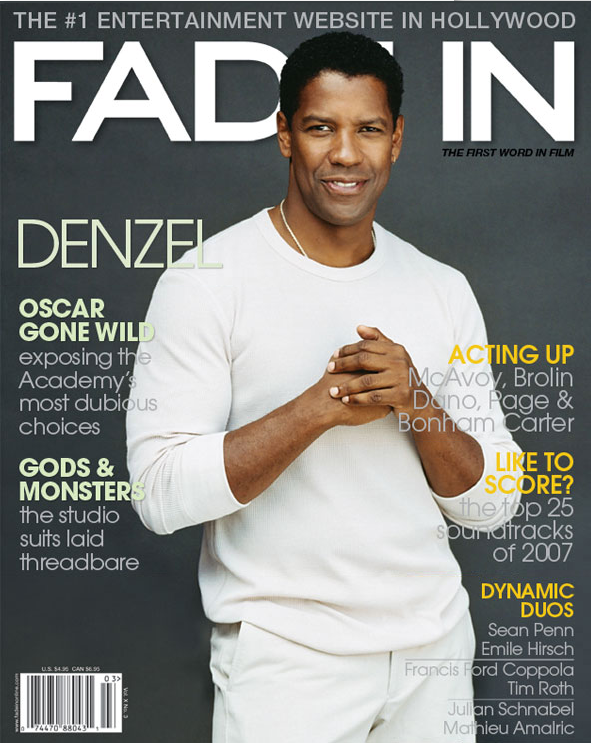

alk about stamina. Oscar turns eighty this year, yet he still remains Hollywood’s most lusted-after octogenarian. By the time you’ve reached your eighth decade, however, some self-reflection seems in order, and for both the past and present voting members of the academy, it’s a reckoning that could get ugly. At this age, competency hearings are not uncommon, and it’s with that understanding that Oscar is called into account.

alk about stamina. Oscar turns eighty this year, yet he still remains Hollywood’s most lusted-after octogenarian. By the time you’ve reached your eighth decade, however, some self-reflection seems in order, and for both the past and present voting members of the academy, it’s a reckoning that could get ugly. At this age, competency hearings are not uncommon, and it’s with that understanding that Oscar is called into account.

As the years have passed, time has not been kind to some of Oscar’s selections — OK, a lot of the selections. Space and sanity limit us to a dirty dozen of the most egregious, hair-pulling, groan-inducing, “Are you fucking kidding me?” decisions.

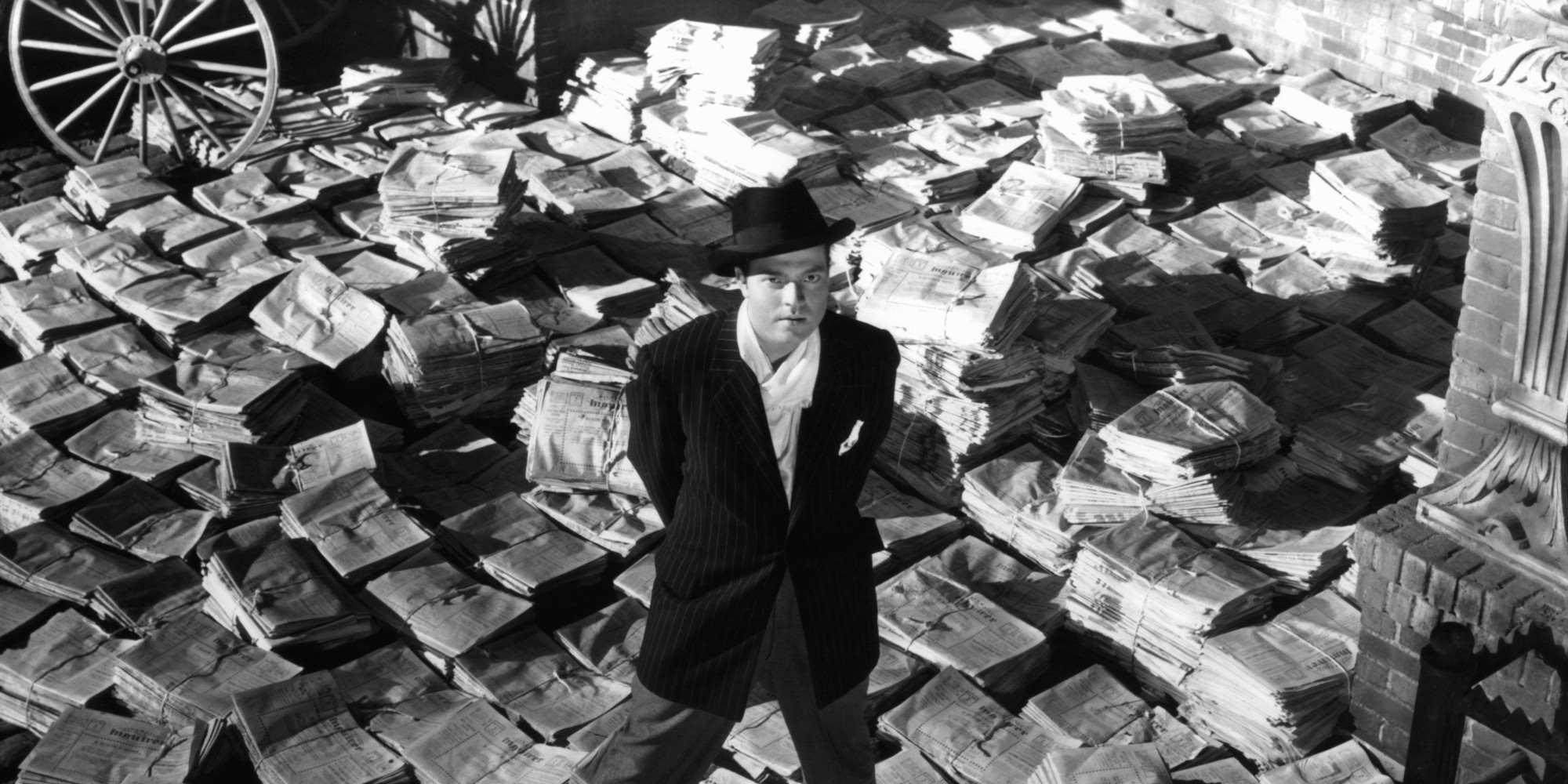

The Year: Best Picture 1941

The Verdict: How Green Was My Valley

The Appeal: Citizen Kane Valley, a genial tale of a Welsh mining family at the turn of the century, was a perfectly respectable choice. It certainly had a handsome pedigree. Adapted from a popular novel, produced by Darryl F. Zanuck, and directed by the legendary John Ford, it was classy with a capital “C.” (Never mind the fact that seemingly all the actors spoke with an Irish accent). The problem with the pick is that it bested what is routinely cited as the greatest film ever made. Over and over again. Decade after decade. The world had never seen a story told quite the way wunderkind Orson Welles did, and despite nine nominations, Citizen Kane went home with a meager screenplay award. Welles’ masterpiece was probably considered a little too revolutionary back then, and if there’s one thing Oscar tends to reward, it’s the comfort factor. No guts does not necessarily equal no glory as far as Oscar is concerned, a disturbing trend that continues to this day.

Valley, a genial tale of a Welsh mining family at the turn of the century, was a perfectly respectable choice. It certainly had a handsome pedigree. Adapted from a popular novel, produced by Darryl F. Zanuck, and directed by the legendary John Ford, it was classy with a capital “C.” (Never mind the fact that seemingly all the actors spoke with an Irish accent). The problem with the pick is that it bested what is routinely cited as the greatest film ever made. Over and over again. Decade after decade. The world had never seen a story told quite the way wunderkind Orson Welles did, and despite nine nominations, Citizen Kane went home with a meager screenplay award. Welles’ masterpiece was probably considered a little too revolutionary back then, and if there’s one thing Oscar tends to reward, it’s the comfort factor. No guts does not necessarily equal no glory as far as Oscar is concerned, a disturbing trend that continues to this day.

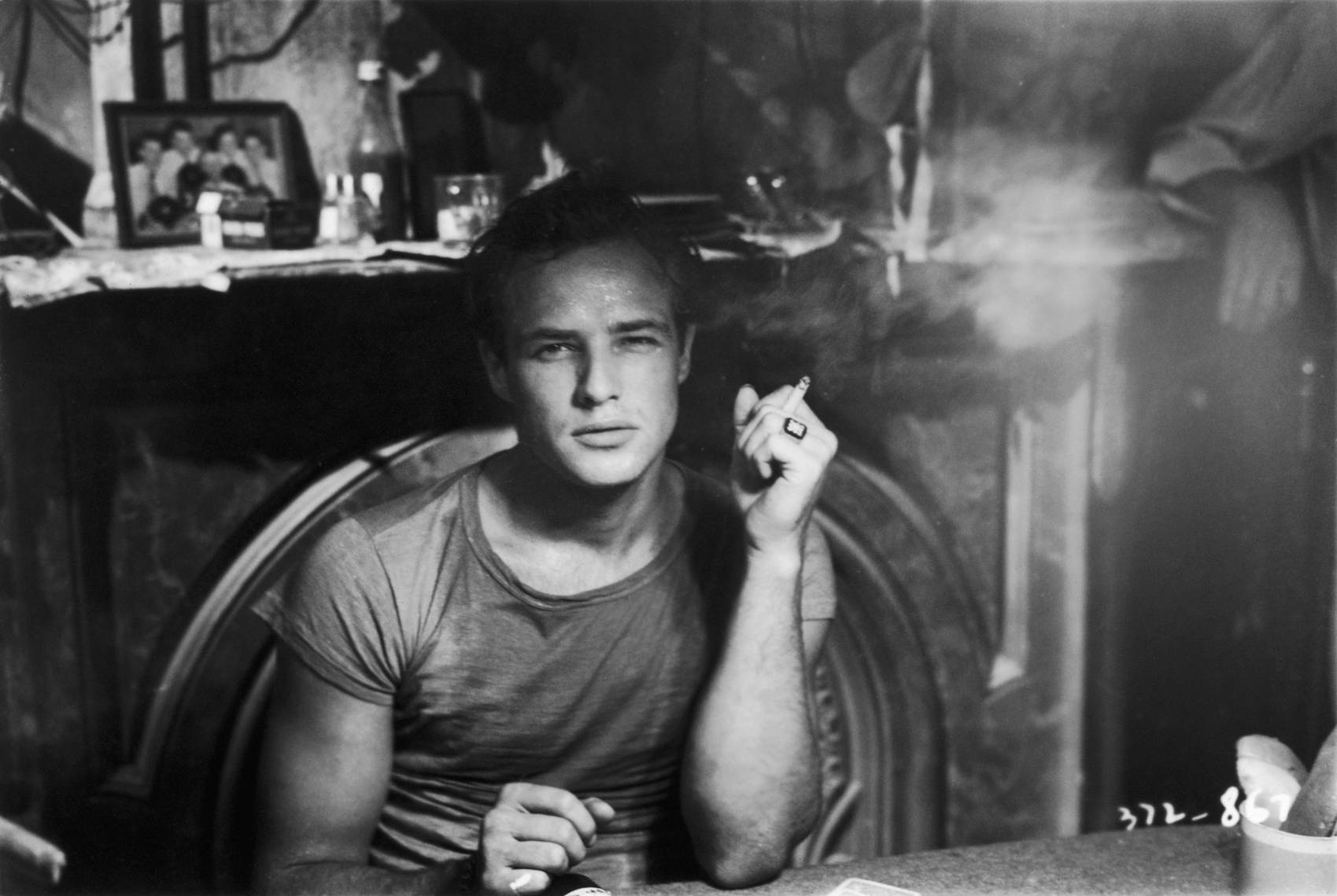

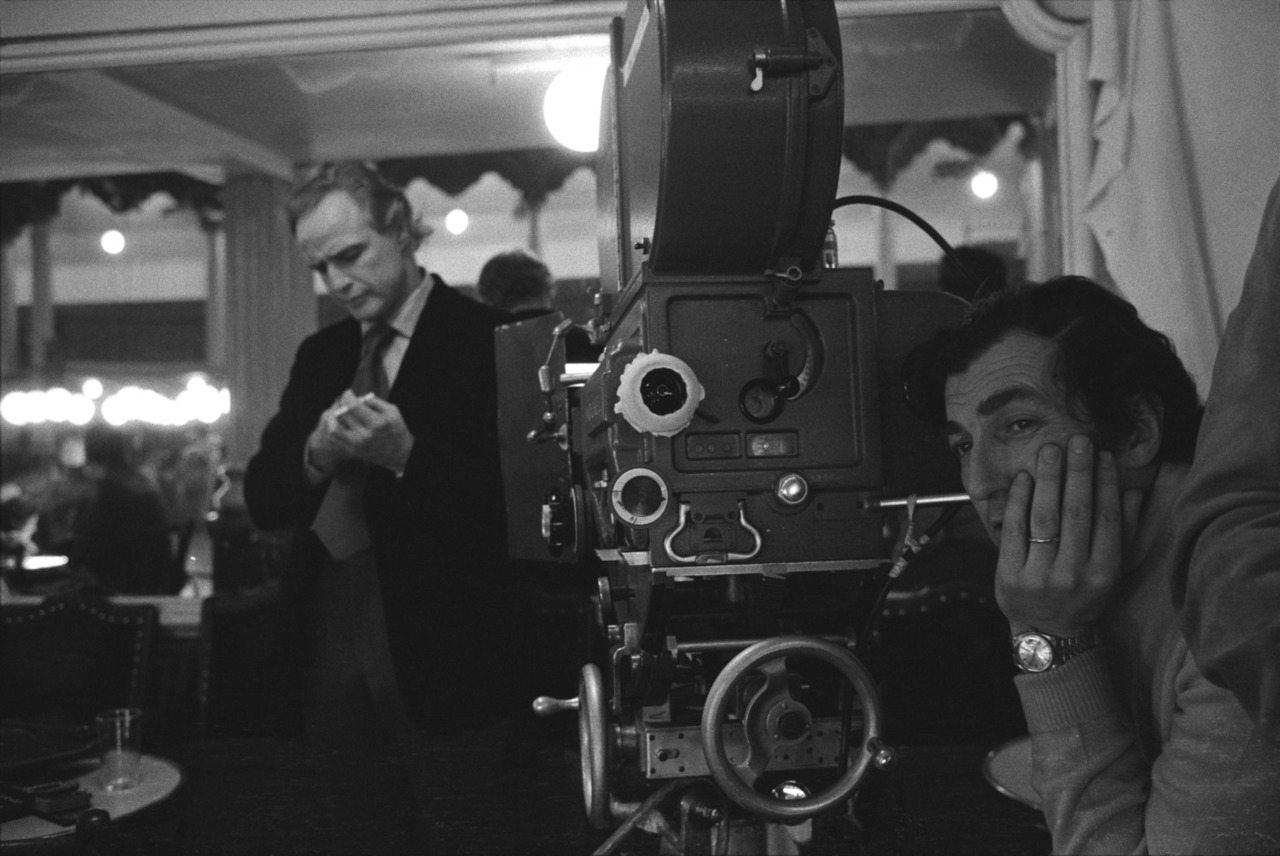

The Year: Best Actor 1951

The Verdict: Humphrey Bogart for The African Queen

The Appeal: Marlon Brando for A Streetcar Named Desire The revolution of contemporary film acting is generally regarded as the moment when Marlon Brando turned a T-shirt, an attitude and a mumble into iconic immortality as Stanley Kowalski in A Streetcar Named Desire. His performance transformed the entire profession and thrust it in a new direction, so it was natural that Hollywood would choose to embrace and reward such genius by handing him its highest honor, right? Are you joking? Oscar chose to go home that night with Humphrey Bogart, who crowned his career playing the besotted boat captain in The African Queen. Sentiment is a strong seducer, and the little golden guy fell for it hook, line and gin-soaked sinker. To be fair, Brando did win three years later for On The Waterfront, but one can’t help but wonder if his refusal of his second Oscar in 1972, for The Godfather, wasn’t tinged slightly with the memory of the night Bogie bested brilliance.

The revolution of contemporary film acting is generally regarded as the moment when Marlon Brando turned a T-shirt, an attitude and a mumble into iconic immortality as Stanley Kowalski in A Streetcar Named Desire. His performance transformed the entire profession and thrust it in a new direction, so it was natural that Hollywood would choose to embrace and reward such genius by handing him its highest honor, right? Are you joking? Oscar chose to go home that night with Humphrey Bogart, who crowned his career playing the besotted boat captain in The African Queen. Sentiment is a strong seducer, and the little golden guy fell for it hook, line and gin-soaked sinker. To be fair, Brando did win three years later for On The Waterfront, but one can’t help but wonder if his refusal of his second Oscar in 1972, for The Godfather, wasn’t tinged slightly with the memory of the night Bogie bested brilliance.

The Year: Best Actor 1964

The Verdict: Rex Harrison for My Fair Lady

The Appeal: Peter Sellers for Dr. Strangelove, Peter O’Toole and Richard Burton for Becket, Anthony Quinn for Zorba the Greek

Musicals have a tendency to be catnip for Oscar, and during the ’60s no fewer than four of them won Best Picture. One of the wispier choices was My Fair Lady, a lackluster pick that regretfully carried along Rex Harrison for re-creating his stage role as Professor Henry Higgins. This was sentimental slop of the worst kind, and one that willfully overlooked the rest of what was an amazing field of international actors. Peter O’Toole and Richard Burton in Becket were an Olympian pairing made in acting heaven with their roles as King Henry II and Thomas á Becket, respectively. They just had the bad luck to land in a year where the wrong Brit was recognized. Ditto for Peter Sellers, who was black-comic genius in Dr. Strangelove, playing three roles. His delivery of “Gentlemen, you can’t fight in here. This is the War Room!” remains the gold standard for hilarious absurdity. When a role becomes a lifelong association with an actor, it’s clear the performer has done something right, and that’s also the case with Anthony Quinn as Zorba the Greek. Thankfully, Quinn’s lusty, larger-than-life portrayal might’ve eluded Oscar’s embrace, but not the world’s.

Musicals have a tendency to be catnip for Oscar, and during the ’60s no fewer than four of them won Best Picture. One of the wispier choices was My Fair Lady, a lackluster pick that regretfully carried along Rex Harrison for re-creating his stage role as Professor Henry Higgins. This was sentimental slop of the worst kind, and one that willfully overlooked the rest of what was an amazing field of international actors. Peter O’Toole and Richard Burton in Becket were an Olympian pairing made in acting heaven with their roles as King Henry II and Thomas á Becket, respectively. They just had the bad luck to land in a year where the wrong Brit was recognized. Ditto for Peter Sellers, who was black-comic genius in Dr. Strangelove, playing three roles. His delivery of “Gentlemen, you can’t fight in here. This is the War Room!” remains the gold standard for hilarious absurdity. When a role becomes a lifelong association with an actor, it’s clear the performer has done something right, and that’s also the case with Anthony Quinn as Zorba the Greek. Thankfully, Quinn’s lusty, larger-than-life portrayal might’ve eluded Oscar’s embrace, but not the world’s.

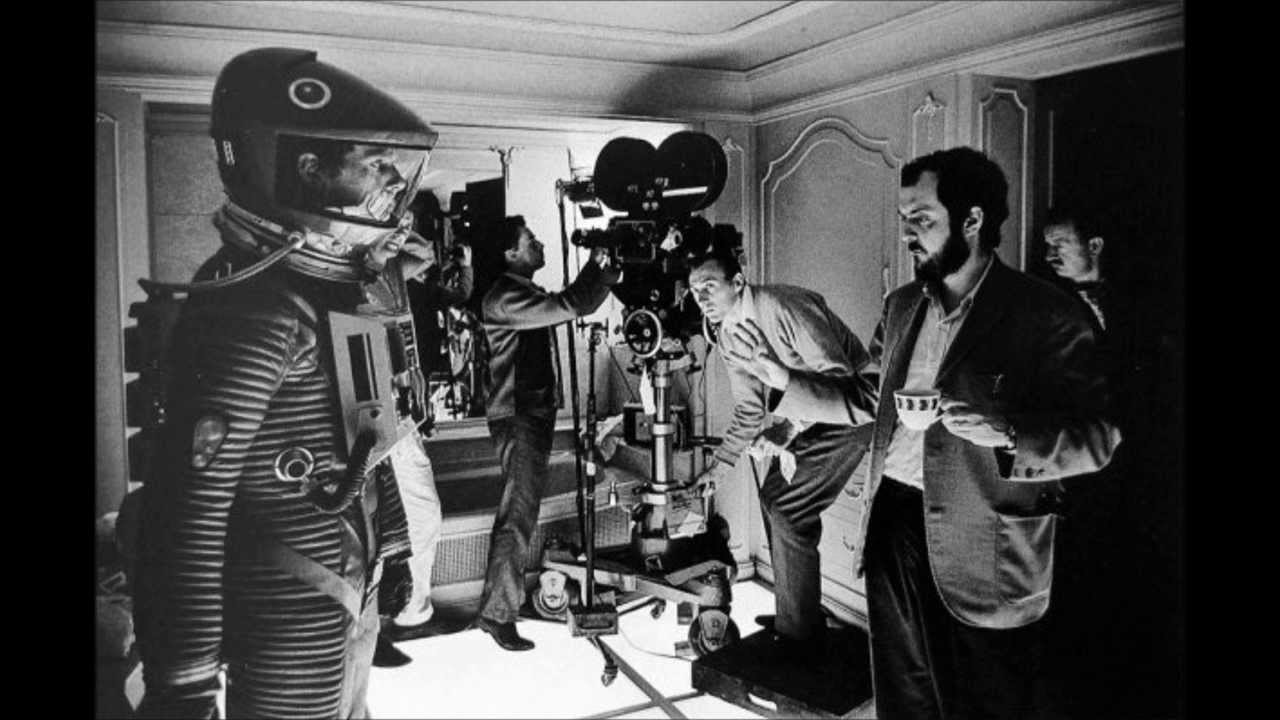

The Year: Best Director 1968

The Verdict: Sir Carol Reed for Oliver!

The Appeal: Stanley Kubrick for 2001: A Space Odyssey The choice of Oliver! for the Best Picture Oscar remains one of the darker stains on the academy’s ledger, and the long-overdue recognition of the film’s director, Sir Carol Reed, couldn’t have come at a more inopportune time. Thirty-plus years into a distinguished career that saw him create such masterpieces as The Third Man and Odd Man Out, Reed finally got his due from Hollywood. Alas, the honor came for this twaddle based on the stage musical of Charles Dickens’ Oliver Twist, about a bunch of pickpocketing orphans. It remains one of the worst redress awards when you consider Reed beat out Stanley Kubrick, whose landmark film 2001: A Space Odyssey was also inexplicably left out of the Best Picture category. Kubrick’s mind-bending, genre-defining magnum opus did earn Kubrick an Oscar for special effects, but his astounding vision of Arthur C. Clarke’s novel remains the granddaddy of all big-screen science fiction. Blissfully, it also depicted a future devoid of any scruffy, singing and dancing street urchins.

The choice of Oliver! for the Best Picture Oscar remains one of the darker stains on the academy’s ledger, and the long-overdue recognition of the film’s director, Sir Carol Reed, couldn’t have come at a more inopportune time. Thirty-plus years into a distinguished career that saw him create such masterpieces as The Third Man and Odd Man Out, Reed finally got his due from Hollywood. Alas, the honor came for this twaddle based on the stage musical of Charles Dickens’ Oliver Twist, about a bunch of pickpocketing orphans. It remains one of the worst redress awards when you consider Reed beat out Stanley Kubrick, whose landmark film 2001: A Space Odyssey was also inexplicably left out of the Best Picture category. Kubrick’s mind-bending, genre-defining magnum opus did earn Kubrick an Oscar for special effects, but his astounding vision of Arthur C. Clarke’s novel remains the granddaddy of all big-screen science fiction. Blissfully, it also depicted a future devoid of any scruffy, singing and dancing street urchins.

The Year: Best Director 1973

The Verdict: George Roy Hill for The Sting

The Appeal: Ingmar Bergman for Cries and Whispers and Bernardo Bertolucci for Last Tango in Paris Oscar is nothing if not a good host. He invites actors, writers and directors from all across the world to come partake of the festivities…and then usually sends them home empty-handed. Such was the case this year, when The Sting caught Oscar’s fancy and rode the con-man comedy to a seven-tiered Oscar sweep. Hill was an industry vet whose previous Paul Newman-Robert Redford teaming brought in buckets of cash with Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid, and then duplicated the success again with this affable effort, although most of the acclaim rightfully went to David S. Ward’s clever screenplay and Marvin Hamlisch’s jaunty Scott Joplin-driven score. Hill’s direction was efficient, but in light of the two European legends that competed against him, his effort was a profound piffle. Bergman had already directed a body of unrivaled cinematic classics, yet his work on Cries and Whispers, a family drama about three sisters, is arguably his finest hour. Bertolucci was just near the start of his storied career, and he blew the doors off stodgy cinema with his searing depiction of middle-aged malaise in Last Tango in Paris. Of course, any films that involve sodomy and genital mutilation aren’t going to curry too much favor with Oscar, as he is, for the most part, a fairly conservative type.

Oscar is nothing if not a good host. He invites actors, writers and directors from all across the world to come partake of the festivities…and then usually sends them home empty-handed. Such was the case this year, when The Sting caught Oscar’s fancy and rode the con-man comedy to a seven-tiered Oscar sweep. Hill was an industry vet whose previous Paul Newman-Robert Redford teaming brought in buckets of cash with Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid, and then duplicated the success again with this affable effort, although most of the acclaim rightfully went to David S. Ward’s clever screenplay and Marvin Hamlisch’s jaunty Scott Joplin-driven score. Hill’s direction was efficient, but in light of the two European legends that competed against him, his effort was a profound piffle. Bergman had already directed a body of unrivaled cinematic classics, yet his work on Cries and Whispers, a family drama about three sisters, is arguably his finest hour. Bertolucci was just near the start of his storied career, and he blew the doors off stodgy cinema with his searing depiction of middle-aged malaise in Last Tango in Paris. Of course, any films that involve sodomy and genital mutilation aren’t going to curry too much favor with Oscar, as he is, for the most part, a fairly conservative type.

The Year: Best Picture 1976

The Verdict: Rocky

The Appeal: All The President’s Men and Network Sure, everyone loves the story of the underdog. It gives you hope and, if even for a short while, validates the pursuit of a dream. Yes, Rocky is indeed a nice Cinderella story, but one that should’ve turned into a pumpkin well before its creator did. The fact that it won a scant three Oscars shows that even people who voted for it must’ve felt a bit silly, especially given the feel-good boxing saga’s competition. In one corner was the supposedly unfilmable adaptation of the bestseller All the President’s Men, which recounted the Watergate affair in gripping, superb storytelling style under the direction of Alan J. Pakula. In the other corner was the profane and prophetic Network, which produced three acting Oscars, as well as one for screenwriting legend Paddy Chayefsky. Combined, these two films cleaned up with eight awards, but were most likely cheated for the Big One because they were unable to seduce Oscar with lexicons that might have proved a bit too complex. After all, it’s harder to sell “rat-fucking” or “pseudo-insurrectionary sectarian” to voters when “Yo!” is so much easier to digest.

Sure, everyone loves the story of the underdog. It gives you hope and, if even for a short while, validates the pursuit of a dream. Yes, Rocky is indeed a nice Cinderella story, but one that should’ve turned into a pumpkin well before its creator did. The fact that it won a scant three Oscars shows that even people who voted for it must’ve felt a bit silly, especially given the feel-good boxing saga’s competition. In one corner was the supposedly unfilmable adaptation of the bestseller All the President’s Men, which recounted the Watergate affair in gripping, superb storytelling style under the direction of Alan J. Pakula. In the other corner was the profane and prophetic Network, which produced three acting Oscars, as well as one for screenwriting legend Paddy Chayefsky. Combined, these two films cleaned up with eight awards, but were most likely cheated for the Big One because they were unable to seduce Oscar with lexicons that might have proved a bit too complex. After all, it’s harder to sell “rat-fucking” or “pseudo-insurrectionary sectarian” to voters when “Yo!” is so much easier to digest.

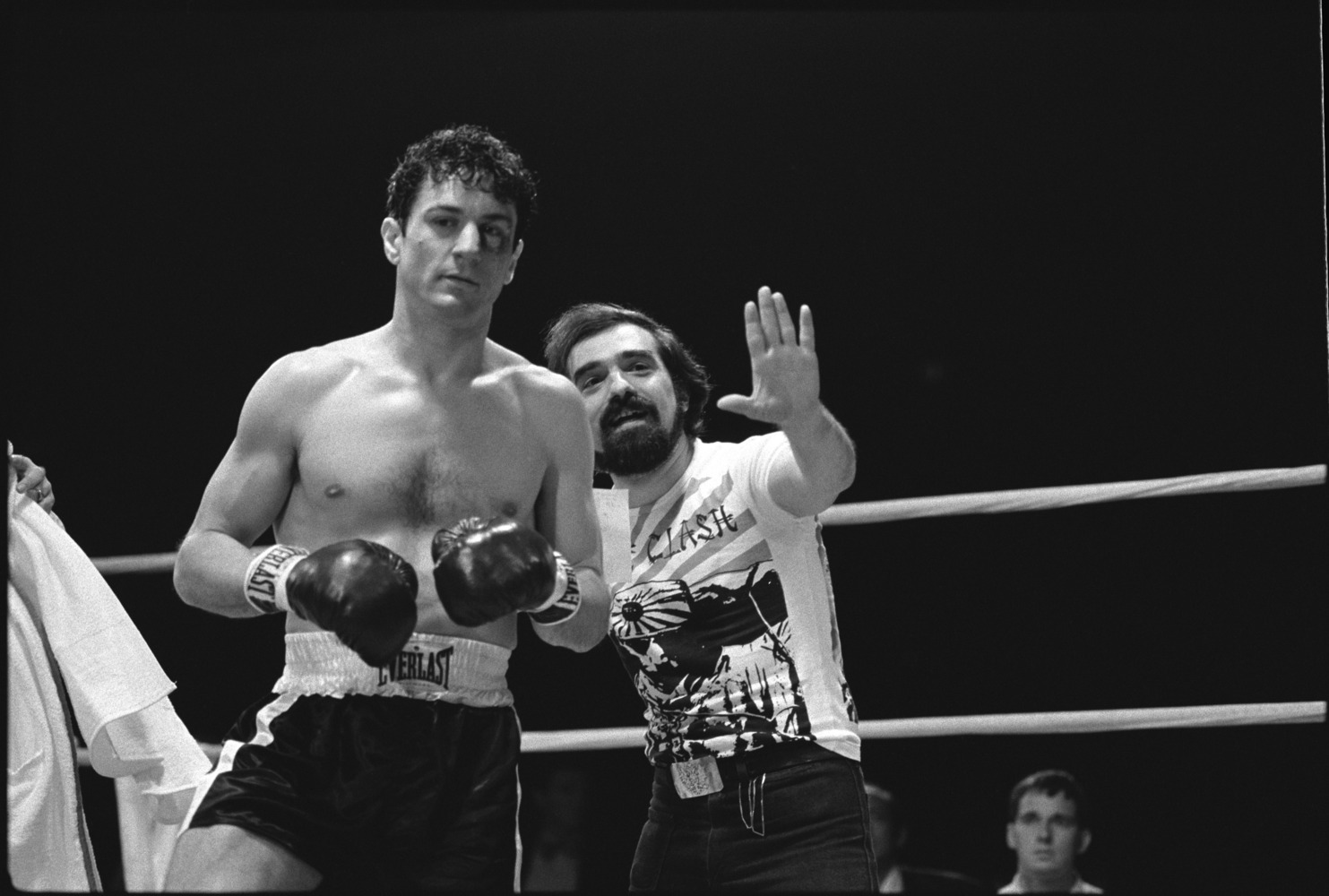

The Year: Best Picture 1980

The Verdict: Ordinary People

The Appeal: Raging Bull After the 1979 victory by Kramer vs. Kramer, this marked back-to-back years that family dramas made off with Oscar. Ordinary People was a quiet, introspective film about an affluent family trying to come to grips with a tragedy, and was a thoughtful look into what it means to cope and move on in life. No one could fault its sincerity and intelligence; however, simply put, Raging Bull kicked its well-appointed ass around the block. By the end of the ’80s, Martin Scorsese’s epic boxing requiem was regarded as not only one of the greatest sports films ever made, but also topped polls as the decade’s best film. Powered by Robert De Niro’s stunning performance, Raging Bull was that rare combination of artistry and ferocious filmmaking skill. Nevertheless, Robert Redford also beat Scorsese for Best Director, a cinematic crime if there ever was one. Perhaps it was a little too raw for some palates, but this was truly a case where family values were determined with brawn, not bromid.

After the 1979 victory by Kramer vs. Kramer, this marked back-to-back years that family dramas made off with Oscar. Ordinary People was a quiet, introspective film about an affluent family trying to come to grips with a tragedy, and was a thoughtful look into what it means to cope and move on in life. No one could fault its sincerity and intelligence; however, simply put, Raging Bull kicked its well-appointed ass around the block. By the end of the ’80s, Martin Scorsese’s epic boxing requiem was regarded as not only one of the greatest sports films ever made, but also topped polls as the decade’s best film. Powered by Robert De Niro’s stunning performance, Raging Bull was that rare combination of artistry and ferocious filmmaking skill. Nevertheless, Robert Redford also beat Scorsese for Best Director, a cinematic crime if there ever was one. Perhaps it was a little too raw for some palates, but this was truly a case where family values were determined with brawn, not bromid.

The Year: Best Art Direction 1982

The Verdict: Gandhi

The Appeal: Blade Runner Every so often voters get carried away and coronate a particular film with an euphoric sweep, regardless of whether or not all of the victories are merited. Such was the case with Gandhi, the Best Picture winner that danced a whopping eight times with Oscar. It was dubious enough that it won for its costumes (best sheets?), but copping the art direction/set decoration Oscar over the genius of the futuristic dystopian sets of Los Angeles in Blade Runner was a grievous enough choice to mortify even the Mahatma.

Every so often voters get carried away and coronate a particular film with an euphoric sweep, regardless of whether or not all of the victories are merited. Such was the case with Gandhi, the Best Picture winner that danced a whopping eight times with Oscar. It was dubious enough that it won for its costumes (best sheets?), but copping the art direction/set decoration Oscar over the genius of the futuristic dystopian sets of Los Angeles in Blade Runner was a grievous enough choice to mortify even the Mahatma.

The Year: Best Original Score 1986

The Verdict: ‘Round Midnight

The Appeal: The Mission When it comes to music, Oscar has historically shown worse taste than the American Idol viewers who voted for Taylor Hicks. OK, Three 6 Mafia did up Oscar’s hip quotient a bit, but the list of film songs not even nominated could fill a Hall of Fame, including “New York, New York,” “Knockin’ on Heaven’s Door” and “Stayin’ Alive.” The musical low point in recent times, however, came when Herbie Hancock took home the award for his arrangements of traditional jazz standards in ‘Round Midnight. It’s been estimated that there were approximately six minutes of actual original music for the film, but try explaining that to voters. You certainly don’t have to enlighten Ennio Morricone, whose magnificent composition for The Mission lost in a heinous upset. His soaring combination of choral and world music still stands as probably Morricone’s greatest, but instead just wound up another of the five competitive losses for his remarkable career. Last year, he was finally given an honorary award, which is usually Oscar’s way of saying, “I fucked up. Forgive me.”

When it comes to music, Oscar has historically shown worse taste than the American Idol viewers who voted for Taylor Hicks. OK, Three 6 Mafia did up Oscar’s hip quotient a bit, but the list of film songs not even nominated could fill a Hall of Fame, including “New York, New York,” “Knockin’ on Heaven’s Door” and “Stayin’ Alive.” The musical low point in recent times, however, came when Herbie Hancock took home the award for his arrangements of traditional jazz standards in ‘Round Midnight. It’s been estimated that there were approximately six minutes of actual original music for the film, but try explaining that to voters. You certainly don’t have to enlighten Ennio Morricone, whose magnificent composition for The Mission lost in a heinous upset. His soaring combination of choral and world music still stands as probably Morricone’s greatest, but instead just wound up another of the five competitive losses for his remarkable career. Last year, he was finally given an honorary award, which is usually Oscar’s way of saying, “I fucked up. Forgive me.”

The Year: Best Actress 1989

The Verdict: Jessica Tandy for Driving Miss Daisy

The Appeal: Michelle Pfeiffer for The Fabulous Baker Boys Oscar can be such a sentimental slob. The pervasive logic is that older actors aren’t going to get that many more chances, while their younger rivals will have plenty of opportunities. That’s all well and good, but for the love of Geritol, this race wasn’t even close. Michelle Pfeiffer did a coast-to-coast sweep of every major award not named Oscar (New York Film Critics, Los Angeles Film Critics, Chicago Film Critics, National Board of Review, National Society of Film Critics, Golden Globe). Her dominance was so complete that she probably had to build an extra wing in her home just to house all the hardware. Her performance as Susie Diamond, the tough-talking chanteuse, catapulted her into superstar status and had critics ripping open their thesauruses to find new accolades. Come Oscar time, though, she never had a prayer. Acting icon Jessica Tandy capped a long and illustrious career with her role as the elderly widow in Driving Miss Daisy – engaging work, to be sure, but a rueful reminder that age before beauty isn’t always the way to go. What the hell ever happened to the concept of youth will be served? Almost twenty years later, Pfeiffer is still waiting.

Oscar can be such a sentimental slob. The pervasive logic is that older actors aren’t going to get that many more chances, while their younger rivals will have plenty of opportunities. That’s all well and good, but for the love of Geritol, this race wasn’t even close. Michelle Pfeiffer did a coast-to-coast sweep of every major award not named Oscar (New York Film Critics, Los Angeles Film Critics, Chicago Film Critics, National Board of Review, National Society of Film Critics, Golden Globe). Her dominance was so complete that she probably had to build an extra wing in her home just to house all the hardware. Her performance as Susie Diamond, the tough-talking chanteuse, catapulted her into superstar status and had critics ripping open their thesauruses to find new accolades. Come Oscar time, though, she never had a prayer. Acting icon Jessica Tandy capped a long and illustrious career with her role as the elderly widow in Driving Miss Daisy – engaging work, to be sure, but a rueful reminder that age before beauty isn’t always the way to go. What the hell ever happened to the concept of youth will be served? Almost twenty years later, Pfeiffer is still waiting.

The Year: Best Supporting Actor 1993

The Verdict: Tommy Lee Jones for The Fugitive

The Appeal: Ralph Fiennes for Schindler’s List and Leonardo DiCaprio for What’s Eating Gilbert Grape? No one does grizzled better than Tommy Lee Jones. Whether as a law-enforcement agent or military officer (the usual roles of choice), Jones oozes world-weariness from every pore, and it’s exactly that kind of weathered authority that finally won over Oscar for Jones’ part in The Fugitive. Who says persistence doesn’t pay? The problem was that he was clearly blown out of the park by relative newcomers in both Ralph Fiennes and Leonardo DiCaprio. Appearing in only his third film, Fiennes was the pure embodiment of complex evil as Nazi Amon Goeth in Schindler’s List. His relative obscurity might’ve actually worked against him, as Fiennes was so chilling that voters maybe figured this guy’s just a little too good. DiCaprio escaped from the bowels of TV sitcom hell and, in only his fourth feature, stunned audiences with his heart-rending portrayal of a mentally challenged youth in What’s Eating Gilbert Grape? Oscar is usually a sucker for actors playing handicapped roles, but for some reason passed on DiCaprio. When in doubt, go for the grizzle.

No one does grizzled better than Tommy Lee Jones. Whether as a law-enforcement agent or military officer (the usual roles of choice), Jones oozes world-weariness from every pore, and it’s exactly that kind of weathered authority that finally won over Oscar for Jones’ part in The Fugitive. Who says persistence doesn’t pay? The problem was that he was clearly blown out of the park by relative newcomers in both Ralph Fiennes and Leonardo DiCaprio. Appearing in only his third film, Fiennes was the pure embodiment of complex evil as Nazi Amon Goeth in Schindler’s List. His relative obscurity might’ve actually worked against him, as Fiennes was so chilling that voters maybe figured this guy’s just a little too good. DiCaprio escaped from the bowels of TV sitcom hell and, in only his fourth feature, stunned audiences with his heart-rending portrayal of a mentally challenged youth in What’s Eating Gilbert Grape? Oscar is usually a sucker for actors playing handicapped roles, but for some reason passed on DiCaprio. When in doubt, go for the grizzle.