PARTNERS IN SUBLIME

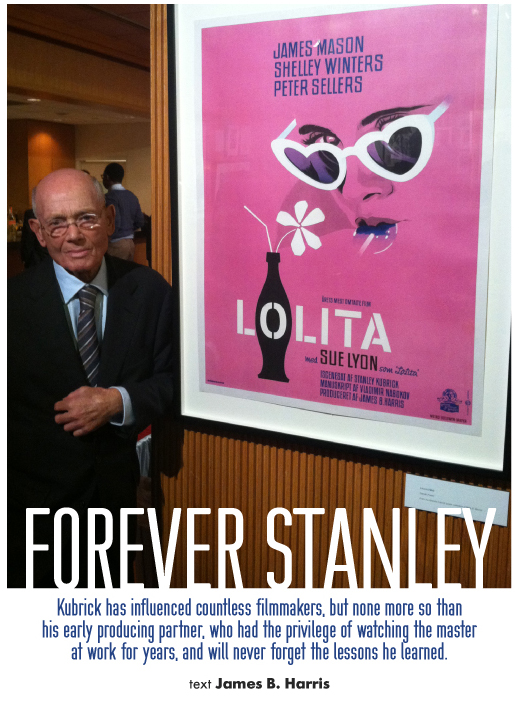

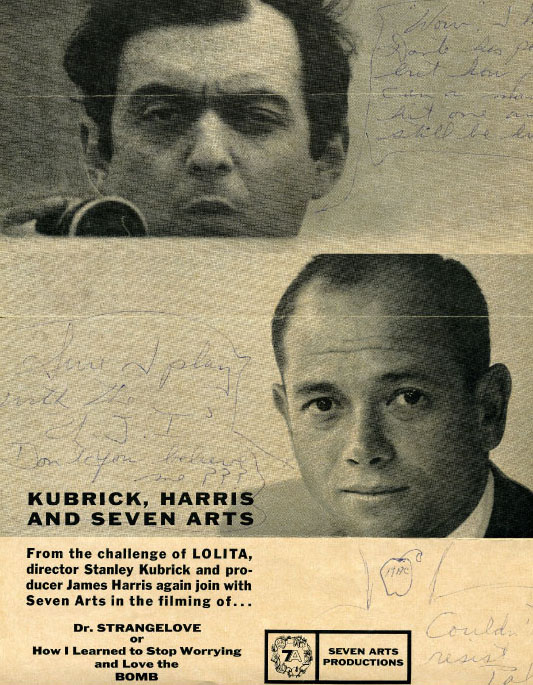

Stanley will be missed by many, but not by me. The reason is simple — he’s still with me. He’s been with me for forty-five years — since 1955, when I became his partner and closest friend — and he’ll be with me until the day I die. And after that — who knows? We’re talking spiritually, of course. In fact, our partnership only lasted for eight years and three films (The Killing, Paths of Glory and Lolita). After arranging for the financing of what was to be our fourth film, Dr. Strangelove, I chose, with Stanley’s blessings, to pursue a career of my own.I’ve been asked many times, “Why, when you and Kubrick finally gained the recognition you were seeking, did you walk away from it?” And I always answer, “Because it no longer offered the kind of recognition I was looking for.” It may have been when we first started with The Killing, but standing side by side with Stanley, watching him so expertly direct the films that followed, including Spartacus, I came to realize that the true fulfillment one looks for in filmmaking can only come from directing. Stanley always told me this; so I suppose, based on the artistic contributions I made as we went along, he felt that he should begin to prepare me to make the transition to director.

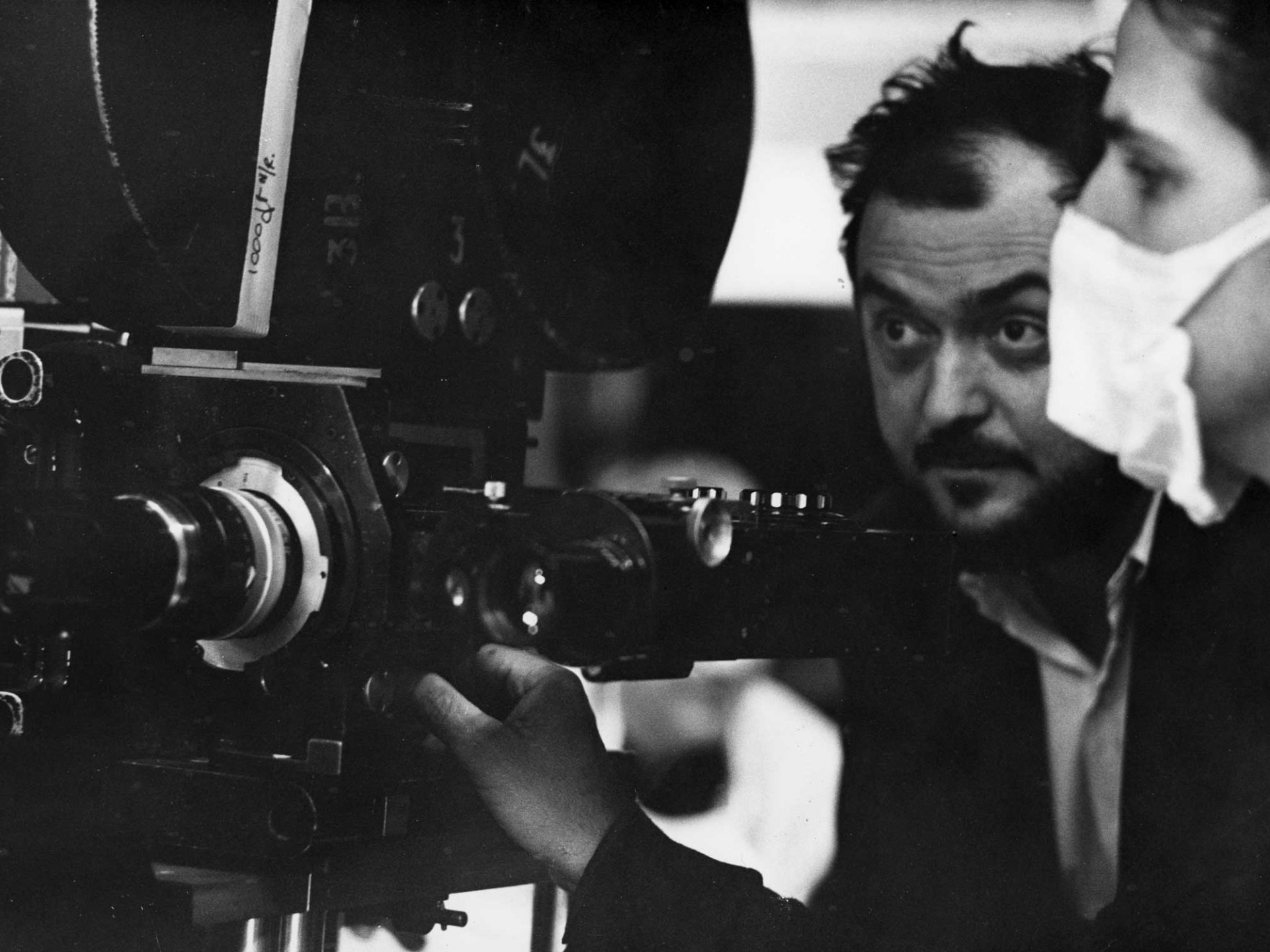

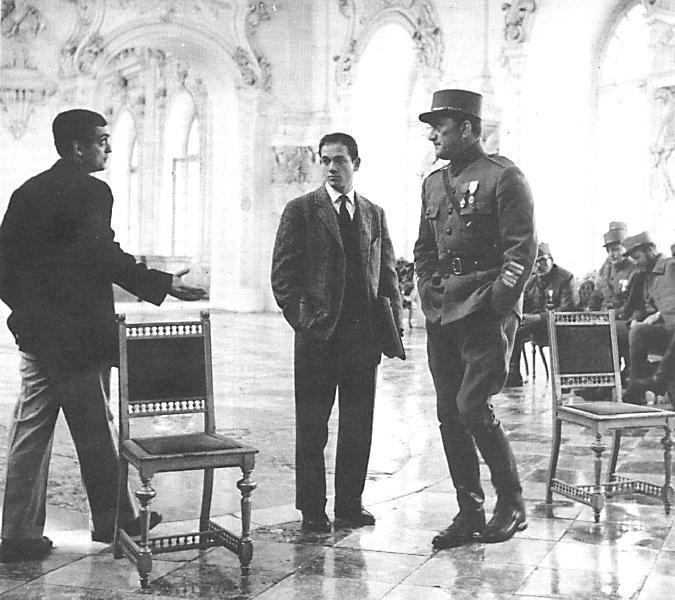

First, he familiarized me with the work of directors he admired, such as Max Ophuls, Vittorio De Sica, Federico Fellini, Akira Kurosawa, Sergei Eisenstein and others. He encouraged me to participate in the development of all our scripts, which had me exchanging ideas with the likes of Jim Thompson, Calder Willingham and Vladimir Nabokov.On the set our chairs were side by side, and he actually enjoyed explaining his every move as he directed. This included rehearsing the actors, blocking the scenes, selecting his camera setups, even which lenses he was using to get the various image sizes he wanted.

I defy anyone, even those with a limited knowledge of film, not to want to direct themselves when positioned so close to a master at work. But that wasn’t the only reason I moved in that direction (no pun intended). To a great extent, the challenge of producing was gone. I had made my point. Once we completed and delivered Lolita, Stanley was established as one of the most talented directors in the world — something I had perceived and gambled on years before. Financially, we had broken through, and money was no longer an object for either of us. I had arranged for the financing of our next film, Dr. Strangelove, so there was no guilt about leaving Stanley to fend for himself. What was there left to do? Only direct.

If ever the cliché “easier said than done” applied, it was my first attempt at directing — The Bedford Incident. Stanley was to filmmaking what great athletes are to sports. He made the difficult plays look easy. But if I hadn’t taken Stanley with me, I never would have been able to get through my first attempt at directing.

Naturally, Stanley wasn’t there physically, but he was there in spirit, looking over my shoulder, whispering in my ear, guiding me through the minefields where one false step could blow an irreparable hole in the film.

I was shooting in London and Stanley was in New York, working with Arthur C. Clarke on the screenplay for 2001. Thank God for the telephone. Sometimes it wasn’t enough to trust to memory how Stanley had solved all the same problems facing me at the time. I had to get that injection of encouragement and straight advice from the doctor. I ran up quite a trans-Atlantic phone bill, but it was worth every penny.

I had to be reminded of what was in all those books he had me read. Like Stanislavski Directs, An Actor Prepares and Freud’s Introduction to Basic Psychoanalysis. Had to be reminded that, “If a scene doesn’t play, be sure your actors know their lines, be sure they completely understand the scene. If it still doesn’t play, it can only be that the scene isn’t written properly. Best you rewrite it.”

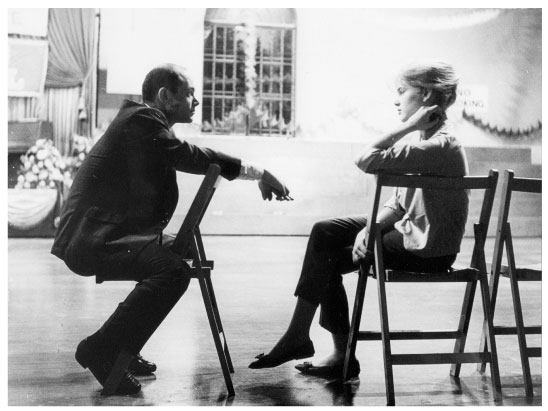

Another sound piece of advice was: “You shouldn’t let yourself be bullied by production managers and production executives, whose only concern is to stay on schedule. They’ll be pushing you to do your homework and prepare in advance all your camera setups in the form of a shot list. If you do this, and approach each day’s work with a preconceived mindset, you’ll be depriving yourself of any magic that can happen when, with an open mind, you get your actors together and work with them in staging the scene. Many times an actor’s instinct is worth listening to. This way, when you figure out how to photograph the scene you’ve just blocked, you will be letting the camera accommodate the actors — not the reverse, which, generally speaking, is mechanical filmmaking — a blessing to the hack who shoots the schedule and the budget, not the film.”

I suppose (the above notwithstanding) the most important essentials of good filmmaking I learned from Stanley dealt with the script and the casting. The adage “You can’t make good mayonnaise from rotten eggs” was never more true than when applied to the hopeless task of turning a flawed script into a superior film. It can’t be done. Don’t let your ego mislead you. Fancy camera moves and cinematic tricks won’t do it. The play is still the thing, and Stanley made sure I didn’t forget it.

He also drilled into my head that casting is the single most important element of directing. As he put it, “You live or die by your choice of actors. They can be brilliant and bring to your film a dimension beyond your highest expectations. But they can also be incompetent, irresponsible, subject to moods, insecure, and the bearer of unlimited personal problems, which can easily affect the rest of the cast and turn the best-intended film into a shambles. Remember, unless you’re fortunate enough to have the financial wherewithal to replace a bad actor — which means reshooting all the scenes where he or she appeared — you’re stuck with them for the rest of the schedule.”

With this in mind, I assembled an absolutely perfect cast for my first film. How could anyone do better than having Richard Widmark, Sidney Poitier (that year’s winner of the Academy Award for his performance in Lilies of the Field), Martin Balsam, Eric Portman, James MacArthur, Wally Cox and even Donald Sutherland in a small role — all there to make me look good as a director? Stanley was right: “Casting isn’t ‘important’ — it’s everything.”

When I completed The Bedford Incident, a series of screenings were scheduled in London — not only for the executives at Columbia, who financed the film, but for close friends and opinion makers who could start the “word of mouth,” if the word was good. It was. Then came Los Angeles. The same thing. The word was good. This, of course, was most gratifying, but as far as I was concerned, until I got to New York and screened the picture for Stanley, the jury was still out.

That night finally came. And for the first time, I knew what fulfillment was really about. Stanley made it clear in no uncertain terms that, in his opinion, I was well on my way to being a director he would be proud of. Now we could both feel comfortable that working on our own, independent of the original partnership, would not be harmful to either of us.

But that didn’t mean I intended to discontinue my spiritual connection with Stanley. On the contrary, he has been with me through all my films thus far, and I’m certain he’ll be there with me on all the ones in the future. As always, our chairs will be side by side on the set, and I’ll be hearing that whisper filling my ear with those “Kubrickisms” that give me the confidence and strength to do what seems to me to be the most difficult job in the world.

Maybe now you understand why, after has Stanley passed on, I don’t miss him. How could I? As I said, he’s been with me for forty-five years, and he’ll be with me until the day I die. And after that — who knows? Maybe we’ll wind up in the same place. Maybe we’ll start up the partnership all over again. And maybe this time, I’ll stick around a little longer.