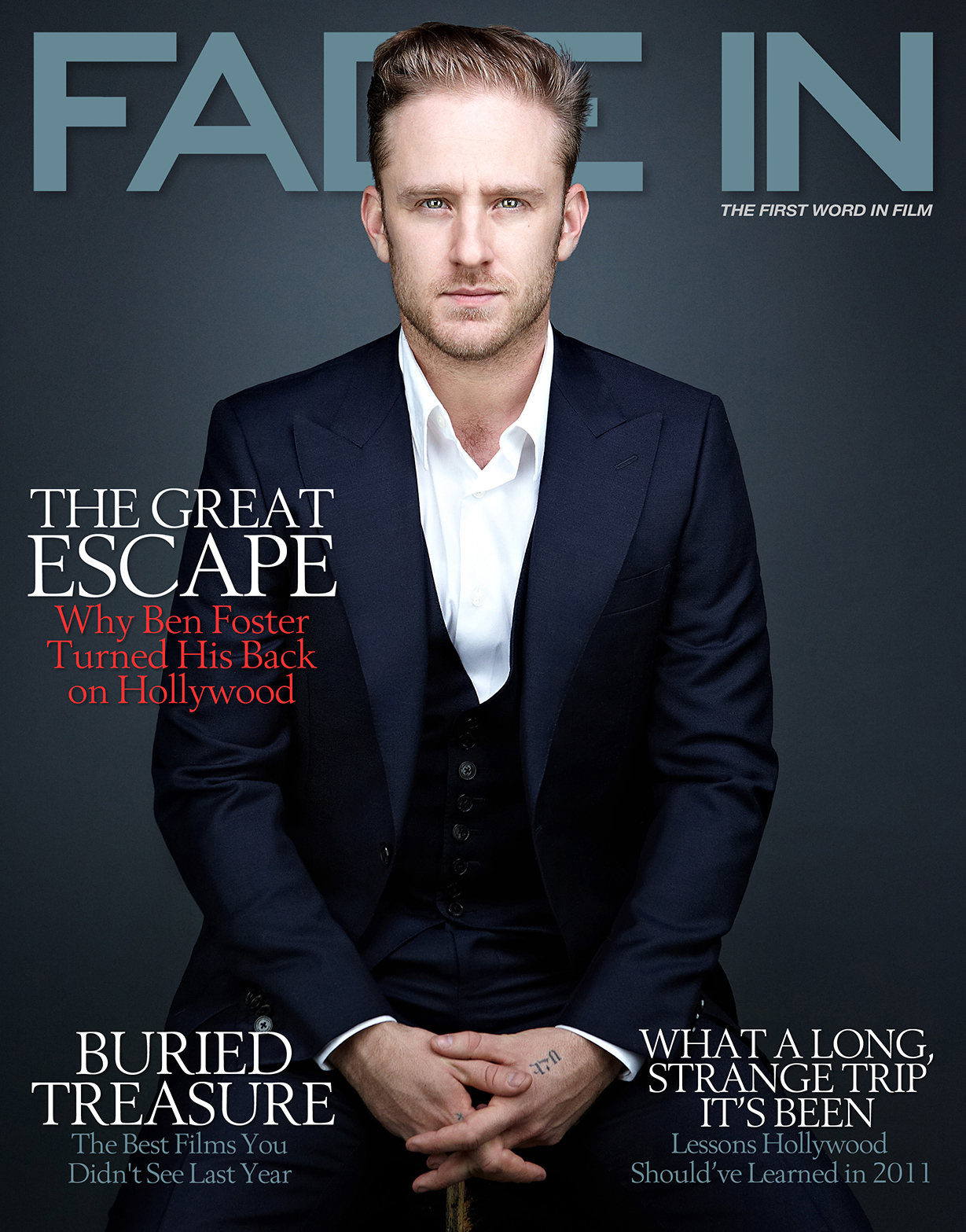

Not many people from farm country – or anywhere else, of that matter – are practicing Transcendental Meditation by the time they’re in kindergarten, but Ben Foster, pride of Fairfield, Iowa, was at it at age four. His precocity didn’t end there: at twelve, as a member of a Fairfield-based arts program, he co-wrote and starred in a play that earned international recognition. And by sixteen, he had left the Hawkeye State for L.A., where he was soon cast in the Disney Channel series Flash Forward. A few years later, in 1999, he broke into features with a supporting role in the acclaimed drama Liberty Heights, written and directed by Oscar winner Barry Levinson. Since then, Foster has remained on an up escalator, working steadily and building a solid resume of projects with several other respected helmers. In movies like Alpha Dog, directed by Nick Cassavetes, 3:10 to Yuma, directed by James Mangold and The Messenger, directed by Oren Moverman, he delivered performances with the sensitivity and intensity of a young Sean Penn.

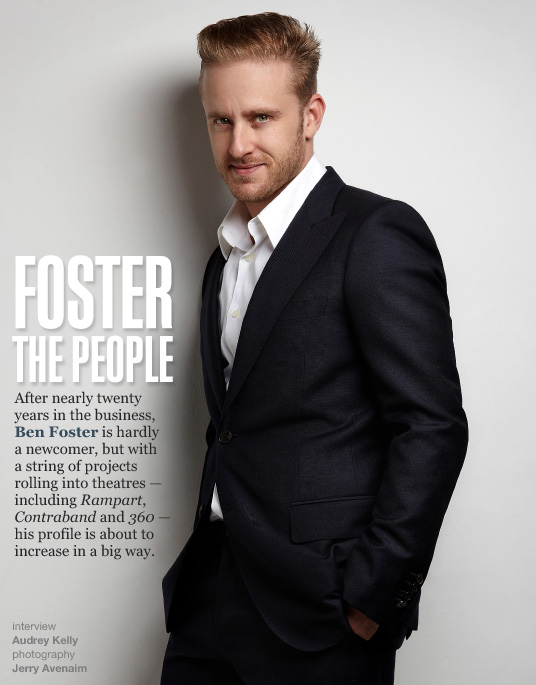

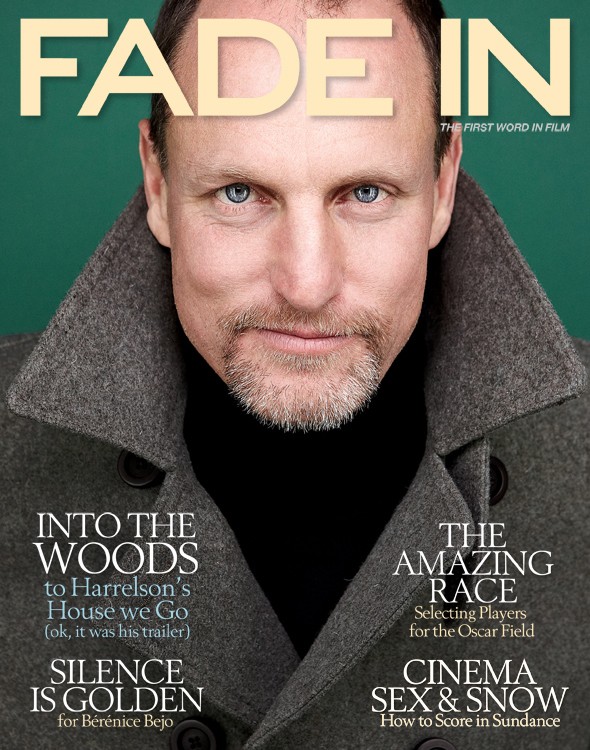

Soon to come is a string of other noteworthy films, beginning with the crime thriller Contraband, starring Mark Wahlberg, followed by Rampart, a cop drama that reunites him with Moverman and his Messenger co-star Woody Harrelson. Later in the year brings 360, directed by Oscar nominee Fernando Meirelles, with a cast that includes Oscar-winners Anthony Hopkins and Rachel Weisz and Jude Law.

To cap this high-profile run, Foster is scheduled to start work soon on what may be his headiest project to date: Gotti: In the Shadow of My Father, a fact-based drama about the relationship between John Gotti, the flamboyant Gambino crime family boss known as “the Dapper Don,” and his namesake son. The film, directed by Barry Levinson, stars John Travolta as Gotti and Al Pacino as underboss Anielleo Dellcroce, with Foster in the pivotal role of Gotti, Jr.

Although he is perhaps best known for playing troubled, often unhinged, characters – ranging from Lauren Ambrose’s art-school boyfriend in the HBO series Six Feet Under and Angel, the winged mutant in X-Men: The Final Stand, to loose-cannon crooks in Alpha Dog, Yuma and The Mechanic – Foster in person is low-key and thoughtful, a guy who prefers the solitude of an Airstream trailer in northern California to late-night clubbing. But he is not without passion when it comes to discussing his work, both as an actor and as a producer, and in singing the praises of his younger brother, Jon, whose own career is starting to take off.

After nearly two decades in Hollywood, Foster has seen his share of cautionary tales. But unlike some of his peers, who have succumbed to the pressures and temptations of the business – which, as he puts it, “certainly puts you on a collision course with yourself” – he has not just endured, but thrived.

Reflecting on why he made it and others did not, he sounds very much like the grounded heartland product that he is. In Hollywood, “you get to find out what you’re made of, and who you are, pretty damn fast,” he says. “What are your values? What do you value? If you can hold onto to those, then maybe you’ll stick around for a minute.”

Or, in Foster’s case, a lot longer than that.

You lived in Los Angeles for years, but don’t you now split your time between Northern California and New York? I have an [Airstream] trailer in Northern California, and I go there for refueling. But I live now in New York, and have for three years.

Well, you’ve been on a tear lately. You’ll have both Rampart and Contraband in theatres this month, and you have a lot of films in the pipeline. Yeah, and again, nothing’s done until it’s out, you know? But I’ve been enjoying some solitude in the big trees in my trailer. That’s a good anchor.

Very Into the Wild of you… Except it has a different ending.

Of course, wasn’t talking about the ending, just getting out of the fray. The racket. Sitting in the trailer with the propane tank, making your scrambled eggs, making your coffee, looking at the mountain lions. It’s been great. I’m leaving tomorrow [for a press junket in New York]. Gotta shave the beard [laughs] and go sell some movie.

Didn’t you also take a year off after The Mechanic? After The Mechanic, I shot 360, which was a great experience. It was nine months to get Rampart off the ground, shot and then went to New Orleans for three weeks [to shoot Contraband], then hopped back in the editing room [on Rampart], and then went to London for three weeks, shot [360], and then came back for the final cut of Rampart. Then we’ve been on the press train getting it out there. So I’m thinking in terms of being in front of the camera, [it’s been since] spring.

“Hollywood will find every weak point in your heart and in your mind, and try to blow it out. And that may be by making your candle so bright that it just fizzles after a few years, and I saw a lot of good kids go down by their own hand, being run over by rejection, being swallowed by success. I’ve been very fortunate.”

“After doing Six Feet Under, I was only getting bisexual art student projects. Then when I did 310 to Yuma, there was a swell of westerns. Alpha Dog was nothing but drug addicts. People are fairly narrow-minded in terms of playing people whose values or faculties are a little imbalanced. I’ve never looked for those roles, but it gets down to the people that I’m playing. Do I ask some questions or learn something [from] these people or this material?”

Why was it important for you to make Rampart? It was the opportunity to play with the gang again. I moved to New York to start this production company with Oren [Moverman]. We’ve been gathering material. And this was the first script that got the green light for our company to produce. So the fact that there’s no one else in the world that could play Dave other than Woody, it was very natural.

How did the production company come about? Well, Oren and I met for The Messenger, and it was an immediate shorthand. The process was unlike any that I had experienced previously. After we got back from doing some festival, I was supposed to head back to L.A., and I just got online, put a pause on my ticket and called up Oren and said, “You know, I think we should keep on making things.” He said, “Great, let’s figure out how to do that.” So we started collecting material, from that point on. We got a book by [William S. Burroughs and] Brion Gysin titled The Third Mind, about two minds coming together creating a third entity. We’re both big Burroughs fans. In fact, one of the projects we’re producing is the film Queer, based on his book, that Steve Buscemi’s going to direct hopefully next year.

What’s the name of the company? The Third Mind Pictures.

It seems like more artists are trying to own pieces of their films. What is the benefit, and was that of some interest to you in starting the company? It’s kind of like doing interviews. The drag of it is that it’s being documented in permanence, and you may be misquoted. The other side of that is that you may be quoted accurately, and you have to live with that. The ownership of material in saying, “All right, well, we control this,” means we are controlling the questions that we’re asking. That’s the drug we’re chasing.

Producing is time-consuming. How will this affect your acting career? I prefer it if we can prep a film for a year and shoot it for a year, but you’ve got to pay rent. I like the long haul. There’s different kind of producers as well, right? There are number pushers, the guys who deal with the permits, there are those who grease hands and then there are those who are interested in the creative side and in protecting the director’s vision. I suppose that’s where Oren and I are most comfortable. You find your strengths and your weaknesses very quickly. Oren and I collaborate in a similar fashion. There’s an aggressive interest in research and a pursuit of creating environments that support accidental gems.

Are you referring to the improvisation that Oren allows on set? It was about proving a point and asking questions, so if you do your research, and you do your homework, and you come in and create an environment that allows the actors to listen to each other, you can do no wrong. It’s all about protecting that space.

What was the hardest part about producing the film? The hardest part is also the greatest thrill, which is you’re confronted with 200 different problems every day. And they need to be solved, and answers need to be produced. That challenge of puzzle-solving exercises a part of my brain that, in film, [being] in front of the camera, doesn’t. I find that incredibly rewarding.

It was also probably hard to have your star, Woody, not like the first cut of the film. That was difficult, certainly. But it’s like family; you may not be talking for a while but the bond is so strong that you can come together and meet eye to eye. You don’t necessarily have to agree, and this is one of the happy endings that you’re lucky enough to have is there were some extreme changes in a very old cut of the film that’s different than what’s on the page and what we shot. And that’s where Oren is a master in sculpting and tone. When Woody saw it again, a second viewing, we sat next to each other, and he just looked at me afterwards and said, “I don’t know what I saw before, but I love this movie. I was wrong.” That was hugely rewarding.

We just visited Woody on the set of Seven Psychopaths. [Laughs] Aptly titled.

Did he tell you about his George Harrison dream? No. That’s odd, because George has come up three times today in conversation…now four.

You’re joking? Were you talking about the HBO special, or…? No, there was a song that came on the radio, which then led to a conversation with Rampart producer Ken Kao. We were both talking when George came on, and Ken asked if I’d seen the HBO series, and I said I hadn’t. Then we got into a conversation about TM [Transcendental Meditation], which I’ve been practicing since I was very young, and then another one of George’s songs came on again, and now you’re telling me about Woody. So George is in the air today.

That’s wild. Well, you’ve worked with Woody a couple times now. What’s one of your best stories about him? That’s really tough. He’s my brother. I can’t really think of a particular anecdote other than every day being in awe of his performance and commitment. Woody’s a national treasure.

You’re right about that. He’s very spiritual. Do you consider yourself to be? Well, I wouldn’t go on and compare us in a pissing contest of connectivity to the universe, but I would say we use different doors. There’s a shorthand there, I suppose.

What attracted you to Contraband? I love New Orleans, which is where we were shooting. I wanted to work with Mark [Wahlberg], which was a gas. I was interested in playing with the role, but on paper it was fairly two-dimensional. The game of humanizing 2D is a challenge.

You’ve been acting since you were sixteen? Fourteen.

Have you ever thought what you would have done if acting didn’t pan out? Photojournalist. You travel, you get up close.

Do you remember what you were first expecting when you first arrived here in L.A., just starting out? Oh, boy, that was eighteen years ago.

What do you remember about those days? It must have been tough along the way, sometimes not working for periods. Oh, sure, yeah. Hollywood is a very conflicted place. As a young person, attempting to find your own voice can be…Nick Cassavetes said something really lovely to me that I’ve held onto about some silly job that will go unnamed that I didn’t want to do. It seemed like a move rather than a question worth asking. He said, “Well, [do it], [do it] if you have to, but just make sure you don’t blow your own candle out.” And Hollywood will do everything, it will find every weak point in your heart and in your mind, and try to blow it out. And that may be by making your candle so bright that it just fizzles after a few years, and I saw a lot of good kids go down by their own hand, taking their own life, being run over by rejection, being swallowed by success. I’ve been very fortunate. I would have been near a lot of it, but I’ve been working pretty steady, and that’s a blessing.

But it can get to you. Certainly. I had three friends take their own life in one year. Hollywood is no joke on a little kid’s heart. You know, there’s some little light in them. When they come to this town, maybe they feel they have something special, they feel they have something to communicate, or they don’t know how to be in the big, bad world as a flesh person between the metal and the concrete, they just need to make believe. It’s a distilling place. I’m not going to say it’s good or bad. I can’t judge that. But it certainly puts you on a collision course with yourself. On the upside to that, you get to find out what you’re made of, and who you are, pretty damn fast. What are your values? What do you value? If you can hold on to those, then maybe you’ll stick around for a minute.

Did your background in meditation help you? For sure, yeah. How to find your own voice; how to find stillness amidst chaos. I’m never one to push one belief or one system over another. Basketball can be meditative. Taking a walk in the evening can be meditative. The rigor and the discipline in honoring a time that is just for either reflection or turning off your phone can be very useful to maintaining some shred of sanity. And TM works for me.

Were you concerned when your brother wanted to get into the business? No. He’s a movie star. He just hasn’t hit yet. He’s at a tricky age anyway, and people are going to be quite surprised. He’s the most incredible man I know.

And he has you to give him advice… Well, I don t know if I can give him advice. He’s pretty sharp. He’s not one to get caught up, you know?

You’re acting, producing — is directing the next step in your evolution? You’ve been tinkering with cameras all your life. If there ever is a right time, then it will arrive. Right now it’s about working with pals and keeping it close. You know, when you’ve been doing this long enough, you realize it’s not worth your time to do it with people you don’t believe in, don’t care about.

Right. Well, it does take a lot of time out of your life, making a movie, promoting it. It does. It’s the greatest job in the whole wide world. It’s an absolute luxury problem to be dealing with the issues of making a film worth seeing.

What’s the worst thing about being an actor… besides interviews? Besides talking with you, which is very easy, I have to go do a press junket in New York. It’s like speed dating.

I would say working with people who are not of like mind, who are aiming for a product, or even an element of perfection…the package of it all. It’s fatiguing. The greatest part of being an actor is the research. Learning about some things as intimately as possible in a short amount of time. I suppose I liken it to immersion journalism. You meet with people, talk to specialists and interview them, and come in naive. That’s the greatest part. All the technical aspects one has to ignore, and then you throw it all away and listen to each other, and there’s these brief windows of communication that are addictive.

We get edited as well. You have an editor who edits your research, and sometimes you have a great editor, and sometimes not. Some of the great nuances can be lost, and one has to live with that. Al Pacino said something beautiful, which I’ve stolen, which is, “I bring the lumber, you build the house.” And so I suppose I want to build the house.

“The hardest part [about producing] is also the greatest thrill, which you’re confronted with 200 different problems every day. And they need to be solved, and answers need to be produced. That challenge of puzzle-solving exercises a part of my brain that, in film, [being] in front of the camera, doesn’t. I find that incredibly rewarding.”

“Working with people who are not of like mind, who are aiming for a product, or even an element of perfection…the package of it all…[is the worst part of being an actor]. It’s fatiguing. The greatest part of being an actor is the research. Learning about some things as intimately as possible in a short amount of time.”

A lot of your films have crime as a backdrop or subject matter. What is it about the darker side of life that appeals to you? Conflict. Life is conflict. We’re in conflict with ourselves, with our loved ones, with our bosses, with our family. All the time, we let our loved ones down. In the end, we’re all people, and you can’t judge that in work or in life. Drama is conflict.

There was a point in your career where it seemed like you were playing one sociopath after another, and doing so incredibly well. Did you find that period frustrating at all? Were you only being offered psychotic roles during that time? If so, what did you or your agents do to shake that trend — or have you? Well, after doing Six Feet Under, I was only getting bisexual art student projects, and then when I did [3:10 to] Yuma, there was a swell of westerns, and Alpha Dog was nothing but drug addicts. People are fairly narrow-minded in terms of playing people whose values or faculties are a little imbalanced. I’m not looking for, and I’ve never looked for, these roles, but it gets down to the people that I’m playing. Do I ask some questions or learn something [from] these people or this material? I don’t know how to answer that…I don’t feel stuck or broken or psychotic today, so…

Ever come across a situation where someone recognized you but thought you were your character? Yeah, but it’s all friendly. It’s great. If anybody likes what you do, how great is that? It’s rare you go up to a waitress and say, “You know what? You did a terrific job today. I really liked how you dropped off that coffee.” And she may have done that with the most elegant humility and focus, but she’s not going to get that, so if anybody likes what you do, or thinks you are who you played, it’s great.

There’s some eccentric people out there but catch any of us on the wrong day.

What’s it going to take to get you to mix some comedies in there? I’m looking.

Hasn’t Judd Apatow come knocking? I’ve knocked on Judd’s door, and nah, it hasn’t happened yet. I don’t know. I would love to. I thought that was going to be the route, but not yet. I’m looking constantly. If you find one or write one, let me know — a smart comedy, or one that’s interesting, is very hard to come by. When you watch one like Harvey or The Jerk, these masterpieces, they just don’t come around very often.

It was reported that you wrote a play when you were quite young. Are you still writing? Yeah, yeah. I was part of a program called Odyssey of the Mind, which is an international program where you spend all year with your classmates writing. So we wrote and directed two plays in school in Fairfield, Iowa, and we got some international recognition. That was a real bug that I caught: the collaborative process. I’m still trying to do it.

Still trying? Are you saying that because you’ve yet to put it out there? Uh, haven’t put it out there yet. There are a few things that are aiming towards [that].

You’re about ready to switch gears and immerse yourself in mob culture with Gotti. Yeah, that’s what it’s looking like. Waiting for the final go ahead. It was on rocky ground for a minute there. I gained thirty pounds, lost thirty pounds. But it’s looking like there’s some work to be done in the new year. And I’m really excited to be reunited with Barry [Levinson].

So you have to gain back the thirty pounds? [My character] has a different body type than me, and he ages from twenty-five to forty. There’s a lot of prep time, which is good. It really punishes the ol’ sciatica, you know?

What made you say yes to that film? Getting to work with Barry again. It’s a beautiful script, unlike any mob film I’ve ever seen. It’s relationship-based, and how can you turn down that cast? Travolta? Al Pacino? Barry gave me my first break, so it’s been awhile. And then I get to eat a lot, so…what? Wine? Pasta? Of course! No, I’m prepping. I’m prepping, darling. Let me take a nap here at the table.

Do you get intimidated any more when you’re working opposite these megastars that you grew up watching, like a Travolta or Pacino? I don’t know if intimidated is the right word. Excited. These guys have a catalogue of stunning work behind them that they bring to the table. I imagine what it would be like to be a musician and get to play with people that you’ve listened to for so many years, and who have inspired you, turned you on. It’s an honor.

So you don’t get nervous? You just bring your A game? Yeah, bring your A game, but they will raise your game. And then, on top of that, these are professional make-believers. These are people who refuse to grow up. These are full-grown adults in costumes.

Is that what our problem is? [Laughs] So what are you gonna do? Are you gonna put a real bullet in the gun? Are you going to say something mean to me? Really? We’re there to work, and I’m very lucky to work with some heavies.

What happened with Prometheus? It was reported you had joined the cast. IMDB says a lot of things.

Well, let’s clear it up. I was never cast.

Don’t believe what you read, kids. That’s right.

Have you seen 360? I have. I like it a lot. It’s a beautiful film.

How’s working with Fernando Meirelles different than working with other directors? Fernando is so elegant in his approach. He loves actors, loves to try things, very relaxed. He’s not on an ego trip. He loves to make things. I’d work with Fernando in a heartbeat.

What else is close to your heart these days? [It’s] something family-oriented, and it’s called ConquerCancer.org. My auntie Susan started this program through the loss of her husband, my uncle. And she’s been raising money single-handedly — also with my Nana, who passed a year and a half ago of the same disease. It’s just tremendous what they’re doing, and it’s growing. It’s homegrown and grassroots, and I’m really proud of her, so any chance to get it out there.

According to the Mayan calendar, the world’s ending in December. If you knew this to be true, how would you spend this year? I guess making movies takes too long, right? I don’t know, maybe get into Internet porn. That hits the market pretty fast.

What?! [Laughs] Not a long turnaround. You can bang them out real fast.

You’d have to move back to L.A. for that, Ben. Yeah, but there are some festishes that I could specialize in and do on my own. [Laughs] I’d say, probably go back to the trailer.

Really? Yup.

What is it about that trailer? Uh, no one’s around.

So you don’t like people? I love people. I think those that hate people have just been so wounded by people that they were hoping to be received by, or to connect with, and they’re the ones with the big hearts. I used to say that I hated people, but I think it’s a cop out. I don’t mean to be aggressive about that, it’s just, again, you can’t judge a character, you can’t judge a person, if you really want to get to know them. We don’t know where anybody is coming from. We just make these blanket generalizations about who they are and what they are, but we just don’t know.

That’s fair, but that doesn’t necessarily explain why you like to sequester yourself in a trailer out in the wilderness. Well, there’s a lot of racket. I can be on my BlackBerry in Starbucks, I guess. [Laughs] I could be hunting some Mayan temple and really getting at the eye of it, but big trees make me happy.