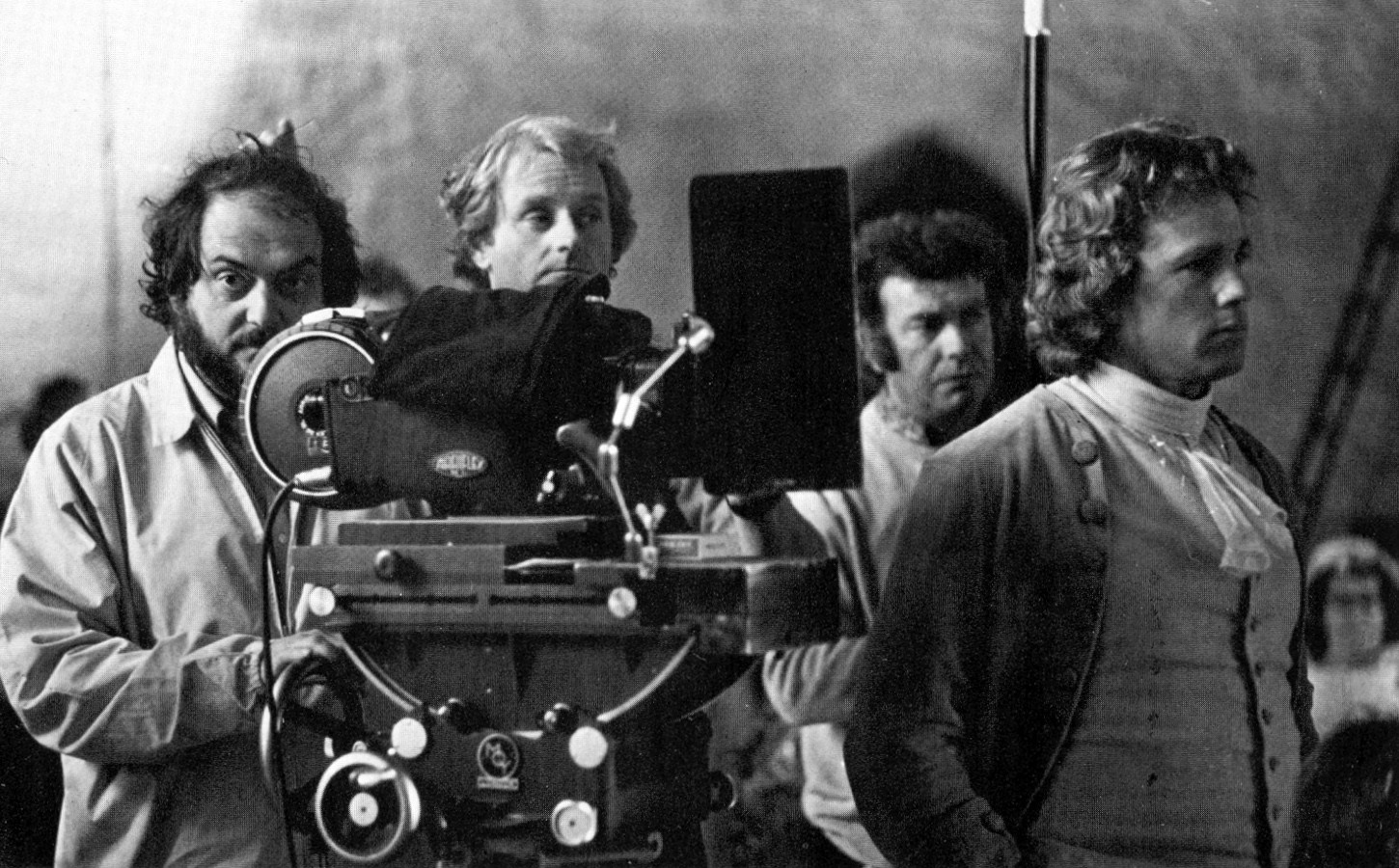

I acted in two of his films — Barry Lyndon and Eyes Wide Shut — and also worked as his assistant. My work across the board covered everything from casting to coaching actors; from layouts to lab work; from marketing to video transfers, and more.When Fade In asked me if I’d like to contribute something to the issue, I thought it would be nice to do something a little different — i.e. talk about two scenes from each of his films that mean something to me. Some of the scenes from his early films I wasn’t conscious of until I saw them either in my teens, or even later, when I was at drama school, as his films were released. For the last four of his films, I was there with him — as mentioned, either as an actor (Barry Lyndon), his assistant (Full Metal Jacket, The Shining) or as both actor and assistant (Eyes Wide Shut).This isn’t a class about scene construction, writing or acting — it isn’t a “Stanley told me this” or “Stanley told me that” — though when we worked together on these films, for a myriad of reasons, we would talk about them. This is about the emotional connection I made with them — whether I was in the scenes or not — when I first saw his films and wondered, all these years later, why they were so special to me.And I’m going to start right at the beginning, which for Stanley, was…

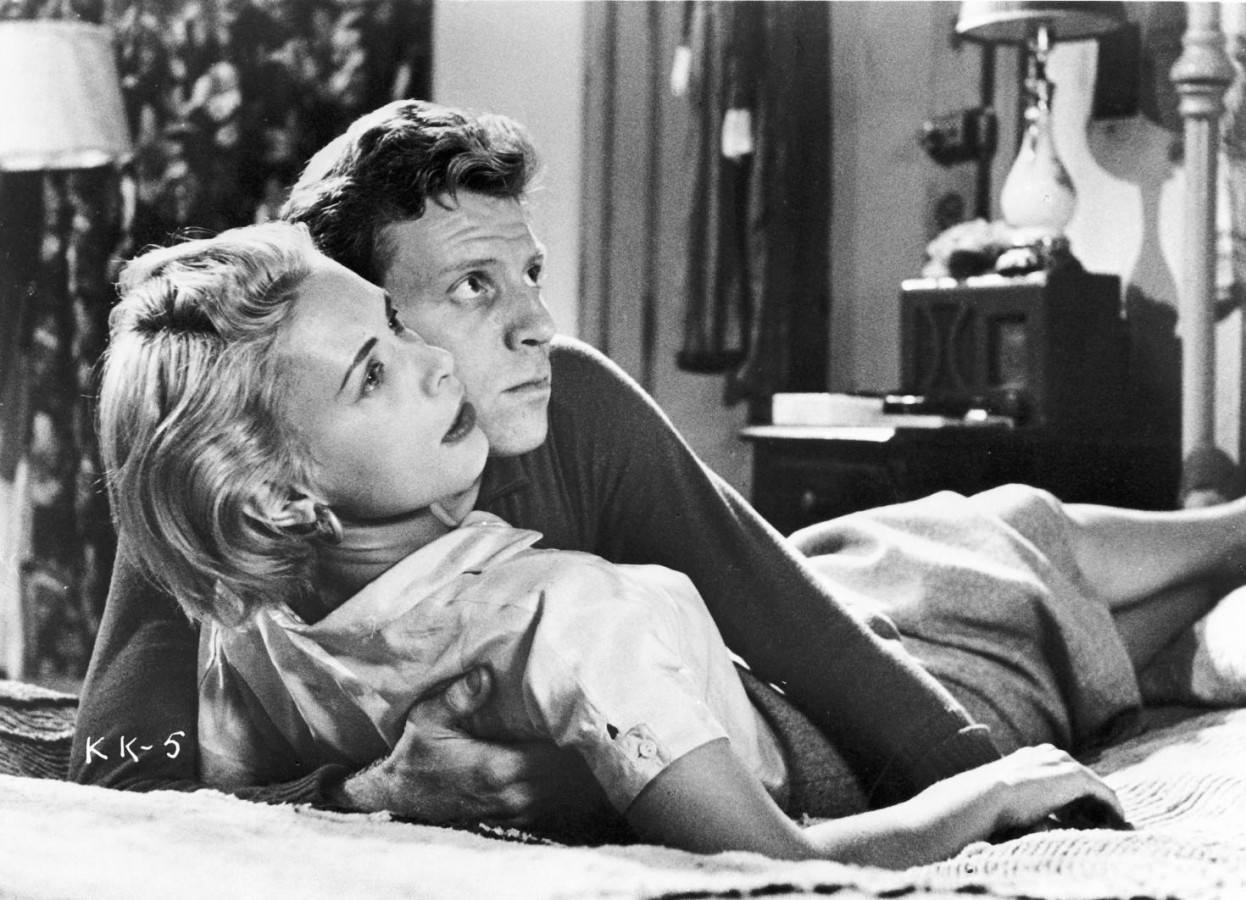

KILLER’S KISS (a.k.a KISS ME, KILLME)

I first saw this film when I was a drama student in London, at an art-house cinema in Hampstead. I was twenty at the time.What a great title for a so-called film noir, huh? The title itself is full of carnality, betrayal and revenge. That was always what film noir was basically about.The story concerns a boxer, not a bad one, but he has a basic weakness — what they call “a glass jaw.” His name is Davey. He lives in New York, but when I saw the film for the first time, it was no New York I had ever really seen in a film. It was dull, gray and desolate and Davey doesn’t really seem to have any chance of salvation until he meets Irene — the girl in an apartment across a narrow alleyway he’s been unavoidably watching from his window. They do meet, and there’s a mutual spark of attraction. It’s noticed by a scumbag dance hall owner named Rapallo, He fancies Irene, one of the dancers who works at his hall.But Davey is there for her, and when Rapallo understands this, he kidnaps Irene.

SCENE ONE: When Davey goes to meet Irene, who’s on her way to pick up her final paycheck from Rapallo at the hall, he’s waylaid by a couple of street performers who run off with his scarf. He chases them, thus missing his appointment with her.Throughout the sequence, I saw a New York that I hadn’t ever seen in movies before. The scene, for me, was full of life and vigor — bright lights, window displays of toy clockwork fish and people, people, people.

The streets were not the sun-drenched, hot and sweaty New York streets I’d seen in other movies. They certainly didn’t resemble the streets of London, where I had lived. It felt like an exciting, dangerous place, and it made me want to be standing in the middle of it all, watching this dance of life for real.

SCENE TWO: The chase through the streets and over the rooftops as Davey tries to escape Rapallo and his thugs.

Davey is on the run from Rapallo and his thugs in the early dawn — side streets marked by deserted warehouses, fire escapes and flat rooftops with skyline views of Lower Manhattan. It’s a cold, desolate place and shot in that gray, chilly light of early morning with the running figure of Davey desperately fleeing three men who need to kill him. The excitement and the thrill of seeing this more than familiar action set in a milieu so totally unfamiliar to me gave me the sense that this was something new.

In other words, in these two scenes, inside a film that really is a simple story told many times before, Stanley had created a different and new experience for me.

THE KILLING

The film Stanley always regarded as his breakthrough, it’s about a planned robbery of a race-track betting office by a gang of ne’er-do-wells looking for a way to get “the good life.” The robbery would be carried out the instant the heavily backed favorite is shot dead as it’s coming around the home bend. The tale is told in a unique way. Each of the main characters is shown on the day of the deed starting from the same time point, 8:45 a.m. That was enough to grab my interest when I saw it on television in England as a young teenager. And no, at the time, I didn’t have a clue who had made it.

The two scenes that really connected with me then, as now, in fact, are:

SCENE ONE: The members of the gang, led by Johnny Clay (Sterling Hayden) sit around the table to plan every single detail of how they will pull off the heist.

Johnny is masterly — all fast-talking confidence, convinced that, if planned properly and with everybody fulfilling his part in the robbery to the second (including a wrestler he will employ needing to start a fight in the betting hall that has to start at 4:00 p.m. and last long enough to distract every cop on duty so Johnny can get to the back room where the track’s money is stashed), there is no way anything can go wrong. He is so authoritative, I remember thinking at the time that it was bound to go wrong. But that wasn’t, (and still isn’t) what moved me. Somehow, I had an empathy with these marginalized people. They are, of course, pinning all their hopes on their scheme working out. They’re like children who know that what they are planning is wrong, but the risk is worth taking. They’ll all be worthy members of the human race when it’s done.

Which leads me, naturally to…

SCENE TWO: When Johnny and his girlfriend, Fay, are the airport to check in his suitcase stuffed with money, trying to take it on board as “personal luggage,” He is told that he cannot do so.

As he argues his point, you not only see, but feel, the blind panic as he realizes he has no alternative but to do so. Kubrick plays this scene in one shot. Johnny knows deep down that the game is up — so much has gone wrong — and so do we. And when I saw this film for the first time, my mind instantly went from him realizing everything had gone wrong — from the moment the heist had been successfully carried as he mentally waved goodbye to the suitcase now on the conveyer belt for loading onto the plane he and Fay were trying to escape on — straight back to that scene where he and his fellow gang members (all now dead, incidentally) sat around that table, with Johnny, all “perfect planning,” the “smart” one, the “leader” barking out his orders, his strategy, just showering his cohorts with his own confidence in the brilliance of his scheme.

I felt sorry for him. I bet I knew what he was thinking as he allowed the case full of money to go to the cargo hold of the plane he and Fay were trying to make their escape on: “This was the bit I probably should have planned better.” What he actually does say, as the FBI agents move in on him and Fay tries to get him to make a run for it, is, “What’s the difference?”

PATHS OF GLORY

Another case of the ill-conceived plan begetting horrific consequences! Set in World War I and starring Kirk Douglas (as Col. Dax), Adolphe Menjou (General Broulard) and George Macready (General Mireau), the film tells the story of a suicidal French attack on an impregnable German position. The results are far-reaching and inhuman.The first scene I marveled at was one of the first in the movie…

SCENE ONE: General Broulard’s arrival at the chateau.

The chateau is used as the GHQ by the French officers in charge of this division of French infantry. Its splendor is almost obscene when compared to what the infantryman in the trenches has to put up with. In fact, when Broulard (the avuncular but cunning commander-in-chief) arrives in General Mireau’s “office” the first thing he does is admire the furnishing and paintings, slipping in the flattering remark, “I wish I had your taste in carpets and pictures.” This, of course, is to soften the blow of what he’s about to tell Mireau to do. After the niceties are dispensed, Broulard broaches the subject: The High Command is ordering Mireau’s division to attack the German position (called the Anthill) no later than the day after tomorrow.Mireau wants nothing to do with it — his division was cut to pieces, the Germans have held the Anthill for a year and could hold onto it for another if they wanted to. Broulard says nothing at first. He gets up from the chair he sits in and takes a walk across the room.Broulard then launches into full attack mode, ensnaring Mireau by appealing to what he knows are Mireau’s weakest points — his vanity and ambition. At first, he hesitates to tell Mireau what’s on his mind; it would surely be misconstrued! Mireau would no doubt misunderstand his motives for mentioning what he has to say. Mireau, more than curious, pushes Broulard to reveal the information. Reluctantly, Broulard tells him that there is talk around headquarters of putting him in charge of the 12th Corps, and with it, the award of an extra star. Mireau makes an impassioned speech about how his men know he loves them, that the life of one of those men means more to him than all the awards in France. There he stands, a man stuffed full of false pride! Broulard isn’t fooled, and delivers the coup de grâce — he will simply go back to HQ and let them know that the General here (that would be Mireau, of course) considers the attack “to be beyond the ability of his men at this time.” Mireau is snared — oh, he never said that, and maybe it is possible after all. How much artillery support could he have? To which Broulard replies enthusiastically, “We’ll see!”

Mireau then asks about reinforcements, to which Broulard responds, “We’ll see, but I feel sure you can get along with what you have.” Mireau now thinks that they might just succeed in the attack, never thinking for one minute that he’s been lured into the trap by flattery and promises of promotion. Or maybe preferring not to.

Apart from the wonderful acting by Menjou and Macready, the whole scene is choreographed like a dance. First, Menjou putting his arm through Macready’s as he leads him around the room, talking about promotions and honor, then Macready doing the same to Menjou when he makes his mind up to do it. It’s a “Dance of Death,” the consequences of which set the stage for the tragedy, blame and recriminations to follow.

SCENE TWO: Well, it has to be the “Attack on the Anthill.”

Along with the legendary opening tracking shot of Col. Dax (Kirk Douglas) as he prepares to lead his men over the top, we have the faces of his men waiting for the order to climb out of the trenches and attack the German lines.

The cuts go back and forth, an unbroken study of fear and courage. Dax reaches the point where he himself will be the first up the ladder when he blows his whistle to start the impossible assault. What we see now is a study in blind faith, blind courage and, ultimately, carnage.

It’s relentless as we watch the men, led by Colonel Dax, charge through no-man’s land, most either cut down by raking machine-gun fire or explosions from mortar shells bursting all around them. It feels endless. The action goes on and on as we focus on Dax, in the middle of the mayhem, drawing us into the epicenter of an attack that we can see before our eyes is pointless and worse than useless; a murderous decision has been made. And as Mireau threatens to put the men still in his trenches under fire from his own guns, and then threatens to let the “little sweethearts” who stayed in the French trenches face French bullets because they wouldn’t face German ones, and after Colonel Dax makes it back to his own trenches, we understand: the attack has definitely failed.

I am always left with the feeling that really, not much has changed. Karl Malantes, in his excellent book What It Is Like to Go to War, writes eloquently about how superior officers would send troops into battle in Vietnam, ill-prepared for the operation they were meant to carry out — but sent, nevertheless — with little justification other than the superior officers’ grab for glory and promotion.

As soon as General Mireau acquiesces to the flattery and empty promises of General Broulard in that first seduction scene, there could only have been one result. Additional artillary fire? “We’ll see!” Replacement troops? “We’ll see, but I feel sure you can get along with what you have.” As in Vietnam and the second Iraq war, the generals prefer to go war with an army they have, but not the one they need.

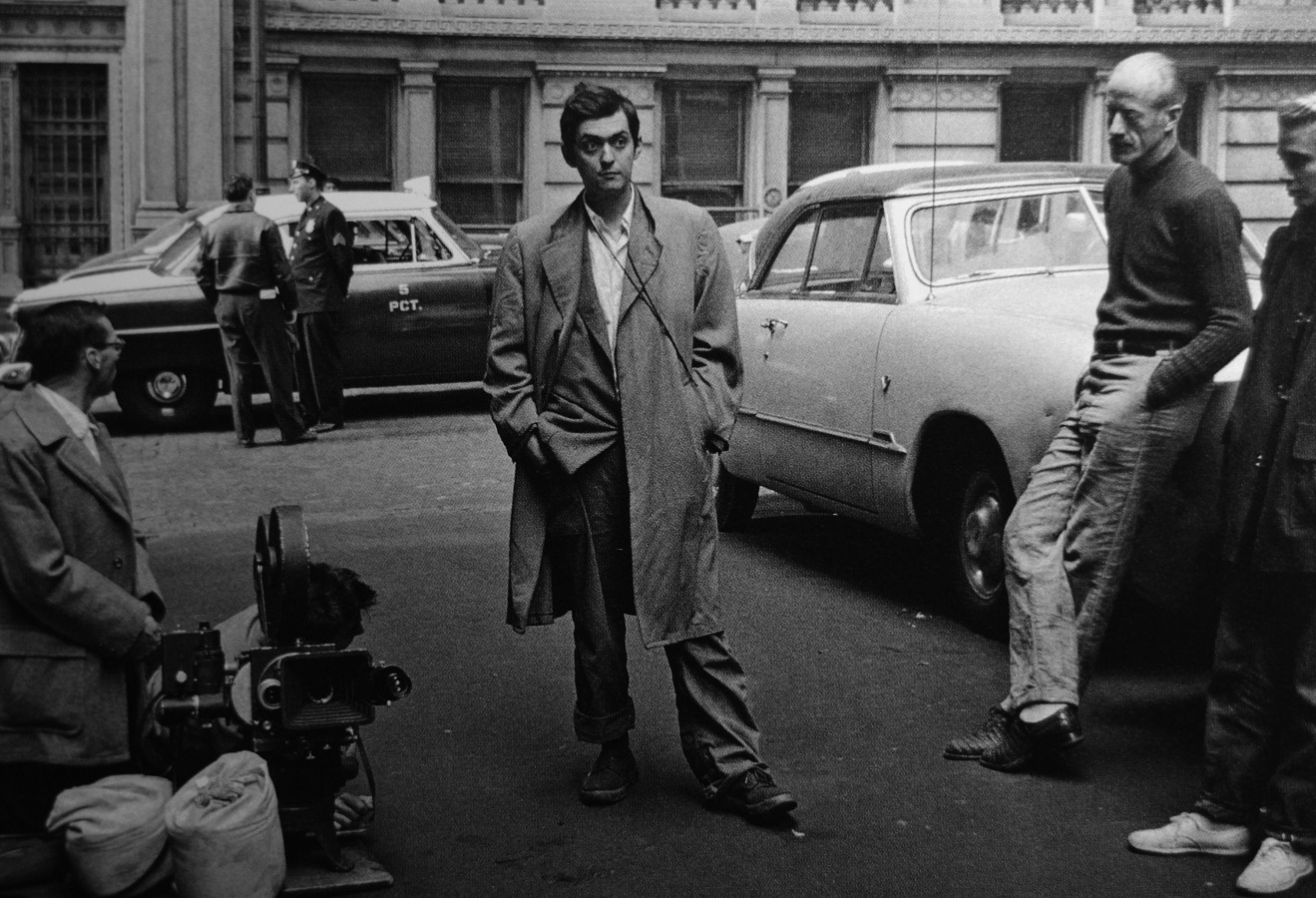

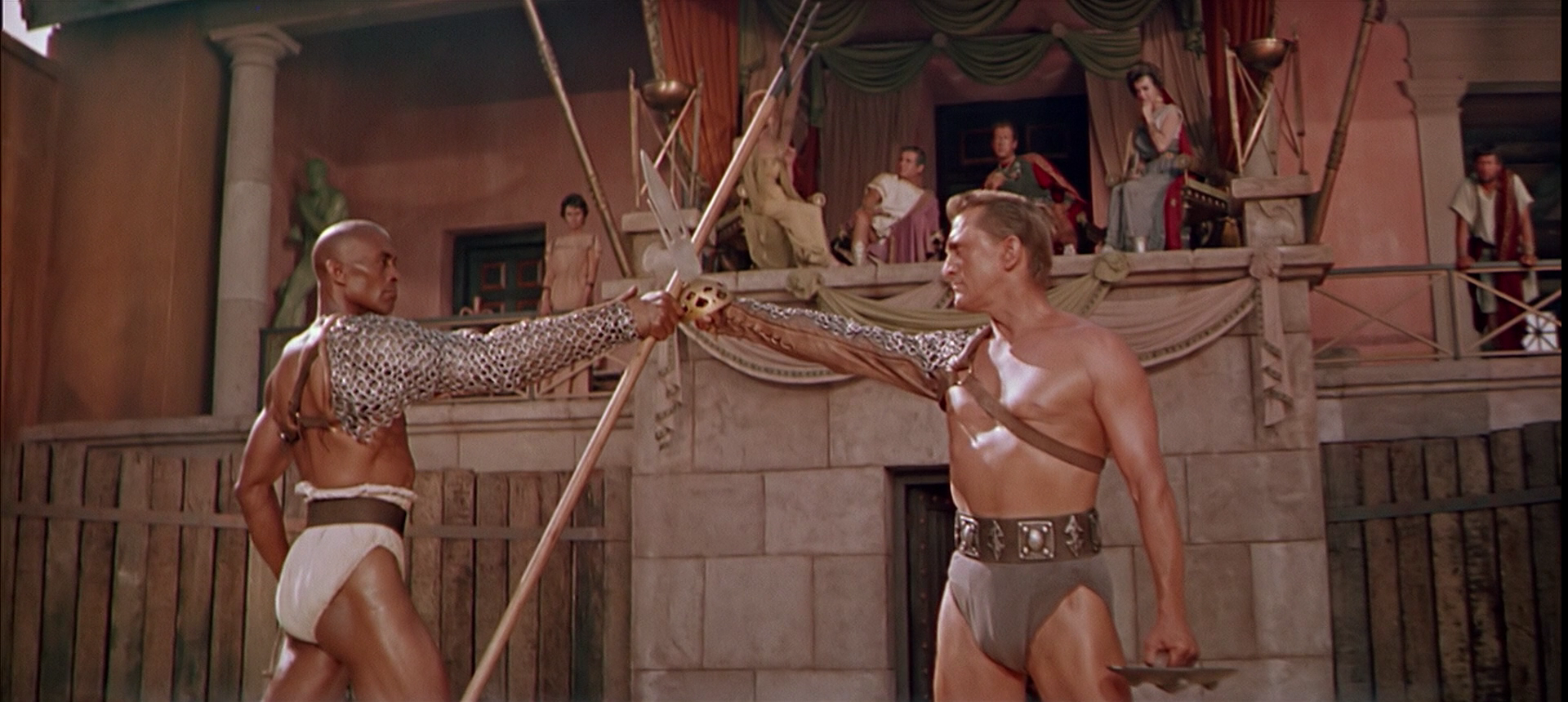

SPARTACUS

Much has been said about how ambivalent Stanley felt about Spartacus, and it’s true — he was. It wasn’t “his film.” That’s how he felt about it, right up to the day he passed. But that doesn’t mean he wasn’t proud of the work he did on it. The two scenes that I especially liked, and gave me an instant, emotional jolt when I first saw the movie, were…

SCENE ONE: The Battle between the Romans and the Spartans.

Apart from directing actors he admired — huge stars such as Olivier, Laughton and Ustinov, who flourished in the theater before they dazzled on the screen —he was particularly proud of the sequences where he felt he did make a difference, such as the massive battle scene. Why? Because it wasn’t in the original script he was handed when he took over from Anthony Mann with only three days notice and a week’s worth of shooting already done. He persuaded Kirk Douglas to include the battle on screen as opposed to off screen, which had been the original intention.Just the awesome sight of the Roman legions lined up in their (for the day) high-tech fighting formations with their super-effective armor and weaponry was enough to make me understand that if I were one of those Spartans waiting for the order to charge, I’d have a pretty bad feeling about the outcome of what was about to happen.We see the Roman army from behind Crassus, the commander-in-chief, and his entourage. Beyond them, hundreds of yards ahead, are the rebellious slaves waiting for them. Then, in a beautifully drilled choreography, wave after wave of Roman soldiers comes onto the scene from behind us, marching down the hill in strict formation toward Spartacus and his not-so-organized army.

More and more of the Romans move into the picture, joining their well-trained colleagues in the advance toward the rebels’ lines; wave upon wave upon wave of them until, not far from where Spartacus’ foot-soldiers stand, they come to a stop. The front ranks of the legion now re-form into a single line of attack. They start to advance up the hill toward the rebels’ front line. Then Spartacus gives the order to light the rolling fire logs down the hill toward the Romans, and battle is joined.

I could feel every brutal spear thrust, every slashing, cutting sword stroke on my skin, as we move into the epicenter of the battle. Of course, it ends badly, especially as Crassus has a massive cavalry reinforcement that seemingly comes out of nowhere, and charges into the flank of the slaves’ army. When I first saw this, it struck me that the reason it stands out as an emotional scene is because of the way it was slowly built up until, at last, the actual charge just had to come. It almost “burst,” like a boil on the skin that’s been watched getting bigger and bigger until, “pop” — it has to burst.

SCENE TWO: “I Am Spartacus!”

Battle over, Spartacus and what remains of his army now in chains, the Roman general, Crassus, is now desperately trying to find either the dead body or the living person of Spartacus. He wants, of course, to make an example of him, in whatever way he can, in the hope that this challenge to Roman authority will never occur again.

With the dejected slaves sitting and awaiting their fate, Crassus declares that though they were slaves, and shall remain so, their lives will be spared if they reveal Spartacus amongst them — or, if he is dead, that they reveal where he lies on the battlefield. If they do not identify him, they will be crucified. Spartacus is about to reveal himself when Antoninus, (played by Tony Curtis) stands and declares that he is Spartacus. He is quickly followed by another slave who does the same, followed by another, and another, until the whole of the captive army is chanting “I am Spartacus” at Crassus.

No need to explain the emotional impact on me. Who wouldn’t love to think there are thousands of people who will stand up for him, even with the threat of hideous death hanging over them? No wonder Spartacus sheds a tear.

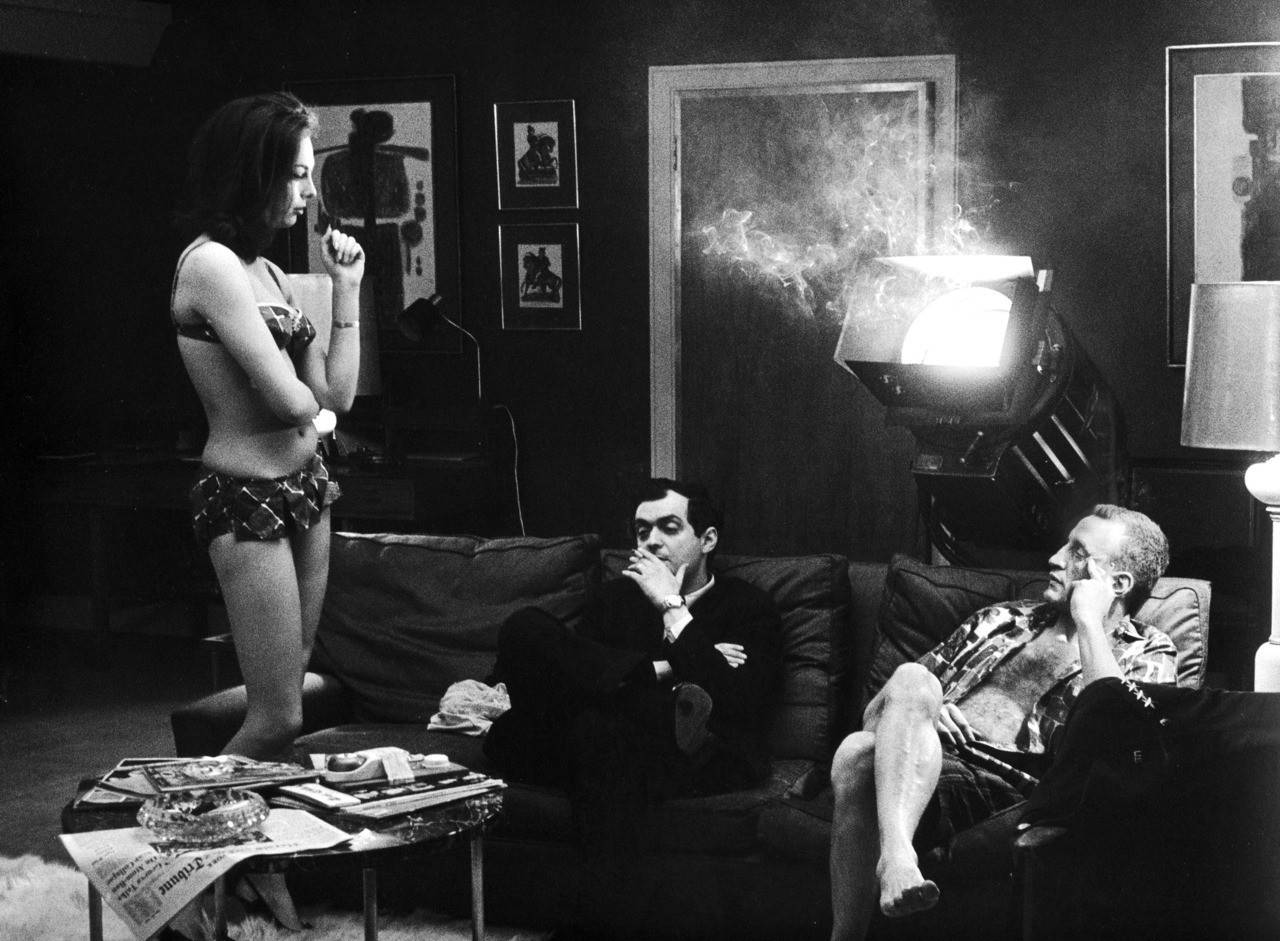

LOLITA

I loved this film from the moment I first saw it. I was still in drama school when I got to see it at a screening in London, and though it had been out there since 1962, that was the first chance I’d ever had to see it.

It’s his most underrated movie, generally speaking, but everything about it, especially its tone, and even more especially the acting (James Mason, Shelley Winters, Peter Sellers and what I thought was an amazing performance from Sue Lyon), spoke to me in my existence as a drama student. Big, broad performances, a style unafraid to show itself as bold, but never losing the connection between being highly expressive yet deadly real. What actor doesn’t want roles like that?

But the two scenes that completely stunned me, and made me want to cry in completely different ways, were two scenes with Shelley Winters.

SCENE ONE: Charlotte Haze’s Attempt to seduce Humbert.

Charlotte Haze (Winters) and Humbert (Mason) have just returned from Lolita’s school prom. Lolita has gone to an after-party, as had been arranged by Charlotte and her friends John and Jean Farlow as a way to clear the decks for Charlotte’s all-out attempt at seducing Humbert.

Charlotte has arranged everything beforehand. There’s party food, champagne — she has even gone upstairs to change into “something more cozy” while Humbert waits downstairs chewing on the nuts left out as an appetizer. When Charlotte arrives, it is revealed that the “something more cozy” is a leopard-skin-patterned dress that she’s almost pouring out of.

“You don’t think it’s a little too…risqué?” she archly inquires of Humbert before she launches into a full-scale attempt to seduce him. “Humbert Humbert…what a thrillingly different name,” she purrs as she pins him into his chair. She tries to teach him how to cha-cha-cha, swaying and wiggling and shaking her décolletage in time to the music. Again, Humbert retreats to the chair, but she drags him to his feet and tries to get him to dance again. When that also fails to work, she pushes him up against a wall from which there seems to be no escape.

She throws herself on Humbert, and is the middle of declaring her love for him, when… Lolita (Lyon) makes a sudden appearance, back from the party supposedly because it was “boring” — though really she has another plan up her sleeve. She teases her mother and, to some extent, Humbert.

Now Charlotte, feeling in competition with her young daughter but not knowing exactly why, is desperate not to lose the initiative she believes she has taken with Humbert, i.e., his seduction. But Lolita continues to provoke her mother and refuses to go to bed. This angers Charlotte so much that she threatens to withhold Lolita’s allowance, and when her young and nubile daughter, Humbert’s real target of desire, does finally go to bed, Charlotte’s anguish at the evening turning into nothing is vented by her hysterical ranting at how Lolita always did spoil everything for her, and is it Charlotte’s fault that she still feels young, and why should Lolita resent it?

“You don’t resent it, do you?” she asks Humbert. “You don’t think I’m just an old-fashioned, romantic American girl?” To which Humbert, taking the opportunity to also withdraw for the evening, thanks her for a charming evening and he, too, makes his way up the stairs to bed. Charlotte is left bitterly disappointed, especially as Humbert dumped the shells from the nuts into her hand upon departing. Charlotte starts to cry, her tears a mixture of anger, embarrassment and, of course, the realization that her grand plan has been totally thwarted. This sad, lonely and pretentious woman is really a sad, lonely and pathetic woman.

SCENE TWO: Charlotte finds the diary entry and confronts Humbert.

Humbert is up early, writing in the diary he keeps locked in a drawer in his room — which, incidentally, is now his office. In the interim, he has seen changes in the Haze household. Lolita is at summer camp, and he is now the husband of Charlotte Haze. He has made a bargain with the devil; the only way he could keep Lolita in his sights was to become a part of the family. Charlotte, insecure as she is, has achieved her main aim — the ensnaring of Humbert Humbert as her trophy. But even better, she has finally got him into her bed.

Charlotte wakes to find that Humbert is not in bed with her. She calls, but Humbert, not wanting to interrupt his “train of thought,” moves to the bathroom and locks himself in to finish what he’s doing.

Charlotte camps outside. A locked door makes her feel insecure, she tells him. She wonders what he does in there that takes so long. She wants to know about the other women in his life. He can only speak to her in patronizing terms, then sends her downstairs to make his coffee like “a good little wife.”

He thinks this clears the coast to go back to his “office” in order to lock his diary back in his desk drawer. At which point, Charlotte bursts into his room, declaring she doesn’t care about all the other women in his past, which takes Humbert by surprise. He clumsily tries to sneak the diary into his drawer.

In an attempt to distract her, he allows her to take him into their bedroom. Humbert, trying to cover up his deceit, allows himself to respond to Charlotte’s seductive purring, but he is distracted by the picture of Lolita on Charlotte’s bedside table. It ends the episode, but there’s also an interruption — the phone rings. It’s Lolita calling from summer camp. She wants to thank Humbert for sending her candy, and Charlotte is not happy about it. She admonishes Humbert for not consulting with her about it. He loses his temper and delivers a vitriolic attack on Charlotte. Humiliated, she leaves the room. By now, Lolita has hung up. Humbert toys with the idea of committing the perfect murder with the gun that Charlotte has shown him — he would explain it away as an accident during a game they were playing.

Humbert finds Charlotte in his room reading his diary. Nervously, he says, “That’s my diary. We don’t read other people’s diary, do we?” Charlotte is humiliated beyond belief, her face full of disgust not only at what she reads about herself, but she now understands fully that Humbert has been after her daughter, that she has been made the unwitting fool in her husband’s sick scheme.

She smacks Humbert with his diary. She reads the entries about her aloud: “The Haze woman,” “the cow,” “brainless, baa, baa…’ Enraged, she screams her contempt: “You’re a disgusting, despicable monster!” She tells him she’s leaving, that he can have the house, in fact everything, but “you are never going to see that miserable brat again!”

Charlotte may have been many things — vulgar, overbearing, pretentious to the extreme, a social climber par excellence. But you’d have to have a hard heart to think she deserved this. And Shelley Winters is pitch perfect. Her face is a collage of hatred, anger and the deep humiliation she feels. It’s real. I felt her pain. It’s the best thing I ever saw her do on screen.

DR. STRANGELOVE OR: HOW I LEARNED TO STOP WORRYING AND LOVE THE BOMB

Following the completion of Full Metal Jacket, we created a new negative for Dr. Strangelove.

What had happened was, for many, many years, Stanley had been trying to find out what had happened to the original negative of Strangelove — the camera negative. In the days when the picture was first released, the studio used to send the negative out to the various territories around the world for printing, for their releases.

I spent about a year and a half (not all day every day, but considerable time) trying to get to the bottom of whatever happened to that negative. In the end, Stanley had to conclude: “Okay. No one can find it. It’s lost and will remain lost.” He decided to gather together the best elements — the various “inter-negatives” that had survived — and create a new negative.

The first we found was too soft — not well-timed in terms of image and lighting quality. Then we looked at what are called “the fine grains,” other copies, early positives made from the original camera negative. But we found that out of the four sets of these, there wasn’t one whose quality was completely intact. None was in fully excellent condition. We would have to mix bits from 1 with 3, or with 4 or with 2. It was painstaking work finding which element was best to print from.

Some bits of footage were shrunk in places. There was “perf” damage along the edges. The laboratory placed these on what they called “a variable pitch printer.” The sprockets could move in and out to accommodate where the shrinkage was — but it had to be set by hand. It was a question of printing a new optimal negative, frame by frame — and by frame, by frame.

In this way we made not one, but four, new negatives, and four new “inter-negatives.” Stanley was determined never to go through such a situation ever again. Not where an element as important as a camera negative gets lost!

They never did find the original negative, but we did find out that there was a little piece of the original camera negative in one of the primary duplicates — and nobody, for the life of them, could explain how it got there. It nevertheless gave us a small clue as to what might have happened. Perhaps the original had never been lost. Perhaps it had been destroyed in some way, an accident at the lab. What actually happened, nobody will ever really know.

SCENE ONE: The first scene in the War Room, when President Muffley and Buck Turgidson confront each other.

The scene that really hits me is when Group Captain Lionel Mandrake first confronts Jack D. Ripper in his office, after he’s given the order to send his attack wing into Russia.

By chance he finds that one un-confiscated radio and discovers that it is still playing civilian music — and so he goes into Ripper’s office. He confronts him, but as a British officer. He talks in this brilliantly, brilliantly conceived and mimicked “officer’s voice.” I know the intonation well because I have a brother who at that time trained at Sandhurst, which is a military college — the British equivalent of West Point. After a couple of weeks, he came back from there on leave, talking exactly the same way as Peter Sellers in the film.

It is a wonderful detail, because I understood from my brother that the purpose served by such a dry, clipped, formal form of speech was to separate your words from emotions. This was true whether you were in the British army, navy or air force. As an officer you would have to order men into battle. You would have to detach emotion from the reality, to preserve a highly effective level of communication between officers.

What becomes so funny is that Mandrake tries to tell Ripper in his polite way that the Russians can’t be attacking. We in the audience, on the other hand, know full well that Ripper is psychotic. Mandrake’s careful discretion is pointless. The attack is simply underway, and Ripper’s not going to do a thing to stop it.

That whole wonderfully, absurdly controlled English way: it isn’t as if Mandrake panics when he realizes that Ripper has gone mad. Instead, he stands straighter, salutes and says: “As an officer in the service of — ” He tries to solve the problem in that ridiculously polished way, without rancor, without losing his temper. Sellers caught it perfectly.

At the same time, you’ve got Sterling Hayden’s excellent performance at his end. He just stares back at Mandrake, at home in his psychotic state, and says: “Why don’t you relax. Fix yourself, fix me a drink with that vodka and rainwater over there.” He invites him to join him in a nice tête-à-tête.

What I love about this scene is that despite the inevitability of this confrontation, there is never a raised voice between them. When Mandrake insists Ripper give him the code, the General uncovers a gun on his desk. Totally unfazed, Mandrake replies: “Am I to understand that you are threatening a brother officer?” It never goes beyond that level of confrontation!

I thought this was a brilliant way of showing that no matter how serious the situation was — and, let’s face it: a world holocaust is pretty serious — there was no way that either was going to reduce his status by losing his temper. Mandrake and Ripper were determined to “agree to disagree.” Neither would do anything to change the situation.

Thus, the consequences were totally inevitable, whether they stopped just one of the planes or all of the planes. The tragedy of the world ending is a direct emotional consequence of that helplessness — of everybody trying so desperately to hang on to their status. Nobody was going to have any influence on something as big as this.

SCENE TWO: Dr. Strangelove’s dissertation on the survival of the planet.

Sellers’ performance drives this moment. Stanley told me there were days when he couldn’t get anything out of Sellers. Whatever he was doing wasn’t of very much use. He would keep three, sometimes four cameras on him.

On the day that things clicked, we have that moment where, as Strangelove, he comes forward in his wheelchair and gives his dissertation on how the planet might survive — a basically and totally chauvinistic vision. In 1963 and ’64, this was very much the prevalent attitude, even in the so-called sophisticated, industrialized world. Many men of the time had this kind of chauvinism deeply ingrained into them. In their minds, it was, and always would be, A Man’s World. Indeed, as Stanley portrays it, the whole tragic charade of what’s about to happen grows out of this male-dominated way of thinking — whether politically or militarily.

Strangelove develops his argument about why it wouldn’t be so bad if this nuclear holocaust actually happened — that although most of the world will be wiped out, and there will be some terrible consequences, we can start anew. Mind you, we would start anew favoring the male half of humanity. Men would lead the way while women would be breeding agents.

Ironically, in recent years when I’ve talked with classes at universities, there are quite a few young feminists who talk of “Stanley’s misogyny.” They fall into the trap of thinking he was a chauvinist himself. I argue that he was not a misogynist or chauvinist at all. Instead, he was saying that there was no way in the foreseeable future that humanity could survive with attitudes the way they were. When he made Strangelove he was pessimistic that it would never change. He was not expressing a personal attitude but making a satire of the world as he found it at that time. It wasn’t a question of him saying, “This is how things should be.” Quite the contrary.

A lot of that stuff was improvised by Peter Sellers on the day, and I thought it was magic. You can even see Peter Ball, who plays the Russian ambassador, on the verge of breaking up, forcing himself to keep a stony face. It took everybody by surprise. Stanley often talked later of having to stuff a handkerchief in his mouth to stifle his own laughter during a take.

2001: A SPACE ODYSSEY

When I saw 2001 I had just finished drama school. The first twenty minutes, I couldn’t believe it. I was with somebody at the time, and I turned to them and said, “Not a word of dialogue yet!” And yet it conveyed everything. It was just beautiful.Oftentimes, people will bring up the same old shot — the bone being thrown in the air. And, you know, the bone in the air is the only exterior shot in the whole film. The hand throws the bone up into the blue sky. Here are my favorites…

SCENE ONE: Heywood Floyd’s lie to the Russians on the space station.

He meets some Russian friends. “Sit down, sit down!” they insist. Heywood reveals he’s going to Clavius. Leonard Rossiter, a wonderful actor who worked twice with Stanley, is the Russian scientist Smyslov. William Sylvester is Floyd. Something strange is going on there. One of our rocket ships was denied permission to land, says Smyslov. Everything is very friendly, very polite on the surface, but there is a strong underlying tension. “We’ve heard there’s some kind of epidemic there,” the Russian says to Floyd, whose response is, “I’m not at liberty to comment.”Apparently, a Soviet craft dealing with an emergency had been denied permission to land at the American base, and this is a source of serious concern — if there is some unknown illness up there, it jeopardizes everyone. Smyslov asks him directly, but Floyd just sits there with a blank face. He “sells” the lie. It is a marvelously layered piece of acting: You know he’s lying. Even though we don’t know yet what it is, we buy it. We understand he’s covering up. And it’s played so naturalistically.

SCENE TWO: Dave Bowman’s “exercise run” on the spaceship.

The exercise wheel: the blue light, the sarcophagi containing the hibernating scientists as the astronaut jogs by in solitude. There was a melancholy about it, which absolutely grabbed me. The cold loneliness of outer space, which is not a feeling anyone had communicated before. Prior to 2001, outer space was all adventure, and zap-zap. It’s strange to say, but when I started working for Stanley in production, we found ourselves working together until three or four in the morning; it echoed exactly that kind of splendid isolation one felt in the film.

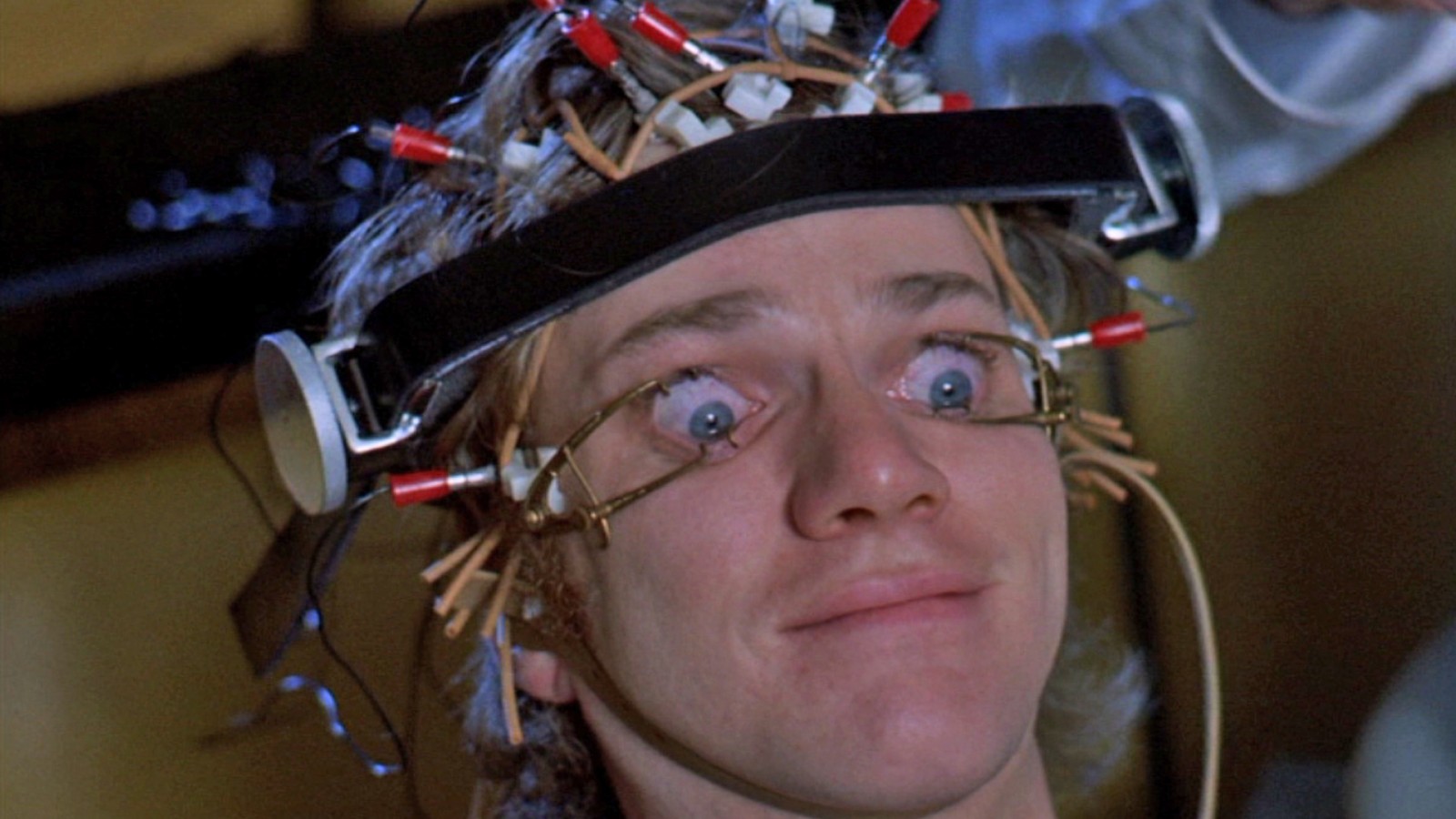

A CLOCKWORK ORANGE

SCENE ONE: Opening scene of Alex raising his glass to us, the audience.

This is, of course, an iconic shot, the long, slow pulling back as we are introduced to Alex, and his world. He’s raising his glass of moloko milk as he looks straight into the camera. He’s saying hello to us. I’d never seen anything like it before. We obviously have a bad one on our hands here. This was an antihero I’d never seen before, and obviously he’s the star of the film, so he’s going to be in it from beginning to end.

Stanley hadn’t noticed until he’d watched the rushes that Malcolm had actually raised his glass in that way. He was his own camera operator for this shot — as he often was — and he had concentrated so completely on the technical and atmospheric considerations of getting the shot right that he didn’t notice until he took a look the next day. But he liked it, so he used it.

SCENE TWO: When Alex returns home from prison to find his room rented out.

It’s beautifully done because it teeters on the edge of feeling like it could all be a little too much, but it isn’t. And you have Joe, the lodger who has displaced Alex in his parents’ affections while Alex was serving his prison sentence, and there’s absolutely nothing that his parents will do to change the situation, to allow Alex back into their lives.

“We can’t really throw him out, can we? He’s already paid two weeks rent.” Like that’s an insurmountable problem. You understand that his parents do not want him. And Joe says, “I’ve heard about you and everything you’ve done. And a lot of it sickened me.” It made me feel for Alex. It made you think, well, what hope is there for him? What happens for real? People come out of prison and have served their time, they’ve paid their dues, and yet they’re left quite stranded and without any hope, really. So here you had two great contrasts. That full-on idea and then the absolute bottom of the world.

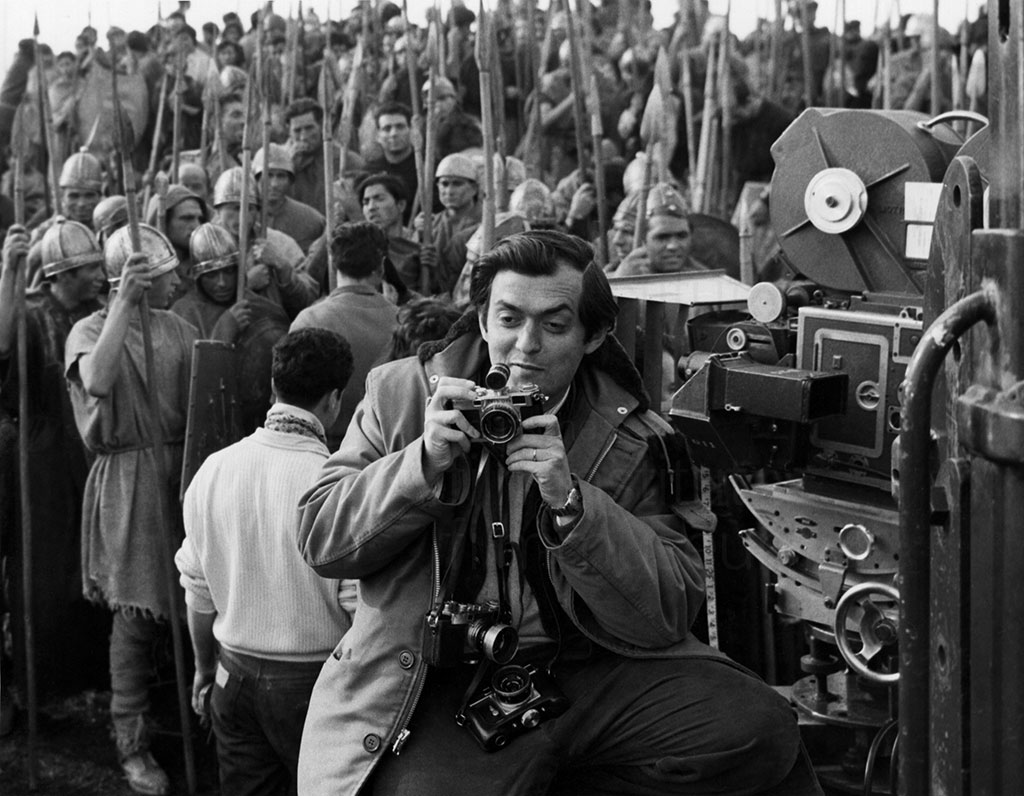

BARRY LYNDON

Working on Barry Lyndon with Stanley was like working with a theatre director. He offered the closest thing to the kind of direction you got in the theatre because he’d let you work it and work it and work it until he felt you got it right. And once you got it right, you were pushed to do it better.The way you started with Stanley, he was always like, “Show me what you are going to do.” It wasn’t like he would tell you, “Now, I want you to walk over there and put your hand here.” It wasn’t that kind of direction at all. It was, “Show me what you got, and we’ll just push it until we get it right.” And that was the wonderful thing about him.But he wasn’t always doing dozens and dozens of takes. There was stuff inside the barn where I did one or two takes. He was happy with that if it looked and felt right. Then we’d move on. Because what he’d do is, he’d attach different lenses to a viewfinder and walk around, looking at you, trying to find his first shot. Once he found his first shot, everything else would grow exponentially: very organic. By the time he was getting into the real shooting, apparently you weren’t thinking about yourself as an actor at all. It would come, second nature. Same with dialogue: You just worked the dialogue, went over it and over it and over it. You had to do your homework so you could say it without remembering it. Those words were so embedded in your brain by that time, there was no way you were going to have any problems.This is apropos, for the scene I was asked to really study and learn before we shot it was the one in which I interrupt the family’s high-society concert by bringing in David Morley — who plays Barry’s son Brian, my little half-brother — into the music room, clopping on the hardwood in my shoes. Stanley gave me the dialogue to memorize for that just after I arrived in Salisbury, England, where we were shooting.

I’d be called to the set at about three in the afternoon in full wardrobe and makeup. I was told to sit outside and wait for them to finish shooting the scene they were working on until they wrapped the day at six. I would be called on set and Stanley said, “Do you know that speech?” I’d say, “Yes,” and he’d say, “Do it for me then,” and I did. Then he’d shake my hand and I’d go back to the hotel. The next day we did it again. Again I showed up at three; again I waited until six, then performed the bit for Stanley alone after everybody else had been cleared away. We did that for four days in a row. Finally he said, “OK, you won’t have to do this again.”

Originally that was to be my only dialogue scene, but after we’d shot it, Stanley sat me down and said: “I liked what you’ve done. I’m going to write a whole bunch more scenes for you.” I felt like I had just smoked the biggest, fattest joint — I was so high. I had seen his films and had said I wanted to work with him, but didn’t know if I would ever get to. And I did.

While I was waiting outside the set, I would just look around to see hundreds of cars and trucks, enormous lights outside these huge, stately houses we filmed in, and dozens and dozens of people, and I just thought, “My God, here’s this one guy with an idea, and look at all this.” He let me come on the set, which he rarely allowed. I told him I was thinking I might want to work in production instead of as an actor, and he said, “Well, if you can show me that you are serious about it.” After filming wrapped I took a couple of television jobs as an actor, but then moved for a time to Stockholm, Sweden, where I met someone and got married and got a job working in a cutting room. I let Stanley know.

One day he sent me a copy of Stephen King’s novel The Shining with a Post-it note: “Read this!” I read it that day. The next evening he called: “Did you read it?!” And I said, “Yes, I did.” Then he asked me if I wanted to go to the States and look for the little boy. This is because on Barry Lyndon I’d been able to help with young David Morley, who played my brother Brian. It’s hard for young children on a film set. David was understandably fidgety. Other grownups were at a loss to help him. I’m comfortable with kids, so I took him firmly by the shoulders and said simply, “Concentrate.” There was a lot of interference at the time, but Stanley said: “Let Leon handle it.”

SCENE ONE: When Redmond meets the highwayman and his nephew.

Redmond Barry has survived his first duel. He’s been packed off with a fine horse and a satchel full of money with which to begin his life in the world. He is full of energy and optimism. At a tavern, he pauses for a bit of water and is sized up by two men, one older and the other a younger man.

It is a wonderful, dark moment, laced with such fascinating humor, and Stanley pulls it off in a set of simple shots. The elder of the two men says by way of introduction, “Good day to you, young sir. Would you like something to drink?” To which Barry responds “No, thank you.” The old man persists: “Would you like something to eat?” Again, Barry declines: ‘I must be on my way.” We’re left with the two men just smirking at the innocent Barry, and we know from that moment, something is going to happen.

What we feel from these two men is that, one, they have an agenda. Two, they are in heaven that such luck should cross their path. They are two predators discovering their next meal, and could not be more delighted. In the next scene, riding deep into the woods, Barry sees the figure of a man up ahead standing with his back to his approach, next to a fallen tree that blocks the road. The music is the fast beating of a hand-drum and the wailing of a pipe playing a plaintive, haunting melody. That drum is Barry’s heart, unsure of what is to happen. When he reaches the man, he turns to face Barry, up there on his horse, and points two pistols at him. Barry sees he is the older man from the inn. The younger one rides up behind him, cutting Barry’s only option to retreat. Thereafter, Barry is divested of all the money his mother gave him, his father’s pistol and sword, even his horse — all done in the most gentlemanly and courteous manner!

The scene is extremely meaningful in relation to the rest of the story. Had Barry come by the tavern five minutes later, the two men might well have departed, and Barry would never have been robbed in the woods. His entire life would have been different. It was a great preoccupation of Stanley’s that our lives are built around such moments of chance.

SCENE TWO: When the British army makes an attack through the orchard.

We start the scene with a close formation of English troops marching meaningfully, bayonets affixed to muskets and with their commander walking bravely at the front, sword carried ceremonially, and pull out as Stanley tracks them from the side. We then cut to what they are attacking, or advancing toward — the Swedes and the French, lined up in “firing formation,” just waiting for them to come into range.Back and forth we cut, the English in their tight formation, then the Swedes and the French strung across the orchard, priming their muskets. The English keep advancing, the enemy are given the order to aim. Still the English advance, muskets in hand, marching into certain death.There is the French cry of “Fire,” and the English fall, only for the gaps in their ranks to be filled by those soldiers coming up behind. Another volley; more English casualties. Finally, the commanding officer, Barry’s mentor, is hit, and we leave the scene with Barry carrying his friend over his shoulder to a place of safety. As his friend dies (bequeathing Barry the remainder of the money he has left), we hear the order from an English officer to charge the enemy’s lines.When I first saw this scene at a screening in London for the press, and as I later said to Stanley, it was a grotesque lesson in 17th century military tactics.

They had muskets in their hands, for Christ’s sake, yet they still marched into an attack as if they were carrying spears and swords. What were they thinking? Or not thinking, for that matter?

It was chilling; it made me angry that men’s lives could be so nonchalantly tossed away. It was revealing in the heartless waste of human life for the sake of formality and old-fashioned — and, let’s be honest, moronic — “this is the proper way to conduct an attack” logic.

THE SHINING

I saw 4,000 children over six months. When little Danny Lloyd came in to audition, he broke all the rules of protocol that we had set. Stanley and I agreed if they don’t want to come into the room without their mom and dad, then forget ’em. That was the protocol I had always followed up to that point. But Danny wouldn’t come in without his parents.After a good few minutes of persuasion from his older brother, his mother, Anne, and myself, I finally coaxed him into the room, on his own, with me. We sat down, facing each other, and he said nothing for a good five minutes. Then he just said, “I like your suit.” From then on, it was fantastic. We got him back two or three times to improvise, and he was wonderful. His concentration was incredible. He only acted in one other thing. His parents didn’t like Los Angeles. I believe he’s a teacher now.

SCENE ONE: The iconic shot of Danny cycling around the hotel halls and lounge.

Stanley had tried lots of different ways to shoot this scene, and felt it would work best if we were at the exact level of Danny with his tricycle. The closest we could get to the floor just wasn’t close enough. Stanley said to Garrett Brown, who invented the Steadicam and was operating, “Can’t you hold it lower?” Brown replied that he couldn’t, “Because it’s not designed for that.” He had the camera atop a pole that stood upright by about four feet, which he could move comfortably.

Stanley said, “Why don’t you secure the camera upside down, at the top of the pole?” Garrett had to do a little engineering. He went off for twenty minutes, and when he came back, he had worked it out. Stanley then worked at getting the right distance with the right lens so that moving close behind Danny, you could see the periphery around him at all times. Then we went riding around the lounge and the corridors of the hotel.

Problem was, Garrett was sitting in a wheelchair as he operated. Three of us were pushing him around, but every time we came to one of the rugs in the path of where we were going, there was a sudden drag from the tires as they hit the woolen rugs. It was very noticeable as Stanley watched the monitor. Stanley was going to remove the carpet, but then one of the crew said, “I like the sound it makes.” Stanley asked, “What sound?’ To which the reply was, “The sound of Danny’s bike on the wood, then on the carpets.” Our sound guy, Ivan Sharrock, always recorded the rehearsals, and he let Stanley hear the sound on his headphones. Stanley said, “You’re right.”

So now we had to solve this problem. In the end, we inflated the tires to the point of exploding. As long as you knew the bump was coming up, you could kind of compensate with either an extra lift or a push for it, because the Steadicam wouldn’t register the dip visually.

Of course, it became that beautiful thing: having Danny just going around and around the lounge and the corridor. You’re right behind him, at his level, and see him at a wide angle. And because Stanley used a wide-angle lens, you could see everything around him — the top of the balcony, the whole periphery of the room and corridors he cycled through. You get a sense of impending doom.

This scene has always meant an awful lot to me because of Stanley’s openness to collaboration. Everyone talks about Stanley being a control freak, and of course he could be, and get into the truly minute details of equipment and preparation — but when it came to problem solving, to pushing through to a good idea, he didn’t care where it came from. If it was good, he’d say, “Let’s try it.” That’s how open he was to others’ suggestions, no matter where they came from.

SCENE TWO: When Halloran gets axed by Jack.

We used to spend ages walking around the sets trying to figure out where Halloran was going to get it. Where’s he going to get it?! Where’s he gonna get the axe? We patrolled the halls in moments of downtime, discussing every option. After awhile, my idea was, having seen him come all this way across the country, it should be as soon as he walks through the door. He should get it immediately then. Stanley said, “That’s really a crappy idea. That’s stupid, Leon.” And then, about a day later, he said, “The shock is not that Halloran is going to get killed. It’s knowing that he’s going to get killed, but making him wait for it.” That’s why Stanley took it down very slowly through the lobby and Jack springs out. It’s terrifying. Even though I saw it rehearsed many times, it’s still terrifying to me when I watch it in the film. The suspense is when he’s going to get it and where he’s going to get it. We knew from the moment he entered the hotel that he was going to get it.

FULL METAL JACKET

Lee Ermey started off as a technical advisor, and then got the role of Hartman in the end. That had to do with the way that we were auditioning platoon extras. We went to the territorial army, which is the home guard here. Originally, we were just sitting him down in front of a camera asking name, age, what do you do, etc. Then we thought, well, what are we going to find out doing that? Because Lee, who was a really proud Marine, would always turn up on set absolutely pristine, and he told me about when the new recruits got off the bus, the D.I.’s — Drill Instructors — had a good cop, bad cop approach to the new guys. One of the D.I.’s would hammer them and break them down and make them feel stupid, while the other two would be the mentors for these young, raw recruits.I asked Lee if it wouldn’t be better just to line them up just like they would have done at the boot camp where Lee was stationed, and then he could go to them one by one and give them his best lines of abuse. So he did, and I videotaped it. When Stanley saw the tape, he just fell over laughing. We had something like 800 pages of transcript from those recordings, and it boiled down to lines like “Who’s the slimy little communist shit twinkle-toed cocksucker down here, who just signed his own death warrant?!” or “I bet you’re the kind of guy who would fuck a person in the ass and not have the goddamn, common courtesy to give him a reach-around.” All of that opening diatribe in the barracks came from these tapes I’d shot and recorded. It was amazing. There again, you see the contribution of someone like Lee, and the authenticity he brought to it. He could terrify those guys, even though they knew they were on a film set.

And, of course, think of how Stanley seized the opportunity and used it. It gave the whole scene a veracity that we would never have achieved if we had gone with how the scene had been originally written.

SCENE ONE: The run up the road to clear the path for the tanks.

Lee had done two or three tours in Vietnam, and knew the formation of how they would advance up the roadway. So when those mortars go off, and their commanding officer goes down behind the tank, he gave us the maneuvers — the leapfrogging the Marines would have used to make it up that road. It meant it would be very difficult to keep any individual target the enemy might be trying to cut down for any great length of time. The enemy wouldn’t know when a Marine would re-emerge and continue his run up to the building they were hunkered down in.

I also have an attachment to this scene because I did all the footfalls and foleys on Full Metal Jacket. So all that gear I had to have on me when I did it in postproduction was the stuff we used in the film. It was fun to find a rhythm in the gear, as it jangled while running. It created, well, almost a music of its own. The music on the soundtrack is very spare there, but you can still hear the boots and gear as you go up that road. It makes for a beautiful sequence. And this film is really an extension of Strangelove — when the U.S. Army raid the airbase that Ripper commands.

Stanley was proud of that scene. He had decided to try to shoot that scene in a vérité style, and when Strangelove came out in 1964, it was a pretty bold thing to do. This scene only took eight or nine takes. But the Steadicam guy was on his knees half the time. That brought a vérité of its own because he was swaying a little bit and it perfectly suited the feeling of a cameraman following these guys up the road toward the building where the V.C. were holding out. It gave a unique perspective to how these Marines would have been feeling as they ran toward their quarry.

SCENE TWO: The sequence from tanks firing to the lift-off of the helicopter.

I’m speaking of the bits that follow the long assault on the Citadel of Hue, following the moment when Crazy Earl gives us a look and the thumbs up.

I’ve always loved this scene. You have a documentary camera crew on foot, visible in the frame, and the song “Surfin’ Bird” by the Trashmen yammering away in the background. A couple things I recall about producing this moment: When the tanks fired and the shells hit, you didn’t get the bang until a second or two after. At first Stanley was going to correct this, sync it up in post, but when he looked at the rushes, he thought, “Wait a minute, this is more realistic.” In life, you would see a shell hit, but not get the report until a couple of seconds afterwards. That was the logic.

The central principle in filming this scene was to emphasize the feeling of how the Vietnam War was becoming, more and more, “the TV war.” The documentary crew prowls along the wall where all the Marines are taking cover. The tanks fire off their rounds on the distant building, stretcher-bearers carry the wounded away, a marine, face completely bandaged, waves to the documentary cameraman. Stanley carefully selected and built up what we see in this long tracking shot beside the wall. This was all taken from thousands of photographs, bits of documentary footage we had as research. He stitched this whole thing together, and once we come to the end of the wall and finish, the fragments of dialogue end with the line, “We’ll let the gooks play the Indians!”

Stanley thought he had the picture power, but what music should he use under it? As he used to cut his scenes using music, he remembered a track we used to laugh at simply because it was so crazy — just crazy, you know?

So Stanley finally tried “Surfin’ Bird,” and he discovered to his great pleasure that it synchronized perfectly with what he had, from the start of the scene to the end of it — to the frame! He didn’t have to cut a frame or extend a frame of film — it was, from start to finish, complete and beautiful synchronization, a beautiful piece of serendipity. It wasn’t just the acting. It wasn’t just the action. It wasn’t just the music. Everything came together. Some of us were doing thirty-six-hour days. So when something like that happens, you’re on your knees thanking God. We went home early that night.

EYES WIDE SHUT

We shot the first scene – the party scene – with Harvey Keitel, playing the part of the powerful doctor that was later taken over by Sydney Pollack. We planned to shoot the scene in the bathroom with the girl using Keitel in this big stately house in Hatfield, (though originally it was set in a library, along with the red snooker table we used in the final scene between Sydney and Tom) outside of London, but it took so long to set up that, by the time we came to the end of the day Stanley realized that Harvey had been in London for weeks and weeks and weeks now – and he had other commitments pending. So he left and we got hold of Sydney, who had a particular gravitas that worked well with the part. Harvey was so energetic that you could believe there was something sinister about the character. With Sydney there was more of a surprise when he reveals that he is part of that other world of the secret orgies. Sydney brought another dimension to the role. Harvey’s a wonderful actor but you kind of expected him to be sleazy and underhanded. Sydney came across respectable.

There was a similar difficulty of scheduling that happened with Jennifer Jason Leigh, and a creative change as well. She not only had to go do another job – eXistenZ, for director David Cronenberg – Stanley saw a fresh way to rework the script. He thought: “Wait a minute. We have two scenes here with this character but I can telescope them into one.” It became a more effective scene when it was combined. There was a totally different feeling about it. Originally this encounter between the doctor played by Tom Cruise and the daughter of a dying patient was going to be shot in a hotel suite. When Stanley reconceived it we built the set in the studio instead – which Stanley loved, of course, because now it meant he could control the light every second of the way and actually not worry about how long it might take to shoot it.

As I’d been casting on his behalf for Aryan Papers, I had all these videotapes that had been sent in from every territory in Europe and carefully archived. When it was clear Jennifer was no longer available, Stanley said, “We should look for something different. Why does she have to be American?” And I recalled Marie Richardson’s tape. I knew her when I lived in Sweden and of course I’d seen her excellent stage work with Ingmar Bergman, so I showed her tape to Stanley and he said, “Yes.” I got her over on the plane to meet him. As I left to take her back to the airport, Stanley whispered: “Wait until just before she goes through the gate – then tell her she got the role.” I did exactly that – I waited for her walk up to the gate and told her: “Oh by the way – Marie – Stanley wanted me to let you know, you got the part!” It must have been the most unusual way she’d ever heard about getting a role.

SCENE ONE: The argument in the bedroom when Alice reveals her secret to Bill.

This scene took a long time to shoot. You had Nicole Kidman, who is such a beautiful, wonderful actress, and Stanley, who didn’t direct her but just let the scene grow, as he normally did anyway. He hardly ever directed actors. And Tom Cruise was playing this naïve man who was selfish and thought he had the perfect life with the perfect wife, perfect daughter, perfect apartment, knew all the right people. So when Alice reveals to him, after they get stoned, her inner secret, and that she thinks he’s arrogant, he thinks she gets aggressive when she’s smoking.

It’s a lovely piece of acting by Tom that he doesn’t get enough credit for. You can actually see in his face how he’s getting more and more demolished with everything that she tells him. Even when we were shooting it, you could see it happening. It was beautiful watching Stanley work with them, and how they responded. How persistent and patient they all were. It took days to put that together, but it was so worth it.

I love that we had the ability to work slowly and building and seeing how things just came together, because you didn’t have anywhere else to go. An actor can be on the job for a week, a month or a year, but there’ll still be a middle period where that boredom falls. I know. I’ve been there. But once you break through that boredom, once you understand that that boredom is just a stage, and once you come through that boredom, once you just accept what you’re working with, that’s when you’ve got no resistance anymore. That’s when things start happening. It’s so beautiful to watch.

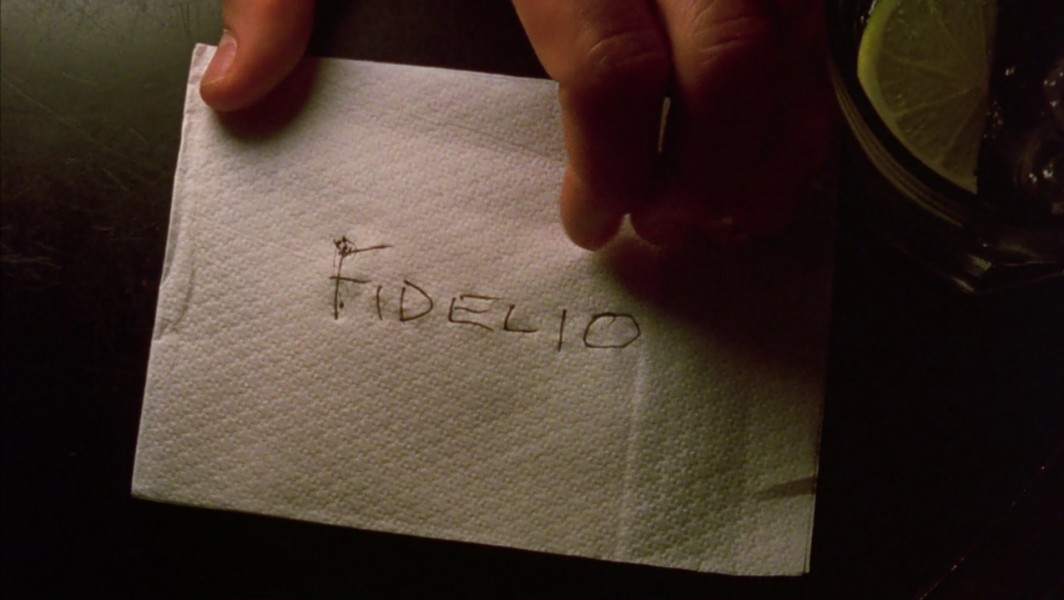

SCENE TWO: Bill’s entry into the marble hall at the beginning of the masked ball.

There were two things about this scene. There were a lot of rumors about these sadomasochistic clubs in New York. It was totally exclusive, very high-end society. This was all part of this life that Bill leads, and how shocked he was by Alice, and now he can maybe take his revenge. He finds out about a house where his friend, Nick Nightingale, is playing for what the pianist hints at being something erotic. Bill enters the house, having conned Nightingale to tell him the password, and witnesses what can only be described as an orgy.

It had taken ages, ages and ages to find how we were going to do this scene. I had dancers whom I’d auditioned for it. Yolanda Smith, who had her own abstract ballet company, helped me work out rituals. Originally, we thought maybe it should be a set-up akin to the choreography pioneered by Pina Bausch, which is built upon a constant, ritualistic repetition of gestures.

It was a little seed of an idea, but after weeks and weeks — actually months and months by the time we finished — there were not only dancers, but also models as part of the scene, which had grown in scale and size, all set in this huge, hard-carved marble room. It was great for me to be a part of filming something quite unique, amazing and, in a way, weird and scary at the same time.

During the shooting, Stanley would say, on any given day, “O.K., Leon, you’re going to do this today.” So when Bill Hartford comes in through the door, I’m the one who takes his coat. That’s me in the mask. And when he walks through the next door, that’s me in the mask. When he walks into the hall and looks up into the balcony, that’s me in the mask he’s looking at. And it’s me who takes the girl, just in different masks. And, of course, I played the guy in the red cloak, too. Those scenes took seven weeks to shoot. It was a blast.