In ten short years Eddie Redmayne has gone from the London stage to the world stage. Along the way, he has inhabited a gallery of characters as varied and dissimilar as one could imagine. His theatre work includes classic Shakespearean roles in U.K. productions of Twelfth Night and Richard II; an acclaimed performance as the gay son of an adulterous father whose mistress would be more at home in a barnyard than a bedroom in Edward Albee’s The Goat; and the portrayal of an inquisitive studio assistant to Abstract Expressionist icon Mark Rothko in John Logan’s Red. His filmography is similarly eclectic: in Savage Grace, he played Julianne Moore’s incestuous, schizophrenic son; in The Yellow Handkerchief he was an itinerant Native American in love with Kristen Stewart; and in Hick he was a pedophile meth addict posing dangers to Blake Lively and Chloe Grace Moretz. Not exactly your garden-variety leading-man resume.

He crept closer to the mainstream with My Week with Marilyn, as the aspiring filmmaker entrusted with watching over Marilyn Monroe (Michelle Williams) during the filming of The Prince and the Showgirl. Now Redmayne is really threatening to blow his penchant for playing troubled souls, earning raves for his role as the lovestruck student revolutionary, Marius, in the phenomenon known as Les Misérables, along with Russell Crowe, Hugh Jackman, Anne Hathaway and Amanda Seyfried.

Although Les Miz may seem like an even more traditional path for the thirty-one-year-old actor to take, it actually represents yet another quantum challenge, for he had never sung in a professional capacity before. After a rigorous audition process, Redmayne came away with the role and is now attracting the type of talk that often results in shiny trophies. Not that that’s anything new to him, having already made room on his mantel for various theatre awards, including the prestigious Olivier in the U.K. and a Tony for his role in the Broadway production of Red.

Born in London, Redmayne got an early taste of the bright lights at the tender age of twelve, when he played Workhouse Boy Number 40 in the Sam Mendes-directed production of Oliver! in the West End. Later, it was off to the elite boarding school Eton, where his classmates included the future king, Prince William. He went on to earn an art history degree from Cambridge, but the lure of the stage proved too alluring. Just two years out of school, he caught the attention of Hollywood when he was cast as Matt Damon’s son in The Good Shepherd, directed by Robert De Niro.

If Redmayne has a guiding principle, it’s his desire to avoid predictability at all costs, and although he has been on the short lists for such mammoth upcoming films as The Amazing Spider-Man 2 and Guardians of the Galaxy, rest assured that once you think you have him figured out, like the chameleon he is, he’ll change. This protean nature has also served him well in brief stints as a Burberry model, and even landed him a spot on Vanity Fair’s International Best Dressed List.

Having literally just arrived in Los Angeles for part of the whirlwind — and worldwide — Les Miz press tour, Redmayne stopped briefly at In-N-Out before arriving at the Fade In photo shoot to introduce his girlfriend, Hannah Bagshawe, to one of America’s best known burgers. Although this side of the business — and certainly the attention surrounding Les Miz — is still new to the actor, he takes it all in good stride. Besides, for a workaholic like him, it’s all part of the process. And based on the success he’s enjoying and the choices he’s making, it’s an evolution that should suit him well for a very long time.

Given that the original novel of Les Misérables was 1,200 pages, the stage musical over three hours, and now the film is nearly two-and–three-quarters hours, can you sum up Les Miz in a brief haiku? Oh, my God. [Laughs] Oh. My. God. Oh, my Christ. I’m the shittiest poet in Christendom. [Laughs] Give me an easier one. Let me think on that. That is the hardest question I’ve ever been asked in my life. Fuck me. I’m now sweating about this interview.

You’re right in the middle of the vortex of publicizing a big film. How do you keep your sanity and balance? Oh, I’m not sure I do. [Laughs] Well, the lovely thing about it is I get to do it with Tom [Hooper]. We did a television thing [Elizabeth I] together eight years ago in Lithuania with Helen Mirren about [Queen] Elizabeth, and since then he’s someone who’s come and seen every play I’ve done, and he’s a friend. And of course, through big films, he’s already been through the ringer with it, so he’s a great one for lending advice. But also, really, there’s something about the fact that it’s the run-up to Christmas, and I always think December is kind of a crazy, bizarre, weird time of year, anyway. I feel really privileged to be a part of it, and the thing that I feel most proud of is having loved this thing since I was a kid, seeing how the audiences are reacting emotionally to it. If this is the part of our job where some actors might go, “Oh, we have to go out and promote this thing.” — how wonderful to be able to promote something that you care about.

Would you have been able to handle this type of attention as well, say, five years ago? That’s really difficult to judge. I’m probably not the person to judge whether I’m handling it well. [Laughs] You probably have to go ask Hannah. Probably not, although I grew up in a family of a lot of brothers who were constantly ribbing and making sure that your feet were firmly planted, rooted ten feet beneath the ground.

“There were weird stunt butterflies on set, [and] while Amanda and I were trying to sing incredibly romantic and impassioned songs, I would be taking it very seriously and didn’t realize the entire crew would be wetting themselves with hysteria for the entire take because the stunt butterfly had come and perched on my hair.”

This journey you’re on started in a trailer in North Carolina with an iPhone. What happened? I was in North Carolina playing a cowboy meth addict in a film called Hick. It was a night shoot. I was in a field. I loved Les Miz as a kid. I heard they were making a film. I was bored, procrastinating in my trailer, and decided that I would try filming myself on my iPhone to send to my agent to show him that I enjoyed singing. He sent that to Eric Fellner at Working Title without me knowing, and that started an audition process that was like a long, aggressive series of American Idol. I got the part. We had seven, eight weeks of rehearsal that involved substantially weaving aspects of Victor Hugo’s book into the screenplay. A full-on, intense three months then occurred, of which I came out at the end knackered. Cut to Alice Tully Hall in New York [a month] ago, and massive fear and excitement, because the world had expectations for this film. There were huge Les Miz fans out there, of which I was one, and the film moved me and I was proud to be part of it.

When you initially heard that the singing would all be done live on set, what was your feeling — abject terror or way cool? We knew it from the outset, so interestingly, that was what the audition process was about. It was about the rigor of not only could the actors perform it, but did you have the vocal stamina to be able to do it? That was a leap of faith for the production team, because I then went into four months’ worth of training, which I can only sort of describe, really, as when you see actors change their bodies for something, this was a process of working on the musculature in the back of your throat and the tongue. The exercises sounded a bit like The King’s Speech exercises. They often weren’t about singing, they were about holding your tongue and making totally random noises. I related to training like doing dialect coaching for a film. I try and do all that technical aspect beforehand in order that when you come on the set, you can just play the thought. And the fact that this was sung, this piece, rather than spoken, made it so that by the time you were on set, the singing aspect was so instinctive that it was just a way of expelling your thoughts.

You’ve spoken in iambic pentameter with Shakespeare, so how did that prepare you? I had done a few Shakespeare plays and had come straight off doing Richard II at the Donmar [Warehouse] in London to do Les Miz. It was interesting that that entire play is in verse, and there’s rhyme often, and this idea that you can have all this florid language, but still the thought has to appear spontaneous. You have to convince an audience that it’s spontaneous thought, even though there’s the artifice that there’s something rhyming two lines later, and that was a challenge I found with Shakespeare, and it was really interesting taking that into Les Miz because it was very helpful.

Outside of doing Oliver! as a kid, and singing in high school, you hadn’t sung professionally. Did everyone wonder where this great voice came from? I really have to thank this guy Mark Meylan, who was my singing teacher on this, because it was a full-on workout. But it was wonderful to reconnect with something that I loved doing as a kid and I had sort of an instinctive interest in when I was younger, to be able to really brush off the cobwebs and start afresh with, that was really wonderful.

How did Tom help you prepare for the big emotionality you had to handle? In the rehearsal process we just had nine weeks, which everyone thinks was a vast amount of time, but in that nine weeks there was a bit of singing, standing up and moving it around a bit, but there was no sort of setting anything in stone. What it really was, was going back to the book and finding detail to weave in. I had a real problem with Marius onstage, in that I always kind of wanted to hit him a bit. Various wonderful characters die on his behalf, and he goes through life sort of bemoaning the state of affairs. There was one line in it, which goes, “Life without Cosette means nothing at all. Would you weep, Cosette, should Marius fall?” And I was like, oh, my God, he’s so indulgent, and on stage it’s fine, because he’s an operatic, romantic type, almost. But I knew that wouldn’t work on film because the scrutiny of the reality is too extreme, and so Tom and I worked really hard on going back to the book and putting in aspects.

Like? The creation of his grandfather coming into things, albeit as a sketch, as a suggestion. Marius came from wealth, and gave up wealth in order to live in poverty and fight for his cause. In the same way that we added the moment where he takes the bucket of gunpowder and threatens to blow up the barricade — that came straight from the book. So he’s a jagged character. Toward the end, where Jean Valjean admits he’s a convict, Marius’s morality can’t deal with that. In the same way that Marius started leaving wealth for his cause, and ends up marrying someone of a class seemingly similar to his, so the idiosyncratic quality and the hypocrisy in him, I found all of that interesting in order that you try and create someone that is a rounded character.

The song “Empty Chairs at Empty Tables” was shot in twenty-one takes, although Tom Hooper was happy after seven. Why did you insist on continuing, and who wound up being right? The expectation of this show having been around for twenty-seven years, and having sixty million people seen it, and everyone having the soundtrack, and myself having grown up listening to Michael Ball sing that song, and all of us having heard these iconic songs — the weight on your shoulders of the audience’s expectation and your own expectation was quite intense. During the filming process you’d come in to work and you’d hear whispers of, “Have you heard Anne’s “I Dreamed a Dream”? It’s spectacular.” I literally witnessed Hugh sing “Bring Him Home” to me, and the days after these were finished, these big songs, Hugh described it like turning up to a new job as the weight of fear that had been lodged on your shoulder was gone. Unfortunately, Tom kept sort of pushing “Empty Chairs at Empty Tables” further and further into the schedule, and then when it came to doing it… In theatre you can go and sort it out the next day if you screw it up, and on film you can’t. So you knew that you had that morning, or that day, to do it, and when you got home in the car, that moment was gone, so the stakes felt high. We had a very closed set, it was just me in a room with three cameras and Tom, and we did it seven or eight times and Tom said he was happy, but I needed to know. Actors are often never content with the work they’ve done, and I knew that six months later I was never going to be happy with the work I’d done, so I needed to know that I kind of bled for it in order to not flagellate myself too much when I saw it. And so I said, “Can we keep going?” [I wanted to use] this process Robert De Niro had worked with me on when we did The Good Shepherd, which was this idea of keeping the camera rolling and putting enough stock in to do a few takes at a time. In emotional scenes, when you get to the end of the scene, and you can reach an emotional climax, you can then feed that back into the top of the scene and start the whole thing over again. Sort of bury that emotion in order to start somewhere more fragile that you can take to a different place. Tom allowed me to do that, and we wound up doing twenty-one takes, and he told me the other day that the twenty-first take was the one he wound up using, so I’m pleased with the system.

When you’re acting while you’re singing, does one take prominence? The four weeks of vocal prep to sort the voice out helped, in that I was never thinking about the singing. What I cared about was the thoughts. I did a thing for PBS and the BBC last year called Birdsong, it was about the First World War, and Philip Martin, who directed it, encouraged us to watch Armadillo and Restrepo, two war documentaries, and there were extraordinary moments in that about when soldiers in Afghanistan hear from their company sergeant that someone’s been killed from their company, and there’s that moment where you’re waiting to hear who it is, because humanly, you don’t want it to be one of your mates. And then, when you hear it’s not, there’s sort of that sense of relief, but then there’s the guilt that still, someone you didn’t know has died, and this idea of survivor guilt, trying to find a contemporary way to relate to it. I found those documentaries incredibly moving, and incredibly enlightening, and [they] made me embarrassed at how little I realized how active a war it was we’re fighting, rather than a passive one. So I tried to fill myself with contemporary things to place the soul.

What did you do to keep the set light? I suppose the more rigorous and emotional the film, quite often the lighter the set. There were karaoke nights, and Amanda Seyfried generally was hilarious. There were weird stunt butterflies on set, [and] while Amanda and I were trying to sing incredibly romantic and impassioned songs, I would be taking it very seriously and didn’t realize the entire crew would be wetting themselves with hysteria for the entire take because the stunt butterfly had come and perched on my hair and sat there gently flirting with the camera for the entire take.

You’re part of the new wave of young British actors that includes Andrew Garfield, Henry Cavill and Jim Sturgess. Is Hollywood actively coming looking for you, or do you still have to come out here to stake your claim? Oh, that’s a good question. While it may feel like it’s sort of overnight, all of those actors you mentioned, we’ve been working for six, seven, eight years in London. Things like Variety and the Hollywood Reporter, for example, will review British plays, and agents will come over to see their clients, and there’s definitely a sense of talent scouting in London, when American agents will come over and see their American clients in plays in the West End. That’s how I was taken on. A gentleman called Josh Lieberman from CAA was staying at the Covent Garden Hotel and came and saw a play I was doing at the Donmar called Hecuba, and this was before I had done anything at all onscreen. The concierge at his hotel told him, “There’s a play on at this great little theatre around the corner, why don’t you go and see it?” He came up to me in the bar afterward, and that’s sort of how all this started.

Did you tip the concierge? [Laughs] I never met the concierge, but I have a lot to thank him for. It’s also interesting in that’s sort of how The Good Shepherd came about, because Amanda Mackey, the casting director, read a review in Variety of The Goat, an Edward Albee play I was doing in London, and it was that review that capitalized her to sort of call me in for a meeting. So I don’t know what the trend in it is, or whether things like mobile phone technology, and although it wasn’t meant to be a full audition, the fact that I sang into my phone and can email it or have meetings with directors via Skype, does make the world smaller.

Do you feel there’s any snobbery from the theatre community in Britain about actors who gravitate more toward film? I don’t think there’s a snobbery, it’s just that we come from such a theatrical tradition that, as an actor in England to be taken seriously, whatever the word “actor” means, you have to satisfy people in both, and prove yourself, because of the greats like Olivier, Gielgud or Alec Guinness, who did manage to do both. I suppose that’s why in England you need to be able to demonstrate the range.

What was most difficult about the transition from stage to film? I started doing stage in London ten years ago, and I don’t think I got anything on screen, either TV or film, for a couple of years, because you have no training. You have no idea what the camera’s seeing. It’s interesting that as the technology gets better, nowadays actors quite often put themselves on tape, so you can learn from your mistakes, or you learn from watching film and seeing what you did wrong. I suppose it’s all just a learning process. There’s definitely a learning curve. I wouldn’t say it was difficult; I actually found it kind of intoxicating, because theatre is what I knew, and I wasn’t particularly well versed in film. So it was a wonderful way of finding a new interest and new passion, while taking your own skills along with it. I found it intriguing rather than difficult.

You’ve said that you’ve found fear to be inspiring. How? Because generally I’ve found that the work that I’ve done that’s outside of my comfort zone, when I have to leap further from myself, I find I tend to do more interesting work, and I find the process more disconcerting, but also more exhilarating. So it’s often the parts I feel like I’ve been pushed on the most as an actor, when I’m cast in something that feels entirely inappropriate, but someone has offered it to me, some mad person has a bit of blind faith in me taking that. Like I did a film called The Yellow Handkerchief, where I played an adopted Native American, or Hick or Savage Grace, playing this incestuous kid. The things where it feels really outside of my comfort zone are the more intriguing ones for me, and certainly Les Miz felt like the extremity of that because it was a musical.

“Everything’s been a fight for me from the start, although I’ve been very lucky to be employed a lot since I started. You’re always fighting to get into a room that people won’t let you into. For instance, with Savage Grace, the financing fell through, and I had to fight tooth and nail, and it ended up being Julianne Moore that supported me on that because the financier wouldn’t. But it’s good, because you feel you’ve earned it.”

“I’m becoming more interested in directing. I have such admiration for film directors because they have to be the masters of many arts, there’s this sort of polymath quality to what they do, and you need to be schooled in all those things to be a really, true great director.”

You won a Tony for Red and made a very interesting comment in your acceptance speech about how the arts matter. Yet the film industry is driven by the bottom line. How do you reconcile the two? I reconcile it, I suppose, by trying to shake up what I do, and to be able to not place myself in a pigeonhole as far as the type of work that’ll I do, whether it’s small independent films that are interesting, or working with actors or directors. Savage Grace is a film I did with Julianne Moore, directed by Tom Kalin and produced by Killer Films, which had a really strong, extraordinary story, and it was an incredibly stylized piece, and it was Tom Kalin’s film. I love being part of a director’s vision. Whatever people think of it, it’s definitely someone’s take on the world. And interestingly, Tom Hooper is the same, and what’s extraordinary, though, is seeing a piece the scale of Les Miz with the studio absolutely having a bottom line with a lot of money involved, but you still felt you were part of one person’s vision. That’s, I suppose, when I enjoy my job the most — when you’re a collaborator, but you’re under the vision of someone with a strong take.

In the U.K. you do mainly classical roles, while here in the States you play very troubled souls. Why the dichotomy? The dichotomy was catalyzed by the first proper theatre job I ever got, which was an Edward Albee play called The Goat, playing a young man who comes from a very liberal family and his parents are seemingly very happily married. Then it transpires that his father is having an affair with someone called Sylvia, and it turns out that Sylvia is a goat. And the son is gay and is going through problems in his own life and trying to reconcile the fact that his dad is a goat-fucker. Weirdly, it was that job, which again, rather than leaving university and going straight into doing English period drama…it was playing that character, followed by Savage Grace, followed by Yellow Handkerchief and The Good Shepherd, so I don’t know what people see you as to begin with. I remember certainly with Hick, that Trevor Moretz and Derick Martini, one of the producers and the director of Hick, saw that I done Savage Grace, and it was probably like, “The guy’s willing to do incest, so he’s probably okay with being a meth-head.”

Are you worried about stereotyping here? Not really, because I find them all so different from each other. I find them all meaty, and things you can really get your teeth into. I’m totally aware of the fact that My Week with Marilyn and Les Miz are hitting a larger audience than I had before, and so that’s probably what you get known for, but for myself, and where keeping a colorful life is concerned, I like being able to shake it up.

Have you ever felt any pressure to take jobs? There’s always pressure to do things. The thing about film is no one knows quite how it’s going to turn out. There is always something organic that happens or doesn’t happen with a film. I’ve done films where I felt the cast and script were great, and I felt I was so proud to be part of, and then something happens and the film doesn’t quite work. Or there are things that you question, and then it ends up being much better than you assumed. I always feel film is such a massive gamble, and you’re much less in control as an actor, whereas on stage, perhaps you have more control over what you’re doing. But then again, that’s something I find intriguing.

Have you ever done something that you’ve regretted? [Laughs] Plenty, but I’m not going to list it.

What kind of roles are you being offered now? Sort of a hybrid, I suppose, to all of these things. But as it always is, the ones that you want are the ones you have to go and change people’s opinions from before, and that’s what I find interesting. Everything’s been a fight for me from the start, although I’ve been very lucky to be employed a lot since I started. You’re always fighting to get into a room that people won’t let you into. For instance, with Savage Grace, the financing fell through, and I had to fight tooth and nail, and it ended up being Julianne Moore that supported me on that because the financier wouldn’t. But it’s good, because you feel you’ve earned it. It was the same with Les Miz. We were all put through the most rigorous process of auditioning, but the great leveler was that everyone from Russell, Hugh, Annie, Amanda, Samantha — we all sort of arrived having all gone through this thing. The whole process felt completely new. What was again wonderful about this job, more than any, was the sense of ensemble, because we were all bound by that unknowing. I’d go and ask Hugh for advice, or Russell for advice, and if someone discovered something through their day’s filming, they’d go and share it with us.

What was the best advice you got during filming, and who gave it? Hmmm… [Pause] I remember Annie talking in rehearsal about this idea. She’d been having singing lessons for a while in which part of the thing was to be able to sustain a strength in your vocal chord, to sing loudly and passionately but without contorting your face. So it was one thing to get your voice to a place where you could sing operatically, but would that hold a close-up, or would it force Tom to have to cut out of it? That was a great tip because it was then weeks working with a singing teacher, standing in front of a mirror and working out what your face would do. While it sounds very technical, it was something we had to work hard on, because Tom ideally wanted these songs to play through, didn’t want to have to cut out.

Having met with great success in the last ten years, how do you feel you’ve grown over that period? I really feel like the past ten years has gone from fantasy to this thing you’re sort of living. But of course, with each job that you do, the level, the game, gets raised and you keep aspiring higher. I’m so curious to see what the next ten years holds.

What’s your ten-year plan? I genuinely don’t have one. Even with Richard II, I hadn’t done a Shakespeare play for ten years since my first professional job, and it took [former Donmar Warehouse artistic director] Michael Grandage to go, “Right, Eddie, I want you to play Richard II,” and I had to go, “Oh, really? Okay.” I pursued Les Miz because I knew something inside me had loved it since I was younger and had ruminated on that piece for years. I’m becoming more interested in directing. I have such admiration for film directors because they have to be the masters of many arts, there’s this sort of polymath quality to what they do, and you need to be schooled in all those things to be a really, true great director. I try by osmosis to glean moments of that from different people on different film sets, so I would love at some point to direct, but I don’t think that will be anytime soon. I’ve got a lot of learning to do.

Name some of the directors you simply have to work with. Pawel Pawlikowski, who did My Summer Of Love. I thought that film was extraordinary, and I’ve heard his process is fascinating. I would love to work with Christopher Nolan. I remember auditioning for Funny Games with Michael Haneke — I’d love to work with him. These are total dreams, I could keep going. The Coen Brothers. I’m trying to think of the films…oh, Derek Cianfrance, who did Blue Valentine.

How did De Niro’s approach as a director differ from what you expected? What’s interesting about Robert De Niro is that it’s all in the moments of what he chooses, the note he chooses to give you. It’s often not continual notes between takes, it’s something physical, or an indication that he’ll give to you from behind the camera. It’s also about giving you the freedom, doing take after take after take, in order to relax you into playing with it. I don’t know, but it’s the way he likes to act as well. It’s searching to look back on that memory because it was so early in my career. I was so fueled with fear then, I was so excited to have got this part with such an extraordinary cast and such an interesting subject matter. It’s weird; it’s almost like a blur, the memory of it, because it was so overwhelming.

“It was weeks working with a singing teacher, standing in front of a mirror and working out what your face would do. While it sounds very technical, it was something we had to work hard on, because Tom [Hooper] ideally wanted these songs to play through, didn’t want to have to cut out.”

What do you remember from your experience of working on My Week with Marilyn? I suppose what I remember from that experience was the sense of, in some ways, “No acting required.” What I mean by that is Michelle [Williams] was an American film actress coming into work in Pinewood, in the studios we shot in. Michelle was in Marilyn Monroe’s dressing room, the British cast was Sir Kenneth Branagh playing Sir Laurence Olivier, Dame Judi Dench, who is renowned for being the kindest woman in the world, but with an extraordinary spark and caprice to her that is exactly how history seems to describe [her character] Dame Sybil Thorndike. Across the board, and for me as a young British actor getting to work with a different knight of the realm, my eyes were kind of glazed and open, in the same way that they all had a theatrical background, and Michelle came from more of an American film background, and how those worlds intermingled. There were bizarre things on that film, like that I went to the same school that my character, Colin Clark, did. There was a very odd moment where, in the film, Colin takes Marilyn around his school, Eton, and I was taking Michelle around Eton, and there were all these kids coming up. So I say no acting required because there was so much that involved sort of playing a version of myself, but I found that weirdly challenging. As I was saying before, I find it easier to jump to places that are more complicated. I felt that his role was to be a cipher, the eyes through which the audience was viewing this scenario. That, in itself, came with complications.

Do you consider yourself a young or old soul? [Laughs] Think it depends on the day. Sometimes I feel like there’s sort of this Peter Pan syndrome being an actor, particularly if you play younger than you are, which generally I have been. The interesting thing about being an actor is, on your first-ever film you’re working with veterans, so you have to grow up pretty quickly. It’s a weird anomaly. I guess I’m a bit of both. [Laughs] Maybe I’m a middle-aged soul.

What scares you the most, either personally or professionally? Professionally, what scares you the most is that you feel possibly so lucky to do something that you really care about, but because you’ve had no formal training, it’s like you’ve never officially been allowed to do it, so there’s this sort of paranoia in the bottom of your stomach that it can all be taken away, which it can. And that you’re living on the verge of sort of being a bit of a fraud; but that’s pretty standard actor neurosis. And personally, I’d say learning to find some sort of mental contentment while living a life that oscillates so much.

When you’re not working, what do you like to do? I love going to the theatre. I studied art history at university, so I go to lots of galleries. I play sports, a bit of tennis. And I kind of play the piano — not very well, but I enjoy it.

Are most of your close friends in the acting community? I have a collection of about four or five friends who are close, close mates of mine who are actors, and we’ve grown up together and been working together in London and the States. And then my other mates are old school friends, so it’s about half and half.

Why do you think so many people in the arts can only relate to others in the same profession? It’s such an odd profession, acting, that has such wonderful benefits of wealth — and I don’t mean financial wealth, but sort of artistic wealth. All these weird rhythms make it generally quite difficult for people outside of it to understand.

What are the pitfalls of stardom that you’ve noticed and keep telling yourself you must avoid? I suppose the pitfalls are to let the noise of people, of too many yes men, pollute your focus upon the job and the storytelling. Acting is one of those industries where art and commerce meet, and it can be a difficult one to navigate, but often there are people telling you one thing, but you should just make sure you follow your own instincts.

We haven’t read about you having fights in bars or appearing in the tabloids. How have you been able to avoid all that? [Laughs] I’m not a massive bar-brawling type just yet. I feel that from watching my friends who have to navigate these things, they can choose to not be seen. It’s just about how you choose to lead your life.

You’ve worked eighteen months straight without a break, right? Yessss.

Will you be taking a vacation anytime soon, or do you feel you might lose momentum? Do you know n months straight. I worked eighteen months until Les Miz finished. I’d gone from Marilyn to Birdsong to Richard II to Les Miz, and kind of got spat out at the end and felt like I was worried that I was just replaying tricks. I didn’t feel like I was living. So I’ve taken a couple of months off and asked my agents to send really interesting work, stuff that I probably can’t attain, but just to really read the best of what is out in the world. I’ve enjoyed that time, and I’m ready to take Christmas off and then to start again, but I always love a holiday. I’ve never done a press thing like this. The most important thing is to not read your schedule!

Other than that, what’s the hardest part about your job? I suppose it’s the thing that’s weirdly both the toughest and the most exciting, which is the nomadic side of it. The fact that you don’t have any sense of constancy is pretty unheard of, and you can go from working in London for a few months to then being in New Orleans to New York. And I love that gypsy sort of aspect to it, to a certain extent, but then sometimes you kind of wish you had more of a sense of place.

So, no desire to make a seismic shift and move to L.A.? Don’t think so, no. I did a play in New York for six months, and then a pilot there, and I’ve worked here and lived here for a while, but my base is London. It’s home there. There’s a great line in My Week with Marilyn where Kenneth Branagh, as Olivier, says to Colin, “Are you happy you joined the circus?” And it does feel like that. You feel like a gypsy nomad, but I get off on the variety of the life.

stylist Lee Harris groomer Kim Verbeck

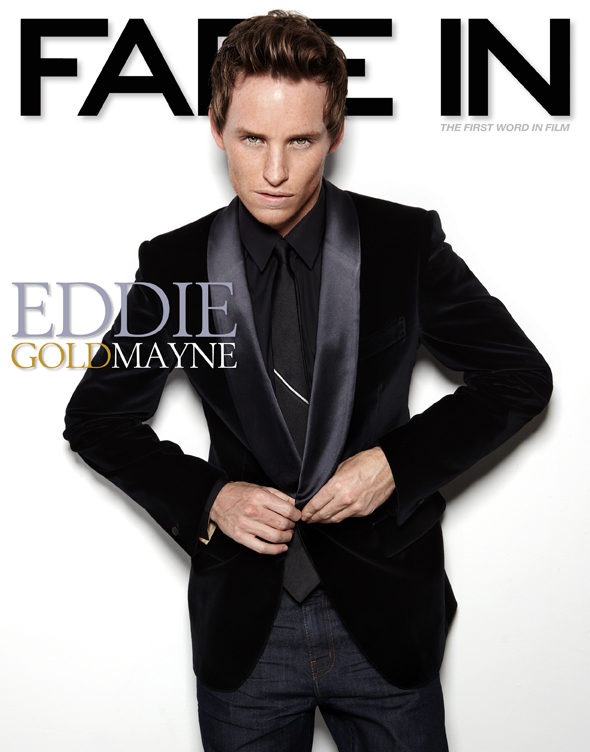

cover: Velvet Tuxedo Jacket: Saint Laurent Jeans: J Brand Black Shirt: Burberry Tie: Rag and Bone

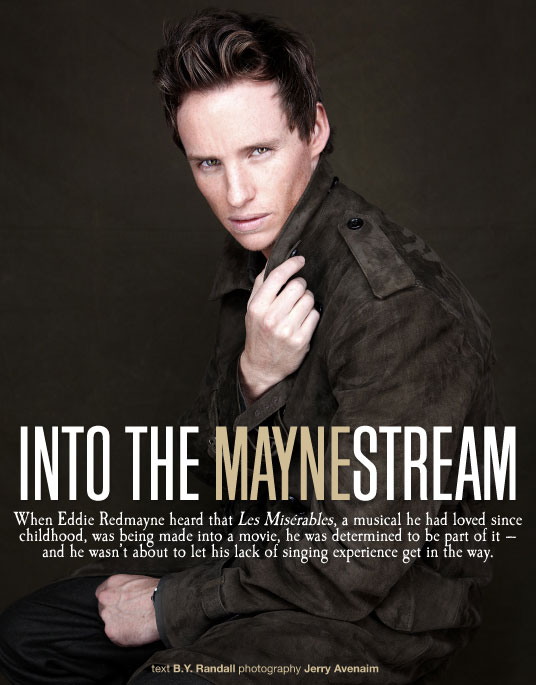

Suede Trench Coat, Trousers: Ralph Lauren Purple Label

Velvet Tuxedo Jacket: Saint Laurent Black Shirt: Burberry Tie: Rag and Bone

Plaid Wool Flannel Vest, Trousers: Ralph Lauren Purple Label Lilirary Shirt: Ralph Lauren Purple Label Tie: J. Crew

Denim Shirt: Dolce and Gabbana Wool Trousers: All Saints Spitalfield Boots: All Saints Spitalfield

Leather/Wool Jersey Jacket: Bottega Veneta Jeans: J Brand Boots: All Saints Spitalfield

Pique Polo Shirt: All Saints Spitalfield