hough each film was based on previously published material, Into the Wild, Youth Without Youth and The Diving Bell and the Butterfly were deeply personal expressions for their respective directors, Sean Penn, Francis Ford Coppola and Julian Schnabel. And all three directors fostered intimate collaborations with their stars — each of whom appeared in nearly every frame of their films — resulting in transcendent performances.

hough each film was based on previously published material, Into the Wild, Youth Without Youth and The Diving Bell and the Butterfly were deeply personal expressions for their respective directors, Sean Penn, Francis Ford Coppola and Julian Schnabel. And all three directors fostered intimate collaborations with their stars — each of whom appeared in nearly every frame of their films — resulting in transcendent performances.

Into the Wild, the fact-based story of Christopher McCandless, a young idealist who shed the trappings of his upper-middle-class background to test himself in the unforgiving Alaskan frontier, was irresistible to Penn, no stranger to defiance of social conventions. It’s difficult to imagine another major star subjecting himself to the criticism Penn endured for visiting Iraq as a private citizen to survey the damage after the U.S. invasion, and traveling to New Orleans in the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina. But his ventures may have given him greater insight into the motivations that compelled McCandless to abandon conformity so willfully. Inspired by Penn’s commitment to honoring McCandless’ memory, Emile Hirsch plunged into his character’s off-the-grid exploits and lost more than forty pounds in the process. The result: a survival tale that is as exhilarating as it is tragic.

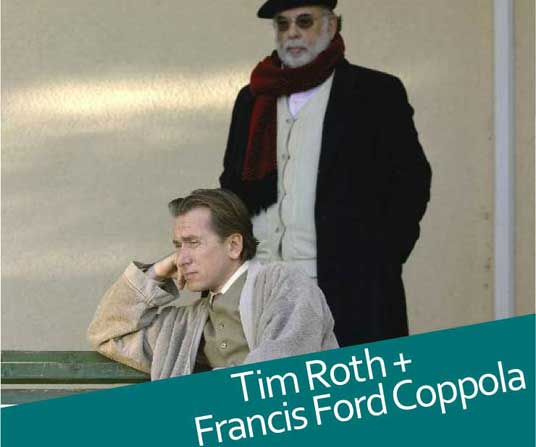

For Coppola, a Sisyphusian decade during which he strove unsuccessfully to mount his dream project, Megalopolis, gave him an innate understanding of an academic who gets a second chance at love and an opportunity to complete his life’s work in Youth Without Youth. Based on a novella by Romanian author Mircea Eliade, the film crackles with intelligence and ideas. Much of the credit for its effectiveness goes to Tim Roth, who stars as Dominic Matei, an elderly professor who, after being struck by lightning, begins to age in reverse — which required the British-born actor to inhabit Matei from college age to his nineties.

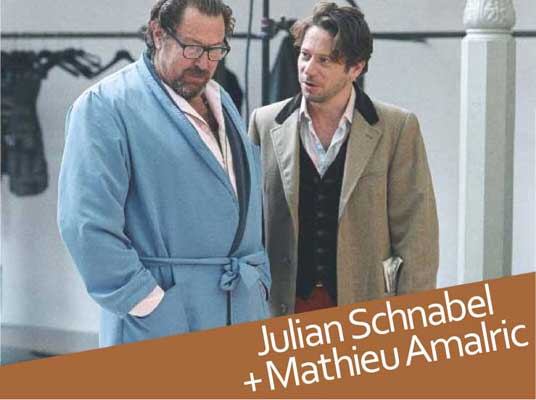

After nursing a friend whose body had betrayed him, and then struggling to help his dying father accept his fate, Schnabel brought a poignant understanding to the true story of Jean-Dominique Bauby, the French journalist who, following a 1995 stroke, at age forty-three, was left paralyzed and incapable of moving anything but his left eyelid. In an act of staggering will, Bauby learned to communicate by blinking, and in this manner dictated a memoir, thus slowly building the narrative word by painstaking word. Schnabel, who earned Best Director honors at the 2007 Cannes Film Festival for his efforts, steered Amalric through a French-language adaptation of Bauby’s book that transcends the claustrophobia of a man trapped within his paralyzed body by infusing it with humor and a profound sense of purpose.

The strength of the bonds between these directors and performers is all the more noteworthy because Penn, Coppola and Schnabel are all reputed to have egos as large as their prodigious talents. But their films suggest otherwise, because such intensity and sensitivity would not be possible without a willingness to subordinate themselves in service of material that clearly resonated with each of them on such an elemental level. It was as if they had conceived the stories themselves.

To better understand the creative give and take that led to such powerful movies, Fade In spoke with the three filmmakers and their stars for an in-depth assessment of their partnerships and processes.

hy did each of you identify so strongly with Christopher McCandless?

hy did each of you identify so strongly with Christopher McCandless?

Penn: There are a lot of ways I could answer that question. My gut instinct about where we are today as a culture is that we’re increasingly comfort-addicted. These things we call the rites of passage, which once upon a time presented themselves automatically to historic cultures, whether you’re talking about providing food through the hunt, or even tribal warring, all the things that make a man a man and a woman a woman; things that bring them to the edge of their existence, so they’re able to see where the edge is, and be humbled by that, and that is the thing that really starts a life — it’s gone. Yet here was a guy who really did it.

And while there were many other motivations, there is no territory more exciting to me than the American landscape. [I respect how] he [explored] it that way, in the spirit of pursuing that kind of freedom of his soul. Now, I didn’t feel like I was sitting there, blowing out the candle alone. I felt like it was a birthday party, and that the desire for that kind of wanderlust is so common. I remember when I read the book, and feeling like I wanted to buy up all the copies, and just go drive around the neighborhood and hand them out to everybody that I knew. That’s kind of what you do when you make a movie like this.

Hirsch: I agree with Sean; the wanderlust of it is so powerful. It was a chance to look at someone I felt really made an effort to step outside of the box and really live their life to the fullest. I admire that so much. When I hear about someone going to McDonald’s, buying up cheeseburgers and driving around the downtown part of the city and handing them out to homeless people, and just talking to pimps or prostitutes on how they might improve their lives…

These are things that McCandless did, according to the Jon Krakauer book.

Hirsch: It’s just a way of thinking, and most people don’t think that way. It was an exciting idea: Wow, you can really go out into the world and experience things. You don’t have to sit back complacently and let the world get to you. You can be active in finding out who you are, and what the world has inside of it. That is something so many people relate to, a reason the book was so successful, and why people relate to the film. There’s that desire for adventure that goes back to when you were a little kid, and you said, “I want to travel around the entire world, and I want to be an astronaut, and I want to do this or that.” It’s that inherent sense of adventure, the thirst for it that we all have inside us. Aside from loving the adventure, I loved the reminder that it was even possible. This came for me at a time in my life where I’d say that adventure wasn’t happening. I wouldn’t call it a sense of hopelessness, but there was a sense of listlessness in my life, and maybe the dream, the outline of adventure, was beginning to fade. I was starting to forget that it was even possible. Then, bang! This project, this book and script come along. It reawakened all the things that are possible in my life.

Sean, you were very non-complacent when you went to Iraq to visit hospitals. You said you made the trip because you were an American, and you were responsible. Some of the press and public, however, reacted as though you’d done something un-American. Response was similar to your recent appearances with the president of Venezuela. This backlash had to have had some effect on Into the Wild‘s box-office numbers. Do you feel that what you’ve been doing is greatly misunderstood?

Penn: What I feel is that the Constitution is ignored by those who make those criticisms. It wasn’t just a visit to hospitals. I did go to hospitals, but I did a lot of other things. The Constitution is the Constitution is the Constitution. So when people say “un-American,” about anybody… as I’d certainly say about this administration’s behavior — I’d say it’s absolutely un-American and they are very likely guilty of crimes that by existing law could have them put to death, including treason by the outing of CIA operatives. So the best way for me to answer that question is; if they want to be opposed to the Constitution, or dismiss the Constitution, then that is as close as any irrational thought comes to declaring them un-American. I can only say that I am a deep believer in the Constitution.

Is it un-American to sit quietly and watch policies enforced that you don’t believe in, or that you believe violate the Constitution?

Penn: It’s inhuman.

Krakauer described in his book the number of Alaskans who were critical of McCandless. They said he was foolish and unprepared, others said he broke his family’s heart and shouldn’t be celebrated. Sean, how do you react to that criticism?

Penn: I can’t help but feel that perspective is one of a frightened person. When fear comes out like that, it becomes loathing, and then it becomes judgment. If those people ask themselves, “Is my child here for my heart, shall I judge my child on the basis of how much he warms my heart? Or am I here for his heart? Do I want for his heart? No matter what his reasons, that may be borne to a particular sensitivity, may be traumatized by the world, or by myself, whatever he has to do, and only he knows that, to find his truth so he can feel his life while he’s living it, that’s what I want him to do.”

Emile, how about you?

Hirsch: It’s hard for me to give much of a reaction. The whole idea [that] this guy’s life shouldn’t be examined or looked at, I just don’t understand that. It’s such an extraordinary thing that he did. Granted, there’re problems that people have with the way he did it. But to not examine that is judging a character, a person. Then any movie or book that’s made, you have to agree with every single thing that a character does. That’s ridiculous.

So it’s not about judging, it’s about accepting?

Penn: This is a journey in shoes few people have walked. And we all know the expression related to that.

Sean, you said that you felt that the loss of your brother Chris, who died in 2006, made the McCandless family feel you would understand their loss and perhaps that helped them trust you, finally, with this story. How did the weight of your own tragedy influence how you told the story onscreen?

Penn: I don’t analyze that kind of stuff. Your life happens. I’m not going to break down how you feel things in your heart and in your head. You feel it everywhere. Thoughts can be very provocative, and finely thought and expressively related to one’s own life. So whatever happens in my life, and the lives of the people who contribute to my films, the actors, the cinematographer and the experience we share together in the making of the film — all of that should be in the film. This is the way I try to let a film grow, itself, just by letting everything in. You get in a zone that relates to the story you’re going to tell. You keep reminding people what that story is, but you don’t get in the way of them bringing their personal ear to that, or their personal heart. It should be, “When Sean tells the story, what does it say to me? What does it remind me of?” That’s where film becomes most worthwhile, and valuable.

Is art elevated when it’s personalized, as opposed to so many dismissible movies that are high concept?

Penn: I wouldn’t just say high concept. As soon as people are making things out of… applying itself to a current ear, or eye, whether that’s cinematic or not; things that are trendy. People will perceive like sheep, but they will not feel like sheep. So what happens is that what’s personal is something that takes in all of the feelings that support that story, that the director recognizes. That can be in a very indirect way. For example, it’s in the way you cast somebody. You say, “I don’t know why he is the person as I read it, when I wrote it. But he is. And now, I’ve got to trust that. I don’t know why it is that when I imagined going to Alaska with a cinematographer, this guy sitting across the table from me, Eric Gautier, feels right. He feels part of the family of this thing.” So you’re casting a family of like-mindedness and like-heartedness, and that’s what makes a thing personal. Your talent, or your craft, or what you have to say is in your choices. The way you live your life is in your choices, and that’s the same way you tell a story. It’s in your choices, and therefore, not everything is direct.

The book reveals that Chris’ anger toward his parents was rooted in his discovery that his father had a secret relationship with his ex-wife. Why didn’t you use this as a major plot point?

Penn: Well, Jon Krakauer would disagree with your notion that I didn’t. So I think I did. But there’s a lot more to it. What’s insinuated [in the book] is systemic deception that creates a life where, once revealed, a table isn’t a table anymore. So if you have sanity, and you find that all the things that have been presented to you, the world around you and the personalities around you or the emotions around you, suddenly reveal themselves to be false, you have to find a place for your truth to be. You have to dismiss the frauds that have been presented to you.

Emile, you’ve played fact-based figures in Jay Adams in Lords of Dogtown, with a character based on Jesse James Hollywood in Alpha Dog, and now McCandless in Into the Wild. What is a movie’s obligation to the truth?

Hirsch: That’s tricky terrain. It’s whatever you decide it is, whatever responsibility the filmmakers and the actors put into it. I don’t think there’s any master rule: “You have to depict it in this way, for this reason.” For example, on Alpha Dog, I didn’t really feel any type of responsibility to depict Jesse James Hollywood as he was. The character was named Johnny Truelove. Whereas, in portraying Chris McCandless, the responsibility just felt greater. Part of it was rooted in the admiration for the character, and the melancholy I felt for Chris and what happened to him and his family. There was something different in the canvas that just increased the feeling of responsibility that I had. I don’t know if there’s an overriding rule I would follow for characters based on real people. I don’t know that there really is one. But on this, definitely I felt responsibility.

Sean, you stuck very closely to the spirit of that book. Would you have taken dramatic license, or did you, to make a more compelling film?

Penn: Listen, I know the nature of what you’re doing, and so I’d ask the question the same way, but that doesn’t prepare me to answer it as asked. “Dramatic license” is just a label that I’m not going to apply to my thinking. I would start by answering the question you asked Emile. My answer would be, “Intend heart, intend no harm and say all that you need to say.”

Emile, you considered how hard this job was going to be when you accepted it; how close were your expectations to the realities of a difficult role?

Hirsch: You can know in your mind that it’ll be a challenge, and that it will take a lot of commitment, but no matter how you envision it, in playing the part, the reality is much different. The highs are so much higher, the lows so much lower, when you’re in the present moment. You can prepare in your head, but you don’t feel what it’s like to climb a hill when you’re sitting in your apartment.

Sean, how close did Emile come to pulling off what you had in your head when you cast him?

Penn: I really don’t think this film could have been made without Emile. I might not have known that while I was writing it, or preparing to do it, or when I was going for financing. It’s a combination of things: the depth of the performance, and on top of that, when we were on location, there’s a directorial side to what Emile was talking about, in what the anticipations are. I find so much exhilaration in directing films that it never occurred to me to be concerned for how difficult or challenging my job was going to be. But certainly it occurred to me how challenging whoever played that part’s job was going be. I was not able to foresee what a challenge it would be.

When I was watching it, and having acted in plenty of movies myself, I could not imagine being in his shoes. It was so far beyond the usual challenge. You look at these things like scenes, no matter how many movies you make. You never look at it from the standpoint of fifteen hours with the snow up to your tits when you’re directing, and you know what the next moment’s going to be, or at least you know you’re driving the car. But someone else is in the passenger seat, and every now and then you’ve got the camera set. He doesn’t know how long the drive is going to be, and then you ask him, “Climb out on the hood and stand there while I drive through this storm, and I’ll let you know when I’ve got the shot.” So watching him on the hood of that car, I realized, my gosh, I hadn’t seen an actor commit himself to the work process, in this way, ever before. So I feel very, very grateful for that, and for the heart and talent that he brought to it. With this particular character, you wanted to cast somebody that you could photograph as he goes from boy to man. I felt that occurred here, and that brings so much to it as well. The most challenging part of that was capturing the emotional difference between a boy and a man.

How did you do that?

Penn: I find that the way to draw imperfect characters is to draw real characters, then let them have their moments in things that might not always be sympathetic, and might not always be the most charming choice. Yet what happens to most writers and directors is, you have actors that come in and decide to charm it up. They’re not ready to be real in that time, in that character’s life, warts and all. There’s a kind of subtle genius in how [Emile’s] talent breaks through, in that way. [He’s] representing his own generation, and it really is, cumulatively, what makes the movie work.

As you filmed him in the outdoors, was there ever a moment you felt maybe that you’d pushed him too far?

Penn: No, I’d never be capable of feeling that, in this game. [Except] I most certainly was nervous when he was with the bear. But in terms of emotional territories, that kind of stuff, you get your SAG card, and then you’d better come to play. That part of it I expect.

Emile, with the bear, or at any other time, did you waver a little?

Hirsch: There were maybe moments where I got concerned, but there were never really any roadblocks.

Just another obstacle, [and] I would figure out how to do it, so that I could get around that. It was all about figuring out how to tackle each problem and then move on to the next one. I never felt like it was something that could stop me, or not let me continue. If you’re climbing a hill with a lot of rocks on it, if there is a hard part to get up, you don’t just stop and turn around. You look at the rocks all around you and figure out the best angle up the hill.

As you were doing all this stuff alone in the wild, and feeling hungry as you lost all this weight, how did your relationship with your director, who is also a gifted actor, help keep you on point?

Hirsch: Sean’s experience as an actor was something that really helped me along. I felt like he understood what I was going through, maybe a lot more than someone would have who didn’t have experience in front of the camera.

That was very inspiring for me, and helped drive me in all kinds of ways.

After playing a man who pushed his physical and mental capacities to their limits, what did losing forty-one pounds and immersing yourself in this role teach you about your own resolve and strength?

Hirsch: The main thing is simple, I suppose. What you’re able to achieve when you set your mind to something like this is far greater than what you originally conceived. Most of the stuff I was able to do in the film, I absolutely didn’t know beforehand that I would be able to achieve. I hoped I could, but I didn’t know. It harkened back to what Chris McCandless viewed as a worthy challenge. To him, the challenge where the outcome was certain wasn’t really a challenge at all. I relate to that a little. The film was the kind of challenge where the outcome was definitely not certain. And I’m thankful that it was like that, because it was a real challenge and not a phony challenge.

Sean, if a breakout young actor like Emile was trying to have a career like yours, how would you guide them as they make hard choices that will determine if they’re a flavor of the moment, or long lasting?

Penn: I’d say invest as little in careerism as possible. Provide yourself the opportunity to express as you live, to be able to identify those things you want to express as your own life reveals them to you.

At what point in your career did you come to that realization?

Penn: I feel like these are things we don’t necessarily come to realize — well, you do realize it, but your realization is that it was always there. What happens is, you start out in an uncomfortable pursuit of clarity. Then, bit by bit, the clearer you get, you start to own it. Once you say, “OK, this is why this didn’t feel right, and this is why this did feel right, to do. And now I know what the difference is between those things. I know what I need to pursue that is shared with the one that did feel right to do, that only alters as my life becomes more informed.”

Was there a film where it became indelibly clear what you should do?

Penn: Yeah, there was a moment I felt that was the right thing to do, and the worst thing, at the same time. I was in the middle of doing great writing, as an actor. I was in the middle of doing David Rabe’s Hurlyburly. I do believe David Rabe is the greatest living American dramatist, and I’m not prone to say things like “greatest” about writers, but I do say it about David. David was directing it, on the stage, and it was fulfilling all the dreams of revealing a bit of character at a time, exploring it in the rehearsal period and being part of sharing human drama, which is what you want onstage or screen, in your lifestyle. And it occurred to me, [after] I had that ideal experience, that part of it was fucking awful. [The part of] being the actor. That really pushed me. I wrote my first screenplay in two months after I finished that play.

What part of acting was awful?

Penn: Once I saw [that I was sitting in the seat right next to the seat I wanted to be in], it wasn’t so much that I loathed acting. You loathe anything that holds you back from the thing you love most. But I got into [making movies] to break the tape. I don’t want to just sit there closely and look at it.

Denzel Washington and Mel Gibson both had to act in their early directing efforts in order to get financing. How have you avoided that? How much of an issue was it as you tried to get financing for Into the Wild?

Penn: Well, I don’t know that those guys had to act; I wasn’t in on those financing meetings. It may well be that they wanted to, or may well be that they’re comfortable doing both at the same time. In my case, if you’re with the woman of your dreams, then ideally, in my view, there would be no reason to be with someone else, also. So I’m with the woman of my dreams, in the director’s seat. Or I’d have no reason to be in it.

So you weren’t presented with scenarios from financiers like Denzel was, where you asked, “OK, you’ll give me how much if I act in it, and how much if I don’t?”

Penn: Certainly it wasn’t a discussion on this film. It has come up in other situations, but I’ve developed everything; I’ve never gone and done something that somebody came and offered me. I’ve only done things I’ve developed, and I developed them with the intention of only directing them. I developed or wrote them from scratch, and what I tend to do is cast the pictures before I go to the money. Because then, they don’t feel like they have to talk about actors to you.

Emile, you’ll join Sean onscreen in the Gus Van Sant-directed Harvey Milk. How did that come about?

Hirsch: Gus had given me a call, wanted to get together. [It’s] a wonderful script, [inspired by] an amazing documentary, The Times of Harvey Milk. Not a hard decision.

Sean, how did you feel about a re-team?

Penn: Gus told me about it and I said, “You gotta be fucking kidding, I spent the last two years with that guy. I don’t need any more of that shit.” No. It was fantastic. Because I have such regard for Gus, he’s called me at certain times about actors, bounced stuff off me. But I never was considering who to tell was good for any parts here. So I just got a happy surprise. I thought, “This is terrific and it will be interesting.” This movie, Into the Wild, was such a particular thing, and Emile came to it at a particular time in his life. He was a very mature young man those several years ago, and he’s made gigantic leaps. But I did look at him as a younger man, then, and the experiences that we’ve been through have led us to become as much colleagues in our personal lives as in our work life now. [We’re on] much more equal footing. So I look forward to spending time with him, as just a couple of fellas, and not that older director and that kid just about to come into his own.

![]() ulian, you’ve said your father’s passing influenced The Diving Bell and the Butterfly. How much did your own grief inform what we saw onscreen, and how many of the scenes between Mathieu and Max von Sydow, who plays his father in the film, were based on your interaction with your own father?

ulian, you’ve said your father’s passing influenced The Diving Bell and the Butterfly. How much did your own grief inform what we saw onscreen, and how many of the scenes between Mathieu and Max von Sydow, who plays his father in the film, were based on your interaction with your own father?

Schnabel: It would be more interesting to let Mathieu answer, and I’ll react. I told Mathieu certain things about that relationship.

Amalric: It was the end of the shooting; we did all of the flashbacks after the hospital scenes. I remember Julian giving Max von Sydow his shirt. You could feel thi ngs. Julian fell upon this book at a time when his father was ailing, and as his son, he couldn’t help him not to be afraid of death. That was something Julian told me the first time we met. I remember that shirt distinctly, and that scene.

Schnabel: I’d seen Mathieu’s work, so when [producer] Kathleen Kennedy came home from [making Steven Spielberg’s 2005 film] Munich saying she’d met this French actor who’d be perfect, and she mentioned his name, I said yes in one second. Mathieu came to New York two Thanksgivings ago, and we read the script together and talked about what it was. My father and I used to take a nap out in the kitchen, in the studio I built out in the backyard. So Mathieu and I were in that room. There’s a picture of my father, with his shirt off, and a friend of ours, with tattoos all over his arms, has his arms around my dad so it looks like my dad was in the circus and that he had four arms. Mathieu saw the picture of my dad, across from the kitchen where I used to take a nap with my father. Mathieu stayed with us for four days. My technique is about living with the actors, and becoming friends and knowing each other. I knew him, and I never asked him to audition.

Amalric: There was no screen test…

Schnabel: No audition, no rehearsal. I believed he understood the material, that I knew he would help me. In the same way he trusted me, I trusted him. I wanted it to be spontaneous. When he did the dialogue, I didn’t want to lose that connection to the character, particularly if people were talking to the camera. The sensation you get is, you don’t even realize there is a camera there. You feel like you’re talking to this man. You see the way he sees, you hear his thoughts, how he breathes and the sounds he’s hearing. What Mathieu did was, he was in a sound room where he could hear what people were saying, but they couldn’t hear what he was saying.

I told him, “Say whatever you want,” and had this faith. What happened with Mathieu and Max was, I gave [Max] my shirt. I used to shave my father. Mathieu and I became the same person, and Max was my father, and Max was his father. And Mathieu was his son. There was this exchange going on. The love that I felt for Max, and he felt for me, Mathieu also felt for him. There was a crazy energy going on. You can see, when Mathieu rubs his cheek and squeezes his nose, you don’t think these guys met for the first time, that very day, even though they had. Did you feel that at all, like they’d just met before doing the scene?

I told him, “Say whatever you want,” and had this faith. What happened with Mathieu and Max was, I gave [Max] my shirt. I used to shave my father. Mathieu and I became the same person, and Max was my father, and Max was his father. And Mathieu was his son. There was this exchange going on. The love that I felt for Max, and he felt for me, Mathieu also felt for him. There was a crazy energy going on. You can see, when Mathieu rubs his cheek and squeezes his nose, you don’t think these guys met for the first time, that very day, even though they had. Did you feel that at all, like they’d just met before doing the scene?

Amalric: No, I felt the familiarity of a long relationship.

Schnabel: People talk about Brando in The Godfather, when they stuck that cat on his lap. It looked like he’d had that cat forever. He didn’t make a big deal out of it; it was on his lap. Then he throws the cat on the floor and keeps talking to the people in the room. Another actor would have taken that cat and made a big deal about it. It was brilliant, how he did that. Certain people can be so comfortable, they know they have to be in the present, and what Mathieu did with Max was so right. Mathieu is a very loving person, a good man. I never had an argument with him, and the only time I saw him pissed off was when he was in the diving bell and the man photographing him tried to pull him out of the water, because he thought Mathieu was freaking out in there. When they got Mathieu on the land and took that helmet off, he yelled, “I’m acting!” If people are gangsters, it’s bad if they talk about trust, but for artists, it’s not a bad thing.

Mathieu, have you ever had a film, as an actor or as a director, be so informed by events in your own life?

Amalric: No, I don’t think so. As Julian said, it’s true that at one moment, I was trying to be Jean-Do, but I was also trying to be Julian, when I was on the set. Julian often needed to lie down on this little bed, or alone on the bed, to see what he wanted to look at through the camera. He was in that body, and there was a huge complicity. It was as if Julian and I were the same person, in another man’s life. It was like Julian and I never really met; we were this person.

Schnabel: French is not my first language, and if I couldn’t figure out how to say something to the kids, I’d ask Mathieu to say it. The fact that Mathieu’s a director also [helped]; he understood and modified some of the performances, just by his reaction to some of the people and what they did, whether he encouraged them, or he would comment in some way.

Can you give an example?

Schnabel: Where he goes to pick up his son, right before the accident. There was a whole different sequence in the script. Once you get to a physical place, a location, you know what has to happen, what the rhythm is, and it isn’t always what’s on the page. You see possibilities in your actors. This young boy, if he started to think too much, I thought we’d have a problem. My way of solving that was this: He knew my two sons came for home schooling while I was working. They signed up on a soccer team, and the guy said, “If you don’t shower, you don’t play.” They didn’t have any hair on their bodies, and were intimidated by other kids on the soccer team. They didn’t want to shower, and so they were thrown off the team. I got that to Mathieu right before he got in the car, literally two minutes before he got in the car, right, Mathieu?

Amalric: I’d say maybe thirty seconds before shooting. You ran to me and said, “This kid is thinking too much. Just tell them the story I told you about my two sons. Ask him if he’s got hair on his dick.” I said, “I can’t…OK, I’ll do it.” Julian will break professional habits that we all have, as technicians, as actors. He’d just take the best out of you. You are immediately looking at the world through a different point of view. I don’t know how he managed that, but it worked. On the beach, that scene with the kids could have been so stupid, so melodramatic. I remember again, with that little boy, he was trying to play sad and nice at the same time. It was the first time I saw Julian scream. You just yelled at him; I don’t remember what you said. Then the camera went on, and this kid was crying, and you just got this moment. We were supposed to shoot that scene in three days.

Schnabel: Four days.

Amalric: You did it in one day. Julian has the intuition that the emotion scenes have to be done almost like a casual moment. He knows that scene will be moving, but when actors try to be moving, that means they don’t have confidence in the situation or the director of the film.

Mathieu, you are about the same age as the character you played.

Amalric: I know, I’m forty-two, and very scared.

How do you think you would have reacted to that sudden imprisonment, compared to the way your character did?

Amalric: This film says, nobody knows how you are going to react. Nobody knows what we all have inside of us that we don’t use. What’s sleeping somewhere inside of us? You see what I mean? Who knows?

Schnabel: I learned a couple of things about this film, watching Mathieu become Jean-Do, who readjusted his life in the year and two months he had after his paralysis, to reconsider what he thought life was about. One was hearing Jean-Do’s best friend say that Jean-Do told him, “I am not the same person; I have been reborn as someone else.” I realized [Jean-Do] saw what happened as somehow positive, that he’d been selected. He grabbed on to the strangeness and the opportunity of writing the book. He was very excited about what he was doing — something that, if he wasn’t paralyzed, he couldn’t have done. He accepted his paralysis, in a sense, as a gift. That, I didn’t understand, because I just saw the claustrophobia in the beginning. I thought that was the worst thing that could happen to anybody, to be locked inside your own body. I used to think that when I would read to [close friend and former business partner of Andy Warhol] Fred Hughes. Then, Mathieu said something to me about how he felt, lying there. He had an eye patch over one eye, a bloodshot contact in the other, so he couldn’t see well through it, a piece of plastic in his nose, a bite plate in his mouth, [and] his lip glued to the side of his face. His hands were on pieces of foam so he didn’t move much. He said, “People treat you like you’re not there, and you become invisible.” I didn’t know this, but he made me think about what the disability was. Mathieu, I’m curious to know now, what happened to you while you were lying there and became invisible?

Amalric: First, I had this sensation of claustrophobia. Then, as people from the crew [and] everybody started to forget me, I had a big anger against humankind, for giving me that solitude. And after a moment, I really understood that sense of humor that Jean-Do had made it a great place to be. You’re invisible, you can watch everything, and your sensibility becomes extreme. It’s like you’re a peeping Tom. You have time to think, and realize things. We have so many problems we never think about, or we do until we have a good conversation. You couldn’t have any conversation here. I was thinking of Marcel Proust, on the bed at the end of his life, writing À la Recherché du Temps Perdu [Remembrance of Things Past]. He never left his bed. He was writing with the same thing Jean-Do had: imagination and memory. Jean-Do was living in a dream, and I really understood how sense of humor could be so natural.

Schnabel: There was no self-pity because he didn’t feel self-pity. He was involved in something that was extremely positive. People don’t understand. A woman who has MS, and works in a ward with other people of varying sickness, came up to me the other day. She said people who have strokes, or are crippled, have a sense of humor, too. They’re funny, and they communicate. We think because that person is sitting in a wheelchair that they never laugh, they’re stuck; we say, “Too bad.” They don’t think about that every moment of their lives. They get on with things. They’re thinking about what they’re going to build, who they love and myriad possibilities that we, as supposedly healthy, normal people, don’t even think about.

Amalric: Julian had this intuition that he could only do the film in the real hospital where this story happened. We were surrounded by people like that. Some would say, “I’m lucky, I can move my finger. The other guy can’t move his finger.” Another guy, who couldn’t move his legs since his birth, said to us, “I’m really lucky, because I can speak, and this other guy can’t.” There is no self-pity, none at all.

When Daniel Day-Lewis made My Left Foot, he carried himself as Christy Brown all through shooting, and it informed a spectacular performance. Mathieu, how much of your character did you carry around between takes, or when you weren’t shooting?

Amalric: Well, Julian shoots without rehearsing. The camera can go on at any moment. He needs the crew and everyone feeling ready to shoot at any moment. I tried as much as possible to stay still, on the bed, also to help the other actors. Those poor actors, in the first part of the film, when you don’t see Jean-Do, they were acting with the lens, with the camera. I tried to stay in character. But I’m also like Julian; I like pleasure. We had great meals, in the evenings; we had fun. I went and lost my money in the casinos. I have this in common with Julian: we don’t have this sense of seriousness, and we both believe that is the way to be real, because sometimes great seriousness can also be a form of prison.

Julian, maybe coming from the art world to film doesn’t shackle you to traditions and rigid structure. You didn’t rehearse, you encouraged improvisation. How do you think that approach lightened the sober and claustrophobic subject as a man trapped inside his own body?

Schnabel: I didn’t try to lighten the tone. The movie is pretty heavy, actually. But things that are serious can have a sense of humor. When you say the art world, I don’t really feel like I come from that, or that it’s art with a capital “A.” People talk about artists like it’s a big deal. Painters paint paintings. Hamburger-makers make hamburgers. What you try to do is not be too reverential, too impressed with the notion of Sturm und Drang, if you are making a movie about an artist. I’m sure someone else would have exercised [Jean-Do’s] fashion-world life more. If you look back at the movie, there’s one scene, which is quite short, but tells you a lot of information. He walks into [fashion designer] Azzedine Alaia’s atelier, which is huge, and you get to see Azzedine, you get to see the beautiful model, or more than one. There’s this photo shoot going on. He’s making a book so on the floor are photographs of these models who were very famous in the ’80s and ’90s, that actually went into his book. I tried to reconstruct what might be a possible day in Jean-Do’s life. It’s more about knowing your subject than trying to make something light. People make things heavy because they overinterpret what they’re trying to tell. You see that effort. It’s probably easier to shoot scenes that have more people in them than scenes where there are just two people talking in a room. The fact is, it’s like taking a bunch of stuff and tossing it into a popcorn maker. It heats up, and all these things start exploding. I feel like I was throwing different things in that room. A photographer doing one thing. Azzedine always had famous people around, so I [invited] Lenny Kravitz, and put a wig on him so you think you’re in the ’90s. Originally, that said he was in a photographer’s studio, but it evolves if you know your subject. The script is a guide. I’m sure there are scripts where the director has to illustrate every line, per what the producer and distributor wants. I believed when they sent it to me, that I was going to work on it and give it the Schnabel treatment. I don’t paint on a white canvas. I’ll find an old army tarp to paint on, a piece of material that has been touched by life already.

Why?

Schnabel: I like to commandeer the prior meaning and add another sense of use to them. Paintings are utilitarian, but if you get, say, an army tarp that covered a truck, you stretch it out, and you’ve got these burn marks from where the ropes were tied across. There are puckers. It has a sense of history to it. If I write something on top of that, in white paint, it looks like it could have been written on there because it had some kind of a use. You don’t know what the use was, but you get the sense of the intention.

Amalric: The script was like chords, and Julian improvised with those chords and it became jazz. But to improvise like that, you first need great chords. There were two or three chords that were in the right place. The fact we were in Jean-Do’s head at the beginning, the fact we don’t see the stroke until at the end, things like that. With that, Julian could really improvise.

Julian, how much resistance did you encounter when you decided to make the film in French, and why was that so important?

Schnabel: I thought, you’ve got the guy here, who’s French. The book is written in French, and this is a wonderful example of something that comes out of that culture, of this moment in time in Paris. The location of that hospital was so important. To abandon that would have taken some of the meaning out of the book, put you one step removed from the content. Why do you want to make a movie? Why not make it in English, in a soundstage in Los Angeles? Am I doing this for money, because I need a job? No, I’m doing it because I wanted to tell this story, as close to what I thought my imagination felt it was, and what it inspired for me. I could time travel in this; it just gave me such a wide palette, and I wanted it to be authentic. I went to that hospital, and everything was there. When Chris Walken played Vincenzo Coccotti in True Romance, he wanted to have human teeth as cuff links. I understand that. Maybe it’s a little different, but I couldn’t have made this movie in another place, and to hear these women speak the alphabet in French — it’s a huge difference from English. You don’t want your audience to be ignored. That was a huge worry of mine: hearing this alphabet, and how it became a kind of love chant, a sonorous, syrupy thing that everybody could dip into. There would be bigger box office if the movie was in English. They thought I was making it for a smaller audience [by doing] it in French. But it would have been an even smaller audience if I’d done it in English. Because it wouldn’t have been a good movie. We wouldn’t be talking right now. They wanted to make it in English originally, and it was a huge problem for me. Finally, after different meetings, and going to Cannes, all these meetings, finally I said, “Let’s either shake hands and do the movie, or move on.” I said, “It has to be in French.” After three days, while we were doing the casting, they said, “Fine, go ahead.” They saw how I related to the French people, and thought, “This guy is an American, but he could be a Parisian.”

Mathieu, we see a lot of European directors come to Hollywood to make films, but not many Americans who go make French films. As a French director yourself, do you think people could mistake Julian as a French director if they didn’t realize he grew up in Brooklyn?

Amalric: No. I don’t think a French director would have done a film like this. I don’t think he would have had the freedom, nor the enthusiastic eye. No. It would have been only realistic, but it wouldn’t have been another world, which was in Julian’s head. I’m not sure if Julian is American or European. He comes from Mars, you know?

Certain people respond better to structure. How did Mathieu take to the improvisation?

Schnabel: Most scenes, we did maybe one or two takes. When he was in that car, and he had that accident, I needed one take. I knew someone who had a cerebral hemorrhage and someone who’d had invasive surgery, and so I knew what it was like when someone is having a problem in their head. Basically I told him a couple of things about that, and he did this thing in the car that was absolutely perfect. I don’t know if good acting comes from good listening, but it’s amazing when you can say something to an actor, and they can use it immediately. Some people will ask you a million questions [about] who they’re supposed to be. This was pretty easy to work with Mathieu, and a great pleasure.

Mathieu, you’ve been in the business for twenty years, but how much did things change when you were discovered on the other side of the ocean for your performance in Munich? And as you prepare next to play the Bond villain, how important do you think it is for you to make Hollywood films?

Amalric: It’s funnier than that, in that I never thought I would be an actor. I discovered movies at seventeen, but I was attracted to directing. Between seventeen and thirty, I was on the other side of the camera. I was an AD, trainee, I did cooking, editing, everything. A guy named Arnaud Desplechin, with whom I did Kings and Queen and My Sex Life, [is] the guy that got the idea to put me on camera. In fact, I discovered that being on both sides was rich, because it helped as a director to learn what it was to act. Munich was like Cinderella. I don’t know what happened. But I never had a feeling like I was working with Hollywood people. Steven Spielberg is so free; he has no storyboards. He reacts to what happens, and I didn’t think about the fact he was huge. Same with Julian. [They’re] just filmmakers. Then, the Bond story has to do with childhood and dreams. It feels like a joke; I can’t believe it is happening. But it’s such a pleasure to go from a little French film without money [but] a great director, and then be in the Bond film. I don’t want to stop doing small French films, though. I love them. When you love movies, it’s not true that you only love Ingmar Bergman. You love also the Farrelly brothers, Wes Anderson or the Bourne films. I hate people who have principles that are limiting.

![]() n Youth Without Youth, Tim plays Dominic Matei, a man who fears he’ll never finish the book he’s spent his whole life writing. How much of the film was inspired by you not having made a movie in a decade, after trying so hard to make Megalopolis?

n Youth Without Youth, Tim plays Dominic Matei, a man who fears he’ll never finish the book he’s spent his whole life writing. How much of the film was inspired by you not having made a movie in a decade, after trying so hard to make Megalopolis?

Coppola: In the [Mircea] Eliade story, Dominic is an older man, maybe a little older than I am, and he’s totally alone. He’s ending a term as a professor, losing his memory, and he laments not only that he hasn’t finished his one great work, but that he has lost the love of his life — who, when he was a young man, he passed by. It really starts with the loneliness and the end of an elderly person. Obviously, I hitched a ride on that theme. I’d worked for years on my Megalopolis project, and was very frustrated with wanting to do a big personal film and not totally being able to lick the script, partly because of world events that happened. When you make a movie, you try to find your way into the story. This existed as a novella, and I followed the same form, but I thought, “This is an appropriate theme for me. I’d like to look at some of these things, and understand some of the questions that were in the Eliade story.”

You shot some footage for Megalopolis in New York, and then September 11 happened.

Coppola: Megalopolis was a movie about utopia, and it was set right in what I thought was the Rome of today, the world’s center, and that is New York. It was about a man and a group of creative people who say, “Well, why can’t we build the perfect society?” Right in the midst of this utopian reverie, so to speak, here is this terrible tragedy of the Twin Towers. Suddenly, New York couldn’t be the same in my story. No one would think of modern New York without thinking of this attack, of a world greatly changed, and issues of Islamic fundamentalism and security. Suddenly, all of this crept into this story about utopia. At first I thought, “Well, I can write my way through this, it’s an opportunity in disguise.” That proved to be a little daunting. Plus, the appetite for big movies that were not sequels of remakes was dawning. I didn’t really try, but it seemed so impossible to try to gain financing for a big-budget production that wasn’t a sequel. I just felt like I didn’t know how to proceed.

How did the fixation on making the most of your time resonate with you, Francis, after spending a decade away?

Coppola: It was about eight years, but I was very busy. I was working on my script, building resorts around the world, which is another kind of creative activity. It wasn’t like that. I became frustrated in that I really love making movies, and really wanted to make a personal movie. I was hooked on making Megalopolis, and it became like being in love with a woman who doesn’t want you, in that you don’t have her, and you don’t meet other women either, because you’re so obsessed. I just had to take the step and say, “Megalopolis was a worthy thing, but I’d better unhitch myself from it, and go off and make another personal movie that I can finance myself and can control, and can get some actors.” With a big-budget movie, the first thing they ask is, “Will Brad Pitt be in it? Or will Leonardo [DiCaprio] be in it?” Whether it’s good casting or not. Those are both wonderful actors, but they can’t play every role.

Tim, how did Youth Without Youth‘s theme of time resonate with you, as you weigh your improving skills as an actor versus the fact you’re no longer on that hot-young-actor list that studios pay attention to because it mirrors the ages of the audiences that make opening weekends?

Roth: I remember at the very beginning [of my career], discussing this very thing with Gary Oldman. We decided there was a benefit to looking the way we do, which is these pasty-faced London boys. We don’t sit on those lists, and therefore can have a longer career. Because if you really are on those beauty-driven lists, whether or not you are a fine actor, and many of those people are, you’re always looking over your shoulder for the next ones that are coming up.

Coppola: Also, you have to look at the fact that that list has grown very short. It’s three people now. Realistically, there are three people, maybe four, on that list.

Tim, you wrote letters to Francis when you were an unknown actor, telling him you were available if he ever needed a Brit. When you discovered that he was returning to direct after a decade-long absence, and that he had written a script and wanted you as the star, in every scene of the movie, what was your reaction?

Roth: Panic. It was something that Francis sent me, and it was something so fully realized. It threw me into a panic, but it also came at a time when I was feeling the opposite of how Francis felt, when he was ready to launch himself back in. I was ready to fade out.

Roth: Acting was becoming something that was increasingly… I was becoming bored with. Bored with the kind of characters I was playing; the repetition. When Francis came along with this, it was something very, very different. And it made me incredibly nervous. Initially, I was wary. I didn’t know if I could live up to the task.

Now that you’ve come through it, what has Youth Without Youth done to your appetite for acting and directing?

Roth: It really did turn me around. It whetted my appetite for acting again. Very much so. Everything Francis was discussing early on, down to the actors we used as reference points, like Alec Guinness, it’s everything that an actor really wants to hear.

What movies were reference points?

Roth: We talked about Goodbye, Mr. Chips quite a bit, didn’t we Francis?

Coppola: There is a term we throw around, which is “personal cinema” and “personal filmmaking,” and really, there’s no mystery to that. It’s when you make films about things you want to learn about as a person, or that you want to understand better, or that you connect with. Rather than, “Oh, here’s a project, and it could be a success. What’s it about? Oh, it’s set in the 1900s.” It seems like filmmaking has become so distanced from the actual directors and actors doing it. When I was a young man, I was seeing films coming out of Europe, Japan [and] Sweden that seemed very personal to the filmmakers. I felt that’s what I wanted to do. It was an adventure. You mentioned at first that you enjoyed this film, but you weren’t sure you understood all of it. That’s partly because these are issues where there is no easy sum-up. What is the difference between reality and dreams, and what is the human consciousness like, and what is time? Of course, you can’t understand it entirely. But it’s fun to think about it.

Roth: I remember asking Francis, very early on, “How are you going to do this? How do you film this?” And he said, “I don’t know. That’s the journey, that’s the adventure, to try and find a way of expressing these notions through film.” I don’t know if it’s the first time it has been done, but it is the first time I’ve ever seen it.

One of the moments in Youth Without Youth that shakes you to the core is when Tim’s character speaks about the survival of the human race as a genetically mutated species after exposure to nuclear weapons. Some would point to ecosystem abuses, the demise of honeybees and the melting polar caps as a catalyst for our demise. What do you worry about most in the world, and see as the greatest threat?

Roth: I actually worry about the buildup of nuclear weaponry now; the soft nukes and whose hands they’re in, and the fact they exist at all. A new space race and cold war are terrifying things for all of us, apart from the fact that our planet is falling apart because of their actions.

It’s true; global warming and pollution and carbon in the atmosphere and horrible genocide, and a list of maladies. But no one says the real cause of that, and no one will say that word because when you say it, you come in conflict with very powerful institutions.

What’s the word, and what are the institutions?

Coppola: The word is “overpopulation.” When I was born, there were maybe 2.5 billion people on Earth. Today, we’re approaching 7 billion. And we still operate with religions that prohibit contraception, and with political people who make life, which is sacred, they make it sacred even beyond as it was given to us by nature. And businesses. They are talking about making cars that will be sold for $3,000 apiece. So ultimately, there are too many people on this earth and none of our really powerful institutions understand that population growth is what is causing all of these other problems.

Several of the stars in Youth Without Youth are best known for the Oliver Hirschbiegel film Downfall, about the last days of Hitler. Based on the way his first American movie, The Invasion, turned out, it appears Oliver got kidnapped by Hollywood and put into a remake that failed and had none of that original voice Downfall had. A lot of outsiders experience that. Why does the Hollywood studio system tend to ruin artists who come here from abroad?

Coppola: In the ’70s, which is talked about as a nice period of filmmaking, it was the most impressive, even businesswise-earning pictures. And they were all one-shot movies. They weren’t sequels, weren’t based on a remake. Yet in the late ’90s, if you looked at films that were comparatively as successful, they were all remakes or sequels. Clearly, something has happened in the ownership of what you call the studio system. The “M” doesn’t stand for movies; it stands for money, because they are all subsidiaries of larger groups that are owned by what are now the studio heads. But they are not studio heads anymore. They are communication corporation tycoons. They still believe in risk, but it’s not the risk of making a stunning movie for the first time. The risk is to buy a new telecom company, or to buy a satellite. [In] the era before the ’70s, there were still showman owners who may have been vulgar and moneymen, [but] there were people like Sam Goldwyn, who still loved the idea of coming out with The Best Year of Our Lives. There was Darryl Zanuck. Today the real bosses are way up in the hierarchy, and the play they’re interested in making has nothing to do with making new, interesting or original movies.

This interview is being done days before the start of the Writers Guild strike. Like you say, it’s all about money. What has to change within the studio system for real artists to emerge again?

Coppola: You speak of the studio system as if it’s organized religion. There isn’t a system. There isn’t a studio system anymore, there’s a business known as the film business, which is oriented toward very high-grossing pictures that are hopefully profitable. That’s basically what they’re doing. I understand in this climate that you can’t even make a drama anymore, but I don’t really know because I haven’t been part of that for so many years. I want to be an independent poet, and just be Don Quixote. Fortunately, I made a fortune in the wine business, so I can afford, on a certain level, to finance my own pictures.

Roth: You’re in a very fortunate position, Francis. Because even the so-called independent filmmakers have been absorbed by the big corporations, of which there about six or so.

Coppola: They bought up all those independent distributors. Distribution is the key, and it’s controlled by the same people who control the other kind of movies. So, yes, they’re looking for young filmmakers that will make movies like Little Miss Sunshine, but that can then be promoted into big pictures.

Roth: It has become the farm team for those other movies.

Coppola: Yes, but there’s nothing wrong with that system. The question is, can other artists be independent, be dashing and daring, and not be afraid that, “Oh, my God, he was ambitious!” Like it’s a terrible crime to try and be a little ambitious about the material. But it seems to me that that’s a wonderful thing, whether you’re an actor who’s going to struggle through a character that’s a little bit at the edge of your ability, and the audience gets the thrill of seeing you do your work. There’s that beautiful phrase that I always get wrong, but it’s [along the lines of] “If your grasp doesn’t exceed your reach, then what’s a heaven for?”

Francis, does directing that kind of studio blockbuster have any appeal at all to you, at this point in your career?

Coppola: Well, in my younger age, I did like new challenges to make films I hadn’t made before, but at this point, I don’t have any more economic need to work. I want to spend time developing things that interest me. That is my knowledge, and my understanding of the cinema as a wonderful field. And I still want to learn.

Francis, you were widely quoted as implying that big bucks get in the way of the artistry of peers like De Niro, Pacino, Nicholson and Scorsese. What kind of grief did they give you?

Coppola: I very much appreciate you mentioning that. Do you know the Daily News and a column called “Rush & Molloy”? That story was totally manufactured and untrue. Some comments I made, which were not pejorative at all, and which were funny, and which I would happily say in front of Jack, Al and Bobby, were totally wrapped up in a headline of “Francis attacks these actors.” It was totally untrue, and I have nothing but admiration for those guys. Certainly, Bobby is anything but lazy, and he labored on a beautiful film, The Good Shepherd, for other than financial reasons. Jack is a phenomenon of his own, a great prankster, and Al is a dear friend. That was so heartbreaking, to see that trashy gossip story that got repeated. So thank you for asking me. One of the things about news today is, it pops up on hundreds of different outlets and suddenly people think it’s true. That wasn’t true.

More artists are trying to own pieces of their films. You’ve done this for years, Francis, and put yourself at great personal risk on a few occasions. What is the real benefit? Is there one that made you unbelievably wealthy, compared to taking a big gross-dollar paycheck?

Coppola: I’d say Apocalypse Now. In its time, it was considered an expensive picture. I did the guarantee of the finances for it, and when it came out it was damned by many critics. And it just didn’t go away. People wanted to see it. Slowly, for better or worse, it became a movie people still look at today. When you make a movie that’s viewed by people for thirty years, it becomes a very valuable possession.

Would you say you’ve made 100 times what you’d have made if you’d gotten that film financed, and you just took a salary and maybe a gross payday?

Coppola: I don’t really think of it that way. I couldn’t even begin to answer that. All I can say is, I own Apocalypse Now, and if I wanted to, I could burn the negative and say, “It’s never going to be seen again.” That’s ownership. Every time they announce a new technology, like HD or Blu-Ray DVDs, the first thing they run out and buy is a copy of Apocalypse Now because they know it looks and sounds good. It’s achieved that kind of standing. The Godfather has as well, in a different way. Basically, you want to make movies that aren’t in and out of theatres in three-and-one-half weeks, but rather can live for decades, if possible. That’s the goal of anyone wanting to be an artist.

Francis, people regard the period of The Godfather, The Conversation, The Godfather Part II and Apocalypse Now as your creative zenith. When watching Youth Without Youth, one can’t help but think of how your own hard miles informed this character: the idea of personal loss, career setbacks. Could you have made this movie back in the 1970s, and how much of a benefit is personal experience to a filmmaker?

Coppola: Of course, when you are making a film, you’re using your whole life. I know because this story is about what it is, and Tim is playing a person vaguely, at least when he starts, my age, and is at the end of a career. But let’s face it: I’ve had a spectacular life. I’ve had tremendous success in the film business. Sure, I lost a fortune, but I made it back four years later, and it was three times more than I had. I’ve gotten to see my children go on and make films, in my footsteps. I’ve been married to the same woman for forty-five years. I’ve made a great fortune in other businesses, like the wine business. So, please, I’m not a guy to feel sorry for. I’m a man who has enjoyed success in every area I went to. And arguably made some memorable films. But I’ve found this in Europe, and I was onstage in Turkey recently, where they had played The Godfather theme, and they are showing helicopters, and I said to the audience, “I know you love The Godfather, and I thank you for that. And I know you were excited by Apocalypse Now, and although at first that picture was viewed with a squinting eye, I thank you for that. But I beg your permission to go on, and not make more Godfathers, and not try to make [more] Apocalypse Nows. I beg you to let me go on, and look into things I’m interested in, now. I don’t care whether you think this one is as good or bad as the other films.

There are themes of regret and loss in this film, as Tim’s character gets a chance to relive his youth, and address missed opportunities. For both of you, is there anything you’d like to go back and have another shot at?

Coppola: Well, in this movie, he gets to go back and fall in love again with the woman he lost. What a thrill that is. If I was to get hit by lightning and made young, I’d like to go back to three weeks before One From the Heart started, when all my team came to me and said, “But we can’t make it as live cinema with sixteen cameras because we can’t light it as beautifully.” I wish I’d said, “Fellas, we’re making it as live cinema. We’re not shooting it one shot at a time. Either come on this adventure with me, or leave.” They were my friends, and so I didn’t say that. But ultimately, the only thing in my life that I regret professionally is that when One From the Heart came down to it, it was planned for, the reason we built Las Vegas in the studio, the reason we built this electronic booth called the Silverfish, was so that we could shoot it live, with multiple cameras. It would have been finished weeks after we shot it. In one act of cowardice, I let my good friends talk me out of it, and I would like a chance to go back and do it again.

Tim, what about you? Is there something you might have done differently?

Roth: It goes back to when I had to make a decision on whether to be a painter and a sculptor, or whether to pursue acting. I’d like to find out what would have happened had I gone down the other road, if I’d taken painting and sculpting and gone through with that. That would be interesting.

Tim, you are just starting out as a director, but do you aspire to get to the point where a movie becomes such a personal statement?

Roth: Film should be a personal passion, and the films I want to make are very personal. I start with a love affair with the material. Any attempt to direct a film is going to take a much larger chunk of time than anything I’m going to act in. So it has to be a love affair, a completely passionate journey.

Does your protagonist become a symbol of you, the filmmaker? John Woo saw his fantasy self in Chow Yun-Fat, for instance.

Roth: I don’t have that affliction. The material I’m looking at as a director right now, I don’t see myself as any of those characters. There are other reasons for making them.

Francis, aside from Dominic Matei, which of your protagonists, from the Corleones to Capt. Willard or even Kurtz from Apocalypse Now, did you see as extensions of yourself?

Coppola: From the beginning of my career, when I made The Godfather, the popular view was, “Aren’t you Michael Corleone?” “Aren’t you this Machiavellian guy who’s manipulating people?” Then, on Apocalypse, it was, “Well aren’t you a megalomaniac like Kurtz? Aren’t you out of control like that?” When I made Tucker, it was, “Aren’t you this wacky American entrepreneur, taking on the studios?” Bottom line, yes. In all my movies I find something of myself in them, which is my approach. I look for something of myself that I can latch on to. And when you see a great performance, like Gene Hackman or Bobby Duvall, don’t you always see mannerisms of Gene Hackman or Bobby in every character? I know them backwards. Writers, filmmakers and actors are manufacturing this out of themselves.

Roth: Francis, do you go in search of that? When I’m thinking of things to direct, I’m not looking to mirror myself.

Coppola: I don’t go in search for that at all, but something makes me say, “Yeah, I’d like to do that.”

Tim, when you think of the ’70s auteur heyday that Francis was part of, do you feel like you missed out on something special, a freedom that doesn’t exists because of conglomerates and high production and marketing costs?

Roth: I got a little taste of it.

Coppola: We spent the last year making a ’70s movie.

Francis, as a central figure of that movement, how close was it to being as good as our romanticized perception of it?

Coppola: It is romanticized. It was tough. It’s always tough to make movies, and more personal movies, and to reconcile commercial films with more artistic films. That’s one thing those films were known for. Bonnie and Clyde, which started that trend, was damned by the critics when it first came out. Then they recanted. The studio didn’t want to release it. The Godfather was extremely unpopular at the studio while I was making it. Apocalypse was widely heralded as the biggest failure of Hollywood filmmaking of the last forty years, at one point. These are recent memories. People say to me, “Gee, you made The Godfather, The Conversation, Apocalypse Now and The Godfather II in four years, one after another; how did you feel?” Well, I was very frustrated and depressed because ultimately, many of those films were very harshly criticized. Go back and read the reviews on those films. Who won the Academy Award when Apocalypse Now came out? Do you remember? I’m sure it was a film that got a good review in the trade press. It was Kramer Vs. Kramer.

Well, that was a memorable film, also.

Coppola: There were many wonderful films, good actors and stuff. In the film business, there is fear about films being unusual. For heaven’s sake, I got fired for writing the script of Patton. The opening scene of Patton got me fired because they thought it was so out of logic and inappropriate. What does it mean? The things that get you damned and fired when you are young are the same things that give you lifetime achievement awards when you’re old.