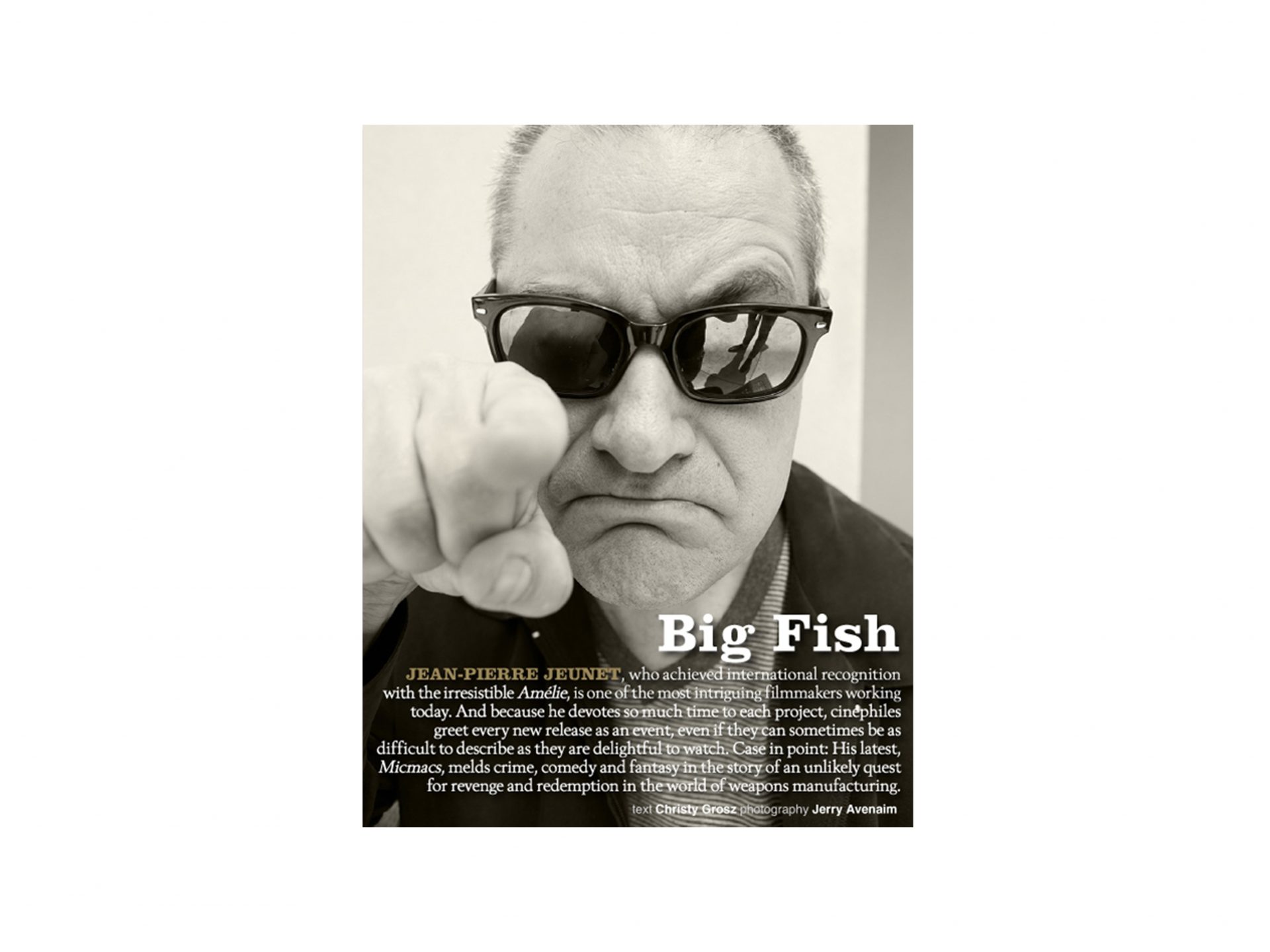

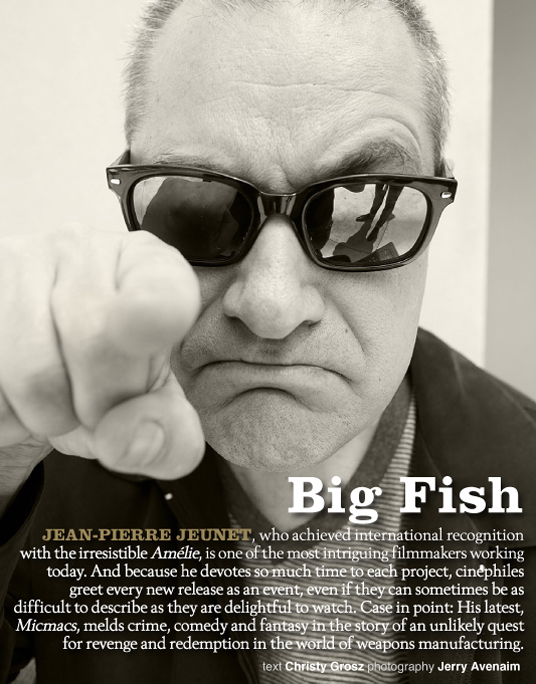

ean-Pierre Jeunet’s credits include a modest six features over two decades, but the self-taught French filmmaker continues to charm audiences who are eager to embrace his imaginative vision and playful style. From his 1991 film Delicatessen to The City of Lost Children (both of which he co-directed with his former creative partner, Marc Caro) to Amélie to A Very Long Engagement, Jeunet has created whimsical characters who find beauty and humor within an ostensibly blighted existence.

ean-Pierre Jeunet’s credits include a modest six features over two decades, but the self-taught French filmmaker continues to charm audiences who are eager to embrace his imaginative vision and playful style. From his 1991 film Delicatessen to The City of Lost Children (both of which he co-directed with his former creative partner, Marc Caro) to Amélie to A Very Long Engagement, Jeunet has created whimsical characters who find beauty and humor within an ostensibly blighted existence.

His latest film, Micmacs, which opened the 53rd San Francisco International Film Festival in April, recalls the colorful, eccentric worlds he has made his signature. Stirring bleak subject matter with fanciful freaks, Micmacs follows Bazil, a man who crafts an elaborate plan to seek revenge on the weapons manufacturers whose handiwork killed his father and left Bazil with a bullet lodged in his brain. With help from a merry band of junk dealers that he meets along the way, Bazil charts a course to take on a pair of powerful corporations in a David-and-Goliath showdown.

Jeunet says the title roughly translates to “shenanigans,” a word he recently learned and gleefully uses to describe the action.

Shortly after the San Francisco screening, Jeunet sat down at a quiet Beverly Hills hotel with Fade In to discuss his love of film, his experiences working in Hollywood and the differences between cinema in America and in France.

What made you decide to focus on the world of arms trading in Micmacs? The film has so much humor in it, and that particular subject doesn’t exactly lend itself to levity. I wanted to make a film for kids, a film for teenagers, a slapstick cartoon — I wanted to put everything I love into this film. And one of my preoccupations, like the war in A Very Long Engagement, was a weapons deal. It’s strange. I thought, “Chaplin made The Great Dictator, Kubrick made Dr. Strangelove, so why not?”

You’ve compared Bazil and the rest of the junkyard gang in the film to Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs, but in some ways they’re almost like superheroes because each has a special power that’s unique unto them. Yeah, very, very little power. [Laughs] It’s like the seven dwarfs: one of them was shy, another one was sleepy, and I tried to get this kind of specific character for each of them, [while] helping the story. Maybe it’s also — I understood this later — a bit of a metaphor for the cinema. Because I need the crew with specific things, like production designer, set designer, to accomplish my film, like [Bazil] accomplishes revenge with his crew.

Going back to the weapons trade, was there any kind of political message you were trying to convey in the film? I don’t like the word “political.” It’s not a scoop to say that weapons are bad. But we made serious work. Even if you’re making a comedy, you have to know what you’re talking about, or instead you feel it’s fake. So we [made it] real with research. We [interviewed] people, retired people, working on the weapons deal. We visited a manufacturer in Belgium that builds arrows going through the tank. We met very interesting people — very nice people, in fact. They have a passion for technology. They don’t want to think about the final destination of the technology. When you say, “But at the end, you kill people, you give suffering and pain,” they say, “We work for the right side. We work for the minister of defense, not the minister of attack. It’s protection.” They protect themselves. They don’t have the hate. It’s just a passion to build something. When they say, “We don’t sell to the bad guys,” they know, of course, the good guys resell the weapons to Africa or wherever.

“I don’t want to say I wasn’t free when I made Alien: Resurrection. In terms of the artistic situation, I was free. But you have to convince people. They have some notes, and you have to try everything. Some times they had very good ideas, but sometimes it was stupid. In France, I have nothing to explain… it’s not like in the U.S.A… Sometimes they say, ‘We don’t like the voiceover.’ And I say, ‘I don’t care. I like it.’ In U.S.A., they don’t like it? You cut it. You know what I mean? It’s a huge difference.”

“I am like a chef. I prepare a good meal for me, and I taste it. ‘Mmm, I think it’s good. Do you want to share it with me? And [if] some critics or people say, ‘No,” then you’re disappointed. But if they say, ‘Yeah, yeah, it’s good.’ Then you are very happy…if they don’t like my film, I can say, ‘I have a fish restaurant. If you don’t like my fish, there is a very good other restaurant across the street. In my restaurant, you get fish.’”

Most of your work could be considered fantasy. Is that a label with which you’re comfortable? No, it’s more poetic, a modified reality. In English, you say “quirky.” I learned this beautiful word. I learned “quirky” and “shenanigans.” It’s a bit like the French films from the 1940s [that] Marcel Carné, the French director, made with Jacques Prévert, for example. The most famous is Children of Paradise, and it was reality, poetic and real, and I try to do a continuation of that.

Colors are so prevalent in your films. How important is color in expressing your vision? I like to modify reality in terms of dialogue, in terms of music, acting. I’m interested in face, and also color. I feel like a painter. Kurosawa used to say that if you take one picture of a film, it has to be like a painting, it has to be beautiful. And that’s the way I try to follow, with a short lens. I make the composition of the frame myself.

Along those same lines, are you interested in making a 3-D film? I want to make a film in 3-D. I heard it’s complicated, not easy to make. But Micmacs could be great in 3-D, just because it’s a fun movie. On the other hand, it’s a paradox, because I would have liked to make this film with a lighter camera to shoot faster and quicker. I am tired to wait for the lighting and the grips.

You’ve said in the past that Amélie represented “film happiness” for you. Do you feel like you have to balance art with commerce, or do you focus solely on the art? You can’t think about that, you think just about you. I am like a chef. I prepare a good meal for me, and I taste it. “Mmm, I think it’s good. Do you want to share with me?” And [if] some critics or people say, “No,” then you’re disappointed. But if they say, “Yeah, yeah, it’s good,” then you are very happy. But the first time, for you, you want to find something beautiful and good for you. If one person is happy, it’s good, but not for the producer. You must make a number of people happy.

That’s how you’ve ended up with such an interesting visual style? Yeah, I like to direct with a strong style. We have two different kinds of director. For example, James Cameron, very good director, or Roman Polanski, or Ang Lee, they change their style for each film. Then you have Tim Burton, or David Lynch, Terry Gilliam — you recognize their style immediately. You can say they make all the time the same thing. When you have a strong style, it’s easier to say that you make the same film all the time. You know what I mean?

Yeah, because there are so many elements that are instantly recognizable as part of the style. But if you appreciate the director, you are very happy. And you know something, if they don’t like my film, I can say, “I have a fish restaurant. If you don’t like fish, there is a very good other restaurant across the street. In my restaurant, you get fish.”

What is the difference between French filmmakers and American filmmakers? There is a huge difference. We have the freedom. I don’t want to say I wasn’t free when I made Alien: Resurrection. In terms of the artistic situation, I was free. But you have to convince people. They have some notes, and you have to try everything. Sometimes they had very good ideas, it wasn’t stupid, but sometimes it was stupid. In France, I have nothing to explain, but I am very professional. I do make some test screenings, too. But it’s not like in the U.S.A. Sometimes they say, “We don’t like the voiceover,” and I say, “I don’t care. I like it.” In U.S.A., [if] they don’t like it? You cut it. You know what I mean? It’s a huge difference.

You mentioned Alien: Resurrection, the fourth installment of the Alien franchise, which you made for Fox in 1997. What were some of the other differences you found in working on such a big-budget film? It’s not a question of money, because the bigger movies are worth the money. Each day, I would tell them, “It’s too much. Work faster, less takes, less shots.” But in terms of artistic direction, I don’t want to say they don’t care, but they were satisfied, no problem. In Hollywood, huge budget, no problem. Everything is so expensive in Hollywood. So many people on the stage, everything is huge. We wanted to shoot some debris on the hair — immediately we had a crew with forty people to shoot some crumbs on the hair. It was a great experience. I met my wife. She’s from the Bay Area. I love to come back to L.A. I spent twenty amazing months here.

“I wanted to put everything I love into [MicMacs]. And one of my preoccupations, like the war in A Very Long Engagement, it was a weapons deal. It’s strange. I thought, ‘Chaplin made The Great Dictator; Kubrick made Dr. Strangelove, so why not?”

Is it true you turned down Hellboy and Harry Potter and the Order of the Phoenix? [Hellboy is] an Internet rumor, an urban legend. Harry Potter? Yes. I had the courage to say no because everything was on the table: the casting, the costume design, the production design. It was an amazing proposition, but I thought life’s too short to spend two years working.

You’ve made six films in close to two decades. Is that because not much interests you, or you’re trying to pace yourself? [Laughs] No, no, I write my scripts, so it’s another job. To find the idea and to write it takes one year. And I’m looking for the money. It’s a long process because I’m very picky in shooting — for production and in the promotion, too, because I lose almost eight months for the promotion. Traveling, speaking with you. During this time, I can’t even think about the next one. I can’t work.

So you don’t really have any downtime in between projects? No, but I love to take my time. I love to write and to direct. I couldn’t direct a project every year. It’s so difficult physically. It’s very tough.

Were you being pressured into making another film quickly after A Very Long Engagement, or is that always dictated by you? I had the proposition to make Life of Pi, and it was a beautiful project. I say a great director has to make a black-and-white movie — I made a short film, an American movie — I made Alien: Resurrection, a big success — and Amélie and a film that never [got ] made.

Does Life of Pi qualify as the film that never got made? Yes, for me. Because Ang Lee is supposed to make the film now, but in a different direction, maybe. The budget seems huge because it’s very complicated to make. But it was two years. I wrote the script and made storyboards, for six months, because I had to build the model for an animation film. With my little camera, I took 500 pictures and we drew everything.

Was it hard to leave it behind after all that work? Not really, because at the end I was so starving to shoot. I could have continued to look for solutions but [instead] I said, “I [have to] leave now. I need to make a film.”