When King George VI assumed the British throne in 1936, he was faced with the challenge of uniting a country on the brink of war and mired in a crippling depression. The prospect would be daunting for any world leader, but it was complicated by a Royal secret: the king — christened Albert, and affectionately known to friends and family as “Bertie” — had a pronounced stutter. And with radio broadcasts becoming an essential way to communicate with the people of the United Kingdom, Bertie’s impediment might be unveiled in a most public way.While Bertie eventually conquered his stutter through an unlikely friendship with Lionel Logue, an unorthodox Australian speech therapist, the production team that told his story in The King’s Speech had its own challenges. From a difficult financing process to shooting in a city that was a bit too clean to finding just the right stutter for Bertie, giving voice to the king wasn’t as easy as it seemed.

When King George VI assumed the British throne in 1936, he was faced with the challenge of uniting a country on the brink of war and mired in a crippling depression. The prospect would be daunting for any world leader, but it was complicated by a Royal secret: the king — christened Albert, and affectionately known to friends and family as “Bertie” — had a pronounced stutter. And with radio broadcasts becoming an essential way to communicate with the people of the United Kingdom, Bertie’s impediment might be unveiled in a most public way.While Bertie eventually conquered his stutter through an unlikely friendship with Lionel Logue, an unorthodox Australian speech therapist, the production team that told his story in The King’s Speech had its own challenges. From a difficult financing process to shooting in a city that was a bit too clean to finding just the right stutter for Bertie, giving voice to the king wasn’t as easy as it seemed.

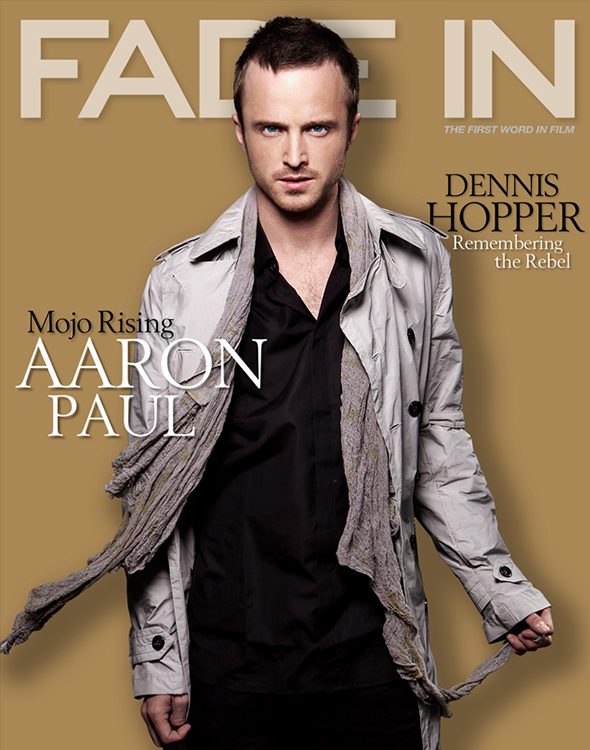

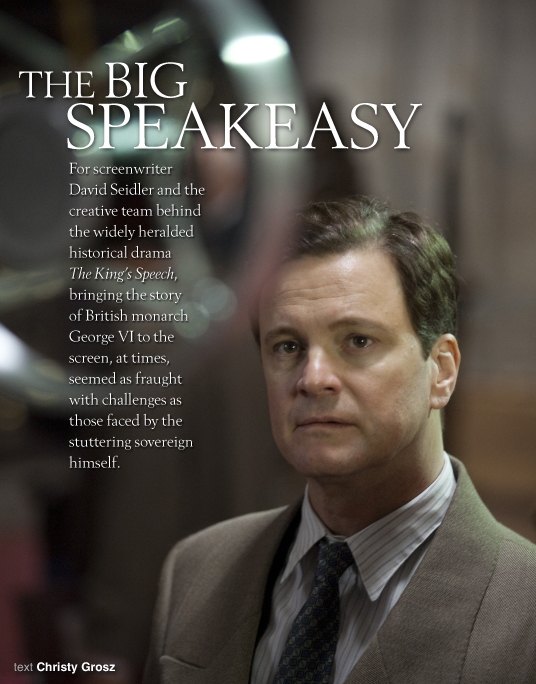

Long before Tom Hooper signed on to direct and Colin Firth and Geoffrey Rush agreed to star, the screenplay for The King’s Speech had been simmering in the mind of screenwriter David Seidler, who used to suffer from a stutter of his own. Though he didn’t connect the dots until adulthood, Seidler can trace the origins of his stutter — and his subsequent affection for the king — to his tumultuous childhood in England. Seidler was born in London between the two World Wars, but shortly after World War II started, he and his family moved out of the city to the relative safety of England’s southern coast to escape Hitler’s bombs.

“It was probably a rather good thing because an incendiary bomb came through the roof of my [London] nursery a week later,” says Seidler, who was barely a toddler at the time.

His earliest memory is of watching his father and uncle paint a sandbox at their new home and hearing loud booming noises in the distance. He didn’t know it at the time, but he was hearing the guns of Dunkirk, in northern France, site of a large-scale military evacuation in 1940.

“The next thing I knew, we’re on a boat going to this strange place, and my second memory is the Statue of Liberty,” he says. “That’s when I started to stutter.”

In America, Seidler’s father followed news of the war on the radio, and when young David was old enough, father and son would listen to King George VI’s speeches.

“My parents said, ‘Now, you know, he was a stutterer, just as bad as you, if not worse. And listen to him now,’” Seidler recounts. “I could tell that he still stuttered a bit, but not badly, and he was able to give these wonderfully moving addresses.”

Seidler eventually got over his stutter during adolescence, but he remained an admirer of the king. So much so that, as an undergraduate at Cornell University, he seriously considered writing something about Bertie.

“But final exams and girlfriends interceded and nothing got done,” he says with a laugh.

Decades went by, and Seidler moved to Hollywood, where he scored his first writing job when Francis Ford Coppola hired him to pen the script for Tucker: The Man and His Dream.

“I was forty years old, but I was still naïve enough to think that two things would happen: This would change my life instantly and that I could do anything in Hollywood that I wanted to do,” Seidler says.

Neither happened, but the experience spurred him to start researching the king’s life. He also made a fortuitous call to a friend in London, who used the local telephone book to find Logue’s surviving son, Valentine, who was a retired brain surgeon. Seidler wrote to the man, who agreed to cooperate and offered up his father’s diaries for research purposes. Valentine, however, had one caveat: The film had to have the blessing of the then-80ish Queen Mother, Bertie’s wife Elizabeth, played in the film by Helena Bonham Carter.

“I wrote to the Queen Mum, and I got a reply saying, ‘Thank you, Mr. Seidler, but please, not during my lifetime. The memory of these events is still too painful,’” he recalls. “When the Queen Mum says wait, you wait.”

Unfortunately, Seidler had to wait for nearly three decades until the Queen Mother passed away in 2002. By this time, the trail had gone cold: Valentine had long since died, and Seidler didn’t know the fate of Logue’s diaries.

“It came at a time when the Lehman Brothers had crashed. The idea of a historical drama was a bad word in the U.K. and U.S. That’s why I really admire Harvey [Weinstein’s] ability to spot this film early on. He believed in the material like we did.”

– Iain Canning, Producer

Seidler was also dealing with some issues of his own. In 2004, he was diagnosed with bladder cancer, which hit him extremely hard. Yet three or four tear-filled days later, he decided to revisit Bertie’s story.

“I had to get my mind off of [the cancer] and the best way was to plunge myself into creative work,” he says, adding that he’s now in full remission.

In 2005, he showed the completed screenplay to his then-wife and writing partner, Jacqueline Feather, who suggested that he write the story of Lionel and Bertie as a stage play in order to focus on drawing the details of the key relationships. The move from screen to stage seemed to finally give the project the momentum it needed.

His actor friends raved when they read the story in play form, but Seidler wanted the opinion of another writer, so he sent it to his college roommate’s nephew, Tom Minter, a playwright who was working in London at the time. Minter passed it on to London-based producer Joan Lane, who gave it to Bedlam Productions. Bedlam optioned the movie rights immediately and eventually brought SeeSaw Films’ Iain Canning and Emile Sherman on board as producers in March 2008.

“I read it through in one sitting,” Hooper says, though he admits that it took him a couple of months to get to it. “I rang my mum up and said, ‘You’re absolutely right. It’s my next film.'”

Rush and Hooper came to the same conclusion independent of each other: The King’s Speech was a film both wanted to be a part of.

“Hooper read it and said if we were two weeks away from filming, I would be sleeping well,” Seidler says.

“Well, fifty drafts later, I did remind him of that.”

Hooper and Rush worked with Seidler while he was polishing the screenplay and working out the kinks in the story, from historical details to chronological issues.

“At the end of the [original] script, he was cured,” says Hooper. “He could speak like Laurence Olivier without a stammer. If he’s cured, then there’s no possibility of failure and no real drama.”But even with a nearly polished script and talent attached, Canning says that organizing the financing wasn’t easy. SeeSaw has a first-look deal with U.K. distributor Momentum Pictures, which provided overhead to develop the script. SeeSaw’s sister company Transmission Films signed on to distribute in Australia. And Harvey Weinstein, co-chair of the Weinstein Company, was chomping at the bit for North American rights.

“It came at a time when the Lehman Brothers had crashed,” Canning explains. “The idea of a drama, especially the idea of a historical drama, was starting to be a bad word in the U.K. and in the U.S. That’s why I really admire Harvey’s ability to spot this film early on. He believed in the material like we did.”

Once the deal with Weinstein closed, the rest of the pieces started falling into place quickly for the $13 million-$15 million film. Seidler’s script was close to being locked, and Hooper was thrilled when Firth signed on to play Bertie.

“From my research about King George VI, I felt he was a gentle man with great humility,” Hooper says. “Colin doesn’t have a malign bone in his body, and he has tremendous humility. He’s a very gentle man, an intelligent man. Spiritually, there was such a strong connection between the men.

”Because Hooper and Firth had such affection for the king, they wanted to strike a precise tone for how and when Bertie would stammer.

“There’s a pitfall that it could be funny. There’s a pitfall that it could be too uncomfortable to watch.

There’s a pitfall that it’s so slow that by the end of 100 minutes, you’ve only seen three scenes,” Hooper explains, adding. “The thing I’m most proud of is the rhythm of the stammer, when it should be pronounced and when it should be set back.”

“The stammer looks like it’s coming from his brain,” Canning adds. “You see the physicality. He’s desperate to show how his mind is working in the silences.”

The physicality of the stutter gave Firth headaches and left him exhausted during the production. It also lingered long after wrap.

“It does get into your system,” Firth admits. “By the way, Derek Jacobi — who, if you’re English and of my generation, is probably one of the most famous [onscreen] stutterers for I, Claudius — reassured me that it goes away. It happened to him, too. He found himself stuttering for a few weeks after the end of the work.”

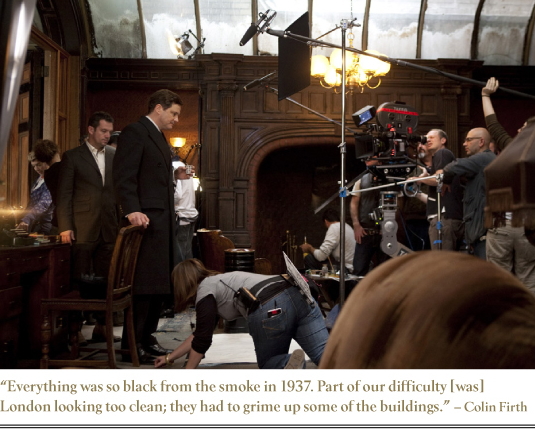

In addition to researching the king himself by watching old clips and reading histories, Hooper and his production team sought locations that to re-create 1930s London, as well as stand-ins for royal buildings like Buckingham Palace.

Production designer Eve Stewart, who has worked with Hooper on several other film and TV projects, says London “was a dismal old place” between the wars, and wanted the film to reflect that.

– David Seidler, Screenwriter

“People were living hand to mouth, and all these lovely, grand old buildings were just crumbling,” Stewart says.

The dirt and dense smog of London started disappearing in the 1960s, so many of the exterior locations had to be modified in postproduction.

“Everything was so black from the smoke in 1937,” Firth says. “Part of our difficulty [was] London looking too clean; they had to grime up some of the buildings.”

In addition to using period furniture to dress all of the locations, Stewart says budget constraints made re-creating the BBC broadcasting room particularly challenging.

“It’s always easier to find a cell phone than a great big radio dial,” she says with a laugh, adding that she tried to use antiques wherever possible. “It’s really important that the actors have real artifacts from that period to ground them.”

As prep on the film started ramping up, one final — and critical — piece of research finally arrived: Logue’s diaries and medical notes. The film’s production department had found an email address for Logue’s grandson, Mark, so Canning dropped him a line to tell him about the movie and ask him for a meeting. Mark agreed, and brought with him some of his grandfather’s notes, which had been gathering dust in the attic.

“So I went through a couple of pieces of general paper, and I got to a piece of paper which had the Buckingham Palace red insignia at the top, and it was the annotated version of the final speech, with all the marks,” marvels Canning. “What was so amazing with Mark is that he went through his own journey of understanding his grandfather. He’s gone through to really getting the heart of the man, finding out who he was.”

Not only was the production department able to re-create that annotated speech for the film, but Logue’s notes provided insight into both men’s personalities.

“Some of the great lines that pepper David’s fantastic screenplay are from those men themselves,” says Canning. “It was like finding the box of treasure buried in the back garden.”

For Rush and Firth, reading about each man in his own words provided the texture they were seeking for their performances.“There were letters in there from patients that Logue had treated during the First World War,” Rush says. “They were still writing to him in the ’30s thanking him for his decency and his friendship and his gentle manner.”Firth discovered that Bertie, who had been portrayed as somewhat dim-witted because of his stutter, had a charming, self-deprecating sense of humor.

“The diary gave Colin a tremendous clue as to the wit of King George VI,” says Hooper. “We would then look to David to amplify the wit of the king in other places.”

Following a three-week rehearsal period, the seven-week shoot began in London in November 2009. Though the already small budget got even tighter when an exchange-rate shift meant shaving off another $1 million, the biggest challenge during production was accommodating the schedules of three high-profile actors. Rush had to finish by Christmas to start a play in Australia; Firth was jetting to the U.S. to promote A Single Man for awards season; and Carter was only available on weekends because of her role in Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows.

“She was the only person that Tom and I wanted to play that part. We were the divorced father in a sense, [because] we had her [only] on the weekends,” Canning quips.

Although Firth and Rush had spent much of their rehearsal time working on the six therapy sessions that spark their characters’ friendship, Rush says he was still concerned about how the long scenes would play on-screen.

“In the back of my mind was that some of these scenes are eleven pages long. But once we started to really dig into them and find out what was happening, they became the center of the story,” Rush says. “After a few days, the editor had already done a rough assembly. The stillness and the awkwardness of the first encounter [worked], so we just trusted that and moved on.”

Yet as hard as Rush and Firth worked to make the therapy sessions successful, Hooper discovered that shooting a moving scene between the king and queen was far more challenging. In it, the king breaks down in his wife’s arms, tearful over the mounting pressure he’s facing, and Hooper says Firth went into the scene conflicted over how much emotion to show.

“He’s a repressed Englishman. He’d say, ‘But if I cry, is that too emotional?’ It was quite a lot to get him to the point where he would allow himself to be vulnerable. Colin is so afraid of being self-pitying,” Hooper says.

Production wrapped in January 2010, shortly before Firth earned an Oscar nomination for A Single Man. Following a routine postproduction period, spent mostly removing modern buildings from the film’s handful of exterior shots, French composer Alexandre Desplat — who has Oscar nominations for his music in The Queen, The Curious Case of Benjamin Button and Fantastic Mr. Fox — signed on to create the score.

Desplat spent a brief three weeks composing the film’s music, for which he found inspiration from the classical orchestral pieces Logue played for Bertie during their sessions.

“The most difficult thing is the balance between laughter and tears,” says Desplat. “The audience really laughs and really cries, and the music has to respect that.”

Through the chief engineer at London’s famed Abbey Road Studios, Desplat located a set of antique silver-and-gold microphones that had been created for the royal family and used them alongside a modern setup when he recorded.

“We used George VI as the center microphone, Queen Elizabeth as the left side and Queen Mary’s on the right side,” Desplat says. “George V was a bit more tricky to use, so we kept it on the desk as an homage.”

The final cut of The King’s Speech was completed Aug. 31, 2010, just days before it made its world premiere and earned the audience award at the Toronto International Film Festival.

But even though it has been a year since shooting wrapped on the film, Hooper has found that, although he doesn’t stutter, he still maintains a strong personal connection to Bertie’s plight.

On one particular night, Hooper was sitting in the audience at an awards show, waiting to give an acceptance speech for an award he was receiving because of the film. As minutes turned to hours — three hours, to be precise — the director grew increasingly nervous about what he was going to say. The irony was not lost on him.

“What’s so funny about promoting the film is that you’re constantly connecting back to public speaking,” Hooper explains. “You watch other people do a speech, and you go, ‘Oh, that was brilliant, better than mine.’ You’re not really enjoying yourself; you’re nervous about making a speech. You face those microphones, and you’re brought back to your hero’s predicament over and over again.”

But for Rush, the strong bond between therapist and monarch is what left a lasting impression.

“Even my agent said, ‘I just found myself weeping at the end,’” recalls Rush. “I said, ‘Was it the impact of the speech?’ He said, ‘No, it was the final title card that said King George VI and Lionel Logue remained friends for the rest of their lives.’”