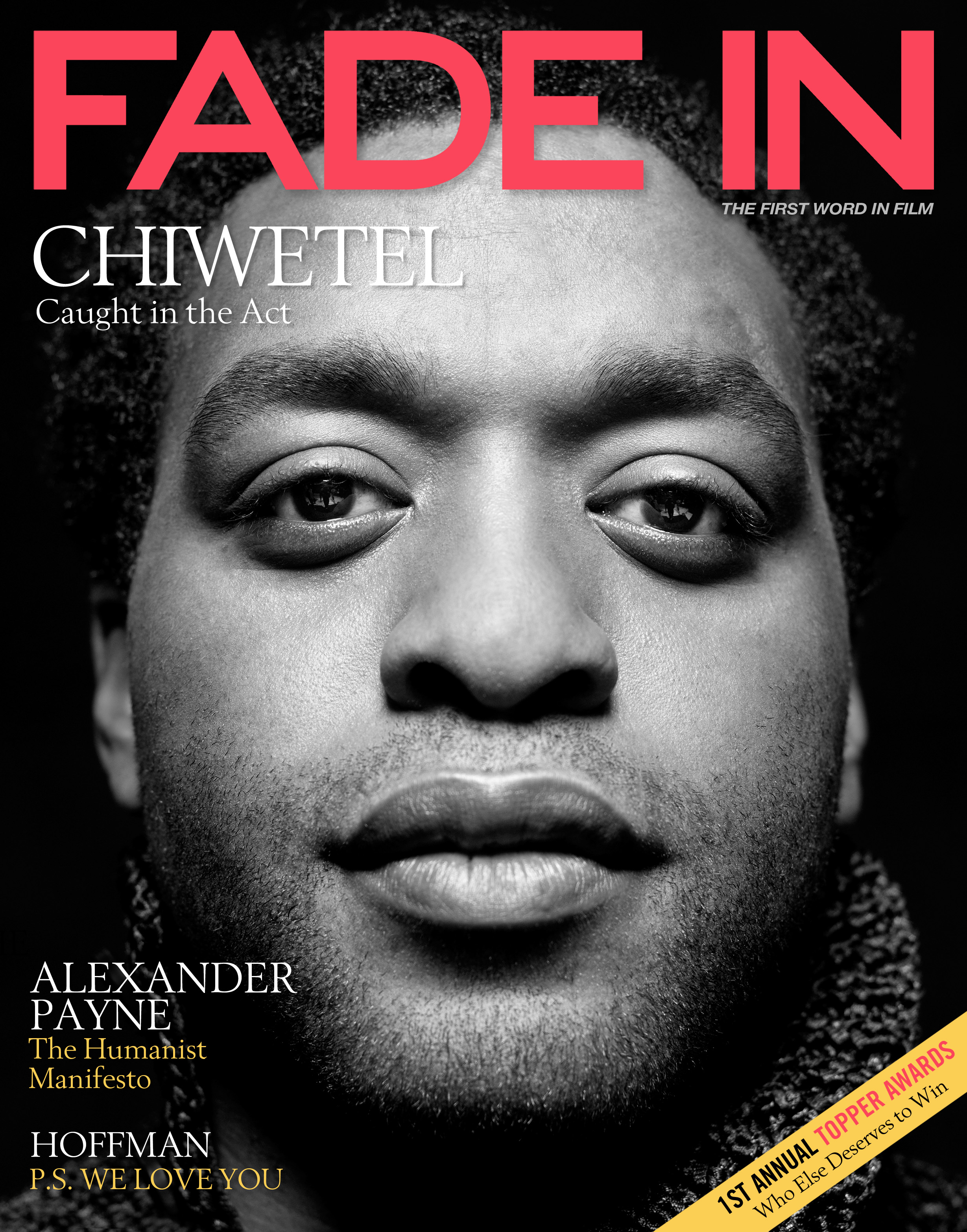

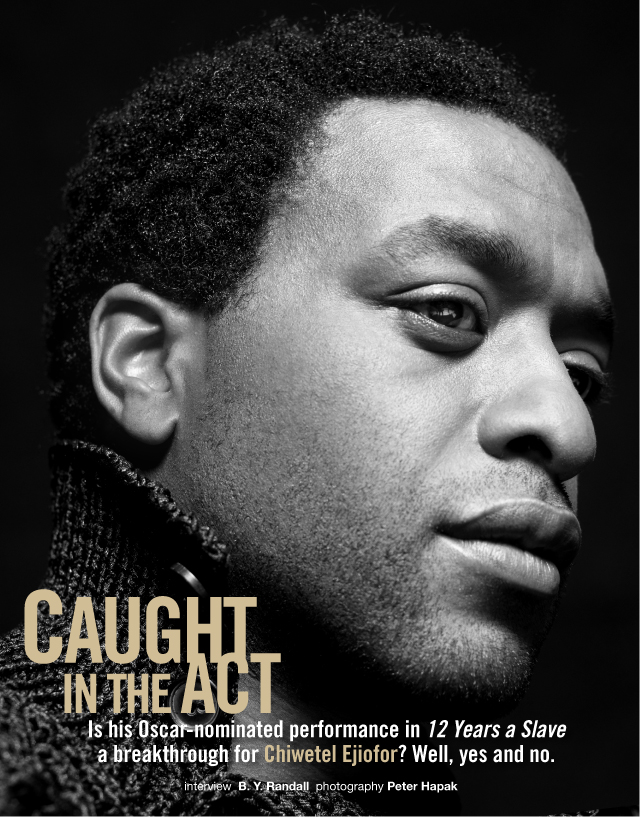

or someone who says he never chose to be an actor — and still hasn’t decided officially — Chiwetel Ejiofor is bluffing his way through a remarkable career. Then again, he once said he has been acting as long as he has been sentient, so perhaps his steady rise over the past decade, which reached a high point this year with a Best Actor Oscar nomination for his devastating performance in 12 Years a Slave, isn’t such a surprise after all.

or someone who says he never chose to be an actor — and still hasn’t decided officially — Chiwetel Ejiofor is bluffing his way through a remarkable career. Then again, he once said he has been acting as long as he has been sentient, so perhaps his steady rise over the past decade, which reached a high point this year with a Best Actor Oscar nomination for his devastating performance in 12 Years a Slave, isn’t such a surprise after all.In the film, directed by fellow Englishman Steve McQueen, Ejiofor stars as Solomon Northup, a free-born African-American from New York state on whose 1853 memoir it is based. The cruelty and violence he witnesses and experiences after he is kidnapped and sold into slavery before ultimately regaining his freedom (through the intervention of a Canadian carpenter and abolitionist played by Brad Pitt, who also co-produced) are difficult to watch and impossible to forget. The film has received a total of nine Oscar nods, although awards themselves are nothing new to Ejiofor, starting with the close to two dozen citations he’s already gotten from various critical groups for his work in Slave.

Those will be keeping company with his just won BAFTA (Britain’s equivalent to the Oscar) for Best Actor in Slave, 2007 Independent Spirit Award for Supporting Male in Talk To Me, a 2002 British Independent Film Award for Dirty Pretty Things, and the Olivier for his 2007 theatrical performance of Othello, just to name a few. Add to that being the recipient of an OBE (Order of the British Empire), the prestigious decoration from royalty given for his services to drama, and his shelf must be buckling under the weight of all the accolades he’s amassed so far.

Although some journalists have hailed Slave as a breakthrough for Ejiofor, he is far from a newcomer. Indeed, over the past ten years he has made a bevy of films and TV movies for directors including Spike Lee (She Hate Me and Inside Man), Woody Allen (Melinda and Melinda), Tom Hooper (Red Dust), Ridley Scott (American Gangster), Alfonso Cuaron (Children of Men), David Mamet (Redbelt and Phil Spector), Roland Emmerich (2012) and Philip Noyce (Salt).

This nonstop pace was sparked by Ejiofor’s intensely solemn performance as a morally conflicted immigrant in the 2002 release Dirty Pretty Things, an absorbing mix of social drama, suspense thriller and star-crossed romance set in modern-day London, directed by Stephen Frears. Next came a supporting role as Keira Knightley’s financée in the hit rom-com Love Actually, and Hollywood beckoned.

By that time, however, Ejiofor, the London-born son of Nigerian parents (and whose younger sister, Zain Asher, is a CNN financial reporter), was already an award-winning theater veteran in the U.K., and had got an early taste of the big time when, as a nineteen-year-old drama student, Steven Spielberg cast him in Amistad. Which is not to say that he has become jaded in the years since, or takes any of his achievements for granted. Instead, he has somewhat miraculously remained as earnest, thoughtful and gently self-deprecating as he was when he was just starting out.

In at least one sense, the tyro label applies – after trying his hand with a pair of short films – he’s currently planning to direct his first feature, The Boy Who Harnessed the Wind. But paradoxically for someone who has appeared in more than twenty movies, he says he is still finding his way as a performer.

Imagine what he’ll accomplish if he decides to make a go of this acting thing.

Congrats on making history at the Producers Guild Awards when 12 Years a Slave tied with Gravity for the Darryl F. Zanuck Award, the year’s top feature, and the first tie ever. What was going on at your table while waiting for the makers of Gravity to finish their speeches, and the other winner had yet to be announced? Just a lot of fevered whispering. I didn’t know whether they were doing them in alphabetical order. Then I was working out the order of everything that comes after G, although sometimes they use the number and sometimes they use the letter for our film.

What have you gleaned from all of this awards attention? It’s quite fevered and it’s vacillating, and it is, in the end, still, for all the push and pull of all the particular movies, it is still a celebration of cinema and television and creativity. That, still, right at its heart, is this actual community. It really gets driven home when you go to the same hotels, the same ballrooms and the same places for different events night after night and see a lot of the same people. It ends up driving home this real sense of a creative community, that this sort of guise of competition is just to meld people together at this event, and actually people start to engage in talking about loving and making films and really great television.

But you’ve finished only the first leg, which was getting to the nomination. Now there’s a whole second half. What do you need to summon up the resolve to make it through the next phase? I will be skipping out on the second half because I have to go to work. I’m shooting a film in New Zealand, and so I leave tomorrow.

But you’re going to miss all the parties! [Laughs] Exactly, yeah. At some point you’ve got to get back to work.

So you’re basically out of the loop until Oscar night. Yeah, exactly, I come back in March.

Where were you when the Academy Award nominations were announced? I was sick, actually. I was in bed, and I had just come down with something. There’s something going around at awards season. All those people crammed together in one room.

“

Were you in L.A.? Yeah, I was fast asleep. Then I had that sort of internal wakeup call that you get sometimes. About 5:20 a.m. I was wide awake and went down and looked at the live feed on the computer. And then the calls and texts started coming. My mother was clearly hovering over the speed dial.

12 Years just opened in the U.K. What’s the comparative reaction been to it here Stateside, and have critics there analyzed or picked up different things then they did here? Well, it’s been received incredibly well in London, not just critically, but also at the box office as well. I believe it’s number one in the U.K. I don’t know what the distinctions are, really. I don’t know if there are lots of distinctions. People are very engaged with the film, and engaged with Solomon Northup, and the extraordinary characters. There’s also an appetite in England to start to deal with, and to talk about more explicitly, the Trans-Atlantic slave trade, and what happened, and how it affected these kind of extraordinary British cities that everybody knows and loves, but that were all built through slavery — Bristol, Bath, Liverpool. It’s starting to engage with the history of that, and the accurate history of that, and people are talking about that, as well, and observing it as a kind of historical piece that happened in America, and understanding the parallels drawn were all over Europe, as well.

Many have referred to 12 Years as a film about slavery and race. Steve McQueen has said that, to him, it’s a film about love. How would you describe it? I would describe it in those terms. Solomon Northup is a man just trying to get back to his family, and armed with that desire, he’s able to withstand one of the most brutal systems ever created in the history of mankind. So in that sense, it is about love, and it’s about humanity. Furthermore, at its heart, it’s a film about human respect and engaging about what that means, about what human dignity is. We’re very much in a world, in some ways more so, with these incredible disparities. It’s always a good thing to engage people in a conversation about human respect, and that’s how I’d categorize the film that talks to that.

Some conservatives have chosen not to see the film because they do not want to be reminded of a terrible time in history. Others have chosen not to see it because of the violence. What would you say to those people? There’s no obligation to see anything. Everyone is a free individual, you know. Thank God. Nobody is forced to see films. The film has extraordinary merit, and I don’t think it’s particularly violent in comparison to what’s out there in the market. There’s five or six acts of violence in the movie, all of them very tastefully done. But they had to be there, because that’s the nature of the slave trade and slavery, and you can’t really make a film about slavery without there being elements of violence, because it’d do a massive disservice to everybody who went through it, and the psychological and physical impact of what occurred, as well as a disservice to Solomon Northup and also his descendants. So of course there’s going to be some elements of violence in the film. Steve has done incredibly well in judging how to do that in a limited fashion, but to still maintain its impact. Kind of like Spielberg did with Jaws. You don’t see the shark very often, but you always feel its presence — it’s there. But that’s basic filmmaking, and that’s how I’d address the violence issue. If your ideas about not seeing the film are more ideological, in a way, everybody’s free to make their own decision about that. It deserves to be seen. Solomon Northup is an American hero, and his story is one for the ages, and one to inspire, I hope, generations of people, but everybody is free to make their own choice.

There was also controversy surrounding the Italian posters for 12 Years featuring a huge image of Brad Pitt and a much smaller picture of you, and it was said Lupita Nyong’o, who plays the tortured slave Patsey, skipped the premiere in protest. What was your take on it, and was it in protest? No, no, of course not. It was Christmastime and we were all trying to get back to our families. I wanted to go, but then I had family commitments, so I had to wave the festival off, and I decided to take the time with the family, as did Lupita. There’s absolutely no reaction to anything to what happened with the poster, of course not, that’s being ridiculous. I don’t think anybody cared that much in terms of the cast. We have this extraordinary story, this extraordinary man and we wanted to tell his story. Obviously, there was, in terms of the poster I suppose, an overenthusiastic marketing campaign perhaps that wanted to promote the most famous names in the film, and maybe it just seemed a little out of keeping with the nature of the film itself. But I certainly didn’t take it as a slight, and I know Lupita didn’t, and the connection to how I, or anyone else with the film, didn’t make it to the festival, it was just a vacation.

So it was just the press trying to gin up controversy? It was maybe the press just seeing two plus two, and putting together a cocktail and coming up with eight. Lupita wasn’t able to make it, this slightly fake controversy happened at the same time, and people put it together and came up with whatever. But there’s absolutely zero correlation to make the decision to not go to Capri [because of] the poster.

You shot 12 Years in twenty-five days. From an actor’s standpoint, what were the pros and cons of working at that pace versus other films you’ve worked on? And was there ever a moment when you had to push back? Well, it was thirty-five, not twenty-five, and it was very quick. The thing I didn’t realize in doing it [was that] obviously we were all working at a a incredibly high pace and intensity, and it felt likethe correct period of time to do that, actually, because everybody who was going through the process in the long haul could give of themselves 100 percent over that period of time.

A longer shoot with this material would’ve been quite harder to sustain. The way that Steve shoots, as well, is very advantageous to the fact that we had a limited amount of time, because he really knows what he wants. He doesn’t do a lot of coverage, so he’s not trying to cover every conceivable angle and then put it together in the editing room. He’s shooting very sparingly, which means that the actors can conserve energy, and there’s a very limited amount of waste, and everybody is able to focus on one or two beats, one or two camera angles. That is, in terms of design, in terms of acting obviously, and background, and everybody [can] be very focused on looking from one angle at a certain scene. In the end, even though it was a very tight amount of time, it didn’t feel like we were short of time. There was always an allowance made for the actors to be able to articulate if [they] wanted to do it again, if [they] wanted to rehearse, if [they] wanted to walk around the park. There was always time and space to achieve everything, which comes from Steve’s bold decisions of his shot selections.

The movie that got you noticed in Hollywood was 2002’s Dirty Pretty Things. How important was that movie to your career, and how did it change people’s awareness of you and the types of offers you received? Well, it was the film that actually made me fall in love with cinema and making movies. I had always considered myself beforehand a sort of exclusively theater actor. Not that I didn’t have any interest in movies — I had made Amistad beforehand, but I was far too young to understand the process. I had gone back to England with the desire to carry on working in the theater, and I did that for a while with the National Theatre and the West End. The process of working with [Dirty Pretty Things director] Stephen Frears opened my eyes up to the poetry, the very subtle, nuanced language of cinema and ways of communicating. I found it a very beautiful experience, a very peaceful and a very engaging art form – a real introduction to the art form. All of that time was a revelation to me, and then I sort of fell in love with film at that point, and I wanted to carry on making films. So when it came out, I had much more interest from America, and American directors, so then I started a process in the next few years of just working with a number of really talented, incredible people, and really learning about cinema.

In 2001, you listed LivingSpirit.com, a guerilla filmmaking destination, as your favorite website. You’ve just completed writing and directing your second short film, Columbite Tantalite. Were you always thinking about making your own films, and did you have specific stories you wanted to tell even back then?

I was always excited about making films. I was always excited about telling stories in any way, in any medium, in any capacity, engaging people with ideas and seeing if they played out. Those forms of expression have always been interesting to me. That’s why I’ve made the shorts that I’ve made, and writing the scripts that I have; they’ve always been part of me to express and create in that way.

You’re set to direct The Boy Who Harnessed the Wind. What’s its status, and what made you choose this book as your first feature? It’s in development, and it’s going well. We’re sort of getting together the last draft of it and then pulling together the financing. The story is just this extraordinarily inspirational story of William Kamkwamba, who from scrap was able to build a windmill in the middle of a famine in Malawi in an attempt to get his family out of the famine. He’s a person that I met that I was inspired by; he went on to study at an Ivy League university and is an incredibly inspirational young man and a very inspirational person.

You seem to have a strong political conscience. How, if at all, do you intend to use your position in the world to effect change, and will it include other platforms besides film? The major issue that is facing the world now is hunger. There shouldn’t be anybody hungry on the planet. That’s obviously why I was drawn to working with, and talking to, William Kamkwamba, and his story. It’s actually something we can get rid of in a relatively short period of time with the correct amount of concentration. It’s something that everybody really needs start heading to, and that’s of course what I’m going to start advocating for and pushing for; just this concentration on hunger that can actually effectively end it properly within the next decade or decade and a half. It’s a very realistic goal and something that’s completely plausible;

Besides film, what do you feel is the way to get the message out? Obviously, it’s the media. Generally, when the people are aware of it, and properly aware of it, then you really can effect change because through the media you actually get a kind of governmental attention. Once that happens, then you can actually have reform, and I believe in the democratic process in that way. You can actually gain results on a government level, and that’s the way to push through.

Do you see yourself as activist? No, not necessarily as an activist, just somebody with obviously a social conscience. We all have that responsibility.

In recent years, you’ve appeared in several historical dramas. Half of a Yellow Sun, for example, is a very personal film that captures a time you and your family endured in Nigeria. Earlier in your career, you appeared in several comedies. Are you open to doing lighter fare? Yeah, I’m more surprised comedies aren’t coming through my letterbox. I’m not really genre-specific in any way. I am drawn to drama, and that’s sort of how I started as a theater actor as well. There are people who are incredibly gifted at comedy that I just sort of watch and marvel at, and not sure how they do it, but it’s magical to me. It’s definitely something I want to explore more, and see if I can mix that with drama more. I suppose in a way, Kinky Boots was quite light, and in a way that’s the area I was interested in as well. Just the right kind of mixture of [both] comedy and drama.

Now the industry will know you’re open to comedies, although your five favorite films are fairly dark or violent — The Godfather, Miller’s Crossing, Fargo, Do the Right Thing and Raging Bull. Why do you think that is? I don’t know if I saw the five films in that way necessarily, they’re just beautiful accomplishments. To analyze them in that way, yeah, they all have sort of a drama edge to them. Yeah, maybe I am just sort of drawn to drama in that way. In drama is how I recognize what I love in live theater as well, and also sometimes what I love in performance. There was something deeply comic in a way about Raging Bull, even though nobody would ever describe it as a comedy.

It’s actually profanely funny. Yeah, exactly, and that kind of balance is so rare to achieve and just so beautiful when it comes off.

Has the list changed over time? Well, it’s always evolving and growing and changing. When anybody asks you what your five favorite films are, it depends on mood and whether it’s a wet Wednesday. Of course you put Back to the Future on a wet Wednesday because it’s one of the greatest films ever made. It’s very, very hard to choose five films, but those films sort of captured a moment in time.

What have you seen recently that just knocked you out? We’ve all been watching the same films at the moment; it’s been an incredible awards season, an incredible time in cinema. Obviously there’s kind of the spectacle that would be the extraordinary work of Alfonso Cuaron in Gravity, and the work of someone like Bruce Dern [in Nebraska], and I loved Daniel Bruhl in Rush, as well.

With all this acclaim and attention that’s being bestowed upon you now with 12 Years, what, if anything, has changed with respect to the amount or types of projects you’re receiving, how people treat you, being recognized more..? There’s definitely a level of recognition that is higher, which is nice, because it surrounds this film. Everybody involved was so deeply passionate about it and wanted to tell it in all of its depth and all of its extraordinariness. The people who have recognized me more have been very centric around 12 Years — which, from just the word on the street and the people that I meet, has had a really deep impact with people, and they want to talk about it and engage with it. Strange to say, but I haven’t felt that it’s been personal, in a way.

Like it’s all part of a piece? Yeah. In a way that sometimes the celebrity can be personal, it hasn’t felt like that. It’s felt like part of the continuing story of a film and of Solomon Northup and his extraordinary book and people wanting to engage with that really. So that’s been good. I’ve been enjoying that. People wanting to talk about the film and sort of delve into it. Obviously, professionally, these things make a huge impact, and you’re constantly striving, and in a way, earn the recognition, in a sense that you can be nominated for an Oscar. But I still feel that I do want to earn that, in a way, and continue to do work that I believe in that allows that to be possible.

Several publications that had once categorized you as “one to watch” now state you’ve “arrived,” but you’ve been acting for twenty years, so bemusement aside, where do you see yourself right now? I suppose I still feel like [I’m] at the beginning. This is an incredible period for me, and a film that I’m very deeply proud of, but actually I sort of feel it’s more of an opportunity to really dive into the next part of everything. Maybe more than the beginning. Maybe it’s the end of the beginning.

Well, you’ve said you didn’t make the decision to become an actor, and you still haven’t decided officially. [Chuckles] Yeah, yeah, that’s true. I never really made a choice to say, “Well, now I’m going to be an actor.” It was just something that I was doing. I started off doing it in school plays, high school and then that spread into on weekends. Then I went to the National Youth Theatre of Great Britain, which meant I was doing plays for the entire summer. Then, after drama school, I decided — even though it seems like a vocational decision, but wasn’t really, not entirely — I wanted to explore it more, as well as keep my options open for other things. Then I started working as an actor, and here I am. It was never a decision to cut off everything else and become an actor. It’s just something that I ended up doing a lot.

What had you entertained if the acting thing hadn’t worked out? I always wanted to work in the creative field, but I didn’t know which element of that I was more drawn to. I was always a great lover of literature.

You’re writing now, what about novels? There was a point where I thought I might go into novel writing, but it didn’t play out in that way.

Are there other vocations you might entertain? [Laughs] Well, not anymore.