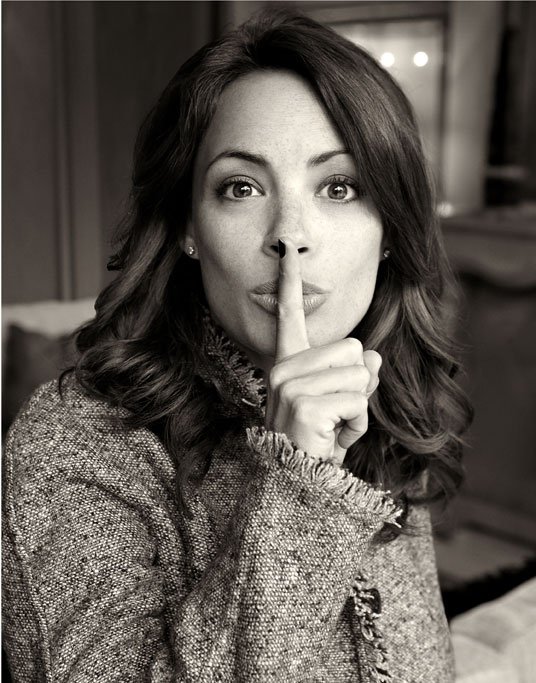

The Artist has won the Audience Award at the Austin, Chicago, Hamptons and San Sebastian film festivals. Why do you think the film is connecting with filmgoers? I don’t know. Maybe because it tells you a simple story and touches the child in you. It’s a simple story with images, only images, no bullshit. As an audience member, I went to see silent movies at the Cinémathèque in France, and I sat down and thought, “This is going to be boring, black and white, and I’m going to fall asleep and it’s going to be slow.” Actually, after a point, your imagination is working a lot trying to figure, “Is that her voice? Does she speak like that?” and you’re working with the movie, and you’re not just sitting there watching lots of things going on in front in you. You’re actually part of the movie, so I don’t know, maybe the audiences feel smarter and connect more with the movie.

The Artist has won the Audience Award at the Austin, Chicago, Hamptons and San Sebastian film festivals. Why do you think the film is connecting with filmgoers? I don’t know. Maybe because it tells you a simple story and touches the child in you. It’s a simple story with images, only images, no bullshit. As an audience member, I went to see silent movies at the Cinémathèque in France, and I sat down and thought, “This is going to be boring, black and white, and I’m going to fall asleep and it’s going to be slow.” Actually, after a point, your imagination is working a lot trying to figure, “Is that her voice? Does she speak like that?” and you’re working with the movie, and you’re not just sitting there watching lots of things going on in front in you. You’re actually part of the movie, so I don’t know, maybe the audiences feel smarter and connect more with the movie.

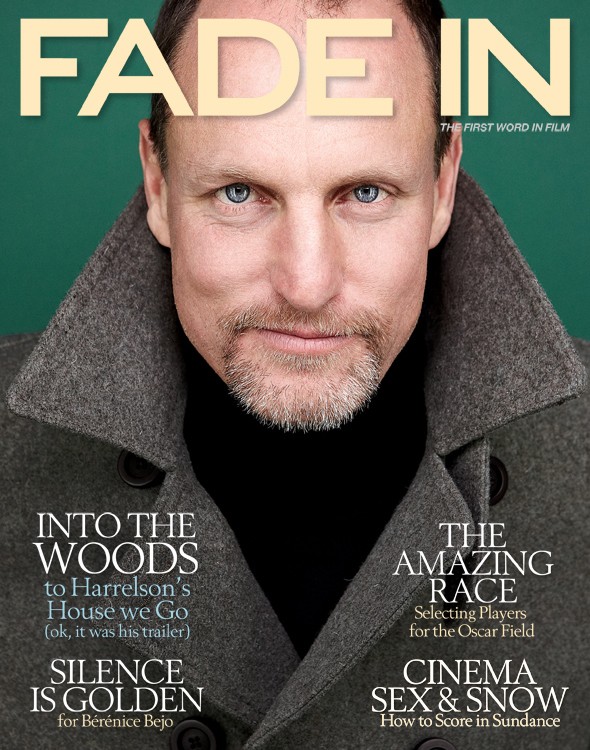

You made your U.S. debut in A Knight’s Tale in 2001, and here we are, ten years later, with your huge breakthrough, The Artist. In between, you’ve been working steadily in Europe, but was there ever the desire to come back to the States to give it another try? I did audition for films. I did almost all the auditions for James Bond girls, but from France. It’s really hard for French or European actors to break through the American movies. Marion Cotillard did it because she had a big success in France, and her movie is amazing, and she’s great, and then she won the Oscar. She’s not even a French actress, she’s an international actress. There’s no one who can make it here unless they’ve made it in their own country. Penelope Cruz is a very big star in Spain, and now she’s working here. I never thought I could make it here without a big movie.

Even for A Knight’s Tale, what happened is, [director] Brian Helgeland saw me for the lead role, but since we had Heath Ledger, who was Australian, and Paul Bettany and Mark Addy, who were from London, they were like, “We’re not going to take a French actress now. We need an American.” It’s really hard to work here, you have so many actors and actresses, and I want to do roles, I don’t want to be the “French actress” in the American movie.

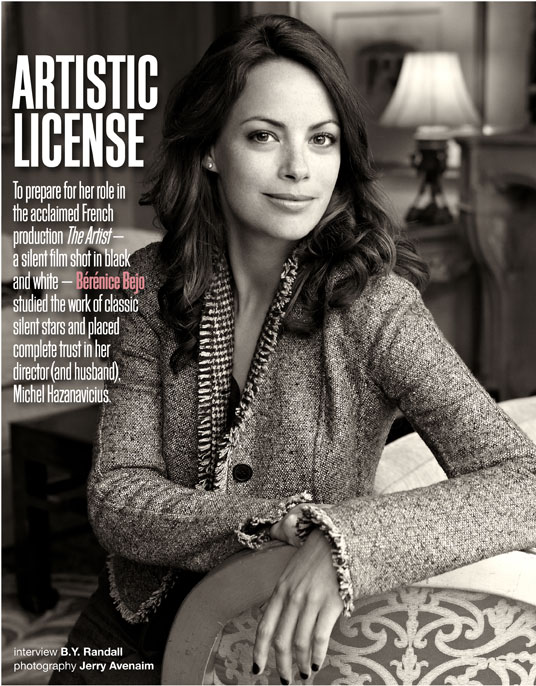

For The Artist, you studied a lot of old movie stars like Joan Crawford, Janet Gaynor and Marlene Dietrich to prepare for the role. What did you take from their performances that helped you form yours? Their body language. Like Joan Crawford with John Barrymore in Grand Hotel, there’s a great scene where they flirt together, and her eyes would go like this [she does a full body scan with her eyes], and everything was very slow. You can feel everything she wants to tell you. I just had these images when I was on set, and I remembered all that.

For The Artist, you studied a lot of old movie stars like Joan Crawford, Janet Gaynor and Marlene Dietrich to prepare for the role. What did you take from their performances that helped you form yours? Their body language. Like Joan Crawford with John Barrymore in Grand Hotel, there’s a great scene where they flirt together, and her eyes would go like this [she does a full body scan with her eyes], and everything was very slow. You can feel everything she wants to tell you. I just had these images when I was on set, and I remembered all that.

When you’re acting in a silent film, how do you calibrate your performance? That’s [writer-director] Michel [Hazanavicius]. He would tell me, “This is too much,” or “You can go more.” Like the interview scene: He told me I go down from the stairs, and I sit down for the interview. He would keep telling me, “Move your hips more and more, go for it.” I was like, “Really? This isn’t too much?” and he would say, “Just go for it. Overact.” When you watch the movie, you’ll see that I really go for it, and what it says is that she’s very comfortable, and she’s thinking she’s great. That’s Michel’s direction to help me to feel the character as to where she’s at this point. Then, when I sat

down, he was telling me to blink my eyes and do more and more. My voice was so horrible on this scene because it was so high, but my body was true, so I could just go for it. Every time I finished the scene I would apologize to the crew because I thought it was so over the top. And then I go and see the dailies, and it was great. You really have to trust the director for this kind of movie.

down, he was telling me to blink my eyes and do more and more. My voice was so horrible on this scene because it was so high, but my body was true, so I could just go for it. Every time I finished the scene I would apologize to the crew because I thought it was so over the top. And then I go and see the dailies, and it was great. You really have to trust the director for this kind of movie.

So you spoke dialogue on the set while filming. Was it scripted? Yes, except for the scene where the two meet on the stairs. That was improvised.

And Michel played music on the set. What kind? He would choose, and then wouldn’t tell us. My first scene that I shot was when I come from the hospital, and I see him lying on the bed, and I cry. That was my first day of shooting…thank you. [Laughs] Michel put on a song that I love from Laura, [directed] by Otto Preminger, so obviously I was surprised, very moved. So you’re acting a scene, but at the same time, you’re thinking about something else. I was very moved because the director, who’s my husband, chooses a very nice song, so he knew. He was playing with us. He used the music to help us be in the right emotion.

The last part of the film uses Bernard Herrmann’s score from Vertigo. What prompted that? When Michel did the editing he put music in, and talked to the composer, and told him, “That’s the mood I want for the scenes.” The composer didn’t have a lot of time to compose the music because we wanted to go to Cannes, and he did a very, very big job. It’s an hour and a half of music. Michel couldn’t stop thinking of the Herrmann music, so he said, “It worked so well for the movie, I can’t take this out of my mind with the images.” So he decided to keep it. It’s a choice. Some people hate that because it takes them away from the movie and takes them to Vertigo.

The film is really about unspoken love. How much do you think it would’ve changed the dynamic if they had gotten involved? Was there ever a discussion about it? At one point, where they meet in his dressing room, they were kissing, and Michel realized at that point the character becomes unfaithful, and people won’t like him. So he took that away, and actually it works. Do you think they’re not together at the end of the movie?

You get the idea, but it’s just more about what’s not spoken. Yes, and for Michel, at the end of the movie, when they’re dancing, it’s like they’re making love. It’s the purity of the love story and being back in the time. People actually like that. It’s true that some people say, “Oh, but they don’t kiss at the end!” but maybe it’s more romantic. Again, you fantasize. You don’t hear their voice, you don’t see them kissing. We’re so used to seeing actors kissing and making love like we don’t know what it is.

Is it true that Peppy didn’t have as big a part in original drafts? It’s funny, because at the beginning, Michel wanted to write a story about a man, and he said to me, “There’s going to be a role for you, but it’s going to be a small part, and I want you to do it.” I was like, “Of course, whatever you want.” Then he started writing the script, and as a writer, sometimes a character just becomes stronger and stronger, so the story became about him and her. Actually, I remember saying to him, “The dog has a bigger character than me, and has more lines.” He made fun of me and said, “But you don’t realize how your character is always in action.” I didn’t understand what he was saying, but then I started working on the character with my coach, and then, when Michel started editing the movie, that’s when Peppy became stronger. It’s because he cut a lot of things of [the character] George Valentin being a movie star, on set, things like that. He cut all that, and suddenly my character became bigger, because there was less of George, and they were even. Advantages and disadvantages of working with your husband as director? Just advantages. No disadvantages. As an actor, you arrive on the script two months before shooting. You don’t know anything about how it is to find the money and to fight. So it was great seeing Michel having ideas. Like the dog — a friend of ours lives here, and one day we were talking on the phone, and we were talking about our dogs. I asked what does his dog do, and he said “When I go ‘Bang!’ he falls and dies.” And I said that to Michel, and he thought it was a good story, and said he’d keep that for a movie. So I was part of that, and the part where I come in and put the jacket on, and feel the jacket. So I was part of the process of the writing. I love being part of the creative process. And then he was really knocking at everybody’s door, producer, distributor, to find the money, coming back home and saying to me that it’s a universal movie because there’s no language, [so] we can sell it all around the world. It’s so amazing for an actor to see all that happening. I met him as a director first, and then we were together after the first movie we did together, so I respected him as a director before even loving him as a man. And I was really impressed with him, so I couldn’t wait to work with him again. And he’s very smooth, very nice with everybody. Very easy to work with him.

Advantages and disadvantages of working with your husband as director? Just advantages. No disadvantages. As an actor, you arrive on the script two months before shooting. You don’t know anything about how it is to find the money and to fight. So it was great seeing Michel having ideas. Like the dog — a friend of ours lives here, and one day we were talking on the phone, and we were talking about our dogs. I asked what does his dog do, and he said “When I go ‘Bang!’ he falls and dies.” And I said that to Michel, and he thought it was a good story, and said he’d keep that for a movie. So I was part of that, and the part where I come in and put the jacket on, and feel the jacket. So I was part of the process of the writing. I love being part of the creative process. And then he was really knocking at everybody’s door, producer, distributor, to find the money, coming back home and saying to me that it’s a universal movie because there’s no language, [so] we can sell it all around the world. It’s so amazing for an actor to see all that happening. I met him as a director first, and then we were together after the first movie we did together, so I respected him as a director before even loving him as a man. And I was really impressed with him, so I couldn’t wait to work with him again. And he’s very smooth, very nice with everybody. Very easy to work with him.

How hard was it finding the money for The Artist? Very hard. Impossible. No one wanted to put money in it. TV said, “We don’t want to read the script, because we know the script is going to be good, but we won’t be able to put money in it, because we can’t sell it. We can’t put it on TV, nobody’s going to watch it because it’s black and white and silent.” That was terrible.

Why do you think it was difficult to find money? Because in France, television gives money to the cinema. If you cannot put your movie at eight p.m. for all the family, then you don’t want to put money into a film, because you can’t then put it on TV. They said people just change channels, and if they change to a channel that’s got a black and white film, and it’s silent, they’ll go “Oh, no.” Nobody is going to stop and watch. But that’s not true, because in France, the movie is already doing really well.

Is that when [sales agent] Wild Bunch stepped up? Thomas [Langmann] came first, the producer, who’s one of the two biggest producers in France. He put money, like literally from his own pocket, which you never do. You don’t have that anymore. Never, never. You know what the difference was? He accepted that he was going to lose money with this movie. And that’s when Michel said, “Okay, he doesn’t care about earning money. He just believes in the project, and wants me to do it, and is allowing himself to lose money.” And that’s how it started, then Wild Bunch came on, and then Warner Bros. France saw some dailies and came on. I remember the head of Warner Bros. France called Warner Bros. here and said, “I’ve seen dailies of this movie, and it’s black and white and silent, and it’s great, and I want to put money in it.” And Warners here said, “Okay, but it’s your own responsibility.”

So you have a film about Hollywood that’s a French production, yet filmed entirely in Los Angeles. When you were making the film, what was the industry reaction from the locals? It was amazing. People would hear about the project and call to work on the project. We were little French people, and it was “OK!” And for the actors, John Goodman read the script, and in five minutes said he wanted to be in the movie. James Cromwell read the script, and he did an audition with Michel asking him so many questions. The audition went in reverse. James wanted to know everything about the movie, and why this and why that, and after two hours he said, “Okay, I’ll be your lady,” which was very touching for Michel. But the people from the crew were so happy and proud to be part of this movie. I guess because you’re never going to do this movie. And actually, the makeup artist who was working on the promotion, too, he used to say, “This is going to be in the running for the Oscar.” And we’re like, “Yeah, well…” Michel, Jean, me and the DP were always like, “I hope we’ll be able to go back to L.A. and show the movie to the crew.” We were obsessed with that. But we didn’t know, because it’s so much money to come and do a screening, we were like, “I hope we’ll be able to show you the movie, or maybe we’ll send you DVDs.”