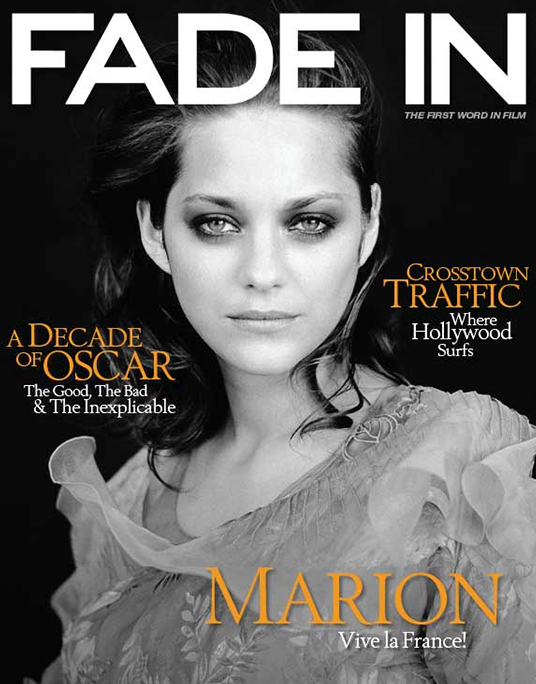

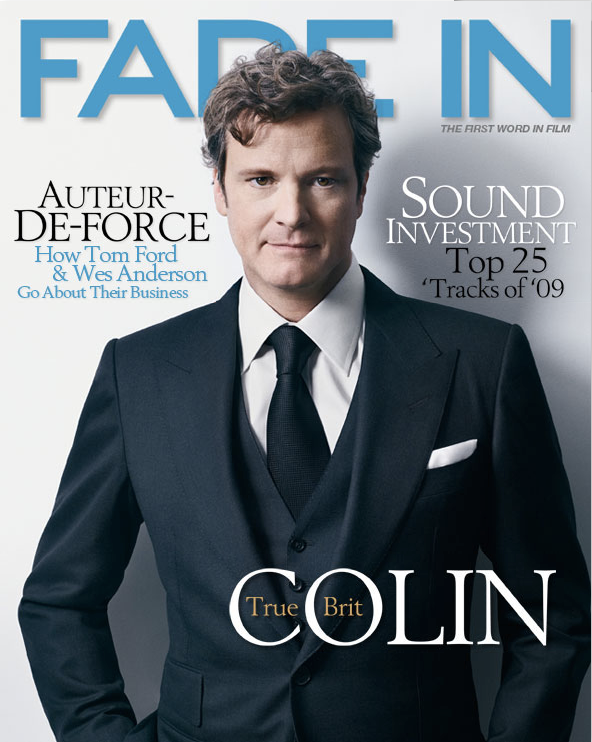

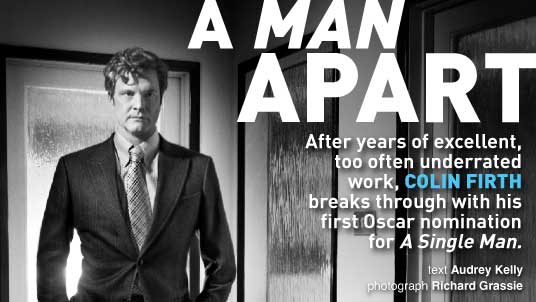

Single Man marks a significant career milestone for Firth, earning him his first Oscar nomination for Best Actor for his performance as George Falconer, a gay British professor mourning the loss of his late lover during one bittersweet Los Angeles day in 1962.

Single Man marks a significant career milestone for Firth, earning him his first Oscar nomination for Best Actor for his performance as George Falconer, a gay British professor mourning the loss of his late lover during one bittersweet Los Angeles day in 1962.

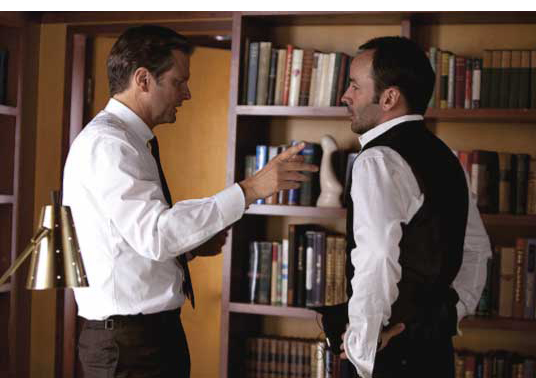

Adapted from the novel by Christopher Isherwood by first-time director Tom Ford — best known as the creative force behind the fashion house Gucci — A Single Man has been frequently (and, it must be said, lazily) described as “a gay film.” But Firth sees it as a story with resonance for anyone who has experienced loss or longing — in other words, just about everyone on the planet.

Like his countryman Hugh Grant, who was born one day before him, and to whom he has often been compared, Firth made his first major public splash in 1995, in the acclaimed BBC miniseries adaptation of Jane Austen’s Pride & Prejudice, while Grant was starring in Four Weddings and a Funeral. In the years since, Grant, with whom Firth vied for Renée Zellweger’s attention in Bridget Jones’s Diary and its sequel, has achieved greater mainstream success. But while Grant has rarely strayed from his rom-com comfort zone, Firth has quietly and steadily built one of the more varied and enviable resumes in the business, ranging from period dramas like Girl With a Pearl Earring to boutique indies like A Single Man, kid fare like St. Trinian’s and the glossy romp of Mamma Mia!

Not surprising to those familiar with his longtime devotion to social justice, Firth’s recent breakthrough on both the commercial and awards front has not shaken his deeply held political beliefs. Indeed, during his interview with Fade In, which took place shortly before the announcement of the Oscar nominations on February 2, Firth showed far more interest in human rights and NGOs than in back-end deals and opening weekend grosses. Which in some quarters will no doubt single him out for even greater respect than his work in A Single Man.

![]() ow do you feel about all this awards attention you’re getting for A Single Man — bemused, like it’s about damn time or something else? [Laughs] No. It’s neither, actually. I don’t feel it’s owed to me in any way. If people happen to respond in a certain way to the film, it’s nobody’s fault but my own. I make my choices. I have the qualities I have. There’s no entitlement there. I’m the one who has put myself up there and, in a sense, said: “Watch me.” I don’t think anyone has the right to say, “I deserve to be applauded.” It’s very presumptuous, really, [to expect] people to pay attention to what you do.

ow do you feel about all this awards attention you’re getting for A Single Man — bemused, like it’s about damn time or something else? [Laughs] No. It’s neither, actually. I don’t feel it’s owed to me in any way. If people happen to respond in a certain way to the film, it’s nobody’s fault but my own. I make my choices. I have the qualities I have. There’s no entitlement there. I’m the one who has put myself up there and, in a sense, said: “Watch me.” I don’t think anyone has the right to say, “I deserve to be applauded.” It’s very presumptuous, really, [to expect] people to pay attention to what you do.

What’s nice is, to be in my fiftieth year and to be having something happening to me that I’m not jaded about. I’ve been very, very fortunate. The enemy for me has not been unemployment, and that is a great blessing. But if you’re lucky enough to be constantly in work, then the enemy could become a place where you take things for granted. I’ve seen that happen to other actors. And I’ve seen actors learn to despise all the trappings that accompany you along the way, and it’s a mistake. It’s a way of taking it too seriously if you say, “This is all nonsense” — the awards and the fawning and all the first-class travel and all the things that happen to the very few, lucky actors that get treated that way.

I remember a friend of mine giving me advice many years ago, when I was in my twenties, when a job came along that looked like it could be something that could have projected me into the stratosphere. He needn’t have worried, because it didn’t. But he said, “If that happens, don’t lose your sense of fun. Don’t lose your sense of the ridiculous. It’s a way of taking it too seriously. Don’t become disgusted with it.” And I thought that was very good advice. He said, “Only silly people become divas.” The danger with —

and I’ve seen this happen to my peers at times — the more intelligent actors I know who have a huge amount of success is that that happens.

They start to think that there’s a kind of living for it all, a feeling of guilt or shame about it. I don’t know. I haven’t really had to suffer all that. I’ve had a fairly gentle trajectory of pleasant surprises and disappointments that have nudged me along for the last twenty-five or thirty years. I’ve learned to manage my expectations, both my optimistic and pessimistic ones. But [the attention for A Single Man] is exceptional because I’ve learned not to expect any of this. If it stops here and goes as far as this, this is plenty to have banked. I know it’s a cliché for actors to go around saying, “It’s an honor just to be nominated, etc., etc.” But it doesn’t have to get much better than this. So, quite frankly, when you take a risk on a film, which is operating on a tiny scale, a twenty-one-day shoot that no one is being paid for, the experience becomes quite personal. It’s all the more satisfying to see it actually get out there and get seen and get the love that it’s getting. It’s probably one of the most satisfying moments I can remember. And any buzz really helps just getting people in to see it.

Do you find it odd then when people say to you, “This movie’s going to change your life”? I’ve heard it all before. A long time ago I might have been tempted to believe it. Everything changes your life; every tiny thing changes your life. Your life is altered every time something happens; it’s like some little fork in the road. And it probably will change my life. But I will never ever know how to quantify that change. I can look back over twenty years and look at moments and think, “Yes, that probably changed me,” but I don’t know how, because you don’t know what would have happened otherwise. The only way you can analyze the meaning of the change of life is to know what would have happened if you had not done that, and no one can ever know that. So, yeah, it will change my life, but I don’t think it will change my life necessarily in the way that people might mean it, like everything will be great from now on. No. I don’t think so. You’re more determined by your character than by these moments of good fortune, or whatever you want to call it. If it’s my nature to constantly go back to doing what I did before, then I’ll probably do that.

It might not get easier. It could get harder. It might. That’s true. A lot of things that appear to be blessings have a tendency to be a burden of some kind, and the reverse is true. I find those kinds of paradoxes quite appealing, really. I heard an anecdote about a doctor who would tell his patients, when they came to him saying something wonderful happened to them, like, “I just got a pay raise,” “Everything is wonderful,” he would say, “I’m so sorry to hear that. I’m sure with a lot of care and help it will work out for you.” Then, conversely, if they came to him saying, “I’ve just found out I have a terrible illness,” “My wife’s left me,” he would say, “Let’s open the champagne! This is the most fruitful, productive moment of your life!” I tend to think we should be circumspect about the way positive and negative things affect one’s life. I’ve just been very lucky. I’ve worked steadily. I’ve seen promising moments loom and evaporate, and I’ve seen an awful lot of offers turn out to be some of the things that have happened to me. And also I have people around me who mock me.

Who mock you? Yes, my family and friends!

Keeping you down to earth? Oh, yes!

“To say this is a gay film is to say a film featuring an Asian person is an Asian film, or a film featuring a Jewish person is a Jewish film. A lonely man lost his lover, and that’s what we’re invited to respond to. I don’t think anyone would call it a gay film after they finish watching it.”

“Actors are promiscuous creatures… If you do film work on a regular basis, you’re employed for as little as 21 days to 3 months. You give yourself to it completely. It’s the only thing that matters. Full immersion… You come out of it and blink in the light, feel a little bit regretful for a [few] weeks, and then you’re on to something else with equal passion.”

Placing all your chips on A Single Man was a good bet. I didn’t bet on it, actually. I don’t know what it was that compelled me to do it in the end, but it had a lot of things going for it. There was nothing ordinary about it. The fact that it was Tom [Ford], who is a unique person… I didn’t know very much about him, but I had met him a couple of times. This very brilliant man who’d never made a film before had chosen this unlikely story. I knew [Christopher Isherwood’s] Berlin stuff, but I knew nothing about his L.A. life and work. That Tom had chosen me was compelling. There was nothing that resonated of the treadmill. It was just unexpected. Part of me wanted to run away from it. I had just worked a lot last year and I didn’t plan to be working those months. What got the better of me was, I couldn’t recall reading anything like it. I had to meet Tom and understand his ideas for it, [so it was] a combination of that and this extremely unconventional piece of writing. I don’t know of any other script that takes the day and the life of a man — and it’s his last day — without giving itself over to glib plot devices. It was a very economically written script. There’s a lot of time without dialogue that would depend on what I was going to bring to it, and there was a lot that would depend on what Tom was going to bring to it. So it was a leap of faith for me, but I realized that it was a huge leap of faith for him, because this was a very important project for him, it was very personal for him and he was placing it in the hands of one actor. And there is something compelling about someone else’s trust in you that makes you reciprocate that trust. So that’s what pulled me in.

How did you weigh the pros and cons of working with a first-time director best known as a fashion designer? I’ve worked with first-time directors before, and he’s not a usual first-time director. This man has extraordinary credentials. I don’t know much about the fashion world. He didn’t approach me conventionally. He wrote me an email. He must have gotten my email address from somebody. I opened up my computer, and there was Tom Ford in my inbox. It was a very elegantly written and thoughtful letter telling me what the project was about and why he felt that I was right for it and why he thought I would respond to it. I phoned my agent and asked, “Do you know about this?” And he said, “Yes. This is something you should take quite seriously. Tom is very, very particular about how he wants this done and who he wants in it.” In fact, from an agent’s point of view, he was actually impossible about it. There were quite a few people interested, but there was only a very, very short list of people he was willing to consider.

It’s such a beautiful film — not only visually, but the story is universal. What do you say to people who label this as a gay film? They’re not looking very hard if that’s what they would reduce it to. There’s nothing wrong with that as a topic, it’s just I can’t really find a label for this film. It goes back to why I wanted to do it. It’s hard to find a genre for it.

I’ve still not met anybody with whom it didn’t resonate on some level. It’s entirely to do with an experience everybody has experienced: loss. To experience anything is to experience loss. It’s about isolation, and everyone knows something about that. The fact that the man happens to be gay is completely irrelevant. Nothing depends on that fact in this story. Even the moments that seemingly draw attention to that fact, like in the phone call wherein [George is] told his lover is dead, and he won’t be invited to the funeral, that could be a guy who’s married to a woman who’s not approved by the family. What was so progressive about Isherwood’s writing was that he managed, with complete frankness, to write male characters whose love interest happened to be men without making an issue of it. He greeted it as if it was entirely acceptable [in] the mainstream. That was pretty progressive in an era when a lot of his contemporaries, like Noel Coward and Terence Rattigan, totally had to hide their sexuality. His characters have to struggle with a lot of things, but they don’t struggle with homosexuality. That’s probably one of the few things George is not having a struggle with. It addresses that issue in a wonderfully, elegantly, seamlessly other kind of way, if that makes sense. George is just like everybody.

What does that say about our society? People are people. We cannot live in a world where minorities of any kind aren’t given the same rights. I would love to be in a world where ethnicity and sexual orientation and choice of religion are not primary to how we judge them. To say this is a gay film is to say a film featuring an Asian person is an Asian film, or a film featuring a Jewish person is a Jewish film. A lonely man lost his lover, and that’s what we’re invited to respond to. I don’t think anyone would call it a gay film after they finish watching it.

You were filming A Single Man here in California the day Proposition 8 passed. What was the feeling on the set and among the talent after that happened? The actors were only me. It was a very solitary shoot a lot of the time. It was also the day that Barack Obama won the election. I would say that was the dominant news. California…I didn’t know anybody very well. We were only five days into shooting, kind of a lonely experience, really, because I had none of my own colleagues around me. It was very long hours we were working, and at night, and it was about nine o’clock in California when the winners of the general election were announced. I don’t remember when I heard Prop. 8 had passed, but it was the same day that we did the phone call where I’m told about the death of my partner and the fact that I’m not going to be invited to the funeral. How’s that for poignant?

I can’t deny that I couldn’t help reflecting on the fact that we’re in no position to patronize the past here. It’s tempting to say, “Well, gosh, things must have been tough back in 1964 with all that ignorance and bigotry.” Then a law like that goes through, and you realize in many ways we’ve made very little progress. But on the other hand, there was a highly articulate president, and an African-American president, and all sorts of things going on, which, as far as I’m concerned, were to be celebrated. But I do remember sitting in that chair about to do the scene where the phone call happens, and the sound guy took his hands off his headphones, quite powerful, and turned the volume up and played McCain’s concession speech. It was very quiet. Nobody had even asked anybody else about their political sympathies, particularly. But anyone who’s been on a film set knows you’re not going to get a lot of Republicans on a film set.

One of the memories that sticks out very clearly in my mind was, on the way to the set that day, I passed families with placards who were campaigning for Prop. 8. They were like these drunks, like George’s neighbor [in the film] across the street. They were very wholesome Southern California WASP families with their kids out. There was just something that really disturbed me about seeing children campaigning for something [that] they didn’t understand. It was pure bigotry, and obviously the children wouldn’t be understanding it that way. There’ll be all sorts of talk about “Christian values,” and “family values” and that sort of thing. That definitely did resonate, but I can’t say that I felt that those issues were at the heart of the story we were telling. Then again, you couldn’t help feeling it chiming with what we were doing.

A Single Man touches upon the ignorance that still exists, but it doesn’t beat you over the head with it. It never occurred to me when I was playing George, but you know those EPK [electronic press kit] interviews you normally do, where you have someone come to the set and do an interview, which then goes on the DVD extras? Tom did those interviews himself. One of the questions he asked me was, and this was right toward the end of filming: “Is the fact that this character is gay important to you in the way you played him?” And I realized that I almost hadn’t thought about it for the entire movie. Obviously, I hadn’t overlooked it, but I realized at that moment that it had nothing to do with how I was playing him. I had just forgot about it. I’m playing King George VI right now, and I’m not getting anybody saying, “What’s it like to play a heterosexual?” or “How do you feel about these heterosexual movies?” It ended up being the same, really.

That’s right, you’re currently filming The King’s Speech in England, in which you portray King George, a king who stutters. You’re not stuttering now though. How does one learn how to stutter for a role, anyway? I have been stuttering, actually. We had a Christmas break in which I’d mastered it. It does get into your system. By the way, I’m working with Derek Jacobi on this film — who, if you’re English and of my generation, is probably, as an actor, one of the most famous stutterers, for I, Claudius, the great BBC series. It’s probably the first performance I ever saw of somebody stuttering. He reassured me that it goes away. It happened to him, too. He found himself stuttering for a few weeks after the end of the work. You’ll lose it.

The British seem to be able to make these opulent period dramas with all the top-line talent for ridiculously economical budgets. How is that done? Well, I was thinking this a couple of days ago. I’m making a fairly small-budget film right now. We were allowed to shoot in a room that looks sumptuous and opulent. I’ve been in this situation before. People take a look at that and think it looks expensive. That was not our art direction. Those gilt frames and chandeliers were there already. We have to pay whatever it costs to shoot it in that room. So opulent period dramas aren’t [as] expensive as they look. Only once in the shooting of this film I’m doing have we even been allowed to close down a street. We actually have to shoot out of a doorway, and we are going to have to do a bit of CGI [computer-generated imagery]. We managed to get an old car to park right outside the door, and they’re going to have to CGI-out the buses and taxis that are going on past behind it, which is going to cost some money. Funny enough, I don’t know if it’s going to look opulent or not, but it’s being done on a shoestring. Actually, in this case, London is being made grimier, because everything was so black from the smoke in 1937. Buckingham Palace looked completely black. I just saw a picture the other day. Part of our difficulty is London is looking too clean; they have to grime-up some of the buildings. Top-line talent? Well, we just don’t get to do films too often. We get quite excited when a movie comes to town. There are an awful lot of actors, very talented actors, that don’t find themselves in movies that often, and people are all too keen to participate in them.

![]() re there any attributes of English filmmaking that you’d like to see American studios adopt? I don’t know how to qualify that. American filmmaking, in my experience, is not that different. I haven’t done a lot of big studio pictures, I really haven’t. Even the ones that look big afterwards, big-ish, certainly by British standards, like Bridget Jones, was not really a studio picture. It was made by Working Title and backed by Universal. But it was not a studio picture, and it featured Americans. I’ve rarely done a film without an American actress somewhere in it. Almost randomly, pick any movie I’ve been involved with. I’ve found filming in the States a very pleasant experience. I find both the crew and actors more sort of integrated with each other than in England, possibly. Again, there are a lot of exceptions to that rule, if it is a rule. I’ll tell you one thing quite simply: one thing I like about American filmmaking that I’d like to see the English adopt is decent catering. You have to be lucky to get good catering in England. The standards can be absolutely shocking. The people I’m working with now are good. It’s not to be taken for granted in the United Kingdom. The British reputation for bad food, generally, is out of date. You shouldn’t have to eat badly in England anymore. London is a big, cosmopolitan city. The idea of the lack of good cuisine is outdated, but not on a film set. Any English people who’ve worked in the States talk with misty-eyed tones. I heard everybody doing it the other day, waxing on about American craft services and the dining options.

re there any attributes of English filmmaking that you’d like to see American studios adopt? I don’t know how to qualify that. American filmmaking, in my experience, is not that different. I haven’t done a lot of big studio pictures, I really haven’t. Even the ones that look big afterwards, big-ish, certainly by British standards, like Bridget Jones, was not really a studio picture. It was made by Working Title and backed by Universal. But it was not a studio picture, and it featured Americans. I’ve rarely done a film without an American actress somewhere in it. Almost randomly, pick any movie I’ve been involved with. I’ve found filming in the States a very pleasant experience. I find both the crew and actors more sort of integrated with each other than in England, possibly. Again, there are a lot of exceptions to that rule, if it is a rule. I’ll tell you one thing quite simply: one thing I like about American filmmaking that I’d like to see the English adopt is decent catering. You have to be lucky to get good catering in England. The standards can be absolutely shocking. The people I’m working with now are good. It’s not to be taken for granted in the United Kingdom. The British reputation for bad food, generally, is out of date. You shouldn’t have to eat badly in England anymore. London is a big, cosmopolitan city. The idea of the lack of good cuisine is outdated, but not on a film set. Any English people who’ve worked in the States talk with misty-eyed tones. I heard everybody doing it the other day, waxing on about American craft services and the dining options.

These days, there’s so much dependence on the big opening weekend. How do you measure a film’s success? I don’t go around measuring it, really. When it comes to the promotional side, and how a film does, that really does feel like my day job. I do what’s expected of me, and I go home, and, of course, I hope it’s going to do well. But I leave the means by which these things are measured to others. There’s usually someone else telling me, “It’s a good thing that it’s opening this way,” “We’re measuring this one by screen average,” “We’re opening on two screens and then we’re rolling it out.” I’ve never really invested much in whether I agree with the strategy. I tend to take other people’s word for what’s good news and what isn’t. Obviously, in some cases, a film has a conventional opening, and if that film is relatively commercial, then that weekend you don’t have to know anything to know what that is about. I don’t know why it’s shaped up the way it has. I don’t have very strong feelings about it.

What’s your view of an American film industry rife with sequels and remakes? I wouldn’t count them out just because they’re sequels and remakes. We can all harmonize about the fact that that seems to speak of quality of the imagination. It’s not just that; it also has to do with fear. When we see a lot of sequels and remakes, that’s a sign people want to stick to what they know. They don’t want to take risks. They want guarantees. They want something that looks tried and tested. They want something that conforms to a formula. I understand that. If you’re putting a helluva lot of money into something, and you’re not necessarily on the creative end, then I can see how the person who’s having to write the check is saying, “It worked the first time. That’s why it’ll work the second time.” Of course, that’s never a perfect equation. It’s often catastrophic, and for very logical reasons, actually. Trying to operate that way is flawed. Films that really succeed are usually based on risk; they’re usually a step into the unknown. Probably the way in which you can misjudge things the most is to try and remake a masterpiece. It’s very difficult to think of an example of that working. If you insist on trying to mine old projects for your material, you’d probably be better off going through some of the forgotten B movies that nearly worked and that just didn’t quite.

Why not remake a second-rate movie into a good movie instead of trying to take a masterpiece and repeat the exercise? The components aren’t going to be there a second time around. It’s basically overlooking reasons why something worked the first time, and it’s very, very hard to ever quantify that. It’ll be the nuances in the acting, or it’ll be something in the chemistry between the actors — all those extraordinary, happy accidents that take place in the process of making a film that made it what it is, and you simply can’t reproduce that.

And I guess the same applies to sequels. There are sequels that take on different forms. You can’t really call the Harry Potter films sequels. There are instances where it is perfectly appropriate that there’s a series. It’s a sign of insecurity. I know that with the economic situation, and the way it’s affected Hollywood, it’s made those kind of endeavors more likely. The projects that I tend to be seeing now are that; they are either sequels, or remakes, or they are tiny, improbable projects like A Single Man, which have a private, one-stop financier behind it. You have some passionate, reckless person, and everyone does it for nothing. So there are two polar extremes.

What was your reaction when you heard Universal was keen on trying to come up with a Mamma Mia 2? I don’t really know much about it. I’ve only heard this, and usually when I’m interviewed someone else has heard it. There’s been quite a lot of talk about a Mamma Mia 2. I can only regurgitate the gossip that I’ve read in the press. I’ve read that Benny Andersson of ABBA hasn’t ruled out ABBA contributing to a sequel. I then went on the record as having said that I’d read that. I then heard that Amanda Seyfried, my good friend who was in Mamma Mia, heard that quote and had said that it’s not true, that Benny Andersson had said he was not going to contribute the music. So what I can tell you now is that my understanding is [that] Amanda Seyfried has said that I’m wrong, that Benny Andersson says that he won’t contribute ABBA music to a sequel. If that helps to clarify the situation.

What about yet another Bridget Jones? Again, I just got that filtered back. I have nothing on the inside. I’m not really in touch with the filmmakers. Not closely so. It came up in the trades. I wouldn’t be surprised if they have a go. The material is there because Helen Fielding has continued to write. Yeah, I didn’t have a huge appetite for doing Bridget 2, really. I don’t think any of us ever actively said, “Yes.” I just think we found ourselves doing it. It was awfully nice seeing everybody.

You want to do something more challenging instead of always going back to the same well? Yes. I remember Hugh Grant saying, “Doing Bridget Jones 2 was like putting on a pair of wet swimming trunks.” I know exactly what he meant. You have to take things on their own merits. I wouldn’t turn my nose up at something just because it’s a sequel. If they somehow struck new ground with a number three, it might be worth looking at. But the idea, in principle, doesn’t interest me. I’ve long said that the only way it would be appealing is to see us advanced in years and having deteriorated quite heavily. A paunchy, balding Mark Darcy [Firth’s character], and I can see [Grant’s character] Daniel Cleaver as a loose, silver-haired Lothario trying to live out his youth. It might be quite fun to see the characters in that light, but it does seem like going back, to me. I’d be much more tempted, really, by the idea of fresh pastures.

Do you miss the stage, and do you have any plans to go back and do a stage production? I’m beginning to miss it. There was some time when I didn’t feel the urge. It has more to do with what I would go back for. You tend to be looking at a long commitment and a lot of fear. If you’re going to be involved in a commitment of any real length… I just want it to be the thing that compels me to do that. So I don’t think I’ll do that just to be onstage. But I got bitten again recently in a way that surprised me. It was just a one-off last year — a memorial celebration of Harold Pinter’s life at the National Theatre, and it was a group of actors who’d worked with him. He was very much in and amongst actors. He was an actor himself. He loved actors. He loved the process, the rehearsal process, loved being a part of it all. I was directed by him in The Caretaker in 1991 — probably the best production I’ve ever been a part of, certainly one of the best. He was one of the best directors I’ve ever worked with. He was extraordinarily good. I did a piece from The Caretaker [for the memorial], and I was pretty nervous, but I was astonished at how much I loved being up there just for a few minutes. So I started looking around for something to do onstage after that, and then this film came up. I’m sure it’s gotten into my system, and I’ll be doing something onstage very soon.

![]() any actors turn to producing to have more control over their careers. Any plans to start your own production shingle? [Sigh] Producing is such a headache. I don’t know how they do it. I’m married to a producer. I know she wouldn’t wish it on anybody. In fact, she’s not sure she wants to continue to do that. She has other things that she does. It might give you control up to a point, but there are all sorts of battles that don’t interest me that much. You were asking about opening weekends and figures, and the minute I start thinking about it, I glaze over. I’m not proud of that. That sounds like, “Hey, don’t ask me, I’m an artist.” That’s not it. Actually, it’s a rather infantile and irresponsible position to take. We should get responsible and accountable as to what our contribution is and what’s going on in terms of the economic side of what we’re doing. I don’t think creative people have any right to detach themselves from that, or think less of the people that have to work that side of things.

any actors turn to producing to have more control over their careers. Any plans to start your own production shingle? [Sigh] Producing is such a headache. I don’t know how they do it. I’m married to a producer. I know she wouldn’t wish it on anybody. In fact, she’s not sure she wants to continue to do that. She has other things that she does. It might give you control up to a point, but there are all sorts of battles that don’t interest me that much. You were asking about opening weekends and figures, and the minute I start thinking about it, I glaze over. I’m not proud of that. That sounds like, “Hey, don’t ask me, I’m an artist.” That’s not it. Actually, it’s a rather infantile and irresponsible position to take. We should get responsible and accountable as to what our contribution is and what’s going on in terms of the economic side of what we’re doing. I don’t think creative people have any right to detach themselves from that, or think less of the people that have to work that side of things.

It’s the story that gets me. Then I’d probably go out and fight for it, and if that meant I had to develop it myself, then, yes, I would. In fact, there is something. I’m not going to name what it is, because it is too vague and theoretical at the moment. But I am sort of dipping a toe into that world, in terms of developing a story.

Actors are promiscuous creatures. I’ve been spoiled by the rhythm of my life as an actor. If you do film work on a regular basis, you’re employed for as little as twenty-one days, in the case of A Single Man, to, let’s say, three months. You give yourself to it completely. It’s the only thing that matters. Full immersion. You feel that the rest of the world barely exists. You come out of it and blink in the light, feel a little bit regretful for a couple of weeks, and then you’re on to something else with equal passion. And that can happen twice, three times a year. If you’re going to direct something, you have to feel committed for a lot longer than that. So you can’t have that distraction. Actors get quite addicted to the turnover. The fact that we can afford to be commitment-phobes — we give ourselves to this and move on — it’s something that makes you feel protected. I’m talking about a film that I did last year. I’m insulated by the film I’m doing now. And if nobody likes the film you did last year, you’ve moved on, so there’s a sense of protection there. You’re much more vulnerable if you’re going to develop your own project. You really do have to be exposed to whatever happens to it, and committed for a couple of years at least.

Speaking of directing, any aspirations to step behind the camera one day? Yes, I’m beginning to feel I might be more inclined to do that. No, I haven’t spent my life thinking what I really want to do is direct. A lot of that feels like too much hard work. There are aspects of directing that appeal to me, and other aspects that appeal to me a lot less. A great director has to have a multitude of talents. It’s hard to imagine that the perfect director could even exist. To be a brilliant film director, really, you have to understand people very well. You have to know how to inspire them. You also have to have a vision, and you have to have the necessary skills in communicating that vision and encouraging the people to want to share it and understand it. You also then have to know about text, and understand the power and limitations of text. You have to understand the whole visual grammar of cinema. You have to know editing. You have to understand lenses and lights and what lenses can do for you.You have to know how to operate the business side of things. The list goes on and on and on. If you checked three of those boxes, you’re probably pretty good, because most directors can’t have equal skills in all of those departments. I know some brilliant directors who haven’t really got a clue which lens is which. They have someone to tell them about that. Also, there are a lot of effective directors who don’t really understand how to get the best out of actors. Tom Ford, for a first-timer, he covered a lot of it. He really has the abilities in a lot of those areas that I just described. The things he didn’t know yet, because he was on his first film set, he learned on the job.

You’re a published author. What about a script? Do you have one in you? A story you want to tell? I don’t know if I have one in me. I have a couple lying in drawers. [Laughs] They came out of me, but they didn’t get very far. I’ve got a lot of scrappy unfinished stuff. I scribble away pretty much as a hobby. I’ve done that all my life, pretty much since I could write. I don’t know why I’ve never really pursued that, or pushed it out there. It could be a discipline. It could be I don’t feel like I’m good enough to really try to get to the end of things. To really see that kind of work through, you have to embark on a very solitary journey.

It’s very personal. Well, it is very personal, but again, as I’ve said, I’ve been very spoiled by the quick turnover pace of the work I do. I’ve also probably been inspired by the collaborative nature of what I do. I enjoy that. I work with people. I bounce off people. I get inspired by collaboration, and writing is solitary. I’ve done it. I’ve sat there. And I’ve been solitary. I love being alone, up to a point. Actually, I love being alone for indefinite periods of time. But when it comes to what gets the best out of me creatively, I tend to find that’s with people, not staring out a window.

So your stories are just sitting in a drawer, never to see the light of day? I pulled one out of a drawer and had it published a few years ago. Nick Hornby made me do it. Having become friends, Nick said he was fairly sure I could be a writer, so it was worth finding a way to encourage me to do it. And when he put together a collection for the Treehouse Foundation, for autistic children, he got a bunch of his friends together to contribute. He said he wanted a monologue of this many pages. We shook hands and he said, “You’ve got six months,” which no one could claim you didn’t have time to come up with anything. I actually embarked upon something that was disastrous. It was really awful. I reached too far for something that was completely out of my depth, and then basically I just grabbed something out of the drawer. There wasn’t much of it yet, but it was the seed of an idea, and I wrote it up in a couple of weeks. If someone made me do it again, I’d find some bits of paper in the drawer and do something with them, perhaps. I don’t know. But I’ve never done enough with it to say it’s amounted to a serious enterprise. I enjoy doing it, though.

How many more years do you want to be doing this? Taking into consideration your strong social sense, are there times when you think your efforts might be better served in the service of others, or do you see them going hand in hand? One of the reasons I’ve set up Brightwide.com is I’ve been doing campaign work for years, and I’ve been acting for years. And I find myself in situations where I wouldn’t be asked if not for the fact that I have some kind of profile, which comes from being an actor. Obviously, there’s going to be a perpetual paradox about it, because who the hell wants to hear from an actor on any serious subject? But nevertheless, that’s how it works. So I find myself having to bluff in front of the Secretary of the World Trade Organization, or making speeches to the European Commission, which is the result of a very brief, intensive period of homework. This is stuff I care about. And I have as much right to speak as anybody else as a consumer. If anybody doesn’t want to listen to me, they can switch me off. But I have a big mouth, and that’s it.

With Brightwide, it’s a chance for me to bring the two worlds together. It’s a forum that exists online but is very much offline as well. I sort of see it as an ongoing film festival, really, for social/political cinema. The kind of films that are likely to provoke forum debate — or hopefully, even better, action. The idea is to create a library of films that you can watch online, and you can also watch at events that we will organize. You have a library of films that ignite passion. This is based on experiences at film festivals, seeing films that produce a passionate reaction in an audience, you get a Q&A and especially the younger people ask, “What do we do?” “Where do we go?” “Where do we march?” “What do we sign?” “Who do we write to?” “Where do we join?” All too often there are no adequate answers to those questions. So here it’s a chance, hopefully, for film, and the power that it has, to not only ignite that kind of passion, but also to give it somewhere to go. We have formalized links with some of the major NGOs [nongovernmental organizations]. So if you watch a film about women’s rights in Liberia, you will be given the chance to then, in those ten, twenty minutes when you’re feeling pretty raw from having watched the film, you’ll be guided to people who are active in dealing with subjects like that. You can join organizations, find out what events are taking place and hear what other people have to say about it, and also see what other films relate to that. Working with organizations like Oxfam and Amnesty [International], you see them trying so hard to get that kind of passion going. I’ve seen T-shirts and slogans and posters coming and going. Some of them have some success, and some of them have short-lived success and quite a lot of them have none whatsoever. It’s rare they’re able to use film as an instrument.

![]() hat’s a brilliant idea. Oftentimes, audiences do ask those questions, and want to know what they can do, but then they leave the theatre and go back to their lives, and even though the film affected them, they tend to forget. It’s such a waste. It’s such a waste to see it dissipate like that. At the same time, you have all these people with something to say trying to harness, trying to get some of that passion, and the two just don’t meet often enough.

hat’s a brilliant idea. Oftentimes, audiences do ask those questions, and want to know what they can do, but then they leave the theatre and go back to their lives, and even though the film affected them, they tend to forget. It’s such a waste. It’s such a waste to see it dissipate like that. At the same time, you have all these people with something to say trying to harness, trying to get some of that passion, and the two just don’t meet often enough.

We’re still in the beta stage at the moment, but we’re about to launch the full version. But we launched in collaboration with the London Film Festival with a brilliant film, No One Knows About Persian Cats, which is about a real rock band — the musicians actually played themselves in the film that’s more or less about their own lives in Tehran. These are young kids who don’t really want to be political at all, but the very fact that they are musicians makes them political because of the laws in that country governing those things. A woman is not allowed to sing at all unless she has her head covered, and there are three of them singing. They were constantly arrested for the kind of music they were playing. The two main actors have claimed asylum in Britain now, as a result of the movie. We screened that film, and we had the actors and the director and a music journalist, a political journalist who’s an expert on Tehran, involved in a discussion afterwards and we got some pretty heated stuff going with the audience as well. We had representatives from Amnesty and one or two of the other NGOs, as well. It was everything I was hoping for. It seemed to make sense.

Brightwide is a place where it doesn’t have to end with the credits rolling on the movie. The conversation continues beyond that. And actually you take part in that story onward. You continue it. That’s where the interests I’ve had politically over the years, and the interests I’ve had in cinema, are hopefully converging.

Is there a side of you we haven t seen yet? Would you be open to doing action films, for instance? I don’t find them that interesting, and I’m getting a little old.

That’s all in your head, Colin. [Laughs] No. Believe me [laughs], it’s just the rest of me to deal with, and I don’t really want to spend that long in a gym, frankly. I don’t know… All the running around and explosions. No. I don’t think so. I don’t see that [happening].