I exaggerate the dangers, and all the disasters that might occur. I look quite serene to my staff, but I am like a woman in labor. Once I have made up my mind, everything is forgotten, except that which leads to success.”These words — strictly speaking — originated with Napoleon Bonaparte, but they could as easily have been the credo of Stanley Kubrick, who distilled them from the more than 500 volumes of research he amassed before piping them into the heart of his 1969 screenplay, Napoleon. “The art of war is a simple art,” this aria continues — and again these words speak as much for this particular filmmaker of genius as for the conqueror of Europe. “Everything is in the execution. There is nothing vague in it. It is all common sense. Theory does not enter into it. The simplest moves are always the best.”

I exaggerate the dangers, and all the disasters that might occur. I look quite serene to my staff, but I am like a woman in labor. Once I have made up my mind, everything is forgotten, except that which leads to success.”These words — strictly speaking — originated with Napoleon Bonaparte, but they could as easily have been the credo of Stanley Kubrick, who distilled them from the more than 500 volumes of research he amassed before piping them into the heart of his 1969 screenplay, Napoleon. “The art of war is a simple art,” this aria continues — and again these words speak as much for this particular filmmaker of genius as for the conqueror of Europe. “Everything is in the execution. There is nothing vague in it. It is all common sense. Theory does not enter into it. The simplest moves are always the best.”

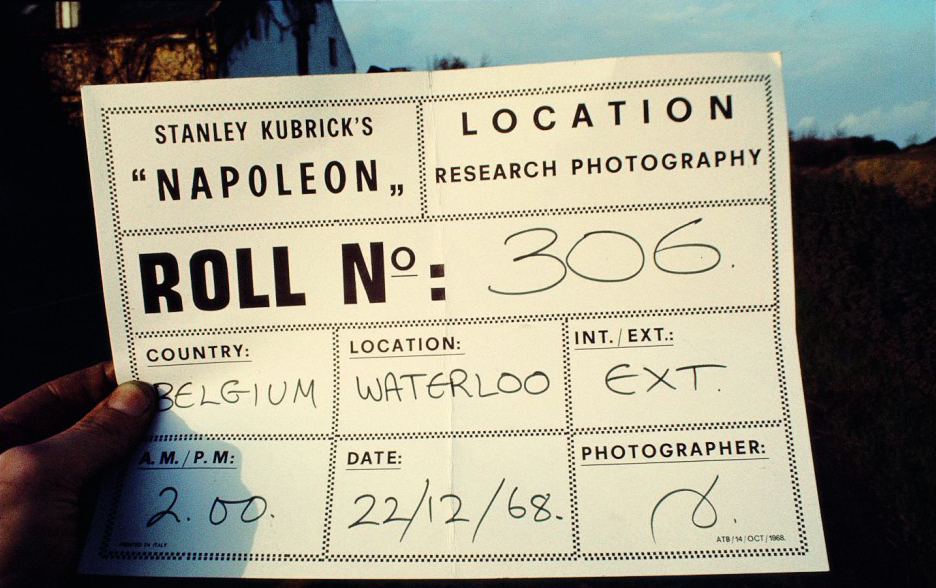

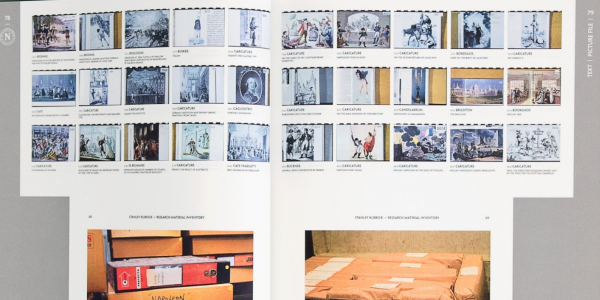

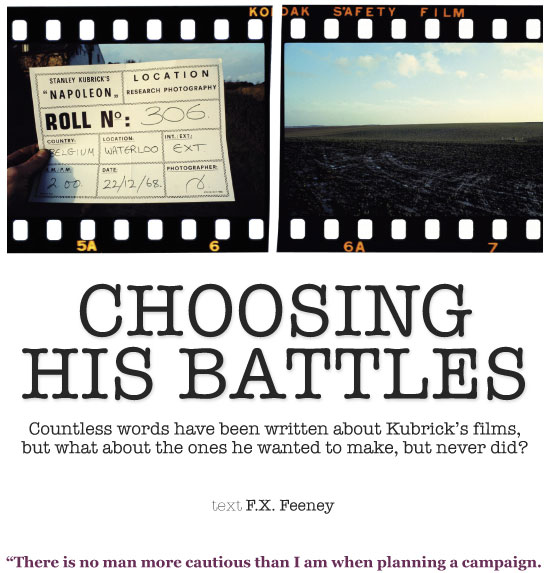

Napoleon was supposed to be Kubrick’s next film after 2001: A Space Odyssey. The final 148-page screenplay was completed September 29, 1969. The Romanian cavalry was engaged — between 15,000 and 50,000 strong, as needed for the bigger battle scenes, all for a projected $2 dollars each per day. Special costumes were commissioned from a New York firm, to be mass-printed on a “fireproof, drip-dry paper fabric which has a tear-strength of 300 pounds even when wet, for $1 to $4 depending on the detailing,” according to Kubrick’s post-script memorandum to the studio. “We have done tests on the $4 uniform and, from a distance of 30 yards or further away, it looks marvelous.” There was even a shooting schedule — ideally, July to September; “150 days, allowing 10 days lost to travel” — and a penciled-in cast that included Jack Nicholson as Napoleon and Audrey Hepburn as Josephine.

“The reason it was abandoned is simple,” explains producer Jan Harlan: “Dino DeLaurentiis was bringing out a big film with Rod Steiger called Waterloo, and the studio got cold feet. Stanley understood — that’s the business — but his would have been such an interesting film.”

We can only imagine.

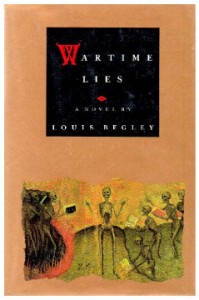

Indeed, in a string-theory universe parallel to the dozen masterworks Kubrick did complete, there are at least three unmade films that we can now conjure in considerable detail, and quite a few others from much earlier in his career whose skeletons illuminate a vivid prehistory of the wonders we do have. In addition to the Napoleon script and other production materials published by Taschen in 2009, we have Wartime Lies — also known as Aryan Papers — nearly filmed in 1993. Artifacts from both fill a set of rooms in the splendid Exhibition: Stanley Kubrick, presently anchored at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art until June 2013. We also have A.I. — Artificial Intelligence, which is not part of the museum show, conceived and developed by Kubrick from a story by Brian Aldiss but completed by Steven Spielberg — fittingly, in the year 2001.

“Stanley was keen to do A.I.,” says Harlan, who started as his researcher in the early 1960s, not long after his sister Christiane married Kubrick, and — with A Clockwork Orange — became his producer. “He loved the story of A.I. He began it because he loved Spielberg’s E.T. — he and Steven formed a mutual-admiration society. In the end, he offered it to Spielberg. Ironic, isn’t it?”

Leon Vitali, who costarred in Barry Lyndon and then stayed on to work closely with Harlan as co-producer on every Kubrick film that followed, recalls that the biggest obstacle to his moving forward with A.I. in the 1990s was technical, and conceptual — Kubrick was reluctant to cast a human actor as the robot boy. “At the rate I work, he would grow up too fast,” he joked to a number of people.

He reviewed a number of options in depth. Spielberg’s E.T. had been created with a marvelous puppet. Might an artificial boy be conjured the same way? “He had somebody working on robotics to create a lifelike boy,” says Vitali, “but the technology was not there yet, particularly in terms of facial expression. Stanley explored ways of augmenting this with CGI, but the morph line was difficult to determine, and at that stage, none of the special effects were matching up. He decided to put it on hold.” again, and he did it “as a monument to Stanley.” It is that, and more — a rare, fraternal instance of a film that fully belongs to two directors.

A deeper obstacle was one Kubrick acknowledged within himself. “The right guy for this might actually be Spielberg,” he told Jan Harlan at several points. “If I do it, it will be too bleak, too philosophical.” After setting it aside for Eyes Wide Shut, he offered the project to Spielberg, who turned it down. Later, after Kubrick’s death, Spielberg said Harlan approached him

“There is no deliberate pattern to the stories that I have chosen to make into films,” Kubrick told French film critic Michel Ciment in 1971. “About the only factor at work each time is that I try not to repeat myself.”

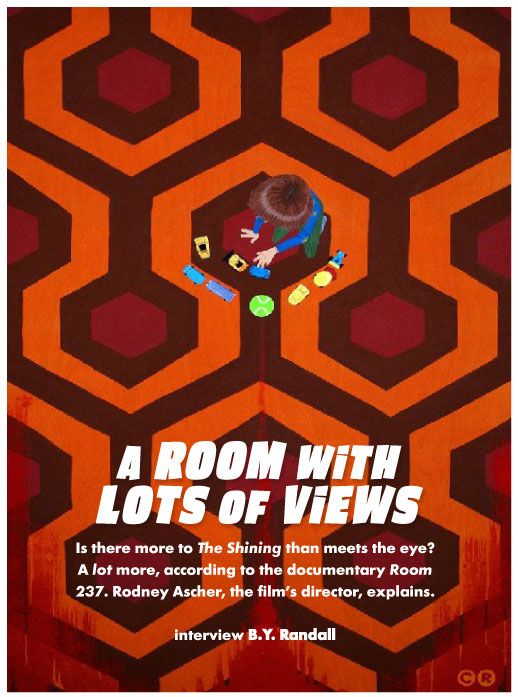

That quest is what makes his roads-not-taken so profoundly fascinating. Napoleon, Wartime Lies and A.I. are each as different from one another in basic premise as they are from anything else he directed — yet one is quickly struck by subtle continuities. Because we have Barry Lyndon, we can imagine Napoleon with some richness when we read the screenplay. Because of the protective mother-and-son alliance that so indelibly defines the outcome of The Shining, the young heroine protecting her nephew from the Nazis in Wartime Lies and the bereft mother bonding with a robot in A.I. tread upon a familiar terra firma in the Kubrick dream-world, however diverse their adventures.

From an early age, he took a long view. Passionate as he was about photography from the moment his father gave him the family Graflex, young Kubrick was also pragmatic to his marrow. When he was sixteen, the sight of a news vendor looking singularly dejected under the row of headlines reading “FDR DEAD” prompted him to snap a photo and approach Look magazine — which bought it on the spot, and soon hired him. “Recording spontaneous action, rather than carefully posing a picture, is the most valid and expressive use of photography,” he told his first interviewer, three year later — speaking now as a veteran journalist of 19. He let it be known he was becoming a moviemaker. By 22, having made two documentary shorts in wide distribution, no lesser paper than The New York Times reported he was headed to California to make his first feature — what would become Fear and Desire (1953) — about four soldiers trapped behind enemy lines and, as Kubrick told the Times, “their search for the meaning of life and the individual’s responsibility to the group.” What most impressed the reporter — but would surprise nobody now — was that, even as union regulations required young Kubrick to hire a professional cinematographer, “the one requirement is that the cameraman must agree in advance to follow the blueprint laid out by Stanley, who will direct and produce the film.”We tend in retrospect to think of Kubrick learning his craft in obscurity. On the contrary, that he was not only performing at a high level, but getting himself written about so prominently in the act, shows not just artistic prodigy, but a strategic sense uncanny in one so young, especially in the early 1950s.Small wonder he came to feel such kinship with Napoleon Bonaparte. After all, the budding conqueror became a sub-lieutenant when he, too, was only 16, after graduating from the Royal Military School in Paris; devoted several years in the ranks to the ardent study of arms and forward-thinking field tactics; then, at 23, launched himself to fame with a bold victory in the siege of Toulon. Kubrick later pointedly emphasized these facts on paper. In a screenplay constructed of otherwise purely filmable action, admirably devoid of purple “interior” writing, he permits himself a tiny indulgence when Napoleon clears his throat at Toulon to make the suggestion that will ignite his career before a roomful of staring officers: “Napoleon speaks with the uncomfortable yet determined manner that shy but extremely willful people often exhibit.” All historically accurate, of course, yet — takes one to know one — who but Kubrick could have taken us inside this particular leader with such light-sharp scrutiny?

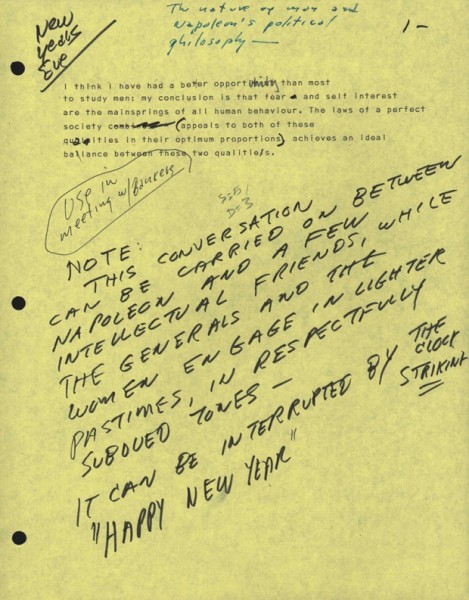

“The sheer drama and force of Napoleon’s life is a fantastic subject for a movie biography,” he told Joseph Gelmis in 1969. “He was one of those rare men who move history and mold the destiny of their own times and of generations to come — in a very concrete sense, our own world is the result of Napoleon, the way the political and geographic map of Europe is the result of World War II. …All of the issues with which [his story] concerns itself are oddly contemporary — the responsibilities and abuses of power, the dynamics of social revolution, the relationship of the individual to the state… This will be a film about the basic questions of our own times.”

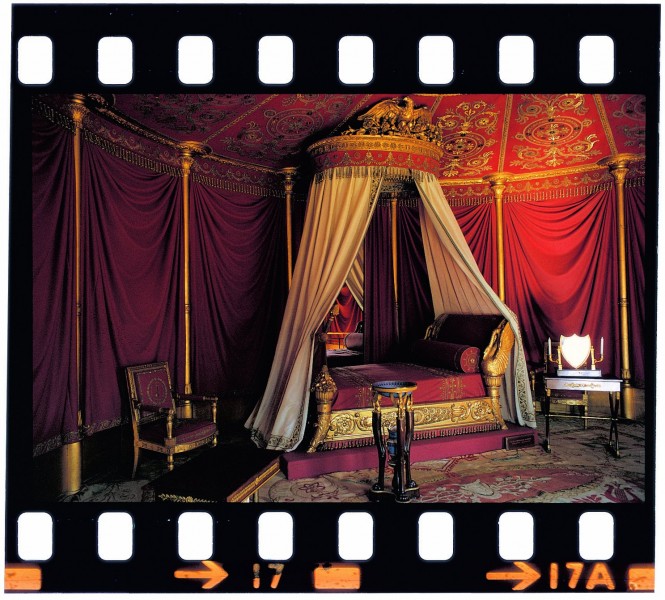

And yet — as if determined not to repeat the grand. galactic view of 2001, Kubrick took care to emphasize, invoking the Austrian novelist whose work would later inspire Eyes Wide Shut: “His sex life was worthy of Arthur Schnitzler… Forgetting everything else, and just taking Napoleon’s romantic involvement with Josephine, you have one of the great obsessional passions of all time.”

These passages, narrated in contrasting voiceovers lifted from the couple’s actual love letters (both were superb self-dramatizers) form a highly effective erotic counterpoint to the marches of revolution and history, and establish a level of psychological intimacy that Kubrick would not fully realize until Barry Lyndon or Eyes Wide Shut.

Was he conscious of this connection between what was unfulfilled in Napoleon and what he brought off later?

Not long after Lolita wrapped production, Kubrick and Harris pursued The Passion Flower Hotel, Rosalind Erskine’s comic novel about a brothel in an all-girls’ boarding school that later became a film starring Nastassja Kinski.

“That ‘connection’ you describe is a journalistic invention,” scoffs Harlan, “highly irrelevant to Stanley’s way of working. You connect Barry Lyndon because of the period, but what interested Stanley in Napoleon was the connection to our world now; that we are making the same mistakes today. We are engaging in stupid wars and destroying ourselves.”

Vitali likewise cautions against “facile” conclusions but allows for deep and unmistakable continuities: “I call it Stanley’s ‘core’ filmmaking,” he says. “I defy you to find a Kubrick film that repeats any other Kubrick film, and yet — in every context, whatever he is pursuing — there is a tangible quality you can’t quite put your finger on, something that tells you: ‘Yes. This is by Kubrick.’”

The unrealized projects of his early Hollywood period follow the Bonaparte playbook in terms of energy and daring. Young Kubrick had made two colossal but instructive blunders on Fear and Desire — one being costly but simply technical. He shot the picture without sync-sound in the mistaken belief that adding dialogue and effects after the fact would be a money-saver — only to end up tripling his budget. The other was not mapping out a strong enough narrative. He completed and released the picture despite that first obstacle, which is a tribute to his all-conquering determination — and a lesson learned. For the rest of his life he would always think through the challenges and costs of any idea with a precision that endeared him to studio bosses. The lack of a thoroughly worked-out story was, on the other hand, a private Waterloo he suffered more painfully. He suppressed Fear and Desire once he had the means to buy back all but one of the prints, and never again left himself open to such a derailment. Thereafter, he would work himself, his writers and his research teams ultra-hard so as to go into battle with the strongest possible story.

He and Howard O. Sackler — who co-wrote Fear and Desire — rebounded with a screenplay they called Along Came a Spider. The title intentionally suggests a fairy tale, and by diametric contrast to their war fable, they constructed exactly that — an action-driven yarn about a princess (make that a dance-hall girl) in the clutches of an ogre (make that a gambling promoter and crime boss) and the young knight (make that a boxer) who slays the monster and rescues the maiden. As James Naremore recounts in his book On Kubrick, the young director submitted this script to Joseph Breen of the production code office, “who rejected the project on the grounds that it contained ‘scenes of nudity and suggested nudity, excessive brutality, attempted rape, illicit sex, treated with no voice of morality or compensating moral values.’” Breen sounds as if he’s prophesying A Clockwork Orange.

Kubrick scaled back the sex and violence, and the result was his second dramatic feature, Killer’s Kiss (1955). This was his more definitive launch as a director. He picked up a major distributor in United Artists, and attracted the partnership of a dynamic partner and creative ally in producer James B. Harris. Together the pair transformed Lionel White’s novel Clean Break into The Killing (1956). Harris had deep enough pockets to acquire the rights to books if need be. For the rest of his career, Kubrick’s films would either be based on existing novels, or — in the case of 2001 — would involve collaboration with a novelist, such as Arthur C. Clarke. Only Napoleon is an “original” screenplay, derived from oceanic research — yet even in this case, Kubrick settled on the work of a single historian, Felix Markham, with whom he made a legal arrangement.As they were setting up The Killing, he and Harris pitched another Lionel White novel, The Snatchers — which detailed a kidnapping — and were turned down for the same reasons Breen rejected the first version of Killer’s Kiss, the more sordid but authentic aspects of the tale flew in the face of censorship. They next proposed So Help Me God, based on Felix Jackson’s muckraking novel about the Hollywood blacklist. This was completely unacceptable to the folks at the production code office. Naremore quotes a letter that all but squirms between tormented qualifiers in reply to Kubrick and Harris: “a picture which would seem to have as its aim the discrediting of the Un-American Activities Committee would appear to be of such a highly controversial nature that it might get into the area of questionable industry policy,” and so on. Next, they pursued Calder Willingham’s novel Natural Child, which was again bounced back as “basically unacceptable,” as it dealt frankly with abortion and sexually liberated characters living in Greenwich Village.

At one point, they worked up an idea for a TV series set in a military academy with comedian Ernie Kovacs — an ingenious surrealist who died far too soon, in 1962. Kovacs worked up a treatment, loosely based on a pompous army captain he’d played in Operation Mad Ball (1957), then he, Kubrick and Harris went to meet with the head of a Los Angeles military school, by way of research. “We didn’t tell the guy that we were out to do a satire. Ernie walked in flattering the guy, and laid it on so thick that Stanley and I got the giggles. We almost gave the game away.”

Other possible projects, such as developing a western with Marlon Brando, eclipsed this idea. Kubrick suggested calling it “One-Eyed Jacks,” an intriguing three-word combination of the type he liked to employ in a title – Full Metal Jacket and Eyes Wide Shut being later inventions. Brando had wanted to call the picture “A Burst of Vermillion.” Not long after Lolita wrapped production, he and Harris pursued The Passion Flower Hotel, Rosalind Erskine’s comic novel about a brothel in an all-girls’ boarding school that later became a stage musical scored by John Barry, and still later a film starring Nastassja Kinski.

“We felt so hogtied by the production code seal that you needed in those days to release a picture that we talked seriously about doing a sexually explicit film,” Harris recalls. “Mind you, all this was very speculative. Stanley’s idea was that you could film something honest and uninhibited with talented actors — that it could be beautiful, and truthful, and even tell a story.” Kubrick later discussed the same thing in more detail with writer Terry Southern, who made that conversation the basis for his novel Blue Movie. “But,” says Harris, “I wasn’t part of that conversation. And I want to emphasize that Stanley wasn’t thinking of porno — just something beyond the code seal. The problem in the mid-1950s was: Where do you show such a picture? Without the seal, you couldn’t advertise in newspapers, you couldn’t legally show it in theaters. Stanley even researched islands that were close to the coast of the United States but outside the three-mile limit.”What we can discern from these efforts is twofold. On the one hand, there is simple evidence of the courageous taste that would over time lead Kubrick and Harris to their greatest commercial success, Lolita, in 1962. On the other, we can witness an astute, downright systematic campaign of testing, provoking and evaluating.

“What would you say is the single most difficult tactical skill to master,” Czar Alexander asks Napoleon, during a brief moment when they are on friendly and even intimate terms. “Without a doubt, to estimate the enemy’s strength on the battlefield,” the Emperor replies. “This is something that is only acquired by experience and instinct.” Kubrick was actively honing both, despite that his earliest unrealized projects tended to stall at the proposal stage.Once The Killing established the pair as talents to watch, he and Harris briefly found a champion in Dore Schary, then studio chief at MGM. He wasn’t interested in Paths of Glory, a Humphrey Cobb novel the pair had optioned and hoped to develop — it was too close in theme and setting to Schary’s most famous flop, The Red Badge of Courage — but instead he invited the pair to dig through the vault for an MGM property that might appeal to him.

“We signed a contract with MGM,” recalls Harris: “Forty weeks for $75,000, for the two of us. We dug through the projects in the MGM archive as Dore suggested and chose to develop a Stefan Zweig story, The Burning Secret. Stanley had two favorite writers — Zweig, and Arthur Schnitzler. He always wanted to do things they had written — Eyes Wide Shut was based on a novel of Schitzler’s — but once he settled on Zweig, Stanley told Dore: ‘We’ll need a writer.’ Dore said: ‘That wasn’t our deal!’ Stanley said, ‘You have a writer under contract — Calder Willingham — though you’ve got him in Ceylon right now.’ Calder’s novel End As a Man was being filmed by MGM in Florida, and I guess he was in everybody’s hair, so the studio sent him halfway around the world to do rewrites on Bridge on the River Kwai. Dore said, ‘For Chrissakes, these forty weeks of yours are going by!’ But six weeks later, Calder came back.”

Here again, healthy battlefield logic — Kubrick went in prepared for Schary to squawk about “our deal,” already armed with an MGM writer to propose in reply — not to mention a creative Long View. His interest in Schnitzler’s work would ripen across the next forty years until Eyes Wide Shut closed his life on a symphonic note. In the short term, such diligence brought Harris and Kubrick a valuable creative partner in Willingham, who would work on both Paths of Glory and Lolita, prior to their hiring the latter’s author, Vladimir Nabokov, to write the screenplay.

At one point, they worked up an idea for a TV series set in a military academy with comedian Ernie Kovacs – an ingenious surrealist. Kovacs worked up a treatment, loosely based on a pompous army captain he’d played in Operation Mad Ball.

Jim Thompson was another writer Kubrick championed. He particularly admired his novel The Killer Inside Me, but the rights had been snapped up. Instead he brought Thompson aboard to write dialogue for The Killing and Paths of Glory, and in the late 1950s, with Harris, commissioned him to write an original new novel, Lunatic at Large. “Stanley had a great practical sense of what people’s strengths are,” says Harris. “‘Thompson writes great dialogue,’ and it was absolutely true — that was the aspect of his writing that stood out, and which we could use. I have to admit we were underwhelmed when Thompson first turned in Lunatic at Large — it wasn’t up to his best — but he did a solid job for what we paid him. Unfortunately, this was a few years before there were Xerox machines, and Jim didn’t keep carbon copies. Shortly after he handed it over, we lost that one copy. The manuscript disappeared for decades. After Stanley’s death his family found it at the bottom of a storage container. Stanley’s son-in law, Phillip Hobbs, has been trying to set it up in recent years.”

Continuities abound between Kubrick’s past and future work and the variety of projects he and Harris were considering. In addition to the Zweig story there was I Stole 16 Million Dollars, later retitled God Fearing Man, based on the memoirs of a former priest turned legendary safecracker named Herbert E. Wilson. “The guy was living in Canada,” recalls Harris, “because he would have been arrested if he ever crossed back into the United States. We got MGM to spring for a plane ticket so he could fly down to Tijuana — and that’s where we went to meet with him, and flesh out the script.” After The Killing, any story combining crime, precision and chance capture would have been perceived by financiers as a project safely within the Kubrick wheelhouse — but, as he later told Michel Ciment, “Kirk Douglas didn’t like it, and that was that.”

The German Lieutenant, which Kubrick co-wrote with Richard Adams (no relation to the author of Watership Down), reads in outline like a mature expansion of Fear and Desire. Two German officers circa 1945, patriotic but not Nazis, conclude early that their side is losing the war. After a bleak journey through their crumbling homeland, they are further disillusioned to find that the wife of a dead buddy they’ve risked their lives to find is indifferent to her husband’s death. What’s more, they are ordered to parachute behind American lines and destroy a bridge, which both regard as a hopeless and even ridiculous errand, given that the allies are so plainly winning. Yet what can they do? They must comply, or seem to, or be handed to the Gestapo. Harris and he later sold the script to actor Jack Palance.Downslope, based on the Civil War story Downhill Slope by Shelby Foote about Mosby’s Raiders, was a never-completed screenplay that must have appealed to Kubrick because John S. Mosby, a law student turned guerilla leader, was — like himself, and like Bonaparte — a bookish man with an adaptable intellect and a ruthless clarity about his own limits and shortcomings. “I never won any fight with a bully as a boy,” Mosby once told the editor of his memoirs, “and the only ones I didn’t lose were because some grownup broke it up.” The duality between that picked-on boy and the legendary “Grey Ghost” he became in later battle would certainly have appealed to the guy who later brought Gustav Hasford’s “Private Joker” to life onscreen.After helping turn Hasford’s The Short Timers into Full Metal Jacket, Michael Herr wrote that crime and war appealed to Kubrick because of “the old and always serious problem of how you put into a film or a book the living, behaving presence of what Jung called the Shadow, ‘the most accessible of archetypes, and the easiest to experience.’ …War is the ultimate field of Shadow-activity, where all of its other activities lead you.” Or, as Flannery O’Connor put it: “the man in the violent situation reveals those qualities least dispensable in his personality, those qualities which are all he will have to take into eternity with him.”

Because he himself had been a child when Hitler came to power, and literally came of age – snapping that FDR DEAD photo – at the moment the war to crush the Nazis had been won, it stands to reason that this particular period and its dramas held a powerful fascination for Kubrick. His wife Christiane and her brother Jan had grown up in Germany. Their parents were gentiles who loathed the Nazis; their uncle Veit Harlan was a filmmaker infamous for directing Jud Susse, the 1940 melodrama that was the definitive specimen of anti-Semitic propaganda. There is an unattributed rumor on the Internet that Kubrick once contemplated using Veit Harlan as a key figure in a drama centered on Joseph Goebbels and his propaganda machine. Certainly this angle would be easier to research than most. “There was what I would call a ‘notion’ in doing that,” says Vitali. “With Stanley, we could start all sorts of ideas and some would remain just that, a notion. It got no further than that, really. Others got much nearer the mark of production.” Kubrick’s sense of a single personality disrupting the history of a continent found a readier protagonist in Napoleon Bonaparte – and when he thought of World War II, it was in more intimate terms, using characters who were not committed to any side but were – like his future wife and producer – born into it, or if grown up, surviving unpredictably.

“One project Stanley was nuts about for a time arose when we were in post-production for Full Metal Jacket,” recalls Vitali. “We developed some very rudimentary stuff on a French triple-agent named Henri Dericourt. He was working for the British while he was working for the Germans while he was working for the British.”

Indeed, after parachuting into his native France in 1943, Dericourt served energetically with the resistance but was arrested a year after the war ended and accused of treason. Several allied agents under his charge had been arrested and executed, and there was direct evidence from the German archives that Dericourt had betrayed them. He seemed destined for the hangman’s noose when British MI6 intervened at the trial and let it be known that they had ordered Dericourt to sacrifice those agents, the better to win the trust of the Nazis and throw them off the scent of the impending D-Day invasion.

“Stanley viewed it as a fantastic story,” recalls Vitali, “because how much does the government know, how much doesn’t it know? We made contact with people. We were doing basic developments, sketch outlines. One fact that caught Stanley’s eye and greatly interested him was that Dericourt had a code whose key apparently concealed somewhere within the edition of Aesop’s Fables that had been illustrated by Gustave Doré. Stanley stuck a copy in my hand, and said: ‘Find it.’ We stopped work on it not long after. Stanley never said why. Maybe the time wasn’t right. We were still heavily involved in finishing Full Metal Jacket.”

Another possibility that briefly caught Kubrick’s attention was the 1985 novel Perfume, by German writer Patrick Süskind. Set in the 1700s, it spins a romantic, violent tale akin to the Brothers Grimm, of a dreadfully rejected orphan who has a genius for distinguishing scents. He is able to detect and even steal the essential scent of an animal or person – if he kills them – and in his overwhelming rapture at the scent of virginal women at puberty he becomes a mass murderer, purely to retrieve those divine smells.“Stanley gave me a copy to read after he’d read it, and we talked about it. It was unique – what happens when a psychotic picks up on a kind of sign or signal that repeats itself in his psyche and will make him kill, and kill again. We both liked Werner Herzog’s The Enigma of Kaspar Hauser. The origins of Perfume were very much of that kind, a type of hero that we find in fairy tales – somebody that comes from nowhere; that nobody knows.”What stopped this project from happening?

“Stanley was fascinated,” says Vitali, “but in the end this book just wasn’t something he could throw himself into. As with anything he looked at, whether it is the Süskind book or the Dericourt material, the core of his decisions about whether to do something or not do it never reflected a negative opinion of the story – or the subject matter. His decisions were based on how attached he felt emotionally to any idea.”

Kubrick loved the premise – a trio of scholarly wits fabricate a mystical text as a spook on conspiracy theory, only to find themselves being stalked by secretive believers who take their joke seriously – but Eco wouldn’t part with it.

Other novels that interested him fell to wayside because they weren’t available, such as Umberto Eco’s 1988 Foucault’s Pendulum. Kubrick loved the premise – a trio of scholarly wits fabricate a mystical text as a spoof on conspiracy theory, only to find themselves being stalked by secretive believers who take their joke too seriously – but Eco wouldn’t part with it. He hated the movie that had been made of In the Name of the Rose. In the late 1960s The Beatles approached Kubrick with an offer to direct Lord of the Rings, to which they briefly owned the rights, but – having so recently struggled to create plausible ape-men in 2001 – Kubrick passed, being too keenly aware of the difficulties in those days of creating believable hobbits, elves and fairies.

“I must confess,” Kubrick once told Ciment, when asked about The German Lieutenant, I Stole 16 Million and the various other projects he’d contemplated in his early days, “I have never been subsequently interested in any of these screenplays.” This was likely because his later work so successfully consumes and surpasses whatever thematic interest those projects might have once held.

The one exception was The Burning Secret. “It’s a good story,” said Kubrick, “about a mother who goes away on vacation without her husband but accompanied by her young son. At the resort hotel where they are staying she is seduced by an attractive gentleman she meets there. Her son discovers this, but when mother and son return home, the boy lies at a crucial moment to prevent his father from discovering the truth.” Of all the various unproduced projects they developed, Harris recalls that this was the one that Kubrick seemed closest to. “I never quite understood Stanley’s fascination with that story, but for some reason it really hooked him.”The reasons are buried with Kubrick, if he ever knew them himself, but the fascination lives on in the form of the aborted project Wartime Lies, or Aryan Papers, to which a deeply tantalizing pair of rooms is dedicated in the LACMA exhibition.Louis Begley, who had turned novelist after a long career in the law, wrote Wartime Lies as fiction because “I didn’t think I could write a memoir, and I didn’t want to. I am not a historian… Invention was necessary to fill out the story.” As he explained to The Paris Review, the figure of Tania, the aunt who shields her nephew in Nazi-occupied Warsaw, is closely based on his mother. “And she has some traits that I wished my mother had had, but didn’t have. Perhaps no real woman could have had them.” Indeed, said Begley, the story is driven by a series of deceits, from its title on out: “The little boy Maciek, and his aunt and grandfather, survive by lying, by denying and falsifying their identity. Little by little, the quantity of lies grows; the authenticity and validity of practically everything becomes suspect. At least for Maciek… Living within an invented identity is not without consequences.”

Kubrick, responding to these layers, engaged in what his co-producer Leon Vitali called “a vigorous preproduction process. We devoted several months of focused time, location scouting in Czechoslovakia and Poland, all ready to set up an office in Holland.”

“This was in the early ’90s, after the Iron Curtain came down,” says Jan Harlan. A wealth of unspoiled locations had opened up in the former Eastern bloc. “I traveled through Czechoslovakia, Poland and Hungary, photographing everything relevant.”

The display cases in the exhibit are filled with spreads of Harlan’s finds — city streets and landscapes that are either unchanged since the early 1940s, or easily dressed. Kubrick also explored a series of interior spaces near London, at the former Ealing Studios — itself largely unchanged from that same period.

These appear as background in a series of screen tests Kubrick made with Dutch actress Johanna Ter Steege (The Vanishing; Immortal Beloved) before offering her the part of Tania. This is a particularly haunting artifact. A small room is devoted to it, with wall-sized images of Ter Steege modeling period clothes and responding to Kubrick’s unrecorded directions — all narrated in voiceover by the actress, who mixes her memories of this encounter with dialogue adapted from Begley’s novel. “I will go to the kitchen in a minute,” she tells the boy softly. “At the signal, say good night. Go into the bedroom, hide behind the door. Listen carefully. If I shriek? Take the cyanide.”

Ter Steege’s vulnerable luminosity, coupled with the quick cuts, costume changes, shadowy stairwells and wintry window casements, all steadily assessed by Kubrick’s camera gaze and cool Nordic lighting, tantalize our imaginations with a sense of what might have been. Among other unique aspects, it would have been the first of his films to have a female protagonist.Why didn’t he make it? “Very simple,” says Harlan. “Terry Semel, the CEO of Warner Bros., cautioned Stanley. ‘You realize,’ he said, ‘You’re coming in after Schindler’s List. You’ve been burned once by Platoon.’ Mind you, Stanley thought Platoon was a wonderful film — but — ”“But,” adds Vitali, when asked the same question: “Platoon went into production well after we’d begun shooting Full Metal Jacket. It had been shot, edited and brought out while we were still in the pipeline. Stanley understood that if he hadn’t taken the time he took to make his pictures, we would have been up there, out front. It was a pragmatic consideration. I was there in the room with Stanley as he called Los Angeles to get the figures on Schindler’s List, as it went into its first weekend of wide release — and these were very good, deservedly so. He had already said to me, ‘We may have to face the painful facts here.’ After he finished that conversation and put the phone down, he turned to me, picked up the synopsis we were using at the time — put it in the tray and said, ‘I guess that’s that.’”

A placard on the museum wall states that Kubrick scuttled Aryan Papers (“We always called it Wartime Lies,” says Vitali) because the subject of the Holocaust sent him into a depression. Ter Steege says so, too, in her narration of the screen-test footage. This was something she’d been told by Stanley’s widow, Christiane Kubrick, when they met years after the project’s collapse.

“Who wouldn’t be depressed?” says Harlan. “It is a depressing topic! He worked on it for a year!”

“Stanley was never depressed about anything,” counters James B. Harris. “In all the years I knew him, he could look straight at the darkest material and keep his sense of humor intact” — Dr. Strangelove, anyone? — “or at the very least he could look at it with morbid fascination.”

“Not depressed,” says Vitali, “but the research was draining. We’d seen so many documentaries, so much footage. There are so many still photos of the Holocaust.” Among the items on display are a row of books: Louis Begley’s novel, alongside a pair of thick histories: Soviet Partisans in World War II, by John Armstrong, and Raoul Hilberg’s The Destruction of the European Jews, open to a page detailing the actions of Jews who’d escaped the ghetto to fight Nazis in the forests outside Warsaw — probably the only “upbeat” touch in the book.

“Stanley,” protested Michael Herr, when Kubrick once made him a gift of the latter book, “right now I just don’t know if I want to read a book called The Destruction of the European Jews.”

“No, Michael,” Kubrick replied, “the book you don’t want to read right now is The Destruction of the European Jews — Part Two.”

How about postpartum depression? Ter Steege speaks of taking to her bed for two days when she received the blow that her chance to be directed by Kubrick had suddenly collapsed. How did Kubrick himself take the hit?

“Stanley wasn’t thinking of porno – just something beyond the code seal. The problem in the mid-1950s was: Where do you show such a picture? Without a seal, you couldn’t advertise in newspapers, you couldn’t legally show it in theaters.”

– James B. Harris

“Emotionally, relieved,” says Vitali. “Not in the sense of ‘Thank God,’ but just — a feeling of fresh air ,after all those miles of grueling footage. Bear in mind, he hadn’t given up on the project entirely. What he decided was simply that it was not for him. He was happy to look for a director who might be willing to take it on, with himself producing. So it didn’t completely die in that moment — but it departed from his mental cycle, and was gradually replaced with A.I., and because of the technical challenges that, too, was set aside for Eyes Wide Shut.”Had Kubrick lived — he would be eighty-four today — would he have returned to A.I., or Napoleon?“About Napoleon, I’m doubtful,” says Vitali, “Because that belonged to a very different ‘mental cycle,’ if you will. It didn’t happen at the moment in Stanley’s life when he was most prepared to make it, and I believe he moved on. On the other hand, he might well have returned to A.I., because the idea still excited him, and by 1999 the technology had caught up.

What would a Kubrick A.I. have been like? Here we enter the grounds of interesting controversy. Critics punished Spielberg’s A.I.: Artificial Intelligence when it premiered. Harlan and Vitali are both adamant that these attacks are unjust.

Speaking as one who named A.I. the best film of that year on my Top Ten list, and as one of the few film critics who has championed it in the years since, along with Jonathan Rosenbaum of The Chicago Reader and James Naremore in his book On Kubrick, I would like to offer a gentle but firm counter-argument to those skeptics who say: Stanley wouldn’t have done it that way, or, Too sentimental; too much like Pinocchio; that ending felt tacked on.

The film unfolds in four symphonic movements, as did 2001. There’s a Dawn of Man sequence — tracing the early home life of the mechanical boy, David (which was the name of the lead astronaut in 2001). There’s a trip to the moon — David’s flight through a fairy-tale wilderness, in which a large artificial moon figures. There’s a game of wits with a superior, possibly malign intelligence — “Rouge City” and its many denizens standing in for HAL. There is a trippy voyage through the gates of mortality — that haunting spectacle of New York, half-submerged in water. Moreover, each fresh stage in the hero’s evolution is prefigured by some violent act. Whereas Dave in 2001 murders HAL, David murders another robot boy, patterned after himself — and this act of primal rage provokes his next colossal step, an effort to take his own life that propels the boy through a cosmic gate (contemplating a carnival statue of the Blue Fairy for thousands of years on end) into an evolutionary leap in which he mysteriously succeeds at becoming “a real boy,” just as the astronaut in 2001 became superhuman.

“What Spielberg directed is very, very close to what Stanley wrote!” insists Harlan. “The Blue Fairy, the reunion with the mother, the whole Pinocchio idea — all of it was a very important part of Kubrick’s conception. It’s the driving element of the robot boy that he wants to become a real one. That’s the story — take it away, there’s no story!”

Would there have been a difference in tone? “Stanley would have used different music,” says Harlan. “He would have used the waltz from Richard Strauss’s Rosenkavalier. He would have included a scene in which the boy has a piano lesson — and the refrain would have become a theme. But that is a small difference, essentially — not at all substantial.”

Vitali agrees. “How anybody in the world could say, ‘Oh, it isn’t a Kubrick film because Kubrick wouldn’t have made it that way,’ is ridiculous. Nobody knows what he might have done. Even Stanley didn’t know. Name me one of his films which is the same as another of his films. When we shot a film with Stanley, it was evolving from day to day. He was bound to transform it. When you think of how long a shooting period was for him, just imagine how many pictures are rolling in his head. No, Spielberg did a terrific job — it was unfair, how harshly he was judged.”

One intriguing difference between Spielberg’s final film and the original Kubrick sorted out with Ian Wilson — paraphrased in the Taschen book The Kubrick Archive, for the treatment has never been published anywhere — is a speech given to Dr. Hobby (played by William Hurt in the film), in which he explains near the climax that David and others like him have been implanted with a “Blue Fairy” directive as a curious — and inadvertently cruel — experiment. We asked ourselves, what if we gave an Artificial Intelligence system a problem it could not solve? Would it develop a belief in God? Would it become neurotic or destructive? Would it undertake a quest?

This is in the deep end zone first navigated by HAL in 2001, whose nearly human mind becomes humanly murderous once it is programmed to lie. It’s too bad Spielberg shied away from this — but: Why complain? We have the film, and it is as primal and emotional as Kubrick hoped. And it benefits from Spielberg’s enormous warmth, for that conclusion set in the ice-world, post-humanity, is as bleak as they come.

“It’s such a black story,” says Harlan. “Humanity has disappeared! We’re not even told why. This was necessary. Stanley’s attitude was that, the way we behave, we have no chance of survival anyway. Whether it’s another 500 years or fifty: What’s the difference?”

What of posterity?

“Walter Salles pursued Wartime Lies for awhile,” says Harlan, “but it’s still out in the open. Warner Bros. owns it.”

As for Napoleon?

“I would certainly support it being made,” he says. “Of all the things in Stanley’s archive, that’s the fantastic one. What interested Stanley about Napoleon was not the period, but his influence on today. We’re making the same absolutely stupid mistakes, time and again. He went to war, and it killed him off. And he was such a brilliant man! It would need a big producer and a great director, but it could be done. You would have to do it with computer graphics because there are no longer any cavalries in the world.”

Kubrick was an artist of large preoccupations. Not just evolution and nuclear warfare — that’s the easy stuff. He was fascinated by the drama of child-rearing, whether at intimate range or across the ages, be it biological or symbolic; of how we teach others, and learn to teach ourselves. Tenderness and curiosity — even kindness — are not empty pastimes in the Kubrick universe; they are the fundamental tools of each child’s survival. Even his most hardboiled thieves and war-burnt soldiers are fundamentally children at heart. He is so straightforward and unromantic in his presentation of this — and the heart’s opposites: hostility, murderous will, warfare — that for a long time, many critics mistook him for cold. What was chilling was merely his perspective.

Napoleon opens on a teddy bear, cradled in the future Emperor’s arms, as he nestles in the arms of his devoted mother. It ends half a century later with Napoleon dead and buried on the remotest possible island, while his ancient mother, who has outlived him, rocks in a chair in Rome and stares silently at the same old teddy bear, which has survived the onetime boy as well. In context, this is a heartrending circle Kubrick describes — but need we grieve? That mother and that teddy bear were both reincarnated in A.I.

What’s more, the Napoleon script exists as a thing of beauty in itself — camera-ready, tight as a drum. For anyone who loves Kubrick, what he got on paper in the prime of his life — at that physical and mental apex he occupied in the wake of 2001 — is a grand movie in prose. We’re in the presence of an imagination so specific in its demands — on itself, on us; just as we are when watching his films — that even the things he left undone only bring us back all the more powerfully to the great things that he did do.