When The Shining first opened thirty-two years ago, director Stanley Kubrick’s interpretation of Stephen King’s enormously popular novel was met with decidedly mixed reviews and mild success at the box office. Defenders said the film was a terrifying adaptation, while detractors thought Kubrick was firmly out of his element.

Time, however, has a different means of being the final judge.

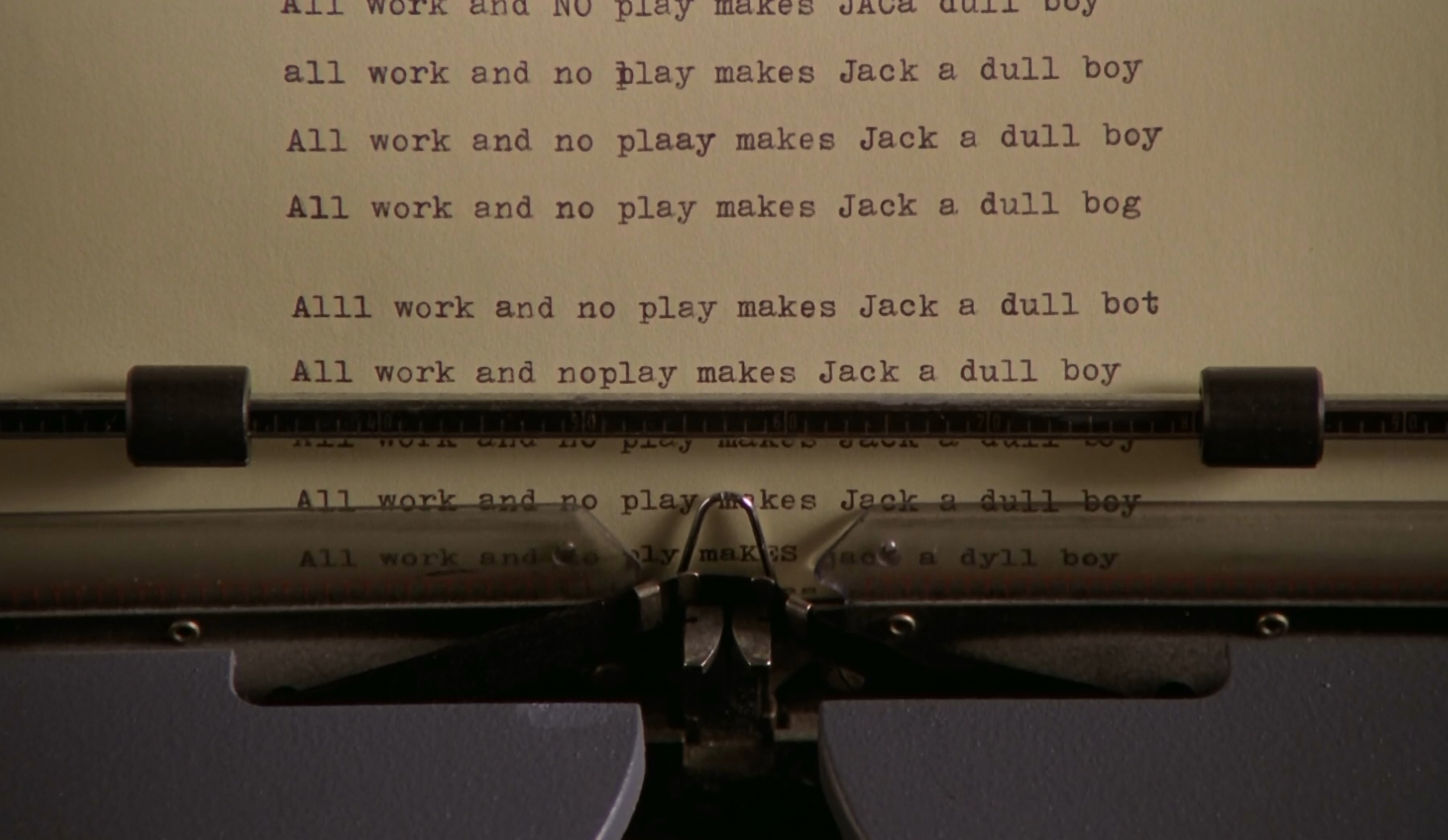

Over the past three decades the film has grown in cult status, and along the way, something truly fascinating has arisen around the evil doings at the wintry Overlook Hotel. Several theories regarding secret messages, themes and metaphors hidden in the film have sprung up, spawning a veritable cottage industry.

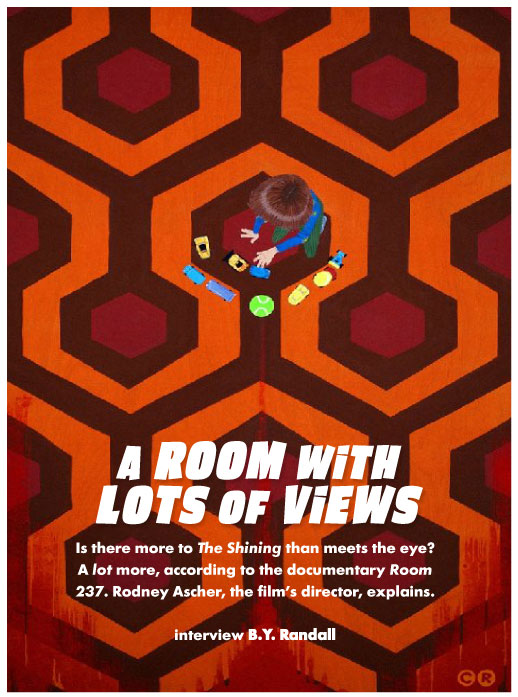

The upcoming documentary Room 237 gives light to nine such theories, contending that the film represents everything from a treatise on the American Indian genocide, to the Holocaust, to a faked Apollo 11 moon landing. They’re put forth by a news correspondent, a performance artist, a history professor, a playwright and a filmmaker who share nothing in common other than an obsession with Kubrick’s grand guignol neo-classic.

The director, Rodney Ascher, is a Los Angeles-based filmmaker whose background is in the world of shorts, commercials and music videos. He got his start as a storyboard artist on the 1993 film Wide Sargasso Sea, and over his twenty-year career, he has worked in virtually all aspects of production — ideal preparation for Room 237. Avoiding a traditional documentary approach, Ascher presents a mash-up of scenes from other movies, Kubrickian and otherwise, while the theorists opine over the soundtrack. The end result, described as a “subjective documentary,” employs a most unconventional method, but is one well suited for the esoteric, occasionally paranoid, subject matter.

The seeds of Room 237 were sown with Ascher’s 2010 documentary The S From Hell, an amusing eight-minute short in which several men and women recall the Screen Gems logo of the 1960s, and how it terrified them as children, which also became an official selection at Sundance.

Ascher’s innovative approach to the documentary form has earned critical plaudits for 237, and invites viewers who are so inclined to seek deeper meaning in the film’s interpretative layers. Fade In recently sat down with Ascher to discuss the genesis and reach of the film, and in yet another seemingly impossible coincidence, the interview was conducted at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art on the very same day the exhibition of the life and work of Stanley Kubrick began its eight-month run. The choice of meeting location was completely random, chosen by the magazine based solely on the filmmaker’s location… or was it?

When did you first start to become aware of all the theories about The Shining? I’m not sure, exactly; probably early in 2010. A friend of mine, Tim Kirk, who is the producer of the film, emailed me one of the new ones that had started to circulate, and it immediately blew my mind. I had always been a fan, and I remembered there was a book I had, Thomas Allen Nelson’s Kubrick: Inside a Film Artist’s Maze, and there’s like a half-page fine-print footnote about the numerology of 237, so I was ready to believe that people were looking at this movie in this extreme kind of detail. So then the two of us just sort of made it our mission to see how much other stuff was out there.

I had done a short documentary about people who were obsessed, and had childhood phobias about the logo for Screen Gems, and it seemed like people obsessed with The Shining might be an interesting follow-up. As the two of us looked, we were kind of amazed and delighted to find that in the last couple of years, countless people have just been poring over The Shining like the Rosetta Stone or something, trying to decode all the signs and symbols, messages and meanings inside. That was early 2010, because Tim and I did eight or ten months of research before I conducted the first interview, which was in January of 2011, because I remember it was almost exactly a year before our premiere at Sundance. So it was only eight or ten months before then where we really started to look around and see how many people were doing this kind of work.

Before you settled on the final nine theories, how many were being entertained? I don’t know that we counted them, but there’s certainly an awful lot more than was included in the film. When we started the interview process it wasn’t like we had settled into what are all the ones that are going to be included. We started with Bill Blakemore because of his article about the American Indians in 1987 [Blakemore contends that The Shining is about the American Indian genocide and its consequences]. He kind of got the ball rolling, and a lot of people referred to it. After our first phone call, that was some four hours long, ended I was kind of vibrating, saying, “This is a bigger, more interesting story than I had thought.” Because he’s not just pointing to stray images in the film and saying what they mean, he’s bringing his whole history to this film. His life as a journalist, and what he’s experienced first hand, and using that to help him understand the film, and that’s even more interesting than somebody who’s just looking at the movie as a puzzle.

And so from there, I forget who was our second interview — it might have been Jay Weidner [who believes that The Shining is Kubrick’s veiled admission that he helped NASA fake the Apollo 11 moon landing] — it was like, “Let’s do someone very, very different, who’s coming at this from a very different perspective.” Sort of map out some of the poles, and then we’ll start filling in. So if we’ve got five people, and the movie is in nine chapters, there’s at least as many that aren’t in that are in, and of the interviews that we did, we’re using ten percent of the interview time that makes it into the final film. There’s two guys in particular who have written an awful lot about The Shining who didn’t wind up being in the film. One is Kevin McDonald, who writes under the name of “Mastermind,” and has this amazing site, which is incredibly deep and intimidating because it’s pretty small type and it goes on for a while. And in Liverpool, Rob Ager has been writing about Kubrick and The Shining for a while and has made some amazing little YouTube videos where he analyzes the blood coming out of the elevators, and has found the figure of a person who is sort of submerged in the blood, and it goes on and on and on.

What did you not include that you just thought was way too out there? It wasn’t that the stuff was too out there; there were things that I didn’t understand. Maybe there was a push where, for me to see an image, I needed to turn an image sideways, or it was also just not that different enough from what we already had, and then there were people we couldn’t find. There’s a guy whose site, “jonnys53,” hadn’t been updated in a couple years, and I couldn’t find that screen name used on any other site, although he had a lot of really interesting things to say about the film. “Mastermind” decided not to be in the film, Rob Ager was working on his own DVD, and I wouldn’t necessarily exclude something if it was out there if I thought people were being genuine, and if it got under my skin and I found it persuasive and interesting.

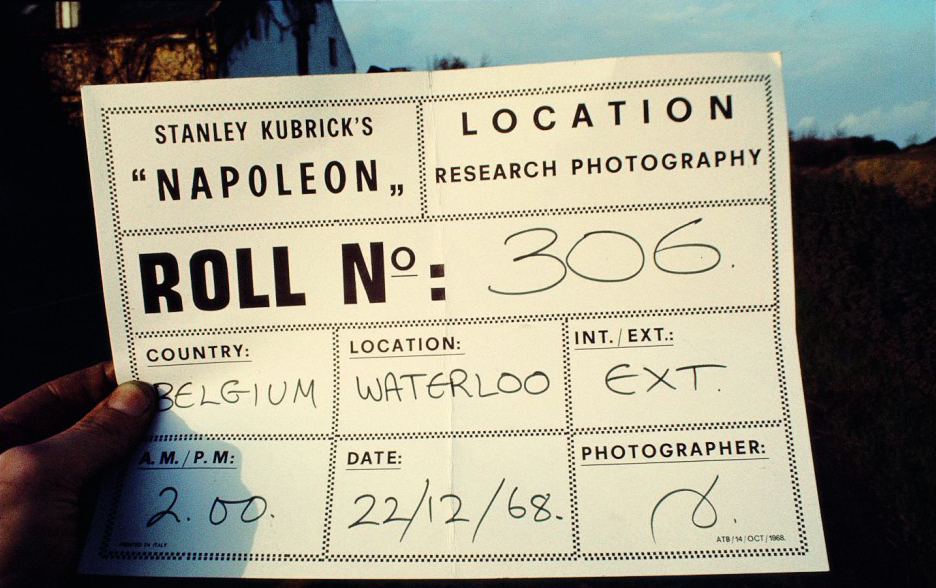

But why The Shining? Why not Eyes Wide Shut, or Full Metal Jacket, or A Clockwork Orange? Why not 2001? It started with The Shining when Tim sent me that Weidner article, and there’s something about The Shining that makes this kind of stuff seem very plausible. There are these really weird choices of music; a lot of the names of the pieces have sort of biblical illusions. There’s The Dream of Jacob, for one. And there’s a lot of air and space, scenes where Jack [Torrance, the tormented writer played by Jack Nicholson] is just staring off into space. These bold patterns that you can read from a mile away. It seemed very plausible that there was stuff in The Shining that just agreed with me right away, and we looked at other stuff like 2001 and Eyes Wide Shut, but there didn’t seem to be as much written about these other films as The Shining. And then The Shining has these really nice parallels to Room 237. They’re both movies about small groups of people that are trapped in this imposing architecture that’s kind of chilly.

Clarify the reason Kubrick changed the number of the room from 217 in the book to 237 for the movie. In the book, famously, the hotel room was 217; in the movie it’s 237. In an interview with [French film critic] Michel Ciment, Kubrick said that he changed it at the request of the hotel, which I assume would’ve been the Timberline, where they shot some of the exteriors, because they didn’t want that room to have a bad reputation. I’ve never heard that that story was investigated terribly thoroughly, and of course it also raises the question of, well, so maybe you couldn’t have used 217, but there’s infinite numbers it could’ve been. It could’ve been 342, it could’ve been 299, but 237 does have sort of an odd quality to it — like maybe it’s a prime number but it’s a very unsymmetrical number — that it seems plausible that it might have some significance. And Jay Weidner, who talks about the meaning of that number in particular, said that story wasn’t true. He said that he called up the hotel, which according to Kubrick’s story said they didn’t have a 237, so there was no harm in giving that room number a bad connotation. Jay said they do, in fact, have a Room 237.

Why would they lie? Why would they lie? Or why would he lie? Or why would Kubrick lie? Kubrick might’ve lied because he wanted to be coy about his reason. The hotel could’ve lied when Jay called them because they’re sick of answering questions about The Shining, or Jay could’ve lied because it was important to him that this hotel room number mean something, or the hotel changed its numbers. Or they could’ve been telling him the truth in this conversation, but it not might not have been the truth back in 1980. You can look at any of these questions and there’s always a good half-dozen possibilities.

Kubrick lived almost a good twenty years beyond The Shining. Did he ever address any of the theories? As far as I knew, he never addressed it, but it seemed like it wasn’t the type of thing that he would’ve addressed. I heard stories that after 2001 people would tell him their ideas about what the movie was about, especially the final act, and he was very interested in hearing it, but wouldn’t comment on it. There was an interview I read with him where he said the Mona Lisa wouldn’t have been improved if it had a little plaque underneath it saying she’s smiling because she’s thinking about a past lover. Which implies she is smiling for a particular reason — but that Da Vinci was well advised to keep that reason to himself.

Have people approached you and said, “You’re missing an obvious theory,” and proceeded to give your their own? I’ve got a couple, but it hasn’t been an avalanche. Some people are familiar with a lot of the stuff that’s online and have said, “How come you didn’t say this thing that Rob Ager said, or this thing that Mastermind or other folks mentioned?” The interesting ones are people who have their own ideas, like, “How come you didn’t talk about this movie in relation to feminism and gender studies?” And I was like, “How do you mean?” And then, when they explain it, it’s like, “That’s really interesting. Where were you a year and a half ago?”

Are you in general a conspiracy theorist? Not really. I’m always kind of interested to hear alternative points of view, but I wouldn’t consider myself one.

Overall, do you want the film to be taken strictly as entertainment, or for an audience to give the theories serious consideration? I hope those two ideas aren’t mutually exclusive. When we set out to do

something which was in some ways an experimental documentary about the symbiotics of a thirty-two-year-old horror movie, I thought making it kind of entertaining would help that go down. (Laughs) I was talking to someone just a couple of hours ago about the film, and he was concentrating on the continuity errors and remarking that Kubrick was too much of a perfectionist to have made mistake after mistake after mistake. Certainly not all of them, and there could’ve been a handful of them just from the process. In some ways I’d like the film to be about things above and beyond The Shining, the way people make sense of art and music and the world around them. But The Shining and Kubrick are very fascinating, precisely made, mysterious objects that are worth investigating specifically. There are folks who have made fun of one or two of the ideas of the film, but have been kind of persuaded by others.

Why do you think Kubrick holds this fascination for film lovers, historians and critics? He’s sort of the perfect intersection of style and substance. His movies look great, and have created one iconic image after another after another, but they also work as stories and metaphors. Even Barry Lyndon, which at one point made me get poked in the ribs, I love it. The last section, with the duel with Bullingdon, is so incredibly suspenseful, that it may be a slow ride getting to that point, but my God, it’s incredibly suspenseful. His films are beautiful to look at, they’re great dramas, they all lend themselves effortlessly to great metaphors.

You eschewed using the traditional talking-head approach in your film. What was the reason for that choice? I come more from an experimental, collage/remix background than I do a traditional documentary style. I also am not necessarily a big fan of them in a lot of cases; sometimes you’ll see this great montage, and then you’ll cut back to a talking head and we kind of come back down to earth. I just wanted to stay in this bigger, visually driven land of ideas. It was kind of a lo-fi way we did it anyway, and I would just mail people digital audio recorders and talk to them on the phone and then they’d mail the recorders back to me when they were done.

How many actual non-Kubrick films did you have to cull from to find the right clips to use? Seventy-five, a hundred. It was a lot of work, but I was pretty happy doing it.

Did you actually film an audience watching the movie? No, that’s all licensed from Lamberto Bava’s 1980s horror film Demons, with Demons 2 in there for a second. It’s great because the crowd is dressed for the early ’80s, their performances are amazing for what we’re doing, and Demons is actually kind of a great example of what we’re talking about because it’s the ultimate movie where the line between the movies and reality gets blurred. Creatures come out of the screen and attack people in the movie theater, so people who get that actually can appreciate the metaphor for the bigger picture.

In your film, [musician and blogger] John Fell Ryan talks about playing the film simultaneously backward and forward. Have you ever tried it yourself? I had to assemble that in order to recreate it. You have the movie playing normally, and then you take another copy of the movie and you put it in reverse motion and dissolve it 50 percent. You play it on Final Cut. The novelist Jonathan Lethem told me about it. I was thinking about interviewing him for the movie, but it didn’t work out, but he said there’s this guy in Brooklyn who’s showing it forwards and backwards. So I was very interested in that, and it was this great kind of subtext to the movie about the way people’s viewing habits had changed. In 1980, you had to watch it in the theaters, and then it went to VHS and DVD and Blu-ray, but kind of the ultimate step is now, with digital technology, people can manipulate the film in order to look at it differently.

They played it at Fantastic Fest, and that was amazing because I was expecting there to be a lot of great visual juxtapositions that Ryan was talking about, but it also works narratively in these amazing ways. The first half plays as a black comedy, the second half plays as tragedy; it’s centered on the point where Hallorann [the hotel’s head chef, played by Scatman Crothers] is getting the message from Danny [the young son of Jack and Wendy Torrance, played by Danny Lloyd], so you kind of see the whole feedback for the movie disappearing into his head and it emphasizes the moment when he decides to go to the hotel because we’ve seen the whole movie already, it’s like he knows the whole movie already, and knows that he’s going to die, which makes his decision to go that much more meaningful. There’s things like when Lloyd, the bartender, says, “Women. You can’t live with them, you can’t live without them,” the nude woman from Room 237 blurs into the scene. It’s a movie about people who are haunted by the past and can see the future.

Couldn’t this all just as be an incredible coincidence, too? Sure. But it is an incredible coincidence.

The story about Kubrick supposedly having helped fake the Apollo moon landing has been floating around for years, and that in The Shining he makes his mea culpa for it. Do you personally hold any belief in it? I’m going to have to play coy for the interest of people being able to watch Room 237 objectively. Certainly if anyone was going to do it, having been the guy who had just shot the most realistic surface-of-the-moon sequence for 2001, and was consulting with NASA in order to do that, he would be the obvious choice. Don’t they say that On the Waterfront was in some ways a similar confession, or sort of metaphor for the blacklist? There would be a precedent for that sort of thing.

When The Shining came out, the reaction was very polarizing. Why do you think that was? It might’ve been because of the popularity of the book. You got me. I’ve always thought the movie was amazing. I’ve seen some of those negative reviews. On YouTube there’s a funny one of Gene Shalit kind of taking it apart. a lot of his movies, certainly 2001, might’ve gotten some mixed reviews at the beginning, and certainly Eyes Wide Shut is gaining popularity in hindsight.

Is that because of the Kubrick mystique, or that people just misjudged things? I would say because they misjudged it, because The Shining is an amazing movie. But it could be the result of heightened expectations. You’re thinking, “This is the new film by the greatest filmmaker of our time,” and sometimes it’s impossible to live up to those expectations, but I’m just speculating. Certainly the folks we talked to in 237 think it’s because The Shining is too complicated to really understand and appreciate in one viewing.

But what about those who felt it wasn’t a faithful adaptation of the book? Maybe they didn’t like some of the ambiguity in the film. Maybe a general audience wants things that are more clearly explained because things that are a little more ambiguous kind of claw, keep at you for awhile, and a lot of horror movies, and a lot of supernatural horror movies, say, “Here’s a twist ending, now you get it!” and you’re comforted in a way. Certainly this movie ends on that black-and-white photo and that date, meaning it ends on a question mark, not

an exclamation mark. People aren’t necessarily sure of what is the implication of that photo at the end, or certainly that date.

Actually, there’s two schools of thought on that. One is that Jack’s always been there, or that he’s been absorbed. The question is, “Was he always in that picture, and they just never knew it, and they would walk past it every day, or does he sort of appear in that picture because of the actions in the last act of the movie?” That date, July 4th, 1921, is so prominently featured that you wonder, “Well, it’s American Independence Day, what was going on in 1921?” And that date where the party was so clearly referenced in the first part of the film. That’s kind of ambiguous, and people have always speculated, “Are there really ghosts, or is just Jack’s insanity?” The Kubrick film gets kind of a hard rap because of how much they changed the book. I recently re-read the book. and there’s lots of passages of dialogue that are the same. Almost every movie changes the original book pretty dramatically.

Do any of the theories hold up with the TV remake of The Shining? Not really. Most of the people we interviewed, I don’t think even saw the television version. They also see the book as interesting, but not necessarily … if Kubrick’s Shining is the Bible, then King’s book is apocrypha. Interesting, but a little bit dangerous and unreliable.

King is not a fan of the original film, but has he ever talked about the theories? He might’ve softened on it a little bit over the years, but I’ve never heard him talk about the theories. Certainly now that 237 is getting played a little bit, he’s probably the person I’m most excited to hear from. In a way, this is kind of a game of telephone — if Stephen King wrote this book, and then Stanley Kubrick kind of thought about the book and reprocessed it and changed it into his film, and then these people saw Kubrick’s film and they take something else out of it, and then it’s back to King, it’d be an interesting way to close the circle.

Since the film has been playing festival circuits, have you had anyone famous approach you and offer their take on it? The short version is no. The celebrities I’ve talked to about it were Lee Unkrich from Pixar, who directed Toy Story 3 and co-directed Monsters, Inc. and Finding Nemo, he’s as big a fan of The Shining as any of the people we interviewed. He owns like one of the axes from the movie. He’s put little tributes to The Shining in the Toy Story movies. There’s a vehicle that has 237 as a license plate, carpet patterns from the movie appear on the wall and behind one of the characters. He writes a blog called “The Overlook Hotel,” where he posts nothing but Shining trivia.

Who’s the other celebrity? Alec Baldwin. He’s really into Kubrick, and we met him in Cannes because he wanted to see the movie, so he came to our little party. He didn’t say, “Yes, I’ve seen all that stuff.” His tweet about it was “Bee-fucking-zarre.” I didn’t get to have an especially long conversation with him after the fact, but he watched the whole thing and he thought about it.

What opportunities have presented themselves as a result of Room 237? I’m getting meetings and I’m encouraged that I’ll be able to do the next one during daytime hours (laughs). When I was working on this film I was teaching an editing class, and taking care of a baby, and I was doing freelance editing projects. I directed a music video, but the biggest part of 237 was done on weekends and at night.

Do you want to stay in the documentary field? I want to branch out. I didn’t start in the documentary field, but this was something that I was just personally very interested in. I loved these ideas about The Shining, they blew my mind, they made the hairs on the back of my neck stand up when I read them in the middle of the night. I thought, “Maybe if I can sort of navigate through the most compelling ones, and put them together in this audiovisual style, other people would have a similar experience.”

One of the people interviewed said basically that, while it’s the author’s intent to create, the ultimate interpretation is left up to every one else. Why do you think that’s true, because sometimes, like Freud said, “A cigar is just a cigar”? It’s great that you bring that up, because John Fell Ryan was talking about that phrase a couple of weeks ago. He said that the reason that’s worth saying is because usually a cigar is not just a cigar — sometimes it is, but usually it’s not. The quote you’re talking about is Geoffrey Cocks, the history professor near the end, who says people who are familiar with postmodern film theory know that author’s intent is only part of the picture, and those meanings are there whether the original creator was aware of them or not.

237 wants to ask the question of how important is the author’s original intent versus what the audience brings to it, without necessarily answering it. I see a movie like Starship Troopers, and it’s clearly a satire about the post-9/11 war on terror, only it was made in the late ’90s, before so many things it seems to be about happened, although the themes kind of recur in history. Plus, in the case of most films, the author’s intent is often difficult to know. Maybe, like Kubrick, they don’t want to talk about them, or if they talk about it in public, they could be coy, or they might not be able to express themselves as well in an interview as they were in making the movie. So author’s intent is important, though it’s not always knowable.

Metaphors that people find compelling activate a piece of art, no matter where they come from. There’s actually this whole radical thing called synchro-mysticism, where people are doing these kind of things with pop culture, and there was this weird connection between Dr. Seuss’s Green Eggs and Ham and The Innocence of Muslims, that YouTube film that they said was in part responsible for the violence in Libya. This guy found like half a dozen connections between the two, and what the implications were aren’t entirely clear, though it is certainly kind of disturbing. It’s like what John Fell Ryan says near the end [of Room 237], where it becomes kind of a trap, where the more you look for clues, you keep finding them. What does that mean?

Did you ever visit the hotel they used to film the movie? Which one? There were three. The Timberline is the exterior from the helicopter shot. The Ahwahnee was the model for the lobby inside, and then the hotel that Stephen King stayed at on the closing day before they shut for the winter that inspired the book was the Stanley Hotel, which is a funny coincidence.

There’s another one! And the coincidences start hitting Room 237, too. We played at a theatre in Sundance that was on Sidewinder Drive, which is the name of the road in the book that leads to the Overlook Hotel. They keep happening, and it’s like one is a joke, two is interesting, and three, four, five it starts to get very persuasive.