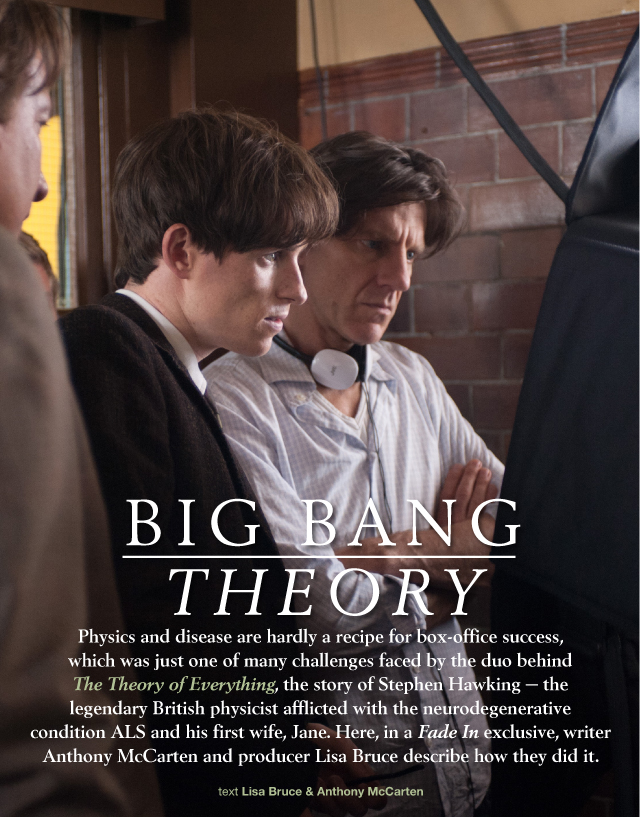

n 2004, long before we had even secured the rights to Jane Hawking’s book, Travelling to Infinity: My Life with Stephen, Anthony was so captivated by Stephen and Jane’s story that he wrote a screenplay adaptation. It was a risk, but worth it, because he knew that even if he never got the rights, he would learn a lot from the process, and it would make him a better writer.

n 2004, long before we had even secured the rights to Jane Hawking’s book, Travelling to Infinity: My Life with Stephen, Anthony was so captivated by Stephen and Jane’s story that he wrote a screenplay adaptation. It was a risk, but worth it, because he knew that even if he never got the rights, he would learn a lot from the process, and it would make him a better writer.

It was such an intoxicating, powerful and even unprecedented brew of elements — the birth of the universe, the nature of time itself, coping with the loss of the use of your body and voice, an unorthodox love story and, finally, a triumph over extreme adversity — that Anthony saw it as a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity, regardless of the outcome. In the end it took eight years to secure the rights, but the perseverance paid off. A little faith went a long way.

Anthony took the first steps toward securing rights in 2004, when he visited Jane, arriving as a stranger at her door. She let him inside her home, and he outlined the movie he envisioned, which would comprise three interwoven threads of narrative: 1) a love story, 2) the horror story of what ALS does to a body and 3) Stephen’s breakthroughs in physics and the writing of his famous book, A Brief History of Time.

Jane was sufficiently encouraged by the pitch to allow him to write a draft, and she agreed to talk again once she had read it. Surprisingly, he was the only suitor; for some reason, no one else had seen the potential of approaching Stephen’s life tangentially, through Jane’s story. Thus began an eight-year conversation between her and Anthony in which he insisted on script control. Jane, to her credit, never tried to soften the story, even when he added equal measures of Stephen’s perspective to the script, to balance the narrative. Her slowness in agreeing to grant us the rights had nothing to do with the script, but rather with gradually growing into the idea of a major movie about her life, a scary thought for anyone. The time had to feel right for her and for her family. It couldn’t be rushed.

“In 2005, Jane signed a ‘shopping agreement,’ which allowed Anthony to pursue investors. But interest was scarce. Most people saw it as a film about physics and disease.”

In about 2005, Jane signed a “shopping agreement,” which allowed Anthony to pursue investors. But interest was scarce. Most people saw it as a film about physics and disease — a marketing challenge, to say the least.

It was a frustrating process, but creatively, the extended interregnum allowed Anthony to further sharpen the script and to find a great producing partner when he partnered with Lisa, who is represented by the same agent, Craig Bernstein at ICM.

As an independent producer, Lisa is always looking for stories with gravitas and humor that move her emotionally. When she read an early draft of the script, it struck her on all counts, and she jumped in immediately. But she knew that finding legitimate financing was impossible without the rights to Jane’s book. So, she joined forces with Anthony and spent the next few years building Jane’s trust.

While we waited on Jane, Lisa continued to give Anthony notes, and the script continued to evolve. Working together, we were able to really push, finesse and fine-tune the story to bring forth the various layers and colors of Stephen and Jane’s remarkable journey.

Finally, in 2010, Jane intimated that she would welcome a draft of a purchase agreement. It took another year to iron out the wrinkles and find the right language, but we made it. Jane signed. From there, things started to happen fast.

Waiting ten years is not something we would have chosen, but the experience taught us some important lessons. For instance: “No” means “maybe,” and “someday” often becomes “now.”

Once we had the rights, Lisa reached out to two directors she knew quite well, and whose work she had produced previously, but both had scheduling conflicts. That’s when we went out to James Marsh. He seemed like a potentially perfect fit, as he had tackled a complicated true-life character in Man on Wire, and in everything he does, he focuses on the truth of a story. He anchors each scene with a realness; a true sense of veracity and we knew that was essential to this tale.

“Long before we had even secured the rights, Anthony was so captivated by Stephen and Jane’s story that he wrote a screenplay adaptation.”

In addition to his talent and directorial sensibility, James meant a lot to investors. There was just a general excitement around him, a feeling that he was about to move beyond documentaries, where he was already an established force, and break into dramatic features. He responded quickly to the material, particularly the approach of the script, which took him by surprise. He had not anticipated a love story, and such an unusual one at that. He came on board immediately.

All of the time spent waiting for Jane to grant us the rights paid huge dividends when it came to honing the script, because the financiers felt the same way when they read it. We reached out to a few investors, and the response was overwhelmingly positive, so Lisa emailed the script to Eric Fellner at Working Title in London. She had produced a television film for him and his partner Tim Bevan and knew they would be the best fit for this movie.

Eric replied in eleven hours and said, memorably, “Everyone here has read it. Why don’t you come in for a meeting?” The pace only accelerated from there. Eric told us at the time, “Our job is to make it easy for you.” And they most certainly did. We almost felt pampered. No, screw that — we did feel pampered.

There are few places where filmmakers can go and get both the right amount of money, as well as the right amount of creative support, and Working Title is definitely one of them. From script notes, to casting, to production, and all the way to the final mix, they supported this movie. And Universal and Focus Features have been providing the ultimate push with the right kind of theatrical release for a picture like this.

Of course, the movie wouldn’t work without the right cast. Finding the right actor to portray Stephen Hawking was daunting because we knew if we missed by even a few degrees, the movie wouldn’t sail. For a few years, we had had a short-list for who could play Stephen, and while the odd name dropped off and a new one was added, the word “short” is apposite. Quite simply, not many actors could have done it.

We needed someone with the requisite chameleon gifts, looked passably like Stephen and was English. Eddie Redmayne ticked all the boxes, plus he knew that exact world, because he had studied at Cambridge University, as Stephen had. And when James spoke with the small number of contenders, Eddie’s passion for the role filled the room, head and shoulders above the others. We went with the passion. In fact, it suddenly seemed that there was no other choice in the world.

“The magical moment for all of us was when [Hawking] saw the finished film, and the lights came up and he was simply crying. That moment made the whole journey worthwhile.”

If finding our Stephen was a daunting task, the act of actually playing him and pulling it off with incredible compelling truthfulness was exponentially so, and to watch Eddie transform his body, his face, his movements and his emotions through a twenty-five-year span of this man’s life was one of the most remarkable acting achievements I can ever hope to be part of and witness.

Given the love-story focus of the story, it was equally daunting to cast the role of Jane Hawking. Now we cannot imagine anyone else in the world who could have brought the subtlety and complexity of her character forth in a more layered and beautiful way than Felicity Jones did.

The shoot was full of memorable moments, but neither of us will forget the day the real Stephen and Jane visited the set. We were staging their first date — a recreation of the 1963 May Ball for Cambridge undergraduates. We had 300 extras in black tie and gowns, two bands, a carnival, and a few thousand quid worth of fireworks ready to erupt in the cold autumn night.

Jane had arrived with her husband, Jonathan Hellyer-Jones, who is also a major part of the film. Then the Professor arrived. A staffer was dispatched to halt the Professor beyond the edge of frame. This was narrowly accomplished. James called “Action!” and the music struck up, 150 couples began to waltz, gloved waiters served champagne from silver trays and the bands played soft jazz until the sky suddenly filled with supernovae. We were told later that the Professor smiled. Perhaps in that moment he was young again; a nervous youth on his first date with the woman with whom he’d share half a life. Had Anthony been at his ear he might have whispered: “Professor? That’s Hollywood.”

That same day, Tim Hawking, the youngest of the Hawking’s three children, was there as well. At one point, Lisa approached him as he was watching Eddie and Felicity as they walked with champagne in hand — a young couple falling in love. He looked at her with a real moment of reflection, caught in the moment as though it were a look back into a time he could not otherwise have access to, and simply said, “I never knew my dad as an able-bodied man.”

“Waiting ten years is not something we would have chosen, but the experience taught us some important lessons. For instance: ‘No’ means ‘maybe,’ and ‘someday’ often becomes ‘now.'”

In making the film, we were endlessly humbled by the road that Jane and Stephen actually walked. And we were moved by how generous they were in sharing both their lives and all the messy details with us to make this story possible. Jane was particularly involved, and made herself available and open in the early script development. Stephen then became involved in prep and production, and he offered up his actual thesis and medals and awards for us to use in key scenes. But the magical moment for all of us was when Stephen saw the finished film, and the lights came up, and he was simply crying. That moment made the whole journey worthwhile.

What can you say about Stephen Hawking? There are meetings with remarkable men, and there are remarkable meetings with remarkable men. With Professor Hawking, all meetings fall into the latter category. While he writes his question or his answer, at a rate of about three or four words a minute, the visitor is gifted with many long, unwanted minutes, which the normal rules of civility oblige you to fill in with your own gabble.

Anthony had prepared a decent-sized speech in anticipation of his reaction to the script, because the Professor had requested a copy be sent to him prior to meeting us, but his speech had long-since concluded by the time Professor Hawking had written barely the first few words of his first message. Anthony turned in desperation to James Marsh, a normally loquacious fellow who, under the pressure of the circumstances, could manage only the odd line or two. We so deeply craved his blessing, and this was by no means a given. The script was unflinching and, remember, it was inspired by his ex-wife’s autobiography!

And then he spoke. That iconic computer-voice boomed forth.

“The ending of your film…is…too…” It felt like a lifetime waiting for that climactic word: “…sweet.”

Sweet? Anthony looked at James. Did he just say “Sweet”? The relief! Especially as he could just as easily have told us: “Lawyer up, dude.”

In reply, Anthony gave him the only answer he could conjure: “That’s Hollywood.”