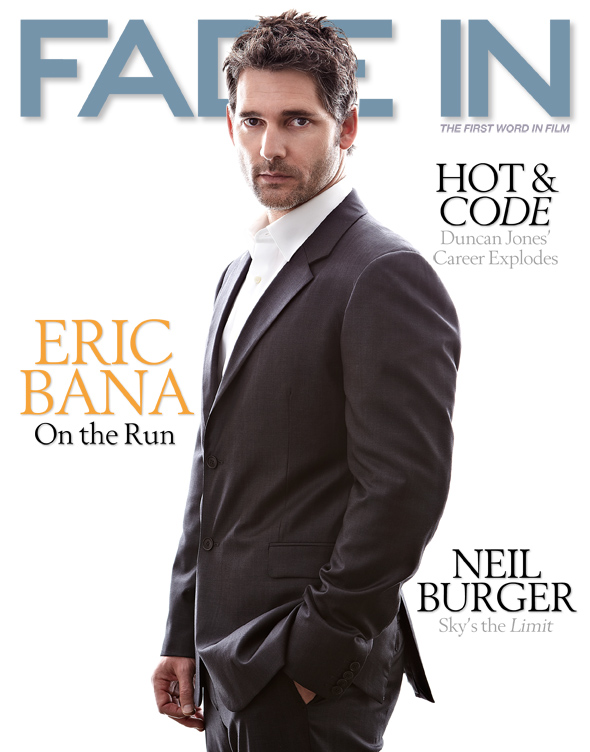

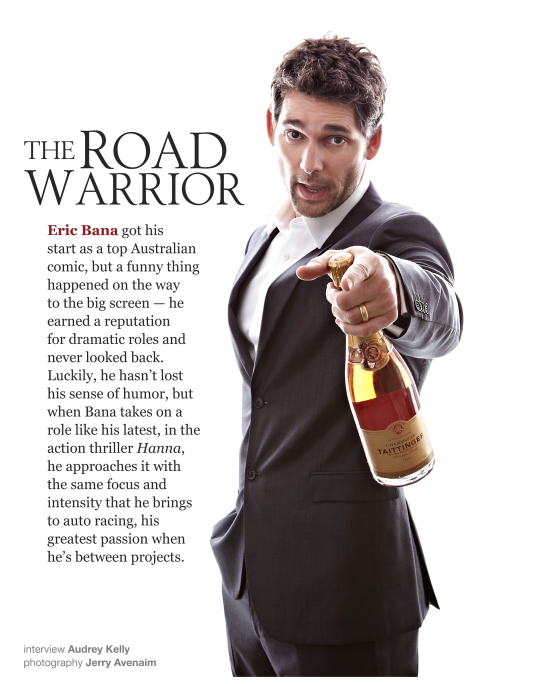

Usually, performers known for their comedic chops yearn to show their range by starring in a dead-center drama — think Bill Murray in The Razor’s Edge or Jim Carrey in The Truman Show. Bana is the rare inverse: a guy with a serious gift for gags who made his first splash in dramatic roles and has seldom strayed since.

Not that he seems to mind. On the contrary, Bana has never been one to brood over his plight — and wisely so: he’s been directed by the likes of Steven Spielberg, Ridley Scott and Ang Lee, and his movies have earned north of a billion dollars in the U.S. alone. Instead, like so many Aussies, he exudes a “no worries” nonchalance, spurning long-term goal-setting in favor of taking things as they come. He doesn’t even employ a manager because, he says, “I don’t know exactly what they would, or could, do for me. I’m a pretty headstrong person who has strong instincts on what they like to do.” Which may help to explain his filmography — an eclectic mix of studio tentpoles (Star Trek), earnest costume dramas (The Other Boleyn Girl) and, yes, the (very) occasional comedy (Funny People), but no evident through-line.

To better understand Bana, it’s worth considering his greatest passion outside of acting — auto racing. He’s been obsessed with cars since childhood, and even directed a documentary, Love the Beast, about his twenty-five-year relationship with his 1974 Ford XB Falcon Coupe, a.k.a. “The Beast,” which he bought at age fifteen and still owns today.

To do them well, both acting and racing require dedication, sacrifice and a willingness to take risks that may not always be rewarded. But for Bana, the sheer pleasure he derives from being behind the wheel, or inside a character, would make pursuing them worth it, even if he never achieved success at either. In other words, he may come across as an easygoing bloke, but it’s clear that when he sets his mind to something, he’s as intense an Aussie as you’re likely to meet.That intensity served the married father of two well in such roles as Sgt. “Hoot” Gibson, the Delta Force soldier in Black Hawk Down; David Banner, the tortured scientist in Hulk; Hector, the rugged Greek warrior in Troy and Avner, the brooding assassin in Munich. And it was put to plenty of use on his latest project, the action thriller Hanna, as a former CIA agent who teaches his young daughter, played by Saoirse Ronan, self-defense and survival techniques that help her to elude capture by an intelligence operative, played by Cate Blanchett, when he must send her on a dangerous mission.

Bana’s next mission? Another thriller entitled Blackbird. Fade In caught up with the actor in Montreal, where he’s shooting the film opposite Olivia Wilde and Charlie Hunnam.

Hanna was a great choice. Oh, good. I haven’t seen the finished version, but I’m looking forward to it. What kind of film were you expecting?

I had only seen glimpses of footage previously. Had no idea it was going to be an intense, hold-onto-your-seat action thriller. I really loved the script. I thought it was pretty unique and really well written. And, dare we say it, an original screenplay. [Laughs] Just kidding.

Thank God we have more original material and book adaptations making it to the top of the box office these days, instead of sequels or comic book adaptations or reboots. Absolutely. It’s exciting to be a part of that.

Danny Boyle and Alfonso Cuaron were circling Hanna at one time to direct. At what point did you sign on? I came on after Saoirse and Cate, and Joe was already set to direct. Joe came to me to play the part of Erik, and I said yes right away. It all happened very quickly, actually.

“Even though comedy was my background…it’s not something I aggressively seek out only because I know that it would be very difficult to find something… My favorite kind of stuff is Larry David. That’s not exactly mainstream movie comedy.”

“Shooting the same scene in the underground [subway] was [the hardest part of the shoot] because it was one long shot – three-to-four minutes long – without a cut. It was a little scary, but at the same time I was up for it. It’s extremely rare. It’s exciting. It requires a lot of adrenaline. You know, where there’s a real cost for messing something up.”

What was involved in your preparation to play Erik? I was very lucky because I was at home and really fit. I was in shape. I hadn’t put myself on the fat farm or anything, [laughs] so I was ready to go. I try to have a holding pen physicality [laughs] that I maintain to make things easy when you get the phone call. There wasn’t a whole lot to be done in terms of my physicality, but there was a very different style of fighting that I had to learn in a short amount of time. But I had a great stunt guy, and we just worked together on coming up with a style that would fit my physical background, and that of the character’s. So it all happened pretty quickly.

Was it confusing in any way to have a character with the same name as yours? Once I signed on, I wondered if they would change it, but I thought it was kinda cool that they didn’t.

As a father, how much did you draw on your role as a parent in approaching your character? Once you become a parent, it’s impossible to work out which parts are, and which parts aren’t, because they just become an integral part of your life. But probably not too much. Saoirse is pretty bright herself. I never really felt like it was my job to look after her, or mentor her in any way, besides the obvious — when it came to the fight sequences, to make sure I didn’t hurt her. Besides that, no, I just surrendered myself to the story. I thought it was just a great story of youth. Not only youth, because adults can go a long time before they lose their innocence. I thought it was more of a loss of innocence in general than a loss of innocence that pertains exclusively to youth.

Are you a prankster on set? Sometimes. Prankster’s not a good word. I do like to do impressions of famous people. So I will wind up on set for co-stars but I’m not a prankster guy.

How did you wrap your mind around Saoirse’s character, a teenager, toting a gun throughout the film? It’s been reported that you dislike firearms. No. I don’t know where that came from. Maybe a misquote years ago. I was doing an interview and they were asking about guns, but I don’t have a point of reference to throw because they’re illegal in Australia. We’re not a gun culture. I didn’t grow up thinking about guns, let alone love them or hate them. They’re not part of our society.

Glad we could clear that up. What was the hardest part of the shoot? The most challenging was shooting the scene in the underground [subway] because it was one long shot — three-to-four minutes long — without a cut. It was a little scary, but at the same time I was up for it. It’s extremely rare. It’s exciting. It requires a lot of adrenaline. You know, where there’s a real cost for messing something up. And Joe has a reputation for having an iconic one-shot set-up in most of his movies. In Hanna, that was one of them. That was challenging. You have to realize it all has to be there in one shot, but it’s very satisfying, too. It’s an occasion to do something physical. You can at least look at that objectively and know, “OK, does that work or not?”

You’ve starred and co-starred in some memorable films — Chopper, Munich, Black Hawk Down, Troy and also taken a few supporting roles like Funny People and Star Trek. Intentional, or just the best roles to come your way at the time? There’s no direction. I’m an actor, and I go after parts I want to do. Sometimes they’re leading, and sometimes they’re not.

You’ve avoided taking on a manager. Why? I don’t know exactly what they do, so…

Really? I know they manage, but in my case I don’t know what a manager would, or could, do for me. I’m a pretty headstrong person who has strong instincts on what they like to do. I’d love to have someone who can pick up the slack every now and then, but that’s part of life.

Whose advice do you rely on when you make choices as an actor? [For projects,] eighty percent myself, and the other twenty would be a general counsel between my agent, my wife, and rarely but occasionally, a couple close friends who are more of a sounding board than a final vote.

Would you ever consider doing, say, a cable series on HBO, Showtime…or one of their original movies? And have you ever been approached? That’s impossible to answer. It would depend upon the project. It’s really dangerous to have hard-and-fast rules that limit your creative outlet rather than expand upon them, and I guess that was what I was alluding to before when you asked me why I had gone into that particular direction. It’s about having choices and having more choices. I would say that to anything, really.

@ILikeFilms on Twitter wants to know if, after Funny People, you are interested in pursuing more comedic roles. Yeah, I’ve always been open to it. In my [case] it’s a much, much narrower road from which to choose. Even though comedy was my background, I never saw it as my right to insert myself into the world of comedy. Because that was my background, I felt like I would wait until something came along that was something for which I could have an active competition. So it’s not something I aggressively seek out only because I know that it would be very difficult to find something else I felt was going to be a lot of fun. My favorite kind of stuff is Larry David. That’s not exactly mainstream movie comedy.

He’s amazing. I get pissed every time I watch an episode [of Curb Your Enthusiasm] because I know there’s one less for me to see.

@Bootsybah on Twitter wants to know, “Any chance of Chopper 2”? Not with me.

Do you like where you are at this stage in your career? I believe in not having expectations because I believe they’re the biggest cause of disappointment in life. I really subscribe to the four quarters. I don’t believe in dissecting each quarter. You have to let the game play out and not buy into the day to day.

My heroes are people like Robert Duvall or Sissy Spacek, who have been around for a long time, and you can look over their career in a particular way. That really is the most important thing in the long run. I do believe in having pretty short expectations, but I don’t believe in setting goals for the next number of years. It’s really dangerous. I just think it takes away a lot of your creative drive. I’d rather try to be a bit more of the moment and respond to the material that’s around or that’s not around and act accordingly.

Does that also apply to your life outside acting? Outside of my professional life it’s a little different. There are things that I really want to do and really want to see. I don’t have full control over the time frame in which things happen. I’m probably stricter with myself outside that professional [arena]. Yeah, of course I know what I want to do, but from a professional standpoint it’s not good to do, and it’s dangerous.

Are you still actively looking for projects to produce? Yeah, I’ve always been interested in helping shepherd a project — particularly at a time when there’s stuff that I want to do. You get to a point where you want to have a say in the type of material that not only you’re a part of, but the kind of material that’s actually going to be getting off the ground.

How do you go about finding projects? [They] come through people I know in the business back home. They come through my American agent. They come through my Australian agent. They come direct. But I haven’t set myself up as a producer for hire. I really do enjoy producing material that I’m really going to be involved with, because I don’t like the idea of just putting my name on things.

Producing is also very time consuming. Yes.

Why put on this other hat when you could spend your time watching football and, speaking of dangerous, racing cars? Exactly.

Nice Top Gear piece, by the way. Ah, right.

That must have been fun. It was. I know the guys, and they’ve been trying to get me to do the show for a few years. It was probably one of the most difficult things to pull off in terms of your schedule to be in England while they’re filming, with a day to spare. Kind of impossible logistically, but we managed to do it.

You crashed your car in your documentary, Love the Beast. But you actually have a few crashes under your belt now, right? When you race, you crash a lot. The crash in Love the Beast became well known because it was the car I had for a long time. It comes with the territory.

How do you continue to talk your wife, Rebecca, into allowing you to race? There’s never been a conversation. I was [racing] before we met. I’ve also never hurt myself so…she’s actually very realistic about it. She’s very well-schooled on motor racing and which races are more dangerous than others. She’s fully aware of how safe it is, but there’re risks to everything. It’s a typical cliché, especially with a big race or the Top Gear thing. The reality is, it’s safe, and I do a hell of a lot of cycling, and I feel far more vulnerable on the road [doing that] than I do in a race car.

How many cars do you have now? Half a dozen or so, including my wife’s.

How do you decide which one to drive? Some of them you can’t actually drive on the road, so it depends on whether I’m doing the school drop-off or have the dog or flying solo. So the day’s activities tend to narrow down the choices a bit.

“I believe in not having expectations [with respect to my career] because I believe they’re the biggest cause of disappointment in life. I really subscribe to the four quarters. I don’t believe in dissecting each quarter. You have to let the game play out and not buy into the day to day.”

“I believe in not having expectations [with respect to my career] because I believe they’re the biggest cause of disappointment in life. I really subscribe to the four quarters. I don’t believe in dissecting each quarter. You have to let the game play out and not buy into the day to day.”

What, if any, riders are in your contracts in regards to racing while making a film? Or is it strictly verboten? It’s never been an issue. On the one side, every film I’ve done, I’ve barely had time to breathe, let alone to hop in a race car. I have a completely different life then when I’m on a film. I drop everything and focus completely on acting in the movie, and then, when I’m not working, I’m my own boss and I can do what I want. So it’s never been an issue. You would never have time to go racing when you’re working on a movie.

Last time we spoke, you said you had an idea for a script, but you hadn’t started writing. Any progress? That was probably Love the Beast.

How do you feel about directing a feature one day? Does the idea still appeal to you after that experience? Only if it was coming from somewhere within me; [something] that I could write. Storytelling is a pretty personal thing. I tend not to read a script with that eye. Once in a blue moon I might read a book and think, “This would be cool to adapt.” But it’s extremely rare.

So you haven’t fallen in love yet? Not yet, no.

We’re going to throw out the names of a few of the directors you’ve worked with — tell us something that you gleaned from each one. Let’s start with Joe Wright, who directed you in Hanna. That you can solely execute a style when you know exactly what it is you’re trying to do. The style of the finished film is something that was really in his head. The script was really strong but the style and tone of it was something that was very, very much there from the get-go, and that was pretty inspiring.

The tone is one of the most important aspects. A film can suffer if the tone is not right, even though the script is good. Exactly. That’s really what you’re counting on a director to do. To have that point of view, that sense, that feeling, right down to the score — all the elements that make up a film — he was able to verbalize prior to the production.

Steven Spielberg, who directed you in Munich. The one thing that I learned from his direction was staying in the moment. His ability to truly be in the moment of a rehearsal or a take; the framing, the lens that he chose; the way he thinks the scene may go and to allow the moment to happen. That was a really fantastic thing to experience, really exciting to be a part of. Someone who is open and reacts to his environment.

J.J. Abrams, who directed you in Star Trek. He’s kind of scary to be around because there are two brains running simultaneously. I’ve never seen someone have such a good time while conducting an orchestra of that size. I guess that comes down to imagination and spontaneity and preparedness. They can only have that much fun and give their work that much energy when they’re really prepared and know exactly what they’re doing.

Judd Apatow, who directed you in Funny People. There’s a fine line between playing ad-lib and letting things run off the rails. Judd is great at allowing a scene to breathe, and to have spontaneity, but still remain within itself, which is the real danger with ad-lib. What Judd is fantastic at is taking those parameters within a range that works for the scene and he’s always able to do it right there. And most ad-lib accompanies rehearsal, then gets incorporated. He was the most daring director I’ve worked with in that sense. It was a lot of fun.

And you got to play an Australian. Yeah, that’s illegal.