In the years since, during which he scored Oscar nominations for his performances in The Last Picture Show, Thunderbolt and Lightfoot, Starman and The Contender, Bridges has continued to play music. In 2000, he released an album entitled Be Here Soon, on which he held his own beside such celebrated artists as David Crosby and Michael McDonald.

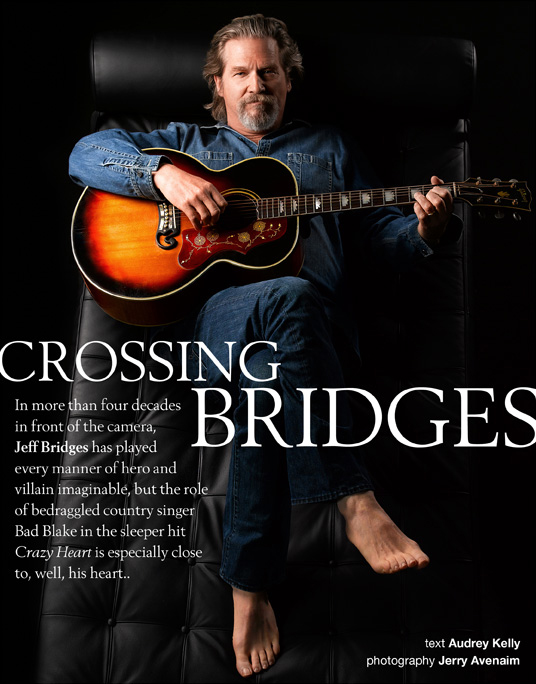

Bridges’ first-hand acquaintance with the delight and despair of making music went a long way toward shaping his widely praised performance as a gifted pianist squandering his talent as a cocktail-lounge entertainer in 1989’s The Fabulous Baker Boys, in which he starred alongside his older brother, Beau. In retrospect, the role of Jack Baker may be seen as a warm-up for arguably the most layered performance of his career — and his fifth Oscar nomination — in Crazy Heart.

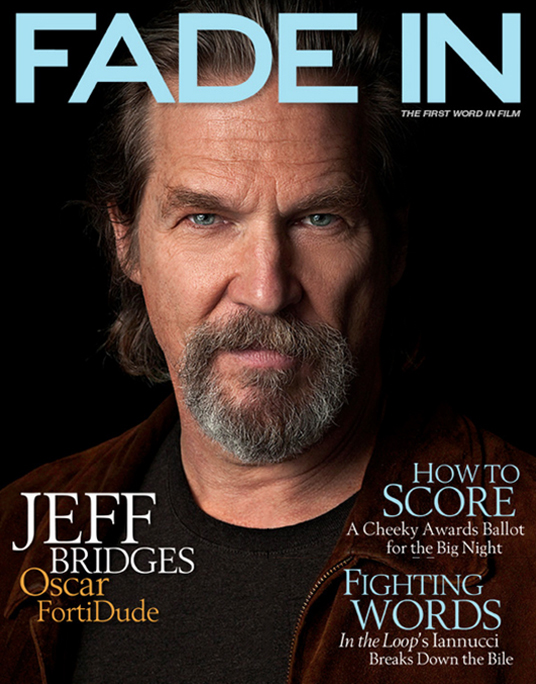

Crazy Heart is the story of a self-destructive country singer who earns a chance at redemption when he forges a bond with a young journalist, played by fellow Oscar nominee Maggie Gyllenhaal. As Bad Blake, Bridges is by turns endearing, infuriating and, ultimately, enthralling — especially when he’s onstage, guitar in hand, pouring a lifetime of reverie and regret into songs written for the film by T-Bone Burnett and Stephen Bruton.

As the son of the late Lloyd Bridges, the admired character actor who became a TV star in the late 1950s as the lead of the nautical drama Sea Hunt, Bridges is one of Hollywood’s true statesmen. (He was, after all, still in diapers when he made his film debut, in the drama The Company She Keeps, being nuzzled by Jane Greer — with whom he reunited more than thirty years later in Against All Odds.) And after having worked with just about every major star, director and producer imaginable, he has fostered boundless goodwill and respect in the industry.

Which is why, if Crazy Heart finally earns Bridges that long elusive Oscar, it will be easy to dismiss the award as largely a sentimental gesture. But those who do so will not only be wrong, they will also be doing a disservice to Bridges the actor and, even more so, to Bridges the musician, whose entire forty-plus years in the business have been leading up to this achievement.

A few weeks before the big night at the Kodak Theatre, Fade In spoke to Bridges about his long career, some of the major milestones along the way, his lifetime love of art and music and his commitment to eradicating hunger.

How are you handling all of this awards attention? I’m filled with a lot of different feelings, a lot of different emotions. It’s kind of a double-edged sword. The upside of it is getting to celebrate and bring attention to a movie I had so much fun making. I loved the way it turned out, and love that people are digging it and going to see it. And that’s largely thanks to our distributor [Fox Searchlight]. It’s rare when all those things fall into place. You can have a good time making the movie, and then it doesn’t come together well — or it comes together well, and then the distributor falls out. With [Crazy Heart], all of those [elements] worked, and it’s a movie that’s all about music, which I love. All of the people I worked with were good friends or became good friends. I got to do this with all of these guys and my wife…that’s fun. Then to get recognition from your peers with all these nominations — you know, guys who do what I do, actors, or critics, people who love the movie so much — to get a nod from those guys feels wonderful.

The other side is, my unappreciated status is blown now. I prefer coming from an un-showing off place, an underdog position. I prefer that rather than having this much attention. You don’t want that. You want to be a blank slate. You want the audience to be able to imagine things. And then having to give speeches… To get up in front of all these people… You can imagine! I’m a human being. I’m trying to read off a teleprompter, but I can’t see the words. What if I forget somebody? And it goes without saying, God forbid if I’m going to call out my director [Scott Cooper], who I love so much, and call him by the wrong name! “And I’d like to thank Chris Cooper…Chris was so wonderful…” I hear my wife yell out, “No, Scott!” All of those fears, they come true. Another good side of that story is that you find out all those things you’re afraid of — they happen, and you survive it. You’ve learned a lesson, but it’s a difficult lesson to learn, that everything is going to be OK. Panicky situations are not my favorite to be in.

My mother, who was an actress as well — she died last year — gave me some good life tips. She said, “Don’t take it too seriously. Remember, have fun.” So I’m trying to follow her directions the best that I can. Part of being an actor is you take your emotions and you jack with them. You blow them up. So I’m real good at getting anxious. I can work that pretty good. So I have to try it the other way.

Do you remember watching your dad, Lloyd Bridges, go through a similar situation? Oh, God! Are you kidding? Are you kidding me?! Sure. Acting’s terrible. I’ve also thought, for a guy who has these kind of feelings that I’m describing, why would you ever put yourself in this disposition to be a performer — a performer who gets performance anxiety? But I’ve learned from other actors, including my father, that anxiety, or that fear of failure — and we’re talking here about the fear of success — that fear is something that all of us who are alive experience to one degree, and actors certainly have it. I thought as a young actor maybe you’d practice enough and you’d do it enough [that] you’d lose that. But having worked with Fredric March and Robert Ryan in the movie The Iceman Cometh, I saw that they still had fear in different ways. They managed to churn out great work, but still had that, and I have that, too. This situation enflames it a little bit. But I’m trying to have fun and not take it too seriously.

Well, you have some interesting metaphysical Alan Watts material up on your incredibly cool website [www.jeffbridges.com], like his reference to the House of Cards, which is all about our lives being predestined. You doing Crazy Heart with T-Bone Burnett and Stephen Bruton at this time in your life, you receiving this recognition, seems like it was all meant to be. Talk about destiny: the birth of this movie started about thirty years ago on Heaven’s Gate. Kris Kristofferson, who was the star of that movie, brought all of his musician friends onboard. T-Bone had a small part playing my housekeeper in the movie. Stephen Bruton played a character in the movie. Lloyd plays a character in the movie. Waldemar Kalinowski, our production designer, had no idea he was going to be a production designer; now he’s one of the top in the business. He was an actor in the movie. And there are some others. A lot of folks who worked on Crazy Heart worked on Heaven’s Gate. We’d jam every night. Ronnie Hawkins is another guy, a friend of Kris’ that he brought, and we would tear up every night after work. Kris didn’t participate too much. He was working every day. We had long periods of time where we weren’t working. So we played and got to know each other musically that way and remained friends all those years. So we would pick up where we left off when we’d see each other.

When I first got the script for Crazy Heart, while it was a good story, it didn’t have any music to it. And I was looking for a story that had music in it. Then I saw T-Bone somewhere, and he asked me about the script, and I said, “Why? Are you interested?” And he said, “Yeah, I’ll do it if you do it.” “Whoa, OK. Let’s go.” Also, I had the bar set pretty high with Fabulous Baker Boys. It had another first-time director, but it also had all of this great music. That set the bar pretty high for me for doing another movie about musicians. So when T-Bone got involved, that changed everything.

“I feel strange. [Am I] gearing up or winding down? They’re both kind of going on at the same time. We’ll see what happens. It’s an interesting assignment…all this adulation or the opportunity isn’t it wonderful? Yeah, it’s wonderful but do you want to ride that; you want to take that and be as famous as you possibly can be? Why do I want any more fame? I don’t want any more fame.”

“I’ve resisted TV [because of my father]. Not wanting to be the same guy over and over and over again. But also I know the work on a TV series is tough, man. I’m open but I can feel resistance. It’d have to be something that would draw me into it. Offer me huge amounts of money, I might do it. I’m not above being tempted by money. Or it could be just working with somebody great or a great story that I would want to tell. Some social issue that I would want to support.”

Did you work with T-Bone and Stephen to come up with the music? How did that collaboration work? We talked extensively about what kind of music Bad would have written, or what kind of music he would have listened to growing up in Fort Worth, Texas — which, it so happens, turned out to be the same town T-Bone and Stephen grew up in. Stephen’s father owned a music store, and he would turn them on to all kinds of great music coming out of Fort Worth, like Ornette Coleman, a great jazz sax player, not just country. So T-Bone made a wonderful timeline [of music] that Bad might have listened to. It was quite eclectic. It had a lot of Bob Dylan on it, and Leonard Cohen. So that list would reflect all Bad’s past influences. Then we started to look at songs of Stephen’s, T-Bone’s and my friend John Goodwin, who I brought to the party, and I had recently gotten into Greg Brown’s music. I wrote some songs, too. Then I went into the studio and demoed some songs that I thought might be considered for the movie. We just threw together all of these songs that already existed to see if any of them might stick and there were a few that did, like Stephen’s “Fallin’ & Flyin’.” The Greg Brown song, “Brand New Angel,” had already been written. Then T-Bone and Stephen started to write together. It’s a great thing that happens; pretty soon the movie starts to dictate what it wants.

You filmed those scenes you had singing with Colin Farrell at a Toby Keith concert, correct? I did.

How long did it take you to set up, shoot and leave? We had too little time, actually. It was kind of exciting trying to get it all done in the short period of time we had.

So you literally were singing in front of 12,000 conservative country fans? Yeah.

And you’re a loyal liberal. [Laughs] Yeah.

That must have been interesting. Gosh, that never even crossed my mind. Isn’t that funny?

Is it true you filmed most of your scenes while battling the flu? No.

Really? Your stand-in, Loyd Catlett, told Entertainment Weekly that you had a bad strain of flu for three weeks of the shoot. My stand-in guy said I had the flu? I might have been struggling with fighting off something but… I don’t remember. He’s probably right. I don’t remember being sick, but I might have been on the edge. Sickness for a part like that, though, is not too bad, because your character’s not feeling too great anyway.

You had some very intimate scenes with Maggie Gyllenhaal. How important is chemistry between costars and how can it influence or improve one’s performance in a movie? It’s everything. That’s the magic of acting. Most stories are about love, one way or another. You’re not getting none. You’re trying to love somebody who loves somebody else. Something going on about love. One of the different things that I’ve discovered in acting is how accessible love is, and how it’s right there. And when you get two people opening their hearts on purpose, it’s amazing how intimate you can get with each other. I’m not talking about screwing or anything. Even a scene with someone like Robin Williams, you know?

When I was filming The Fisher King, I was a little concerned when I first got on set, because I knew Robin was a comedic genius. I had a long scene with him where he’s in a coma. And I’m thinking while I’m trying to give my monologue he’s going to be messing with me. I was concerned about that. But I was pleasantly surprised how Robin approached the work in general. He’s really a serious actor. His comedy kind of comes out of that. He brings into his being this persona that allows him to go out and do all this riffing that he does. But that’s only one facet of who he is as an artist. So when I was doing that scene, for instance, he could have jacked with me, messed with me, he could have fallen asleep because he didn’t have any words. He didn’t do any of that. He was just lying there, wistful, with his eyes closed, doing his part, supporting me. Even talking about it I can feel emotion rising in me about the fear I felt [before doing that scene].

Some actors approach it like they don’t want to be called by the character’s name; they don’t engage too much. That works. I’ve done it that way and had great success that way. The other way is you get to know each other as people as much as you can, and then bring what you discover out of that up to the screen and see if any of that can work. That’s really my approach, and Maggie and Robin are that way as well. The other thing about acting is, it’s this thing where, when you’re doing it with another person, that openness is an element that can add to the work but also this element of playing the characters in the story and being true to that. So if you are playing the queen, and I’m not treating you like the queen, then you’re not a queen. You all have to agree on the script of what you’re doing and support each other in that. That helps bring it up.

Getting back to Robin, he would approach it as a very talented, creative actor, but then there would be times [laughs] when it’d be like four o’clock in the morning, we’d have three more hours [of filming] to go, we’d be working eighteen hours, we’re exhausted and Robin would sense that. He’d plant his feet and go around and start to riff on the cast and the crew and make us laugh. Any other director, especially one that’s working that hard, would say, “Come on, Robin, mind yourself and get back to the work.” But Terry [Gilliam] would do the oddest thing [laughs]. He’d say, “Well, what about Joey?” He would egg Robin on and make him go three times longer than he would have. We’d all be in hysterics. Then, for the remainder of the day’s work, we were energized.

You’ve often said that sometimes you have to be dragged back into taking an acting job. Oh, always, yeah.

Were there any projects over the course of your career that you regret passing on in hindsight? No. I look back on the movies that I’ve done and I’m really pleased with all those stories and all those experiences.

It’s long been rumored that you were considered for, or offered lead roles, in such films and TV shows as 48 Hrs… No.

Miami Vice… No.

Taxi Driver, The Thing, Love Story, Jaws… Jaws? No, no, no.

Big, Heat, An Officer and a Gentleman, The Deer Hunter, Raiders of the Lost Ark… Set the record straight. I wonder how those got started. Unless they’re true, and I’m just not privy to it. That’s possible, too. I remember The Deer Hunter. That actually might be true, because I’ve worked with [director] Mike [Cimino on Thunderbolt and Lightfoot], and it was a weird thing with my agent at the time. He dropped that ball. But the other ones are news to me.

“I used to be upset when I was studying on the set of a movie and all of a sudden a song idea would come up and I’d grab my guitar and I’d start to write. I’d think to myself, ‘Wait, why are you doing this? You should be studying.’ But then I realized once my creative juices are starting to shake up that they all get shook up. So I started to write music. I started to draw.”

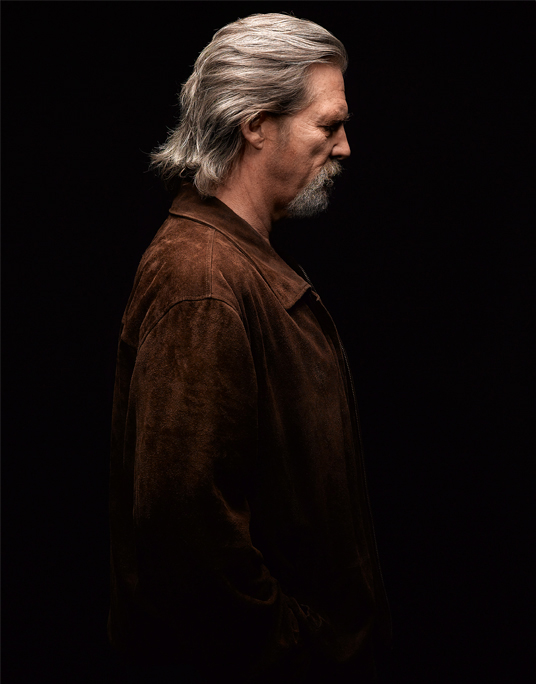

Was there ever a time when you thought of quitting acting altogether and focusing on a completely different career path? Sure, yeah, all the time. My path to the acting thing was started when I was carried on at six months old, right, so not much choice there. My dad would encourage all his kids to get into show business and get little parts in that.

As you’re growing up as a kid, you don’t want to stand out, or have famous parents. You don’t want to be liked for who your parents are. You want to be liked for yourself. You don’t want to be successful because your parents got you a job. I’m a product of nepotism, basically. That’s why I got into acting. And then, as a kid, you don’t want to do what your parents want you to do; it’s just normal. [Laughs] You want to do your own thing. That’s just a natural thing about getting out of the nest. So for a long period, I was making a good living acting, and it was the path of least resistance, but I had a lot of other interests: music and art, other things that I really wanted to do. I did ten films before I decided I wanted to be an actor. I had been nominated for an Academy Award maybe twice, I can’t remember, but still I was thinking, “Maybe I’ll do the music thing.” So the acting was making me resent it because it was taking me away from what I thought I really wanted to do. I could do it, you know. I had been doing it since I was a kid. I was trained to do it. My father was a wonderful, master actor. My mother, my brother, so it was in me, and I could do it, but I had other things I wanted to do.

Often after you make a movie, there’s a certain effort, a certain muscle that’s used that gets exhausted. So a common feeling for me would be, “Oh, God, I don’t ever want to do that again. I’m tired of pretending. I just want to be me. I don’t want to pretend to be somebody else.” That continued on for quite a few films. I still have that feeling occasionally. At the end of a movie, I don’t want to do another one. I want to stop, but I know that feeling is going to pass. But I still have it.

I remember I had just done a film called The Last American Hero, and about a week later my agent called me and said, “You’ve been offered the role of Don Parritt in Iceman Cometh with Robert Ryan and Lee Marvin and Fred March and John Frankenheimer is directing it. Isn’t that great?” I said, “Oh, when does it go?” He said, “They want you to go next week.” “Oh, I’m gonna pass, man.” “You’re gonna pass?!” “Uh, yeah.” “How can you do that?” I said, “Nah, I’m bushed.” So he says, “OK.” I got off the phone, and about five minutes later Lamont Johnson, the director who I had just worked with [on Last American Hero] called me up and he read me the riot act. He said, “You call yourself an actor?” I said, “Well, no, I’m not, really…” He said, “Well, you shouldn’t call yourself an actor, because you’re a dumbass! How can you turn this experience down?” So he hung up on me. And I thought about it, and went, “Huh, this is an interesting time. Maybe I should do a little experiment on myself here. I certainly don’t feel like acting now. I understand that to be a pro you have to do it when you don’t feel like it. I don’t feel like it right now. Maybe I’ll do this as an experiment. Maybe this will be the nail in the coffin of my acting career, or I’ll discover this is something that I really love. So I ended up doing that movie when I didn’t feel like it. And it was a fascinating experience, very unusual. One reason was because, you know, if you’re lucky, you usually get two weeks’ rehearsal, and then you shoot for eight weeks, twelve, whatever, and this was the reverse. We rehearsed for eight weeks and shot for two weeks. So it was eight weeks of working with Fredric March and Robert Ryan, with whom were most of my scenes, and I had an interesting time working on that show, working with those old masters. It was there that I really learned that that fear and anxiety never really goes away. It didn’t go away for those guys, but I could see how they worked with it. Robert Ryan, we were going to do a scene, we’re sitting across a table, and we hear, “OK, we’re ready to go now.” He took his hands off the table, and there were these big puddles of sweat. So I asked him, “Gee, Bob, are you still nervous?” And he said, “Oh, I’d really be scared if I wasn’t scared. That fear is your buddy, and he’s always going to be there, poking at you.” So after that film where I had a really great experience with those guys, I thought, “This is something that I can make my professional career and my other interests can all bring to that.”

One of the things that was so great about Robert Ryan was, he got into acting later in his life, so he had a lot of life experiences he could bring to the work. He could give it real authenticity. Part of my success in Crazy Heart is because I play a musician. All the natural stuff that you can bring to a part, if you can cash in on it, that’s great. In Baker Boys, I played piano. That was kind of cool. Also, working with my brother, we didn’t have to go, “Well, how are we going to show that we’re brothers?” We didn’t mess with that at all. So there have been times when I can use my art.

“We just got a report not too long ago from the Department of Agriculture and 16.7 million kids live in food insecure homes. One in four kids! Food insecure means that there’ll be a night, for instance, Thursday where, ‘Tonight’s the night you’re not eating. You know that!’”

And you’ve successfully combined all of your artistic passions — your illustrations, your photography, your music — on your website. Yeah. Yeah. I used to be upset when I was studying on the set of a movie and all of a sudden a song idea would come up and I’d grab my guitar and I’d start to write. I’d think to myself, “Wait, why are you doing this? You should be studying.” But then I realized once my creative juices are starting to shake up that they all get shook up. So I started to write music. I started to draw.

Started taking behind-the-scenes pictures on set? Yeah. They all have to do with each other.

Speaking of passions, you also helped start the End Hunger Network. Harry Chapin got me involved in the hunger issue; this goes back a long time. I can’t really remember how he got me involved. He put together this thing called The Hunger Project, and he brought to people’s awareness the enormity of the problem. This was world hunger that we’re talking about. And that it didn’t have to be that way. We had enough food. Really what was missing was the political awareness, [to make sure] that they’re paying attention to what we need to do. So he would ask people kind of collectively, “What are you willing to do to further that vision, if this is true, if you can see that we have enough food and you can see that we can do it? Don’t just make a gesture, like, ‘OK I’ve given my hundred bucks, now I’ve done my thing.’ Really look inside and see what you can naturally do to focus that energy to really achieving a world without hunger.” So I said, “That’s interesting.” And I got together with a guy named Monte Factor and Jerry Michaud, and a whole group of actors, and we formed an organization called the End Hunger Network, which was all about interfacing the media, kind of like what we are doing right now with the issue of hunger, and champion this issue. This was thirty, thirty-five years ago. And maybe fifteen or twenty years ago, we wrote all the copy for [Bob Geldof’s] Live Aid concert, and then shifted our focus from world hunger to hunger here in the United States, because all of our safety nets — food stamps, for instance — were not being funded properly, and people were falling through the holes. And now the statistics are just insane. We just got a report not too long ago from the Department of Agriculture that tracks all this stuff, and it was 16.7 million kids live in food-insecure homes. One in four kids! Food-insecure means that there’ll be a night, for instance, Thursday, where, “Tonight’s the night you’re not eating. You know that.” For no one to have food when they need it…you can go on my site and see some of the statistics. And that number 16.7 has gone up thirty-four percent between 2007 and 2008, and it’s getting worse. Soup kitchens are thirty percent more in demand. What we are up to now with the Network is to support this thing called SNAP. Used to be food stamps, but it’s turned into this thing called SNAP. It’s a debit card. It’s much easier and doesn’t have the stigma that food stamps have. People would rather starve than be seen using food stamps. So there’s a movement to promote SNAP, because only two-thirds of the people that are qualified for them are using them. Here in California, it’s only forty-eight percent, so there are fifty-two percent of the people who could be using these that aren’t. So we’re going to be promoting that, and that’s what the End Hunger Network is about.

Having lived through the great years of the ’70s, when many people feel that Hollywood made some of its best movies (and you were in a few of those), how do you look back on that period compared to now? And how has making movies changed? Well that mid-budget movie is hard to find. You’ve got tentpoles and $300 million movies and you’ve got $100,000 movies. It’s kind of an interesting time. Those tentpole movies and the fact that the midrange movies have gone away, it’s making artists come up with new ways of doing things. There’s an upside and a downside to that as well. I have mixed feelings about all these reality shows. Those came out of the writers’ strike. The writers said, “We’re striking,” and the producers said, “OK, well, check this out. [Laughs] We don’t need you guys. We’re going to do this.” So it created this whole other thing, you know? So by taking out that mid-budgeted movie, in a way, we’ve accentuated the lower budget and the higher budget so you get movies like Once. What a great movie, and for 100,000 bucks! And the bang the audiences got for their buck compared to these $200 million movies — I enjoyed Once just as much as any of those.

So that spirit was certainly alive in the ’70s doing those low-budget movies, but they also had that mid-budget, which was kind of nice. You had companies like BBS: Bob [Rafelson], Bert [Schneider] and Steve [Blauner]. They did movies like Five Easy Pieces, Easy Rider, Last Picture Show, King of Marvin Gardens. They were so supportive of artists themselves. Bob Rafelson was the Bob in BBS, and a great director — and some of that spirit I noticed at Fox Searchlight. They support the artist, which is great. It would be great if there were more companies like BBS around.

Companies that take more risks? That take more risks, that support the artists. Those are the kinds of movies that people want to see. Those are the movies I’d like to see, not the big visuals or the films that are based on what was already a success.

But you’re doing a remake right now. You’re currently filming True Grit with the Coen brothers. The movie’s been made before, but they’re not really remaking the movie as much as remaking the book. Charles Portis’ book that it was based on, they’re using as the reference.

What was his role as a consultant for the film? He was brought on to bring some humanity, spiritual direction to the script.

You started your acting career in television. There have been some high-quality shows that have been produced for cable, like Mad Men, The Wire, Breaking Bad and Weeds. Would you ever consider doing television again? It’d be a great way to spend more time at home! One of the things I learned from my father was his frustration at creating a strong persona. My dad did Sea Hunt back in the late ’60s, ’70s, and he pulled that part off so well that people thought he was a skin diver that they gave acting lessons to. So he got a lot of skin diver parts after [playing] Mike Nelson, but he was a classically trained actor who did Shakespeare. He replaced Richard Kiley on Broadway in Man of La Mancha. A very versatile actor. So it was a nice compliment that people thought he was a skin diver, but it created this very strong persona. Kind of like what we were talking about in the very beginning. Eighty, maybe ninety percent of the movie-going experience, a lot of it has to do with what the audience brings into the theatre with them. What they’ve read. What parts they’ve seen. It’s subconscious. You’re not thinking about it, but you’re overlaying it on the image that you see in your mind. So it was hard for people to think of my father as something other than a skin diver, and that was because every night that that show was on, he was in your living room doing that thing again and again and again. And my father must have done eight, nine TV series, you know? To create different personas is the actor’s job. But I don’t think any of them was as strong as Sea Hunt. He had one series called The Lloyd Bridges Show that he had great fun doing because he got to play a different character each week. He played a reporter who would then imagine himself as the subject he was reporting on. That’s what the segment would be about.

So I’ve resisted TV for that reason. Not wanting to be the same guy over and over and over again. But also I know the work that it takes. My father approached it a little bit different than I do. The work on a TV series is tough, man. I didn’t make any hard and fast rules that I wasn’t going to do any television, or anything like that. I’m kind of open, but I can feel resistance. It’d have to be something that would draw me into it. I don’t know what it could be. Offering me huge amounts of money might do it. I’m not above being tempted by money. Or it could be just working with somebody great, or a great story that I would want to tell. Some social issue that I’m behind that I would want to support. So I’m not closed, but kind of resistant.

Directing would be a chance to reinvent yourself. Why haven’t we seen you get behind the camera? Will we ever? [Laughs] I must sound like a lazy guy. I do have some of the Dude in me, you know, kind of lazy. Talk about work — the director, forget about it. That’s a tough job. It’s a much longer job. It goes on for a year, easy. I’m not striking that off the list. That might be kind of fun. These first-time guys like Scott [Cooper], they’ll look to me for things, so I get my ideas other than acting up there. I have a vision of how I see the movie, and if I’m invited to, I’ll express different thoughts on other things besides just my own character. If they’re open to it,

I’ll tell them my ideas. Not that they have to do those ideas, but just if they want to have my [perspective]. So I get to have a little of what directing gives you without having to make the same time commitment, or having my name up there. I feel like I direct and produce a little on some level with each film I do.

You recently turned sixty. Would you say you’re winding down, or just gearing up? That is the deal right now. [Pause] I don’t know. I’m kind of doing both at the same time. Being born and dying at the same time.

Interesting paradox. Yes, but that’s the way it is. That’s the condition. One voice is saying — and it’s not an angry voice, or a threatening voice, but feeling my mortality — “Well, what do you want to do? If you live until ninety, you’ve got thirty years left. Thirty years ago, you were thirty. That doesn’t seem like too long ago, does it? And you notice that it speeds up as you get older?” “Yeah, I’ve noticed that.” “So you’ve got maybe another thirty years left. Maybe forty. If you live to 100, that would be cool. What do you want to do? Because now is the time to think about this. Do you want to do some stuff?” “Yeah, man, I want to do a lot of stuff. I feel this ambition rising.” “Oh, great, great, great.” That other voice is saying, “Don’t give yourself all these assignments. To have the last part of your life feel like you have to do all this shit, you know? You don’t have to achieve anything. You don’t have to prove anything. Relax, man. Let it bubble up, as it will.” “Oh, yeah, thanks.”

So I’ve got both of these voices, and I like this thing to let it bubble up as it will. But I feel strange. Like you say, gearing up or winding down, they’re both kind of going on at the same time. We’ll see what happens. It’s an interesting assignment. It’s very much like your opening theme we were talking about — all this adulation, or the opportunity, isn’t it wonderful? Yeah, it’s wonderful, but do you want to ride that; do you want to take that and be as famous as you possibly can be? Why do I want any more fame? I don’t want any more fame. If I say this, people will ask, “Why? You don’t want people to like you and admire you?” “Yeah, sure.” Like [Sally Field’s] statement: “You like me, you really like me.” What a great, true, honest statement that was. But with both things going on at the same time, the trick is, how do you dance with that, and relax and bring as much joy to it as you can? I want to protect myself. I guess it will work out as it will work out.

Wouldn’t Alan Watts have said, “What’s going to happen is already predetermined”? All you have to do is show up? Alan Watts was a predestined guy? I don’t think he was entirely. I would think Alan would think this, too: Everything is changing. My own personal belief is, destiny and free will are both kind of the same thing, in a weird way. In my mind, both are going on at the same time. It might be destiny to express your will, you know what I mean? [Laughs] You know what I’m saying? And the center of these [House of Cards] is the Joker, right? The Fool who drops the thing and says, “Chris Cooper!” All these foolish things that are opportunities to remind yourself, “Don’t take it so fuckin’ seriously. Lighten up!” So as we talk about gear up or wind down, lighten up [laughs] is what I plan on doing.