in your life? Exactly. I forgot how long a period it was, but it was at least the four months that we were going to shoot the movie. But really even more, because there are two or three months to prepare. You take yourself off the market. I’m going to do a film in February with Tony Scott. If that were to shut down…I’d have three or four other movies that were going to shoot at the same time.

Antoine Fuqua was set to direct American Gangster originally. What was your reaction when Universal pulled the plug so close to production starting? On one hand, there were just things about that movie that weren’t coming together, that weren’t fitting right. On the other hand, I was shocked they fired the director without even telling me ahead of time. I was shocked. [The production] wasn’t coming together, smoothly. It was trouble. So I walked away from it for whatever it was, two years or so.

How did it revive? My agent [Ed Limato] called me. At one point, [director] Terry George and Don Cheadle were going to do it; they were talking to this one and that one, and I’d forgotten about it, to be honest with you. Then my agent called at the beginning of last year, and said, “What do you think about Ridley Scott?” Ridley Scott? Are you serious? He said, “Yeah, Ridley Scott and Russell Crowe.” I was like, “Whoa. Maybe I should sit down and see.” Once I sat down with [Ridley], first thing I did was call Antoine. I said, “I just want you to be the first to know.”

How did he take it? He was cool. Luckily, he’s moved on and is doing other things.

How different was the film you made from the one you were planning to make? Who knows? We didn’t make the other one.

You used that time slot to do Julius Caesar on Broadway. Bad reviews for Denzel Washington are as hard to find as hen’s teeth. How did you feel when critics didn’t spark to that production? Well, I don’t read reviews, at all. I don’t read them when they’re good and I don’t read them when they’re bad. For what? They hail you and then they nail you.

Was there an experience that prompted you to do that? No, I just learned over time: What’s the point? It really doesn’t have anything to do with what I do. I enjoyed the experience, and we were sold out. A lot of [theatre critics] sharpen their pencils for anyone coming from Hollywood. I heard one of the things they ripped was the audience. Well, it’s just a moviegoing audience. I’m like, “Whatever. It’s all good, all good. Sold out. Great experience.” And I will do it again. I’m looking to go back to Broadway. So critics, be ready!

Anything in particular you’re looking to do? I want to do more Shakespeare…or maybe an American play. Who’s that great playwright who did Long Day’s Journey Into Night? I’d love to do something by Eugene O’Neill, [though] maybe not that play. I started in the theatre, and O’Neill was the first [play] I ever did: The Emperor Jones. The second one I did was Othello. I love Shakespeare because it’s a great challenge. And I love the theatre because that’s where I’m from.

Having played six fact-based people onscreen, what is it about roles based on real people that you find so attractive? Nothing, really. They just happened to be good stories. The fact they were real people had nothing to do with it. Richard Attenborough comes to me and says, “I want you to play Steve Biko in Cry Freedom,” I say, “Uh, OK.” Malcolm X was a role I couldn’t resist, and Rubin “Hurricane” Carter was another one I couldn’t resist. Remember the Titans wasn’t so much about the real guy, but a great story — even though he’s a great guy, Herman Boone. So it wasn’t as much [about] wanting to do a biography. First of all, I wanted to play a football coach. I was living out the fantasy of a frustrated coach, a Monday-morning coach. The fact it was a true story was icing on the cake, but it was a good story.

After watching Malcolm X and later Hurricaneget undermined by people questioning disparities between the film and what really happened to Hurricane Carter, how much do you worry about that being used to try and undermine American Gangster or even your new film, The Great Debaters? On this film I directed [Great Debaters], I say, right from the start, “Inspired by. Loosely based on.” American Gangster, same thing. It’s not a documentary. There is no eighty-seven-piece orchestra that walked around with the real people, playing a score while he’s shooting people in the head, or doing whatever they do. This is loosely based on real events. Harvard University wasn’t even the national champ [as is depicted in Debaters]. USC was the national champion. So they actually beat the University of Southern California in 1935. We changed it to Harvard because Harvard was the academic standard. Someone will probably come out of the woodwork, saying, “Well, it wasn’t Harvard.” Well, Harvard wasn’t good enough that year. It’s so easy to jump on that bandwagon, but it’s not a documentary, and it never claimed to be.

How much truth do those movies owe? It depends. In the case of The Hurricane, that generated the most controversy because there were lives involved: family members connected with people who were killed. [Debaters] was about a little school that won a debate. Bottom line is, they did win against the national champions. If that was Harvard or Yale or University of Oshkosh, they won. Hurricane was different. The question was: Did this man kill these people? Well, when you’ve got the family of the people who were killed, that’s a whole different deal.

How does American Gangster factor into that discussion? Well, [with] American Gangster, yeah, we’re loose with the actual facts. Actually, who knows? Who was there? Half the people who were there are dead. Probably a lot of them weren’t innocents. They’re all dirty. I met a guy in Harlem who said, “Because of Frank, I had to jump out of a car at fifty miles an hour. Frank was crazy. He was going to kill me. You ask him.” So I asked him. He said, “Yeah, the guy jumped out of the car.” “He said you were going to kill him.” “No, we wasn’t going to kill him. And did he tell you he owed us about $50,000, and that he stole our dope? No, he must have forgotten that part.” So, you know, whose truth is it?

How did the story of The Great Debaters come to you? My agents knew I was looking for things to direct. Maybe four years ago, they came to me with it. I read it. I was very moved, got to the end and thought it was powerful, interesting and true. From there it was a process of working on it, going off and doing another movie, coming back and working until we were ready.

You read a lot of scripts. Does it have to be love at first sight for you to direct? There were great roles for you in Antwone Fisher and The Great Debaters. What made those films different from the many films you act in? Actually, in both of those films, I’d never considered them for acting, never looked at them from just an acting standpoint. In both films, I’m acting in the movie because, in order to get the money to make the movie, I had to act in it. In fact, in The Great Debaters I figured, well, if it’s good for business for me to act in the picture, I’ll play [Wiley College president James] Farmer, and I’ll find someone to play Tolson.

I talked to William Morris about that. They said, “Well, if you’re not going to play the lead, you’re only going to be able to spend this amount of money.” We [couldn’t] make the movie for that, not the way we needed to make it. It definitely wasn’t because I wanted to play Tolson, and in fact, I don’t think I’m bad casting for the part. I know how to talk, and I’ve played the coach role before. I can give those speeches, and fire up the troops. But I did not look at it from the start as an acting vehicle at all.

“They didn’t call me on The Matrix. I didn’t get a call on Lord of the Rings, or Harry Potter… Why do you think that is? [Laughs] I’ll tell you what would have been more in my wheelhouse, and [Matt Damon] done a great job, obviously: the Bourne series… I haven’t been asked to do any [comedies]. I’d like to put it right out there, please: Hire Denzel to do comedy.”

There is a haunting scene in the film, where the debate team stumbles upon a lynching. You decided to show less than you could have. Why? I’ve learned a lot from the great directors I’ve been fortunate to work with. I went over to New Zealand about a year ago, and did some work with Peter Jackson on another project I might direct. It’s just a short two-minute film we shot about an American tank group in WWII, Brothers in Arms. He was saying, “You don’t show the monster too much.” It’s like the shark in Jaws.

The less we showed the hanging man, the more terrifying it is. You don’t want to give them too much of it. I’ve already cut some of it, and there wasn’t that much onscreen in the first place. But it’s fear of what’s going to happen. That’s why I liked running the car [with the debaters and their coach] right up into it. Everything stops. You can extend time. You really do feel the tension. You’ve got the kid in the car with the knife who wants to cut him down, the changing of the gears in the car, and the kids in the back, and everything is sitting still. Then boom, that scene is off to the races as they struggle to get away from that mob.

An African-American professor recently found a noose hung over her door. How much has the world really changed? Is racism really that close to the surface? Obviously, it’s not a distant memory. It was a different time, but that way of thinking never completely goes away. It’s the human condition. No amount of legislation gets rid of it. It’s a small percentage, a minority that might do something like this, but there is a ripple effect. The fact that it’s big news now, in a sense, shows how it has changed for the better. It’s big news now because it’s so rare. It probably wouldn’t have been considered news then. It wouldn’t have made CNN in 1935.

When you want to make a period movie about racism, and your three leads are unknowns, how receptive are financiers? What were their concerns, and how did you convince them? Did you make any concessions? Again, that’s why I ended up in it. They said, “Fine, you want three unknown kids, 1935?” I don’t mind being in it, if it can help bring in people to watch these young kids. They’re very, very good.

Once you agreed, then, did that get you the money you needed? That’s a tricky thing, too. I didn’t want to put too much pressure on the film by spending too much money, either. Just finding the right balance was important. Our budget ended up around $25 million, which is small by today’s standards. But it’s still a lot of money, and I give Harvey Weinstein credit for putting up that money, for going for it and believing in the product.

Both films you’ve directed, and the one you’ll direct next (Brothers in Arms), are about African-American characters. You’ve said that sustaining the momentum of the historic night you and Halle Berry won Oscars depends on creating opportunities for African-American actors to be discovered and shine. The films you’ve directed are built to showcase newcomers. How much of a factor is this in the projects you choose as a director? It hasn’t been a conscious factor, and it wasn’t why I chose to do this film. It wasn’t why I chose Antwone Fisher, because I didn’t know I was going to choose an unknown actor. But it has worked out well for Derek Luke, who is doing great work. I can’t honestly say I’m doing this because it allows me to bring along some young actors. Yes, it does give opportunities to young African-American actors, and I’m happy about that. But Forest [Whitaker] and I were too old to play students. Those days are over for us.

Did you not have a feeling of pride when you watched Derek Luke in Friday Night Lights or one of his other films? Yeah, and this is what I’m saying. It’s wonderful. He can deliver.

And these young kids [in The Great Debaters] delivered. This little kid Denzel Whitaker, Jurnee Smollett, Nate Parker and Jermaine Williams, they are really committed to this. I set them up in a debating camp; they went to Texas Southern, learned how to debate and debated against that school’s freshman team. I just came from doing Oprah’s show, and watching them, their excitement, as they were all dressed up. You get older, or should I say wiser, and maybe a bit more cynical. But to look at these kids and that excitement really takes me back, and I get a real charge out of that. My career as a director is not just going to be based on discovering new talent. But why not?

What’s the hardest part of directing a picture you also appear in? Directing a picture that I appear in on camera? [Laughs] I had to make a decision at the beginning. That is, “You’re in it. Embrace it. Go for it. Don’t take a negative approach.” Even in the first film I directed, I found myself more of a reluctant actor because of the way I work as an actor, which involves a lot of concentrating. You just don’t have that opportunity as a director. You’ve got 1,000 people, asking 1,000 questions and they need 1,000 answers every day. There is just no time to work on your character. What I’ve learned from the first experience, and going into this one, is that, in working on the film, and preparing to direct that film, I play all the parts anyway. I read them all, out loud. I sit there, with the writer, reading them to see what works, what doesn’t work. So I was preparing for the role all along, in a way.

What did you do better as a director on Debaters vs. your first film, Antwone Fisher? Preparation. Knowing what to prepare for. It was a terrifying experience, going into the unknown at this point in my life. I loved it now, but I knew what to expect this time. Tech scout? I know what that is. First time, I was told, “We’re going on a tech scout,” and I’d say, “Well, what is that?” Or, like that first time, when you’ve got to talk everybody through your whole idea of the movie. I said, “The whole movie? I don’t have any ideas. Or any good ones.” It’s just knowing a bit more about it; where not to waste energy, where to best spend your energy, pacing yourself. Getting there early. Spending the weekends, looking at the next week’s work. Visiting your locations. Figuring out your shots. Working with the storyboard artist. There’s a whole process.

How much of a goal is it to get to a point, like Mel Gibson did in The Passion of the Christ and Apocalypto make the other one where you can just be the director? That’s my goal, and hopefully that will be the case next time.

What motivated you to take on directing in the first place? Is there a model of success you’ve used to guide your directing career? I don’t think it was any one thing. I guess I was just ready. There comes a time when I feel like more stimulation, doing something new, taking new chances. The most terrifying, and ultimately satisfying, thing I did was direct Antwone Fisher. And feeling like I have a new energy, a new passion — a new career, really. I look at guys like Mel, Warren Beatty, Clint Eastwood. You just feel the need to expand. There is that element of control. The canvas really does belong to the director, ultimately. You make movies, you act in them, you do your part and you leave. You think you did this great ten-minute soliloquy, and the whole time they’re doing a close shot of a bottle of water or something. It’s a director’s medium. It’s not that I needed to control things. It’s more about the collaboration. I found I enjoy working with production designers, working with actors and writers. The days aren’t long enough.

Do you ever imagine yourself giving up acting entirely for a life behind the camera? I don’t know. I’ll tell you what. Directing has made me appreciate directors much more. It’s hard work, and it’s not like you can crank out a picture each year to direct. It takes too much time and energy, and time away from home, all those things. I don’t think I’ll stop acting anytime soon. But there does come a time when you’re no longer the leading man. I guess, though, if you’re the director, you can hire yourself.

So this was part of your shift toward directing? A part of doing what I’m doing behind the camera is because I understand that eventually, the phone will stop ringing. Now, it isn’t just to extend my career, but also because I’m interested in it, I’ve got a passion for it. I go back and look at Clint Eastwood. He’s in his seventies, and making great movies like Mystic River. I’m like, “Man, that’s my hero.” I don’t want to be sitting around at seventy years old going, “Wow, why doesn’t anyone call me?” I want to be involved. I like what I’m doing. I love directing, the whole process. I love interacting with all the different departments. I’m the happiest man on campus, because at fifty-two years old, I’ve found a new career. I guess I found it in my forties, but you understand.

Some looked at ICM’s attempt last year to put your agent, Ed Limato, out to pasture as ageism. How much of a concern is that to an actor as you get older? How much harder is it for actresses? Start directing. I’m not waiting. It’s got to happen eventually; that’s the nature of the beast. The business allows men to hang on longer than women. They kick them to the curb at thirty-five.

You were the biggest movie star repped by ICM. How involved did you get in that skirmish with Limato, and did the upheaval leave you in a hard position? No. To this day, I’ve never heard from anyone else from ICM, before this whole thing happened, or since. That told me everything I needed to know about that. And I’ll leave it at that. Not a thank you, not a “We’ve got a tough situation,” not anything. That’s the way they do business, I guess.

You’re going to star in The Taking of Pelham 123, your second remake after Manchurian Candidate. Why do another remake? It’s a good story. We’re a little older, but if I [mentioned] Taking of Pelham 123 to my kids, they don’t know the movie at all. That was thirty years ago. They don’t have a clue what it is. Tony Scott has a unique take on it, and they just as easily could have changed the title. The basic premise is there, but I don’t know if they’ll use the title. The remake part is the least of it. I just think it’s a good story, and needless to say I like working with Tony. I look forward to working in it with John Travolta. That will be fun.

Was the original a favorite? I’ve never seen the original. Never have. There might be those who compare, but the overwhelming majority of the moviegoing public probably never saw the original, at least not in a theatre.

The original Manchurian Candidate was so edgy that Sinatra put it on the shelf after JFK was killed and kept it there for years. How much did the lack of a Cold War take away the urgency of the brainwashing themes in the remake? That could very well have mattered. But we were definitely a more innocent society back then. Now, death, destruction, manipulation and all those things [are] nothing new. You can catch that on the news or on a cartoon. It was a more innocent time, and the threat of the Cold War over our heads was a propellant for that film.

Why have you done so very few comedies? I haven’t really been asked to do any. I’d like to put it right out there, please: Hire Denzel to do comedy.

You’ve not been in a sequel. Has there been a popcorn summer film that came your way that you decided wasn’t for you? No, not really. They’ve been going back and forth with a script for another Inside Man, but I just didn’t think the material was quite there, yet. They didn’t call me on The Matrix. I didn’t get a call on Lord of the Rings, or Harry Potter. I don’t know why. Why do you think that is? [Laughs] I’ll tell you what would have been more in my wheelhouse, and [Matt Damon’s] done a great job, obviously: the Bourne series. I’m sure any actor like myself, who’s done more dramas, would have liked to be in that. If you’re going to do a tentpole or sequel deal, that would have been a good one to do. I give Damon a lot of credit.

When choosing projects, what elements must be present in the script? What elements would you consider a dealbreaker? It starts with reading something you like. I don’t have a list of elements that has to be there or can’t be there. It’s not that deep. Where I am at this point in my life, I’m not looking to play the most notorious drug dealer in Canada. I don’t think I’d do that right now, or another debating film. I like changing it up, reading a lot of stuff and responding to whatever I respond to. I do get more biography films, probably, than any actor in America. Ninety-nine percent of them I turn down, because people think that’s all I want to do. I’m not interested in that at all.

Is there a historical figure you do want to play? Thelonious Monk. I love Straight, No Chaser, [the] documentary — that world. That guy is one I’d like to do.

Are you going to direct a Sammy Davis Jr. film based on the book In Black and White? It’s a book that Brian Grazer bought and is developing. I don’t know if I will or not. I am not set to direct it, to set the record straight.

You’re being promoted for Oscar consideration in the Best Actor category for The Great Debaters. That puts you against yourself in American Gangster. How does this get decided? Harvey’s going for it, and Universal’s going for it. I guess I might cancel myself out, I don’t know. To be considered is enough for me. It’s great, but the biggest thing is to make this the best film I can, and then see how it all plays out.

Your performance in Philadelphia didn’t get nominated because you submitted for Best Actor and got eclipsed by winner Tom Hanks. Why won’t you put yourself in the Supporting Actor category? Well, remember, I won the first time for Best Supporting Actor in Glory and got nominated another time for Cry Freedom. There is no difference. It’s like saying you won the Pulitzer Prize for a 1,500-word article or a 3,000-word article. It’s just about the amount of lines I have as an actor. They’re equal. One is called lead. Does somebody do a line count? I don’t know.

Which would mean more to you: winning another Oscar or watching your son crack the starting lineup of the Rams and break loose with a long touchdown run? Well, you know the answer to that.

How has that been, a former football player like yourself, helping your son accomplish what he has? It has been a thrill watching them all. It has gone by so fast. My daughter, she’s a sophomore now; she’s going to one of the Ivy League schools. I’m so proud of her. My twins are thriving, unbelievably, as they are going on seventeen. [I’m] watching them grow up and leave us, basically. We were in San Francisco at my son’s game just yesterday. It’s a real thrill. That’s the greatest production I’ve been involved in: my wife and I and these four kids. My greatest directing job — though here, I’d just be assistant director. Definitely not the director, but the AD. Hopefully, the first AD.

With two actors as parents, are any of the kids planning to follow suit? My youngest daughter is. My oldest son, the football player, and my older daughter have been sniffing around script development. My son, he reads scripts; I give them to him, and I listen to him. He’s the one who talked me into doing Training Day and American Gangster. I was really going back and forth, and he said, “No, Dad, you’ve got to do this.” They are all movie buffs. They read and they have a good eye. My daughter interned this summer for Jerry Bruckheimer. I don’t push, and I don’t think any of them but my youngest daughter is interested in being in front of the camera. But I would love to be in business with my kids. That would be great.

We are coming up on a political year. Reports said your endorsement helped unseat the longtime mayor of Mount Vernon, where you grew up. Why did you get involved there, and will you get involved on a national level? I didn’t look to unseat the longtime mayor. Clinton Young is a guy I grew up with. I’ve seen the work he’s done as a legislator, and with the Boys and Girls Clubs, in helping us out. He asked for my help, and I said, “Hey, this is a guy I believe in.” It had nothing to do with disliking the other man. But you know how it goes. Once you say that, then the spin starts. All the more reason for me to stay out of it. People are always asking me, “Well, who do you like?” I say, “I’m sitting back, watching, listening to what everybody says. And then I’ll make a decision.”

The Great Debaters is all about African Americans breaking the shackles of racism. Without putting you in the position of making an endorsement, how important is it that Senator Barack Obama has emerged

as a frontrunner in this presidential race? Senator Obama should be taken seriously in this race. He’s a serious candidate, very intelligent. It’s time. It’s past time. The fact that he’s gotten such strong support — see, now, this is going to sound like an endorsement — just by talking about him, that’s what happens. I don’t mind talking about him. He’s intelligent, bright and he has great ideas and brings a youth and energy that this country needs. It goes back to what we were saying about the bad guys in the movies. Maybe this is an odd connection. But young people want some fresh ideas. I don’t think they’re happy about the way things are going. It’s much like when Kennedy came along in the late ’50s. The country was ready for some fresh blood, for some optimism.

Ronald Reagan and now Fred Thompson have gone from acting to politicking. Do you ever see yourself running for political office? Heck, no.

Why? No. I’d never say never, but… I don’t know. Arnold has done a good job, people in California love him, but this was something he really wanted. You really have to love it. To take that beating, you’d better want it.

What do you want? Well, I’ve got what I want. [Long pause] More? This chapter in my life, the directing — I’m loving that. And I’m loving watching my kids grow up. We sat there today, on Oprah, and there’s one kid in this movie, Denzel Whitaker, and I can’t believe that’s his name. But he’s about sixteen, and they’d all written journals during the film, and in his, he wrote down everything I said to him: on movies, on auditioning and on life. One of the things he said stuck with him was, “Keep it simple.” I got that from my mother, who always said, “Keep it simple.” As you get older, it’s more about clearing away weeds than planting new plants. To be able to continue and direct films, to produce films, to go into business with my kids, that’s enough. I don’t need anything more.

Now that you’re in your fifties, has your approach to life, and acting in general, changed? Because the last five years of my life were dominated by directing two films, it has changed my approach to life. After directing my first film, it was tricky and hard on the directors I worked with. Suddenly, I got ideas. Why are they putting the camera over there? Suddenly, I had to get used to being just an actor, again. It’s more interesting to me, in that I’m always developing other projects between acting jobs — continuing to develop films to direct. I’ve found that I need to stay busy.

Matt Damon was recently named People magazine’s Sexiest Man Alive, a title you once held. Do you have any advice for him? Now somebody told me that was a goof, that George Clooney and those guys were behind that. I don’t know. I’ve got no advice. But what did happen to those other guys? Were we only sexy for 365 days?

When was your reign? I don’t even remember. It was around the time of Malcolm X. So that was a long time ago. I don’t have a copy of that magazine. People can send me a copy, because I don’t have one.

It doesn’t sound like you took advantage of the title. I guess I didn’t. I could have stood on the corner, next to the newsstand, reminding people, “Hey, that’s me, that’s me.” Actually, I don’t know what that means. There are so many people in the world, and I am Sexiest Man Alive?

Didn’t it buy you something with the wife? Oh, I don’t think so. She knows the truth. Out of that title, I’ll just take the “Alive” part. Just being alive is the important part. Maybe one day I’ll win the Barely Alive Man of the Year. But I feel alive now.