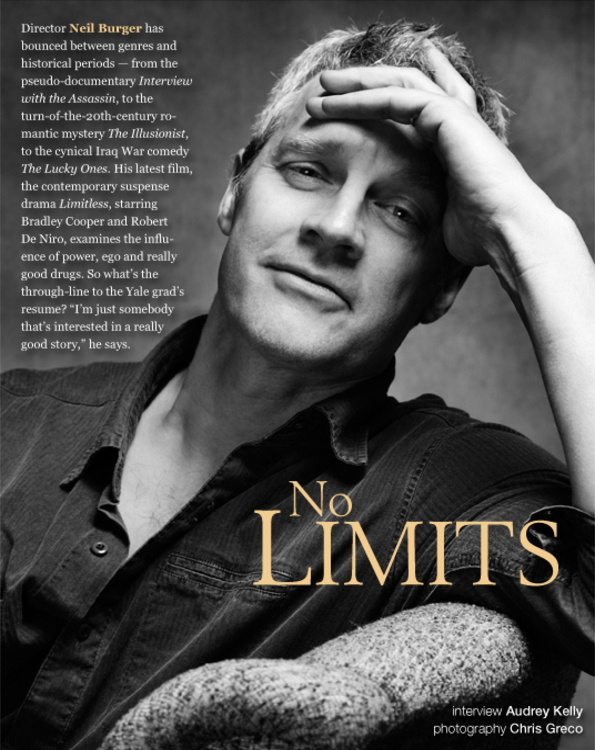

What was your initial reaction when you got the script for Limitless [a.k.a. Dark Fields] from Leslie Dixon, a writer who’s primarily known for broad comedies? I just read the script and I liked it. I like the crazy nature of it, and I liked that it was a wild story but was told in a very true way about the ambitious people in New York, and about the idea of power in New York City. So that appealed to me.

What was your initial reaction when you got the script for Limitless [a.k.a. Dark Fields] from Leslie Dixon, a writer who’s primarily known for broad comedies? I just read the script and I liked it. I like the crazy nature of it, and I liked that it was a wild story but was told in a very true way about the ambitious people in New York, and about the idea of power in New York City. So that appealed to me.

With all the pharmaceutical companies out there feeding off the public, one of them must have already tried something like the drug in the film? There are people developing drugs like this out there, and there are already drugs that are being repurposed through Adderall or Provigil that are being used by college students and other people to let them focus and inform better. So this drug is a fictional drug, and it’s like steroids for the mind, with all the benefits and all the negative things that go along with that, and more. Ultimately, the movie is about a guy who is taking a smart drug — who has come to the end of his rope, and what he’s doing with his life, and he’s just failing big-time. Suddenly, he gets the chance to turn that around and become the best version of himself, and to really succeed and to be able to do — not in a superhero way, but to be able to do everything that he feels he should be able to be do. He’s fearless in social situations, and he’s able to just remember everything he’s ever heard and seen and draw conclusions on it and act quickly. So he is able to work in the stock market and meet women and do all sorts of things that he was always having trouble with.

Which is what everyone wants. Everybody wants to be the most successful version of themselves, and there’s a lot of people who want to be different people as well. But it’s not an unreasonable thing to think that you could be the perfect version of yourself, and this guy played by Bradley Cooper gets that opportunity.

Wasn’t there a delay in production back in ’08? I read [the script] in the fall of ’07, actually. And, yeah, it started out in one direction and then changed, but then nothing ever happens quickly in the film business. Then we got Bradley Cooper involved in October of ’09, and then we were off and running.

“The one thing that I’ve learned is that there has to be a reason that people want to see your movie. You can be going down the road and working on a great story, but if it has no place – if it’s not going to be seen you have to be ready for that.”

So were there any script changes when Bradley Cooper replaced Shia [LaBeouf]? As you know, Shia was involved in it and then dropped out of it at the end of ’08. So no, the original script is what we’re doing now. When Shia was involved, we were going to make changes because he was so much younger. He didn’t really fit the character, even though he’s a great guy, and I like him a lot. But, really, the script is written for a character that is exactly Bradley Cooper’s age. So, yeah, things worked out.

Did Robert De Niro intimidate? Well, going into it as a director, you’re thinking, “All right, I’m going to tell Bob De Niro where to stand and how to say his lines. I can do that.” So that’s a little nerve-wracking. But I had known him a little bit before. We had met after The Illusionist, which he had liked, and briefly talked about doing something. So it wasn’t completely a cold meeting, and then we met a number of times in the run-up in the preparation of the movie. So by the time he got on set, I felt pretty comfortable with him. And he is truly the easiest-going guy on set; at least for me, he was. He was a real joy to work with. So that was a huge relief, more than anything else, and then a pleasure to see him act and just to turn on what he can do and really just deliver a powerful performance.

The Limitless screening we saw back in November was perfection. Now we hear you changed the ending? Why? There was one thing with the ending that we never quite finished because we couldn’t get all the actors together [at the same time], so it took us until the end of January just to shoot that scene, which makes the final dash to the end all the more crazy. So most of the [postproduction] has been on hold until we finished that.

So did the ending change? Not really.

No test screening surveys — none of that? No. We had a preview [with] scored testing. That’s just the way it is these days. And it tested really well.

Why the title change to Limitless from Dark Fields? The movie is based on a book called The Dark Fields, and “the dark fields” is from a quote from The Great Gatsby. It’s an obscure quote of Nick Carraway thinking back about where he’s come from, and sort of the dark fields in America laid out behind him. It’s beautiful, but it’s obscure. And we found that people would get to the end of the movie and they would be like “Why is it called Dark Fields?” Even though I liked the title, nobody could ever quite explain, in a compelling manner, why that title should be the title. So they changed it.

“They”? Well, the financiers changed it. I liked the title Dark Fields; but Limitless, I suppose, is more evocative, and I’ve talked to a lot of people — friends, even, whom I thought wouldn’t like it. They’re like, “Oh, yeah, much better.” So at a certain point, you’re like, “Well, maybe it’s not a bad idea,” and you go with it.

Were you upset at first? I wasn’t upset; it was a long, drawn-out process of trying to figure out a new title, and I was proposing titles, too. So by the time it happened, it was inevitable.

Universal is listed as one of the producers. I don’t think so anymore. Here’s what happened. The movie was completely at Universal Pictures. Then, when Shia dropped out, Relativity came in to co-finance it — or actually to produce it, and Universal was going to distribute it. Then Relativity bought Overture, which has really become a full-fledged studio. They are a studio — there’s no question about it. And they were happy with it, so they wanted to take total control of it and distribute it themselves. So in a way, it is not the first film they’re distributing. But I feel like it’s the first [one] that they really feel complete ownership of, and a real fondness and excitement about, which is great.

They’re right to feel that. You did an amazing job with a complex script – especially with all the hurdles that were thrown your way. Well, thank you. The hardest thing was [that] it is this freewheeling, crazy movie. [Bradley Cooper’s character is] all over the place. Sometimes he’s all over the place because he’s skipping and he’s losing his own sense of time; but also he’s just a guy on the move. And he goes from being a failure with no money, and sort of this ragged character, to being this very polished, impressive individual. So he just inhabits all parts of Eddie. So there were a zillion locations. Like any movie these days, they all have to be done for a price, and everybody’s money is much tighter. Well, there’s plenty of money, but to do what we were trying to do, it was tight and we didn’t have enough time to really get all those locations and get all those shots and all those scenes. There’s a lot of small scenes that are in completely different locations, and to put that all together it was a crazy puzzle that had to be fitted together. So with the time constraints and money constraints it was no joke to get it done, and to get it done with some polish that I believed in visually.

How did you decide how to shoot the dream aspect of the film? I was trying to find a way to do something that really made us feel what it would be like to be going through that experience. And somebody who’s really smart, how do you show how their mind works? You could flash a lot of charts and things like that up there, and you’d just assume, “Oh, well, there’s all these numbers in their head, and somehow they’re able to process it.”

My feeling was, “Well, how do you actually show that they’re able to process it? Rather than just being a mash of data, how do you show how they work their way through it…and to do it in a way that we hadn’t quite seen before? Which didn’t mean they were reinventing the wheel on visual effects, but really, in a way, combining sometimes very simple things and simple camera moves and simple visual ideas to be expressive of how his mind works.

Then, when he’s time-skipping, when he’s losing it, it was the same thing: What does it feel like to black out, to really black out? There’s so much jump-cutting in films these days— everything’s cut so fast, and we can all go with the fact that here we are, sitting in these chairs, and the next thing, boom, we’re in a car, and nobody questions, “Well, how did they get to the car?” It’s all assumed that, “Oh, they went out and they got in the car, and now we’ve jumped ahead in time, and that’s just the way narrative works these days.” So then how do you do something when somebody’s blacking out? How do you really show that?

So I was just trying to come up with what he felt like when he was blacking out, that one moment he’s lifting up a glass, and then, once he brings it up, he realizes he’s somewhere else, and to give that sort of vertigo and that disorientation. So it was really a matter of thinking about it myself and trying to figure out visual correlations to those feelings.

Did you end up watching certain films to get ideas? Yeah, yeah, you watch all sorts of things – new films and old films, and you pick little pieces and you hopefully find a way to recombine your influences in a way that’s somehow new. That’s the trick.I always say the bullet time in The Matrix, that would have been perfect for this movie; but it’s already been done, and now it’s done everywhere. The local TV news is doing things like that for its little advertisements.

Really? Well, they’re speeding up and ramping the film and things like that. I didn’t want to have anything to do with that. Not because it’s not great, but it’s just done so often, it doesn’t mean anything anymore. I wanted to find something that had a different feel.

How did the parody ad for the film and having people call 1-855-Clear-Pill come about? It’s really funny. It’s worth checking out. We came up with this idea of making a fake infomercial for the drug. The movie is an intense thriller, but the movie is also funny; it has a real dark sense of humor to it. So we thought that we would play with that and came up with an idea of Bradley playing Bradley selling, hawking the drug. It looks like one of those infomercials that comes on at two o’clock in the morning. So it’s funny and fun, with ideas like side effects: blackouts, homicidal tendencies, suicidal tendencies, possible death, among other things.

“There’re a lot of small scenes that are in completely different locations [in Limitless], and to put that all together it was a crazy puzzle. So with the time constraints and money constraints it was no joke to get it done, and to get it done with some polish that I believed in visually.”

You made the quantum leap from making a film for less than a million dollars, [Interview with the Assassin] to being given $16 million for your subsequent film, [The Illusionist]. What advice would you give filmmakers looking to make the same jump? In my case, I had actually directed eight years of commercials, so I had handled some large crews and big budgets before. So that part, that escalation, felt fine. Obviously there’s a greater responsibility when you’re making a bigger movie. The stakes are higher. Any time you make a movie, you want it to be successful, and the thought that it’s like, “Oh, well, that one didn’t work out, because…” — it’s not possible. You spend a year, or two years, or three years putting it together — or more — and the thought of it not being successful is just devastating, and so depressing.

So, really, the stakes are high on all of them. But you’re right, when there’s more money, there’s obviously more voices involved. You have to suddenly become a diplomat in a way, and you are the author of the piece and want to have what you want and need. But you can be so specific and so entrenched that you end up sinking your own ship, or cutting your nose off to spite your face. There’s a certain amount of horse-trading that goes on, and it’s just a certain amount of balancing what’s the most important thing, the most important thing to get this shot no matter what, and then potentially sacrifice, for example, losing the next day’s locations.

That’s really the hard thing to learn: how to never walk away until you’ve gotten it on film. How far do you go and do that to the point where you maybe jeopardize everything else down the road? They can be terrifying choices.The real difference is you’re dealing with bigger actors. Those actors are operating on a different level. They’ve got other commitments; you fit your schedule in between them. Those guys go from one movie to the next, and they drop into situations that are potentially really uncomfortable for them, and they have to know how to navigate their way through them. So they are really strong, independent operators. So you need to maintain control over what the movie needs to be, even as you are wanting them to give their best performance, which involves keeping them happy without jeopardizing your own vision for the movie.

What would you say has been the most important thing you’ve learned about the film business? [Laughs] Well, the one thing that I’ve learned is that there has to be a reason that people want to see your movie. You can be going down the road and working on a great story, but if it has no place — if it’s not going to be seen — you have to be ready for that. I had a project with some actors. It was a great, great story, but for some reason, it couldn’t get any traction. It was like, “Why does that story have to be made at that time?”

The same thing with The Illusionist. It was like, “Well, why do we need to see a story about a 19th century magician?” We did and we didn’t; but it captured some people’s imagination, at the time.

I don’t know. It’s a very tricky alchemy to figure out what one needs to make at any one time. You have stories that you want to tell. What is the one that you’re really going to push with? Because if you push with that other one, it’s just never going to get either money or distribution or somehow be seen in the world, and there’s all these layers. It’s a very long road, and to think that your movie is going to languish somewhere — it’s just depressing.

Also, you only have so much time in your life to make X amount of films. That’s right. Then, on the other hand, you want to do movies that are meaningful, and of course those are the ones that are the most difficult to get made, and the ones that are most important to you, and the ones that should be made, and the ones that’ll really have an impact in society. So then, really, the trick is, how do you get those movies made and out there? What are the elements that you need to have as a filmmaker, and the people you need to bring into it? It’s sort of a never-ending struggle to try to make something interesting and good.

That has to affect your decision process when choosing your next film. Of course, yes, it does. You want to make interesting movies, and you want to see them get made. What you learn between making Interview with the Assassin and The Illusionist is, with a bigger sized movie you have more money but you also have incredible pressure to compromise, to round the corners, to take the edge off, to take the strange yet interesting tangents out. They all sort of start feeling like they’re the same movie. That’s the hard thing. You’re trying to maintain your movie, and what’s interesting about your movie, amidst people who have power over you because they hold the purse strings, and who inevitably want to soften certain things — not always, but often. And then the crazy thing is, sometimes they’re not wrong about certain things, but that’s the real struggle.

Your films thus far have not been overtly commercial. I’m trying to walk that fine line and trying to get them out there. They’re obviously meaningful to me. The four movies I’ve made were personal to me, even though they had some commercial aspects.

What is the status the New York-based terrorist pitch you sold four years ago? It seems to be languishing. The film industry is very bizarre these days. Studios either want to make smaller comedies — they don’t cost much, but potentially have a big upside — or they want to make big spectacles. This is really a great midsized crime movie that has a dark sense of humor to it, and it’s hard to get the studio to get behind it and say, “Yes, we want to make this.” It costs a little bit more than what they might want to make it for, or what they see the potential upside being. So it’s sitting there. It’s a good script, actually.

Maybe when Limitless comes out you’ll have another chance to get it made. Yeah.

What about Bride of Frankenstein? It sounds like a commercial turn for you. Well, Bride of Frankenstein was something where Universal came to me. They had been trying to reinvent that for a while, and tried it a couple of different ways. They had pretty much given up, but then they

thought they’d try one more time. They asked me what I would do, how would I do it, how would I update it? And I happened to spin in the one telephone conversation, “This is how.” [Laughs] I came up with this idea on how to do it and they really liked it.

You’re also attached to Rats of NIMH, a family film. I’ve got two not-as-young-children as they were when I started working on it, but they’d always been asking me, “Why don’t you do a movie that we can see?” A couple of my movies have been R rated. Even The Illusionist, they had to sit in the theatre and put their sweatshirt over their face at times. So they were like, “Do something for us.” So again, in that case, Paramount had come to me and said, “Look, we’ve got this book and it may not be your thing, but is it your thing?” And I said, “It’s not my thing, I’m not interested in that at all.” Then I read it, and I was like, “Oh, well, this could be very, very cool.” It was also a chance to do something that is completely photo-real CGI, just completely creating a world that looks absolutely real, but just digitally. I was interested in that challenge. It’s a sweet story, and my kids probably will have no interest in it by the time it gets made!

So now you have a family film, a commercial horror film — are there any other genres you’d like to tackle? I like political stories. There are things that I’m looking for, but I am interested in all sorts of different genres. I have a few projects that aren’t necessarily something that helps me. I have an Old West project that I’m interested in, and I have something that takes place in space. It’s like, “Which one is it, what movie are you?”

I’m somebody that’s interested in a really good story. All the stories seem to have something to do with people who are out of power somehow, looking to empower themselves. Whether it be Interview with the Assassin, where there are people that feel like they’re of no value in the world and they go to insane lengths to be important in the world, even though it’s in a bad way. The same with The Lucky Ones — these three soldiers who are nowhere, they’re just these pawns in this huge game that they don’t quite understand. So they bond together in the smallest, personal way in order to protect themselves and find something meaningful in their lives.So there are threads through all these different stories that are the same, but the genres are very different.

Why take on an assignment you have to write, which takes longer, over a directing gig? Because it might be a story that I’m interested in; it might be something that will lead to directing it, so you can control the structure, the DNA of the movie. Sometimes it’s a quicker job potentially’ whereas you can get onto a film and direct it, but you’re going to be spending a long time waiting for actors’ schedules to clear, changing the script — and getting all the stars lined up to get a movie made is a lot harder than a few people deciding you can write that screenplay. With that, you have a certain authorship too, some control.

Sometimes you haven’t found the right film yet. Because film is a real expression of who you are as a filmmaker. There are plenty of scripts that you’re not certain of: “Is that the one?” So just to get on that train with one of them, only to find it’s not the one…

What’s next? I don’t know what’s next right now. I have a couple of things that are pending, and again, some of them are very small and personal, and some of them are bigger movies.

I’m so into Limitless right now. We’ve just been working all hours — almost twenty-four hours yesterday, so when you ask me what am I doing next, I’m thinking, “I’m going to get some lunch — that’s what I’m going to go do.” [Laughs]

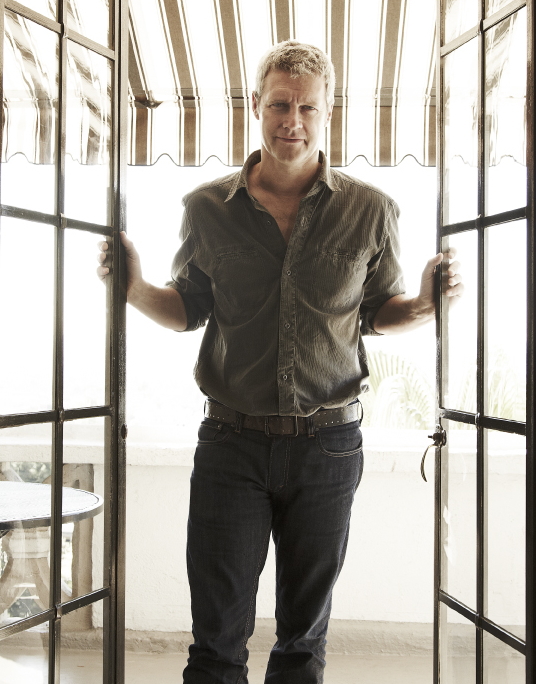

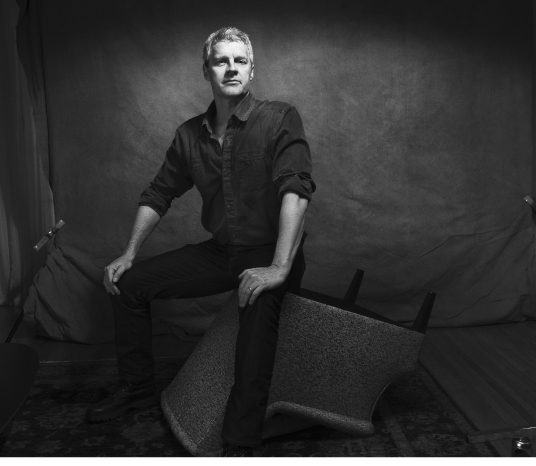

Neil Burger was photographed at the Chateau Marmount in West Hollywood, California.