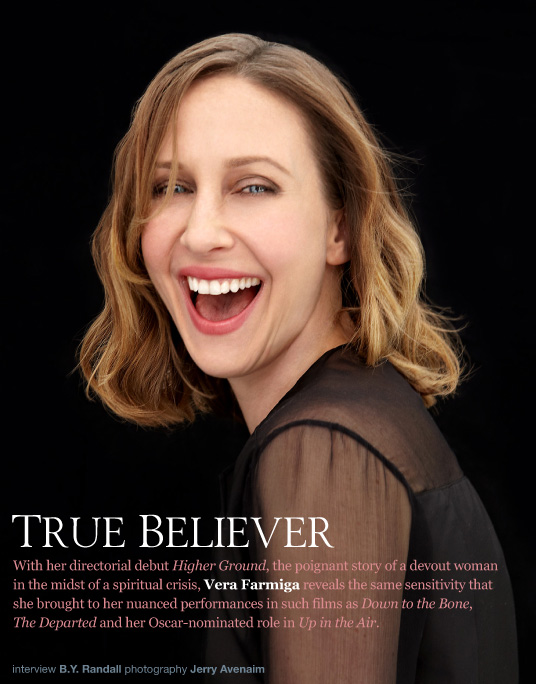

Despite such obstacles, the neophyte filmmaker excelled on both sides of the camera, and when it was done, Higher Ground was chosen for the dramatic competition at this year’s Sundance Film Festival, where it earned glowing reviews and was acquired by Sony Pictures Classics.

Farmiga did not originally intend to direct Higher Ground – or any other film, for that matter. On the contrary, she was content to devote herself to acting. But when financing for the project proved difficult – not surprising given its non-commercial subject matter – she agreed to give it a go. Although she had no prior directing experience, she had just received a best supporting actress Oscar nomination for her performance in Up in the Air, which made her sufficiently bankable for the producers to raise the money.

Fortunately for Farmiga, she has worked with some of the most acclaimed directors in Hollywood – including Oscar winners Jonathan Demme (The Manchurian Candidate), Anthony Minghella (Breaking and Entering) and Martin Scorsese (The Departed), and Oscar nominee Jason Reitman (Up in the Air) – and learned from all of them. But when she began preparing Higher Ground, the filmmaker she reached out to was Debra Granik, who brought a raw, dirt-under-the-fingernails authenticity to Farmiga’s breakout film, Down to the Bone, and, more recently, to Winter’s Bone, which earned four Oscar nominations, including one for best picture.

Born in New Jersey and reared in a Ukrainian community so tightly knit that she did not speak English until age six, Farmiga began performing in her teens when she toured with a Ukrainian folk-dancing company. Although her poor vision led her to consider a career in optometry, she opted to study acting at Syracuse University, and soon after graduation found work on the New York stage. Her first major break came in 1997, when she was cast in the short-lived television series Roar, starring a young Heath Ledger. Although she worked steadily in TV and features from that point on, it was not until Down to the Bone, in which her ability to vanish into a role suggested the range of a budding Meryl Streep, that the industry took serious notice. Her performance as a wife and mother with a cocaine habit was at turns both fragile and formidable, and earned her best actress awards from the 2004 Sundance Film Festival and the Los Angeles Film Critics Association, as well as marked a turning point in her career.

Since then she has held her own opposite such leading men as Leonardo DiCaprio and Matt Damon in The Departed, George Clooney in Up in the Air, Keanu Reeves in Henry’s Crime and Jake Gyllenhaal in Source Code, and next year she will be seen in Safe House, an action thriller with Ryan Reynolds and Denzel Washington. But even though her star has risen in the Hollywood firmament, Farmiga has remained largely a cipher to the public, preferring to make her home far from the prying eyes of TMZ and Us Weekly in upstate New York, where she lives with her husband, son, daughter and four goats.

In an interview a few years ago, Farmiga expressed her wariness of Los Angeles in a quote that has followed her ever since: “I can’t do Los Angeles. I’ve always been the anti-Barbie. I don’t want to be in a place where almost every woman walks around with puffy lips, little noses and breasts large enough to nourish a small country.”

As a bumper-sticker-ready jab at L.A. and an assertion of her willful authenticity, the remark resonated in a way that few celebrity sound bites do, which explains why some portion of it turns up in almost every story written about her – including this one. In retrospect, it was a flippant comment not meant to define her. But given the distance she keeps from the industry, and her suspicion of its trappings, Farmiga’s spontaneous candor may have revealed a greater degree of self-awareness than she realized.

Not as widely quoted are the words Farmiga spoke immediately afterward: “As a kid I wanted attention, so I started praying for glasses because everyone had ace vision in my family. Then one day my eyes started going bad and never stopped.” Although it drew little attention at the time, it is an intriguing anecdote in light of her powerful work in Higher Ground – both as an actress and as a director – and the even-handed manner in which the film grapples with matters of faith and belief, which she delved into at length when she spoke with Fade In shortly before the August 26 release.

Higher Ground is your first foray into directing. Had it always been a goal? Never. I never thought about it. And I may or may not do it again. There are a lot of opportunities coming my way as a response to the film. But there are great opportunities coming to me as an actress as well, and I love the collaboration with different directors. So I’m not in a hurry to direct. If another opportunity presents itself that motivates me, touches me in a profound way… I was profoundly touched by Carolyn’s memoirs and her story. I was challenged in a psycho-spiritual, intellectual, emotional way. And when that happens with you when you read something, whether it’s a book or a script – I felt slain in the spirit. Not even sure why, but I did. And when something touches you that deeply, you act upon it. Once I started collaborating with Carolyn, and further developing the script, our senses of humor became part of the equation, and our sensibilities as storytellers. We delight in the same kind of ideas. There was a shorthand in me directing it; in defending the tone. I didn’t write it, but I developed it with her and I steered her in the narrative, which was when a lot of me entered the script. And instead of telling someone else how to direct it, it was just shorthand to just do it.

How does it feel to be a newly minted hyphenate? [Laughs] I’m proud of the film, so it feels good. I love this story every time I see it. I have a deep affection for what we’ve achieved in the story. It is deeply personal so this experience keeps going for me. Still not sure why I made it… it was a very strong, strong sense of having to do it. It’s not about me, but there are a lot of bits of pieces and perceptions of mine in there. There was a higher calling for me. It took me by surprise, directing. The hyphenation is a surprise. I’m not entirely comfortable with it. Maybe until there’s another film or so under the belt. I really felt that the call to directing was by necessity and/or default. It wasn’t being financed without me at the helm.

So the financing only came together because you stepped up? Yes. I would say only with that, only by virtue, with me at the helm. This was a year and half ago, so it was right after the Oscar nomination, and there was a certain amount of luck and attention and respect that comes with that – particularly with all the attention with Up in the Air, and the accolades at that time. In my life there was a confidence that came with the idea. I suppose that the people at that point – my manager, and Carly Hugo and Matt Parker at The Group Entertainment, and three of my producers – they just liked my ideas for the approach to the story.

What’s been the reaction so far to the film? There are radically different reactions to it. I delight in two very different reactions. The believers who actually are very excited to see a fully dimensional portrayal of belief and doubt, and then the agnostics and/or atheists that have an empathy for this woman’s journey even if they can’t relate to faith at all on a religious level. And then there are ones that don’t give a flying fuck about spirituality or delving and deciphering what holiness means to you. I’m asking a lot with the film. We can all relate to the idea of community, and the need to belong to a community, expressing individuality within that community, it being a very flawed community – but it being a good community.

“A moment of sheer panic set in when I was embarking on my second trimester. It was a combination of hormones and lack of sleep, because I had just taken a break from the pre-production schedule to go shoot Source Code, so my focus was completely on a different project.”

“There are moments in my life… These transitional phases of death and birth in my life; My first divorce, which was a death, when I became a mother, when I met my husband, Renn. Those are the moments when your heart is broken…or broken up. They have to do with not being broken down, and where enlightenment comes, because your heart and your mind are open.”

What was the hardest part about the shoot? A moment of sheer panic set in when I was embarking on my second trimester. It was a combination of hormones and lack of sleep, because I had just taken a break from the pre-production schedule, which I think was four to six weeks, to go shoot Source Code, so my focus was completely on a different project. After Source Code, I had lost about two weeks’ worth of time, and I started to panic, asking, “Can I really do this?” I thought about everybody else’s character arcs and not mine. In talking to actors and wooing actors, I had gotten into the other characters’ headspace, but didn’t even know how to approach mine. I felt disabled, and I felt I needed the support and reliance of a director, and I emailed [Down to the Bone writer-director] Debra Granik the script and said, “Take a look at this. We’re shooting in six weeks!” Debra responded she’d be there to mentor me through it and encourage me through it, but her process as a director is to be enmeshed in the community and she had to gather details for a very, very long time. But I knew I’d have Debra’s support, as Down to the Bone was a very formative experience for me as an actress.

How was that film a turning point in your career? It was a springboard. I would not be sitting here talking to you. I wouldn’t have done The Departed had it not been for Down to the Bone. I wouldn’t have done Up in the Air. Down to the Bone has always been the reference film for why directors hire me.

When you announced that you were going to direct, what was the feeling among family, friends, representatives…? Very supportive. Extremely supportive. Had I encountered anything but… I have a good sense of self and [my] limitations and abilities. I had my own confidence about it, but also I had this tremendous support. [The] ideas that I had verbalized at that point were some strong ideas, and they just liked the ideas.

There was a moment of panic because we were thrown into pre-production because the financing came together like this. [Snaps fingers] About six miles away from where I live in upstate New York there happened to be a new production company that was going to finance several films, and we were the first on their roster. At the initial meeting with [producer] Claude Dal Farra, I fainted in his presence. When I came to, I told him, “I’m pregnant, by the way.” And he goes, “We better shoot this before the baby bump emerges.” So we were thrown into pre-production, and it all happened rather quickly. We did some work on the script, and rearranging, and when the script was almost there I sent it to John Hawkes first. I said there were several conditions [before] I would direct it. I would only direct it if Michael McDonough were my cinematographer, because where I felt disabled and handicapped as far as not having gone to school, and only operating from instinct and intuition as a storyteller, and not having technical savvy about cameras and equipment and angles and lighting, I wanted him to bolster me there. I was emphatic about letting me have the actors that I want: “I don’t want to talk about names, I want to talk about who’s right for the role. I want to use my sister [Taissa Farmiga] to play me.” She doesn’t want to be an actress. She’s never acted in anything aside from a fourth grade play, which she botched up horribly.

We were wondering where they got someone who looks so much like you. I just find her face so exquisite and so transparent, and she possesses, as a young lady, the qualities that I was looking at, which are strength and vulnerability in equal measure. She fit the bill. So I said, “These are my conditions.” And I was fortunate to work with producers that really believed in my vision of things, so they gave me pretty much everything I wanted, within reason.

One of the funniest bits in Higher Ground is the running gag of the young Corinne always being stopped when trying to check out Lord of the Flies out of the library. What books were verboten when you were growing up? Are You There God? It’s Me, Margaret. I remember that was the one book for whatever reason. It was an age thing, and I had to sneak it from my mom for whatever reason. I don’t remember why. I was too young.

How close did your own upbringing affect the way Higher Ground turned out? I would imagine quite a bit. I’m not comfortable talking about it, in a way. People then don’t experience it in their own personal way if I reveal too much. I’m not sure. That’s why I made a film about it, because there are a lot of murky feelings and notions and perceptions. There’s a whole lot of me, and very little of me at the same time. There’s a whole lot of Carolyn Briggs and very little of Carolyn Briggs in it. A large part is fictionalized, but very poignant, and to say which ones are me and which ones aren’t… . There’s a great, personal kind of envy of people with great faith. My father is a man of great faith, and I envy him, and I marvel, marvel at the man for being at such great peace and wisdom and selflessness. [Loudly] Joy like I’ve never known in anybody else! A perpetual innocence that he possesses unlike anybody I’ve ever met. He’s a powerful man. Great.

What’s his profession? He was a systems analyst for computers and was a victim of ageism with his company. The company downsized several times, and was bought out, and finally he got axed because it’s so much cheaper to hire younger. Now he does landscaping maintenance for elderly communities, and he loves it, because it gives him a chance to chat with people and get to know people and spend time in nature. He’s never disappointed. Everything is an opportunity for my dad. Incredibly positive. Joyful. Joy in the truest sense of the word. So I marvel at it, and he taps into something much larger than himself. [Laughs] He’s very much on a guided tour of the universe. I’ve always wanted to decipher that and understand it in the same way and the effortless way he does because it’s so genuine. I’m sure there’s a large part of that in there.

By the end of the film your character, Corinne, has reached a sort of enlightenment about where she wants to go with her life. What’s been your experience in your life with something similar? Many, many times there are these moments in life where, like Carolyn, you have to remove yourself from everything you hold dear. In Corinne’s case, she has to remove herself from her kid, her husband, the church in order to have her own protection. There’s this very painful moment of doubt and insecurity and questioning, and allowing the pain of all of that, and the fear, and the not knowing. I’m going to learn something about myself here, because this is so yucky, this is so painful and uncomfortable. I guess there are moments in my life, yeah. My first divorce, which was a death. It’s death and birth. These transitional phases of death and birth in my life; when I became a mother, when I met my husband, Renn. Those are the moments when your heart is broken…or broken open. They have to do with not being broken down, and where enlightenment comes, because your heart and your mind are open.

Your film is very reminiscent of The Apostle. It was a huge reference to me. It’s one of my favorite films. I’d say it’s one of my top five.

Why do you think Hollywood is so reticent to tackle films about faith? They are, but films about religion exist, but in a very black-and-white perception and account of it. They are made to convert, and they’re either pro-, or the anti-religious films that are cynical and there’s no pendulum between the two. It’s just easier to make a concrete movie about it. [Higher Ground] is not about that. It’s a film about embracing the gray. It’s complex.

How do you go about marketing Higher Ground? Better talk to Sony about that, I have no idea. [Laughs] I read a New York Times article recently talking about how in times of crises and desperation, politically, socially, that’s when people tend to fall on their knees – despair and poverty, in times of war. People are longing to feel the breath of God on their face, but very frustrated with organized religion. That was the gist of the article, and probably a good target, and that’s a pretty vast spectrum. But I don’t think it should just be reduced to a film about a relationship between a woman and God, because that’s not the film I was making. Sure, it’s obviously a story about a woman and her life and a fundamentalist community, but it touches deeper about yearning on every level as a mother, as a daughter, as a sister, as a best friend, and a member of the community. For intimacy, all those relationships, and to be genuine to yourself in all those relationships. It’s the story about a woman who takes a very long time to find a voice, and who’s been diminished her whole life. It’s a hard one to talk about. I’m drawn to the story in the same way I was drawn to Alice in Wonderland when I was a child. Awakening, in every possible way, she’s not only looking for spiritual enlightenment and spiritual awakening, [but] sexual as well, and emotional, intellectual – on every level. She’s searching.

What is the difference between faith and religion? The difference between faith and religion is…[Long pause] This is a question I’d love to sit on. Oftentimes a lot of things in my heart don’t make it out to my tongue efficiently, and this is such a beautiful question that I have to think about. [Pause] The difference between faith and religion. Religion is man-made, faith is a state of being. Faith means a couple of different things. There’s not one definition for faith. It’s tricky in that way. Faith means a lot of different things to a lot of different people. Faith is belief, it’s perseverance, it’s the way we sustain ourselves. It’s hope.

You don’t need religion to have faith. No, no you don’t, but you need faith to have religion.

What’s so great about Higher Ground is that it’s a clear-eyed view of faith, and not making judgment and not preaching. No, no, that wasn’t the objective. Those kinds of films are intended to convert. They’re proselytizing films. That’s not the kind of film I was making. Religion is like a knife, you can either use it to stab someone in the back, or you can use it to slice bread. There’s a duality. There are parts that’ll make your blood boil, but there are parts that also make you find commonality. [Laughs] I’m trying to find commonality. I’m not judging Christianity. The mission of the film is not to determine whether Jesus Christ is the way, the truth, the life. That’s not the point of the film. It’s not a religious film. It’s a film about religion. It’s all about family, attaining wisdom, transcendence, identity, courage and having the courage to step out of the roles we create for ourselves.

Which leads to a quote that was attributed to you in an early interview that you viewed yourself as the “anti-Barbie.” You know, I said that in one of my first interviews, and it was a leading question. [Sighs] It was taken out of context. I was talking about myself as a child… I don’t remember the thought processes behind that statement. Do you know the quote?

It was something like, “I consider myself the anti-Barbie. I don’t walk around with puffed-out lips and gigantic breasts.” Proportions. Gigantic proportions. I was speaking about L.A., and my comfort level in L.A. The conversation started that I’m so focused on the physical when I’m in L.A. You cannot [not] be. My concentration is skewed when I spend any length of time here. I feel like my focus changes and I become so much more concerned with appearances and spend so much more money here on fashion… which I love. [Laughs] It’s important, but not as important as it gets as when I’m here. I like myself better when I don’t focus on these things.

“It’s not a big deal! Everybody has goats. The goat thing happened because I do my own weed whacking, and my own lawn. It’s meditative. It’s therapeutic. In my downtime, I love landscaping. I’ve worked very hard for the last 7 years to make it look like you stepped into an Edith Wharton novel.”

“I read a New York Times article talking about how in times of crises and desperation, politically, socially, that’s when people tend to fall on their knees – despair and poverty, in times of war. People are longing to feel the breath of God on their face, but very frustrated with organized religion.”

You live in upstate New York. Please explain the goat thing. It’s not a big deal! Everybody has goats. The goat thing happened because I do my own weed whacking, and my own lawn. It’s meditative to cut a lawn and to weed whack. It’s therapeutic. In my downtime, I love landscaping. I love weeding. I’ve worked very hard for the last seven years I’ve lived there to make it look like you stepped into an Edith Wharton novel. But I love doing it myself, and there’s a rocky patch of soil that I was sick of weed whacking and I couldn’t run a tractor over it, so we said, “Let’s get some vermin in to keep the chow down.” We couldn’t find sheep, and my mom called and said, “There’s some goats.”

Angora? These were Nubians. Angoras came later. First were Nubian. She drove them up. The thing with goats is, they’re browsers, they’re not grazers. I should’ve gotten sheep, because sheep like to graze. Goats prefer to reach up for their food, and they won’t eat what they trampled on. So I was kind of stuck with them, but they’re lovable creatures, they’re highly trainable, they’re highly intelligent.

So the story about you raising Angora goats is out of proportion? Raising? I have four goats! My husband did have a sweater made from the sheep.

What about a marketing empire to be made from the sheep? There was a spell before Up in the Air where I was a little bored, and I thought I needed something else. Something else where I could see the fruits of my labor. And my hobby was to spin wool – and, yes, at one point we did want to breed the goats. [We] thought about it, but we never followed through. Totally blown out of proportion. Yes, I shear their wool, and I utilize it, and I make my husband’s sweaters. That is fascinating to some people. I’m from Ukrainian peasantry, it’s just what we do. In another life I would’ve loved to design sweaters. I’m good at designing big, cozy sweaters. It’s a hobby. To some people, the provincial lifestyle is like living on Mars. So the city folk come up to interview and see the goats, they see us walking with the goats, they see my spinning wheel. There are buckets of wool everywhere. So, no, I don’t have a herd of goats. I have four of them. Not even four. We just lost one. But the Nubian ones are champion milkers, and they’re really beautiful goats, and they deserve to be bred. At one point, we entertained going bigger with the herding – absolutely we did. But then I gave birth to my children.

Settle another comment that you turn rejected scripts into bonfires. That’s another thing! They make me out to be a real anarchist. Yes! But what do people do with scripts here that are no good? Shred ’em, right? We don’t have a disposal service up there unless you pay a lot of money for it and you take your trash to the transfer station. That means you have to be really conscientious about separating into metal you can recycle, and plastic and paper. A lot of my scripts come watermarked [and] are top secret with my name on them. And a lot of them, yes, do suck. I could shred them, it’s just a lot of shredding, so yeah, they make it to the burn pile. There’s an enormous burn pile. They get burned up, and then the ashes I throw in the vegetable garden. It’s great fertilizer.

You’re allowed to burn on your own property? You have to get a permit. It’s not a big deal, especially if you’ve got connections. [Laughs] Yes, it’s scripts that more often than not I’m repulsed by or disheartened by.

Has there ever been a project you passed on that you regret? I haven’t passed on anything that I… oh, yeah, but I don’t regret it. It wasn’t an offer, but I met Darren Aronofsky for The Wrestler for the Marisa Tomei role. I didn’t see the coupling of me and Mickey Rourke. It wasn’t an offer by any means, so it’s not fair to say. It was just a sit-down meeting.

How often do you get something where you go, “Why did they send me this?” All the time. My representatives know my taste, and they send me a lot of things just to know what the climate is, to know what’s out there and just to be informed. And I surprise them time and again with risks that I take, so they like to send me everything. They have a great sense of what will move me and motivate me. I don’t really pass on much. Actually, I take a lot of the stuff that’s offered. Funny enough, there’s been a lot of offers and a lot of talk about my “choices.” [Laughs] I guess to a degree, yes, I do pass. [Sighs] I just think those things are like magnets. The universe draws things to you that are meant to be. [Laughs] I believe in magnetism.