“At the time,” he says, “I remember people thinking, ‘What? What are you doing? Why are you doing that?'”

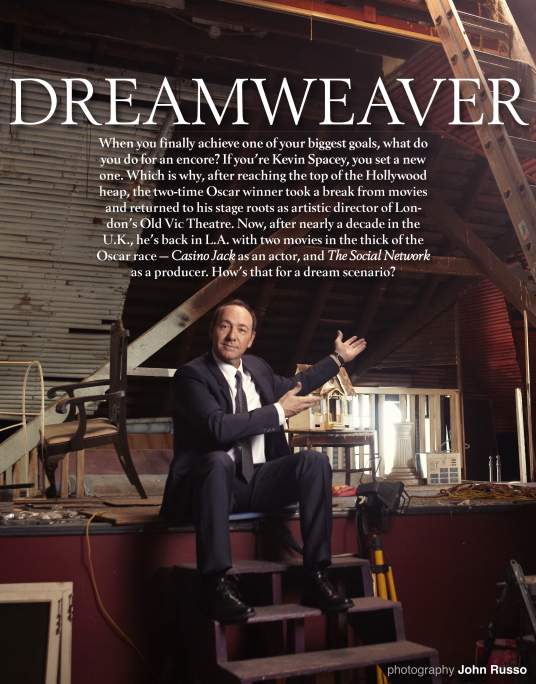

Keeping people guessing may appeal to Spacey, who is famously guarded about his personal life, but the impetus behind his seemingly mercurial choices is not to confound others, he says, but to ensure that he never succumbs to complacency.

Which is why, even though some were surprised by his decision eight years ago to accept the position of artistic director of London’s storied Old Vic Theatre, Spacey saw the move as a natural extension of his work with Trigger Street, the production company he established in 1997. It was an opportunity for the Julliard-trained Tony winner to draw upon his extensive stage background; as well as an affirmation of his commitment that once one goal has been achieved (in this case, movie stardom), to set his sights on a new one.

Although he continued to act in the occasional film — including a spirited turn as arch-villain Lex Luthor in the 2006 release Superman Returns — Spacey has spent the majority of the past decade reviving The Old Vic. Established in 1818, it is the oldest working theatre in England, but at the time he became involved it was something of a wilted rose since its heyday as the site of landmark productions starring Michael Redgrave, Edith Evans, Laurence Olivier, John Gielgud, Judi Dench and other British stage legends.

The first years of his tenure proved challenging, when he faced daunting criticism from London theatre purists. Low points included a troubled production of Arthur Miller’s Resurrection Blues, directed by Robert Altman and starring Matthew Modine, Maximilian Schell and Neve Campbell, which closed after a brief run the spring of 2006.

At the time, Spacey says, “I just realized that, for some people, unless I came riding down Waterloo Road on a white horse with Laurence Olivier standing on my shoulders, they were not going to like anything we did for a while, but we’d get through it — and we did.”

Indeed, several subsequent Old Vic productions, including stagings of The Philadelphia Story and A Moon for the Misbegotten — in both of which he played major roles — have been successes. In addition, he has fostered ambitious arts education and talent development initiatives, and a 2011 production of Richard III, to be directed by Sam Mendes, with Spacey in the lead, will include its own educational component as part of the play’s run.

For his contributions to British culture through The Old Vic, Spacey earned a rare distinction last November when he was named a Commander of the British Empire at a ceremony presided over by Prince Charles.

This intersection of arts and politics is familiar territory for Spacey, who for many years has balanced his acclaimed film and theatre career with the support of Democratic candidates and causes. His comfort in the two realms came in handy on his latest movie, Casino Jack, for which he was recently nominated for a Golden Globe for best actor in a musical or comedy. Spacey stars as Jack Abramoff, the former lobbyist for Indian gaming whose larger-than-life personality and dubious practices — including bribery and fraud — made him a symbol for Washington corruption and eventually landed him in prison.

Although he reveres classical theatre and effuses over such Hollywood stars of yesteryear as Spencer Tracy, James Stewart, Henry Fonda and, especially, Jack Lemmon — whom he first met in his teens, went on to work with several times and cites as a major influence — Spacey scored the part of Abramoff in a distinctly 21st-century manner. In the spring of 2009, Casino Jack director George Hickenlooper (who died unexpectedly last October at age forty seven), wrote in a Facebook post that Spacey would be the best actor to play Abramoff. The message found its way to Spacey’s Trigger Street partner, Dana Brunetti, who friended Hickenlooper and began a communication that eventually led to Spacey taking the role.

Facebook is also at the heart of one of Trigger Street’s most recent — and most successful — productions, surefire Oscar contender The Social Network. Spacey and Brunetti developed the project through their relationship with Ben Mezrich, author of the 2002 book Bringing Down the House: The Inside Story of Six M.I.T. Students Who Took Vegas for Millions, which was adapted into the 2007 film 21, in which Spacey starred. Screenwriter Aaron Sorkin adapted The Social Network from Mezrich’s 2009 book The Accidental Billionaires: The Founding Of Facebook, A Tale of Sex, Money, Genius and Betrayal. Spacey and Brunetti collaborated with Mezrich from the outset and eventually brought the project to Sony, where it became one of the most acclaimed films of 2010.

When Spacey spoke with Fade In, he was a man straddling two worlds. Although largely absent from Hollywood for the better part of a decade, he was keen to talk about Casino Jack and The Social Network, as well as another film, Margin Call, about the 2008 financial meltdown, due later this year. At the same time, he was busy preparing for his upcoming stage commitment to Richard III. The good news for fans of Spacey’s film work is that, although the play will take up much of his attention for at least a year, he seemed to be looking forward to spending more time in front of the camera when that experience was through.”Other than [the 2008 HBO movie] Recount, [Casino Jack] is really the first film [in a long time] where I play a central character,” he says. “I just didn’t have time to. I had to focus myself on the first five years at The Old Vic — really, primarily on that. So film parts that were cameos were all I had time to do. But now we’re in our seventh season, and things are going very well, so I’m beginning to focus a little more on film.”Welcome back onboard, Commander!

We hear you’ve added a new title to your resume: Commander. How did this come about? [My producing partner] Dana [Brunetti] says I’ve been commanding for a very long time, so he doesn’t think anything is going to change that much.

What is a Commander? It’s an honorary Knighthood; but you are not a Sir, because you can only be a Sir if you are a British citizen, and I am not a British citizen. I’m a resident.

And Prince Charles presented this honor to you? It was a very lovely ceremony, and I was very honored that Prince Charles asked if he could do the ceremony. Because the way it normally works is, you are told that you’ve received it, and then some Minister usually gives it. Because I had been an Ambassador for the Prince’s Trust for [over] a decade and done a lot of events on his behalf to help raise money and we’re doing something for him next year with Richard III and the young kids that he is involved with in that organization. He wanted to do it so I was very honored and very moved.

Well, you’ve had quite a few highs in your life and this must have been one of them. It was lovely and very nice to be able to share it with my friends and colleagues.

Are people calling you “Commander” now? Yeah, just as a joke. Commander K. [Laughs]

“My mother, when I was very young and repeatedly through my life, had this really great motto, which was, ‘Honey, if you are lucky enough to have a dream of yours come true, make sure you have another dream.’”

“Even if a movie is made with all the techniques in the world, but you never want to see it again – films that are the ones we adore and watch again and again and get more out of it every time we see it, are the films that stand the test of time. Our standards have lowered. It’s increasingly difficult to raise money for independent film. It’s increasingly difficult for independent film to get a good release, which then makes it increasingly difficult for independent films to make money, which then makes it increasingly difficult to raise money for independent films.”

It is fascinating that you made the decision, at the height of your film career, to move to London and rebuild a company for a prestigious but rundown theatre. Yeah. Ultimately, it’s been the thing that’s made me happier than I could have imagined. And I wouldn’t trade that for anything. And being able to still have one foot securely placed in the film world, to be able to produce and be a part of films like Social Network is, I have to say, all because of Dana. But again, I delegate. I believe in delegating. I believe in trusting the people you hire. And I’ve tried to do that, and I have very good people.

Was it important for you to keep your film production company, Trigger Street? Yeah, it was important. I wasn’t sure whether I would be able to, and I don’t think if I had had anybody other than Dana — who is a fighter, and who always would fight in the best interests of the company — I am not sure. I don’t think I could have possibly done it without him, because my focus had to be on what I was starting there.

So what was the catalyst that made you take the position? I don’t think it’s any different than the decisions that I, for some reason, found myself making my entire life.

You see, it stems from my mother. My mother, when I was very young, and repeatedly through my life, had this really great motto, which was, “Honey, if you are lucky enough to have a dream of yours come true, make sure you have another dream.”

So here I was at a point in my own life where I had this dream of trying to build a film career and be an actor. By ’93, ’94, I started to get roles that were fantastic parts, and I was working with incredible directors. Then all of those movies came out in ’95, and there I was. And I stayed on that horse until ’99. At the end of ’99, American Beauty had come out; I’d just done Iceman Cometh on Broadway. And then the production transferred from the Almeida Theatre to The Old Vic. And lo and behold, we were coming to London to do the London Film Festival premiere of American Beauty and I said to Sally Greene — who was our Chief Executive at The Old Vic and had asked me to come on this committee — “Look, I have one night off and I’ve tried to be helpful and useful, and I’ve done quite a lot of research and looked at what The Old Vic has been, and particularly the last thirty years” — which have been a really difficult period for it, because it was just essentially a place you could rent. It had no company, it had nothing; it was not finding audiences unless there was a particular play that was working.

This building has been the most important cultural landmark, because it’s not just that it was built in 1818 and is the oldest working theatre in London, it’s not just that it was the home of Shakespeare way before the Royal Shakespeare Company was conceived. It’s where John Gielgud made his debut in 1928. It’s where Olivier and Ralph Richardson ran it in the 1940s. It’s where everyone from Judi Dench, who made her debut on that stage in 1957, on and on and on, to Olivier having the National Theatre housed there for fourteen seasons. And here it was, thirty years of it being off the map, no longer a destination.

I will never forget the day we decided to take The Iceman Cometh there; we had been in this other theatre in the West End, this fucking horrible, crap theatre. I was standing in the middle of the stage listening to the sounds of traffic outside, thinking, “Ah, it shouldn’t be here. Is The Old Vic available?” Because I always loved The Old Vic.

And literally I said this to every person, and everyone said, “Oh, no, you don’t want to go over there, it’s on the other side of the river, it’s very hard to fill.” I said, “What? Wembley Stadium is farther, and they fill that, so maybe it has to do with what’s happening on the stage.”

I thought, “Well, there is my next dream. That makes sense to me: to not find myself in the position of being somebody who’s going to chase the same dream I’ve been chasing for ten years and try to stay on those lists and have those big hot movies and be that guy.” I thought, “Well, I have this incredible opportunity to take all of this incredible good fortune that I’ve had and put it toward something that is no longer about my career. It’s no longer about my ambition, it’s outside of it — it’s about a company.”

I’m very fortunate because the people who I’m closest to, who’ve been in my life and been a part of my career, have always gotten me. So nobody was terribly surprised, and everybody supported it.

Even your representatives? Absolutely.

Really?Yeah.

Because obviously that affects their bottom line. Well, I’m not going to say there wasn’t difficulty. Certainly there was enormous difficulty for [my assistant at the time] Dana, because I basically sort of went “Here, I want you to run the company. I’m going to London.”

He told me he was pissed off for about a year. Yeah, because — well, and in all honesty, when he came to this town, he didn’t know anybody, he had been my assistant. He had no track record. He didn’t have any credits. So I threw him into the water, all right? But in a way, [maybe] that’s why he has ended up doing as well as he’s done, because if I was here, I would have been taking all those meetings. He had to fight and struggle to build the company to the point where we both wanted it to be.

In all honesty, I thought the company was going to take a hit. I knew I had some things I had to get done in film. I wanted to do the Bobby Darin film [Beyond the Sea], and I knew if I didn’t do it I’d be too old for it, even though [critics] still said I was too old for it. And so I had a lot to learn and prepare for, and it wasn’t really until I was into 2003 that I was beginning to get an idea, because by then I was speaking to artistic directors very off the record, because they didn’t want to announce it until they were very close to doing it. I didn’t want to announce it in 2000 and then have four years go by before I actually showed up.

Plus, I wanted to lead the story and not follow the story. So we kept it a secret for about almost four years, which is pretty brilliant, because I was sort of functioning as a board member, but what I was really doing was staffing, raising money and making decisions that were about how can I run this incredible building. As I was saying a little earlier and I didn’t finish my point, this building is where not only the National Theatre began, it’s where the National Opera began, the National Symphony began, the National Ballet began — all in The Old Vic. It was and is the best decision I ever made, because it allowed me to still make movies. I don’t give a shit about whether anybody thinks I am on the list or I am da-da-da; all that stuff is outside of the work. I really care about the work. It has been the most challenging, the most engaging experience to have a staff. I have people who are running departments, people who I delegate to, people who I trust, people who bring me incredible ideas. [It’s been amazing] watching how our education department has expanded now to the point where it is the largest educational program of any theatre in London.

Now we’re in our seventh season of work, the thirty-eighth or thirty-ninth production on the main stage, of which I’ve starred in six, directed two others. People that have come and worked with us, the directors that have signed on, the talent that have come over from the States — and the fact that no matter how tough it was when we began, there is one group of people who welcomed us, came early, came often, never doubted, and that was the British public. The British public started coming very early.

You don’t quite understand what a tough assignment it is to have a 1,040-seat theatre. We are often compared to the Donmar [Warehouse] and to the Almeida and to the Royal Court — beautiful, wonderful theatres, very well-subsidized theatres, as well: 400 seats, 282 seats, 500 seats; 1,040 is a lot. So in terms of programming, and in terms of the kind of plays you put on, in terms of at what point you do them, in terms of the budgets, I had to come up with an economic model where we could survive, even though we receive no public subsidy at all.

We got one, they didn’t even call it a public subsidy; they called it a sustained grant we got last season from the Arts Council, which is lovely, I am not against it. But why — people always say, “Why didn’t you go for subsidy?” or “Why don’t you get subsidy?” I said, “Look, The Old Vic was a booking house. It didn’t step into someone else’s role. It was a place you could rent. So the Arts Council wouldn’t have been giving it money anyway, because it wasn’t a producing company. That’s number one.

“Number two, if you allow yourself to get public subsidy, and then rely on it, what’s going to prevent a new government from being elected and then they come in and make lots of cuts?” And that is exactly what’s just happened. The British government announced in October that they’re cutting 30 percent of the arts budget across the board over the next four years.

Now, I am not smug about that. I am happy that I have managed to prove that you can run a major British institution without public subsidy. At the same time, I am a very high-profile person, so a lot of people were willing to have dinner with me and eventually write checks.

There are a lot of smaller venues at rural cultural centers, places across Great Britain that do not have someone like me. They are going to be devastated. Seriously, we may lose 100 places of culture.

How do you prevent that? There’s two ways to do it. The first is, they have to change the tax laws. If the government wants to say to those of us in a position — who are out there trying to raise money for us in culture — it’s got to be philanthropy, it’s got to be contributions from individuals, OK. Then you have to make the tax situation better for them, give them an incentive, as they have in the United States, because you see, whether it’s in Houston or New York or Chicago or Seattle or San Francisco,in terms of opera or art galleries, there are floods of money that go into these organizations, right? Because, as you probably know, the National Endowment for the Arts does give out money. but they parcel it out in such small bits that it doesn’t really have the kind of effect of change and progress for companies, even particularly struggling companies now in the economy.

So I say, “Fine, I’ll go out and I’ll absolutely bridge that gap,” because I believe that there is an economic argument to make about why the creative industries are a valuable thing to invest in — economic, not, “Oh, but we’re a nice little charity, and we do good work, and it’s good for people’s souls.” Fuck off.

So one is, the tax laws have to be changed to [bring incentive to] philanthropy; and, two, we have a thing there [in Britain] called the National Lottery, and right now the profits for the National Lottery are all going to the Olympics, because the Olympics are very expensive.

But after the Olympics, in order for these companies that are about to be devastated, give them a lifeline. I want the government to consider, after the Olympics, 30 percent of the profits from the National Lottery go toward arts and culture. It’s a tax, but it’s a willing tax.

Are you out there advocating for this? Absolutely, I am knocking on the door of Number 10 [Downing Street, residence of the Prime Minister]. In fact, I was very pleased. We did a big benefit July 1st in London at the Battersea Power Station — it’s a huge old power station that’s been there for a long, long time, and I have been basically stalking Paul McCartney for the last four years to do a concert for us to raise money for The Old Vic, and he finally agreed. And so on that night, he not only did this remarkable event for us, but I got Nick Clegg, who is the Deputy Prime Minister, to come and give a speech, as well as Ed Vaizey, who is the Cultural Minister.

Because I wanted someone in the new government to go on the record about the arts, and he said a lot of things that you would expect him to say, but on the record talked about how important and how valuable it all is. So my argument to them is, you can’t have it both ways. You can’t cut thirty percent of arts across the board and then do nothing to help us raise that difference. So, yeah, I am doing a lot of lobbying.

Ironic. Guess portraying Jack Abramoff in Casino Jack came in handy then? Very ironic, indeed.

In Casino Jack you expose the hypocrisy that is Washington, D.C., and our political process. In the HBO film Recount, about the 2000 presidential election that resulted in victory for George W. Bush over Al Gore, you exposed another aspect. You also have Margin Call slated for next year, which is about the onset of the financial crisis. Is it important for you to be able to say something in some of the films you’re doing now? In all honesty, I [like] these kinds of stories that in some ways illuminate difficulties and problems that we have as a country, whether it’s how our elections are determined or how money and power influence are eroding our political system to such a degree that special interests overpower the individual… What our elected representatives are supposed to represent.

Or with a film like Margin Call, not do what is an easy thing to do, which is to label all bankers as horrible, greedy, monstrous people. But to humanize and understand from the perspective, at least of the character that I played, who was not a big CEO, not somebody making gazillions of dollars, but [somebody who was] was taking orders.

I tried to bring some level of personal accountability about what happens to people as individuals when either faced with, “Oh, I can make this decision, and this is a good decision, or I can make this decision, and it’s a bad decision.” Or those people like Abramoff, who maybe didn’t really even see what he was doing because he was living in a culture and a climate where it seemed to be happening everywhere. As he says in the film, at some point, justifiably, you know, “Everyone is selling access on K Street. That’s what they’re accusing me of doing, that’s what everybody does.”Well, yeah, he’s probably right. But again, here’s a character who was vilified, who was unceremoniously thrown under not just a bus, but probably a train, who was labeled as the most greedy, devil incarnate, worst human being that ever walked the face of the Earth, which is lazy journalism.

Have you seen the finished film? I have recently seen Margin Call, so it’s actually in my head about what we’ve done and how it’s come off. And you could not, literally, find two more contrasting characters. I aged up for Margin Call. The guy has been with a firm for thirty-four years and handles 200 guys. A character like Jack Abramoff, who is just this larger-than-life character. So I suppose through the work, these are things that I find interesting and challenging to tackle. They are about our time. But then I spend a great deal of my life in London doing theatre that is of another time. Doing [plays based on] Richard III. So I am finding a real joy in balancing these worlds.

Abramoff is now out of prison. Has he seen Casino Jack? I don’t know.

You haven’t been in contact with him? I have been in contact with him, but I don’t think he’s seen it. He has not said to me he’s seen it. His children have seen it, and they’ve told me how they feel about it, and they are very pleased that I didn’t play him as a caricature and they felt that [my portrayal] was very fair.

How much of his story did you know going in, and were you surprised that it wasn’t as black and white as the media reported? I didn’t know a lot. I remembered the story, but I wasn’t heavily focused on it. I was living in England at the time when it broke, and when his trial was happening, so it wasn’t news in England. I vaguely remembered it. I knew who he was. I had met him at some point in the ’90s in Los Angeles.

I didn’t know a lot. George [Hickenlooper] met him a number of times. I decided not to do a lot of research until after I met him, because I didn’t want to, sort of knowing that it had been a very notorious story and it was the biggest scandal in Washington since Watergate and all. I thought, “All right, there is going to be a lot of commentary. I just want to meet the man.”

So I met the man, and what I took away from that was more about personal issues and feelings and characteristics and not about “Did you do this, or did you do that.” because I knew I could sort that out later.

And then I met with a lot of people that knew him and worked with him: other lobbyists, friends of his, people that hated him, people that thought he should be dead. There is a whole gamut of people. Then I started to unearth the coverage and trial transcripts and things like that. And that’s when I went, “Wow, how do I reconcile all this enormous amount of things that have been written and said about him with the man I met with all the other things that people had said about him, some good, some bad?” That’s when I started to go, “OK, so wait a minute. He is supposed to be the [most evil] person that ever walked the face of the Earth, and he is supposed to be the greediest person ever. But he wasn’t paying his mortgage? He didn’t have his own private jet. He wasn’t living high on the hog. He didn’t have a Swiss chalet. He wasn’t spiriting his family off on fabulous vacations. OK, so where did the money go?” And then you start to unearth, “Oh, the money went to a lot of things that he believed in and a lot of things he wanted to support and a lot of people.”

Now, none of this takes away from what he did. He is not a hero. He did some things he shouldn’t have done. He crossed the line. There is no doubt. But when you measure it up against the way he was framed — and not framed-framed, but framed in the kind of person he was — I understand why, when the judge was about to sentence him in Florida, that normally under those kind of circumstances the judge might get two or three letters from outside people saying, “Will you show leniency to this defendant?” — there were 200 letters from many people who Jack didn’t even know but that he had helped in one way or another.

So I found a complexity. “So he is not this villainous, evil thing; he is a human being, he is a person who made some good and bad judgments and good and bad decisions.” My job is to try to get into those shoes. My job is not to judge. My job is not to sit outside and point fingers. My job is to have empathy and try to walk in those shoes and try to play a character in such a way that an audience, even against their better instincts, is going, “I like him. I don’t like him. I like him. I don’t like him. I like him…” So all of that journey of getting to that point was, with George by my side, incredible.

And your involvement was a result of Facebook? Yeah, talk about irony. I was cast in this movie on Facebook. It cracks me up, but it’s true.

What happened? Someone told Dana about it; “Hey, have you seen this thing George Hickenlooper has put on his Facebook page?” So Dana went and looked at it. Then he called me and said, “Do you know about this movie?” And I said, “Well, no. I know who Jack Abramoff was, but I don’t know about this movie.” So then Dana called George, and they started talking, and then George and I started talking, and then George got on a plane and came to London.

That is ironic. What did you think when Dana first came to you with the idea for The Social Network? Oh, well, it wasn’t even a book yet. It was an idea that Ben Mezrich had. He came to Dana four years ago now, or something like that. Dana’s reaction at first was, “How is that a movie?” But very quickly, when we began to understand the complexity of it, that there were these three lawsuits going on, that it actually had the hallmarks of what makes great drama: friendship, betrayal, invention, power. Then we realized that, “Oh, maybe this is a film.”And then the book proposal leaked. Everybody was talking about it, and we decided we did not want to go through what we went through on 21.

Which was? We had sold 21 to MGM. MGM didn’t tell us they were being bought. We got parked for four years, and we felt during that period of time as movies about Vegas and TV series about poker [came out] that we fucking missed the boat.Now, it turned out 21 did very well; but we weren’t the first out of the gate. And with this story about something that has revolutionized our world and it had all the classic sort of earmarks of an incredible story that would not only capture its time but maybe be timeless, we felt like you don’t want to miss this moment. That’s why we decided to go out with the book proposal even before Ben finished the book.And we had a great relationship with Sony, [producers] Mike De Luca, Scott Rudin. And then Aaron Sorkin came on. And so literally it was a very interesting situation, because Ben was finishing the book while Aaron was writing the screenplay. So, you know it’s based on the book; [laughs] it’s like it wasn’t quite done.

“Aaron Sorkin said, ‘Look, life doesn’t happen in a certain narrative, life doesn’t happen in dialogue, life doesn’t happen in scenes; that’s what we do; we dramatize.’ So Social Network is dramatized, but the facts are the facts. These people went before depositions and raised their hand and swore to tell the truth, and the stories don’t match. So let the audience decide.”

“I don’t think that people present themselves on Facebook or on Twitter as they actually are. A lot of people aren’t even using their real names on Twitter. I don’t think that you’re ever going to get to know somebody the way that you can get to know somebody sitting across the table from them and having a real, genuine conversation than you possibly could in 140 characters.”

What do you make of the criticisms that the film is wildly inaccurate in places? All I can say is that it has been as [exhaustively] sourced as you could imagine a film to be, has probably a phalanx of lawyers from the studio. It’s been exhaustively researched. It’s been — there’s lots and lots and lots and lots of people that were talked to.

Now, why did we tell the story in the way we told it? Because it’s like Rashomon: you’ve got two people who were in a room seven years ago and disagree about what was said or what happened. So we don’t tell one point of view; we tell multiple points of view. And for those who argue that, “Oh, it’s dramatized,” that’s what we do. You have to make the argument that Peter Morgan, who wrote the screenplay for The Queen, certainly wasn’t hiding under the bed in Buckingham Palace listening to the Queen talk to her husband about their daughter-in-law; but you source, and you dramatize.

Aaron Sorkin has said, and quite brilliantly, “Look, life doesn’t happen in a certain narrative, life doesn’t happen in dialogue, life doesn’t happen in scenes; that’s what we do: we dramatize.”

So it’s dramatized, but the facts are the facts. These people went before depositions and raised their hand and swore to tell the truth, and the stories don’t match. So let the audience decide.

So you never heard from Zuckerberg? No.

Are you fascinated with the public’s growing obsession with fame, especially with social media sites like Facebook and Twitter? Do you understand it? Well, I just think it’s a false reality. I don’t think that people present themselves on Facebook or on Twitter as they actually are. In the first place, a lot of people aren’t even using their real names. That’s certainly true on Twitter; it’s less true on Facebook. So there is an anonymity to it, which I guess has good sides and has bad sides. But I don’t think that you’re ever going to get to know somebody the way that you can get to know somebody sitting across the table from them and having a real, genuine conversation than you possibly could in 140 characters.

Right. Well, of course. Aaron actually said a very funny thing about it. He goes, “People are presenting their best qualities, right? And I am afraid that one day my children are going to find themselves shocked that human beings have flaws.”

You’re coming up on nearly twenty-five years since your film debut. How has the Hollywood system changed for the better or for worse? I had this experience at the AFI tribute to Mike Nichols in June where what’s really great about that particular event is they show really long extended clips. We were watching Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? The Graduate, Silkwood, Angels in America, Carnal Knowledge. I turned to my manager, Joanne [Horowitz], who was with me, and said, “Why aren’t we making movies like this anymore?” Occasionally we are. We’ve just produced one: The Social Network. There are no car crashes. There are no gunshots. There are no chases. There is no 3D, no animation. There are people having relationships and talking. It proves that sometimes it’s enough if you bring the right elements together. I wish that those elements could come together more. I wish that we weren’t making films that were so disposable.

Even if a movie is made with all the techniques in the world, but you never want to see it again — films that are the ones we adore and watch again and again and get more out of it every time we see it, are the films that stand the test of time. Our standards have lowered. And that’s disappointing. It’s increasingly difficult to raise money for independent film. It’s increasingly difficult for independent film to get a good release, which then makes it increasingly difficult for independent films to make money, which then makes it increasingly difficult to raise money for independent films.

Has it always been that way? Well, I don’t know. If you go back to the ’70s and you look at Hal Ashby and you look at Robert Altman and you look at Dennis Hopper and you look at [Francis Ford] Coppola…even though everyone wants to stand and call them rebels and outsiders, they figured out a way to work within the system. They figured out a way to make studio films that were phenomenal and are still with us to this day.

I wish the studios supported that kind of filmmaking. It’s not that they don’t find it. The fact that Sony produced Social Network, we were absolutely delighted, and I will praise [Sony Pictures co-chairman] Amy Pascal until the day I die for having had the guts to do it, because it’s not the kind of movie they generally do.

I do think there has to be an argument to those in positions of where the money goes: If you make so much money on these big tent-pole movies that all the kids are going to, then have your divisions that make other kinds of films. We have even lost those divisions in the last decade — a lot of them.

Now, what studios might do is see a film at a film festival and pick it up and release it. The studios should be making these films, be proudly standing next to these kinds of films. That’s one of the reasons why Sony is so delighted and proud at Social Network. They are proud they made it. They should be, and it should be an example.

This is what moviemaking is: great writing, great acting, great direction. But we seem to be in a place where lots and lots of disposable comedy and things that…I don’t have any problem with technology and with advancements in what we can do on film. What we can’t do is to replace or think that replaces good storytelling, and as always you have got to fight for it. So the fight goes on.

Most actor shingles aren’t able to achieve such success. What do you attribute your run with Trigger Street to? When I started the company, I was really determined that it not be a vanity company. Let’s face it, sometimes studios or other companies make deals with actors to satisfy, you know, having a company and a staff and buying a book every now and then but not necessarily actually producing anything, but it’s to keep them in the wheelhouse of the big franchise movies that they may well be doing and acting in for the studio.

It wasn’t about that for me. It was about wanting to find a way to do for others what had happened to me. Because I wouldn’t have a film career if it weren’t for first-time writers, first-time directors, first-time producers, taking a chance on me. And if you look at the films we’ve done, a lot of those are first-time directors, first-time writers, in some cases the first big role for certain actors. That was what was important to me to try to build.

I, of course, hoped that we would build the company to a point where we would be doing movies with studios and doing films that have done so remarkably well as Social Network — it’s incredible. And what I am proudest about in Social Network is I am not in it. I didn’t have to be in it!

And now you have another successful company with a film heading to the Oscars. Will you ever direct again? Yes. I’ve directed plays. It’s a little hard for me to tackle that idea at the moment, because I am about to be doing Richard III for ten months and into at least nine cities, as well as New York and London. So that’s going to be occupying my time, and if you direct a film, it’s a year commitment. So I see it, but not quite yet.

Are you a workaholic? No — well, maybe, maybe. But I would say this: I love to enjoy the spoils of work. I want to have as good a time when I am not working as when I am working, and I want to enjoy the work. And I have become much better about that since I’ve moved to London than I ever have been. In the sense that I have made it a point to carve out my own time that is not about work, and that’s made it that much more enjoyable.

That must be hard, though, because it seems like you have so many balls in the air. There are a lot of balls in the air, but I only really feel it when I am in a situation like I am in now, where I have got plays at The Old Vic that are opening, I have got this movie I am rolling out, so I am going city to city and doing screenings and Q & As and interviews and talk shows and yada-yada. You know, at the end of two or three months of that, you start to feel, “Wow, there’s a lot going on.” But on a day-to-day basis, I am able to handle it, because I have these remarkable people at The Old Vic, I have this remarkable producing partner at Trigger Street and I have got great people in my life, in terms of who my reps are.

When is your tenure at The Old Vic up? The gig at The Old Vic is supposed to end for me in 2015, meaning the beginning of that season, which would mean my last season would be 2014 into the beginning of 2015.

Have you given any thought to what your mom advised; Do you have another dream? Yes, I have. I’ve already started.

Care to share? No, not yet.

You’re producing, acting, directing the most prestigious theatre company in the world, lobbying on behalf of the arts… What, if anything, would you change about your life right now if you could? As hard as I try, I don’t seem to be able to do enough. It’s hard to keep it all together. I am doing the best I can to not have it fall on the ground. But I wish I could do more, and I wish I could be more helpful, and I wish I had more time. But I don’t — but I’m doing the best I can.