he psychological Atlas of America that has been charted by Academy Award winning filmmaker Alexander Payne is so movingly enlarged in Nebraska that its Oscar nominations in six categories come as no surprise, nor do the awards it has already garnered from critics groups, especially for its star, Bruce Dern. Each of Payne’s five previous features — Citizen Ruth, Election, About Schmidt, Sideways and The Descendants — manages — at times in startling ways — to be a fresh departure in conflict and theme from the others, yet at the same time, they are uniquely continuous in vision and tone. Although he works with a variety of source texts and partners (most often of all with longtime co-writer Jim Taylor), his films bear a distinct individual stamp. Each new one seems like the work of a novelist mining a highly personal territory. Even Payne’s fifty-minute UCLA thesis film, The Passion of Martin, made in 1991, is so confident in its humor and emotional honesty that it predicts, and keeps company with, his later work.

“A film has to answer two questions for me,” he told Fade In when we first sat down with him in 2000. “What does it mean to be human, and what is a film?” He has repeatedly answered the first question by being a close observer of people. In terms of defining what a film is, he has stood his ground in terms of telling exactly the stories he means to tell, refusing time and again to be pressured about casting, pace or even color scheme — as one can see in the silvery black and white of Nebraska, shot by Phedon Papamichael.

Payne studied at Stanford and the University of Salamanca in Spain before enrolling in the graduate film program at UCLA. Filmmaking emerged as an ambition after he majored in literature and history as an undergrad and seriously considered a career as an investigative journalist. Movies in themselves had been a source of passionate enthusiasm since early boyhood, but the desire to make them grew late. This worldly, classical background has served Payne well. As a working director, he’s interested in the authentic — and brings chops to his stories that grow out of experience rather than fantasy. In person, especially against a Hollywood backdrop, he cuts a figure of impressive urbanity — whip-smart, dryly witty.

Our talk in 2000 took place in the first flush of his breakthrough success with Election. At that time — with opportunities and risks rearing up all around him — Payne spoke of his deep admiration for such master filmmakers as Kurosawa and Buñuel, and was optimistic about his own chances — indeed, those of any sufficiently dedicated American filmmaker at that moment — to build a solid body of work along just as prodigious personal lines. Nebraska argues that he’s kept this faith with himself, as well as his creative enthusiasm.

Yet for all its comedy, there is a mournful spirit haunting the film, too — perhaps driving it. That’s what we sought to ask him about when we caught up with him in the thick of this awards season. There is, in this new picture, a reflective, nostalgic pang that works like an undertow beneath its almost farcical premise of Woody Grant, an old man (Dern) so deluded by the be-a-millionaire pitch in a piece of junk mail that he not only embarks on a fool’s errand worthy of Don Quixote, he dragoons his long-suffering son, David (Will Forte), into coming along as his knightly sidekick.

Payne has done road movies before — About Schmidt and Sideways prove he has a natural facility for them — and he’s a whiz at depicting families, for intimate rivalries and high dysfunction operate in all his films, especially in his contemporary island saga The Descendants. He is himself the descendant of several generations of Greeks active in the growth of Omaha, Nebraska, so his sensitivities in these matters have deep roots.

Maybe that’s why most of Payne’s films are set in Nebraska — he grew up there. He maintains a home there, as well as in Los Angeles, and given that he has manifested exactly the humanistic films he set out to make a decade and a half ago, this seemed like an ideal moment to catch up on all things Nebraska and also draw him out about where he sees himself here and now on the heels of his fifty-third birthday.

You just had a birthday — happy belated. Thanks.

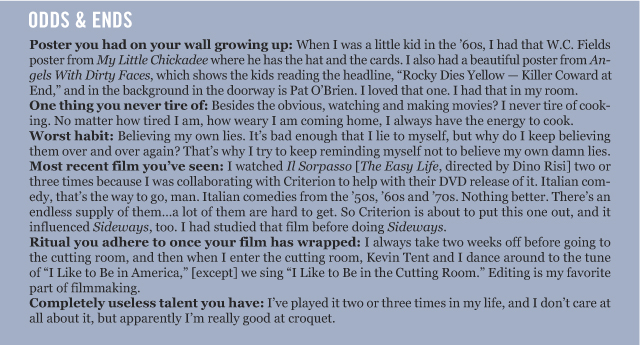

How did you spend your day? Or are you one of those people who just want to get it over with? [Laughs] That’s a funny question. Actually the birthday was one Hollywood party obligation day. It’s the Oscar nominee luncheon, so I flew to Los Angeles in the morning, attended the luncheon, ran a couple errands in the afternoon, had a birthday dinner that evening with my editor, Kevin Tent, whose wife’s birthday is February 10th, and also with Laura Dern, whose birthday is February 10th. We have a birthday club. And my editor’s birthday is February 7th. We all go way back. Then I flew back to Omaha Tuesday morning.

You’re currently living in Omaha. How’s that downtime working out for you? It’s not exactly downtime. I’m working on a new screenplay. The good part of knowing that I don’t have a chance at winning the best directing Oscar is that I can get back to work. They’re not as on my tail to appear at all those events. So I’m working again with Jim Taylor. He lives in New York, and I live between Omaha and Los Angeles. We have a system whereby we spend ten days in New York, and then have about six days off, and then ten days in either Omaha or Los Angeles, and then another six days off. We go back and forth. I’m currently in Omaha.

“I’m attracted to the idea of making documentaries at some point, in the near future. Sometimes I tire when having to spoon feed dialogue to actors and then edit them to make it seem real…[With a documentary], you have no hair stylist, no costumes, everyone knows his or her dialogue, they can only say it once and it’s real.”

“The biggest thing for a director to fear is lower quality in older age. Very few directors continue to make vital and excellent films into old age…Lina Wertmüller said an artist can lose many things over the years but never anger. And Buñuel stayed angry.”

Would you say it’s easier to work on projects there? It’s just the benefit of living in a provincial city. It will sound cliché to say, but it has a dramatic importance on one’s daily life. The same errands that take two-and-a-half hours in Los Angeles take me under an hour here, and you can drop in an unforeseen errand. More of your time is your own. It’s just quieter.

Well, you’ve had a bit of hindsight now. What did you take away from your experience working on Nebraska? It’s a modest film. I aspired for the film technique to be simple and elegant. A lot of that was what the austere screenplay called for in the first place, and a lot of it was that I only had thirty-six days in which to shoot it. So I needed to be very exact with camera placement. If I only have one chance to make a black-and-white film, I wanted to knock people’s socks off. That was the challenge, and it just made me and the DP be very exact with what we were doing. There were other films — The Descendants has a little more Sturm und Drang to it, and the next film I want to do I want to let loose and have a more energetic film style. This one is quite staid.

Nebraska had that ten-year gestation period. Do you think it would have been a different film had you made it ten years ago, or that you brought something extra to it directing it now? The one thing that I was conscious of was that, I had almost ten more years’ experience taking care of my aging parents. So Will Forte’s character’s actions are informed by my experience. I can relate to that very much. Outside of me, the fact that the economy crashed, and that shows up in the film. The film becomes a little more of a Depression-era film. I always wanted to make the film in black and white anyway, but the fact that we were making it now made it feel more Depression-era. Many of those small towns are not at their zenith as they used to be. But even more so now. So it was fun to be making the film now, and to capture a sense of that.

There’s a color version of Nebraska that exists. But you have no plans to ever let that see the light of day — or do you? No. That’s meant for Arte Laos or Channel 4 Moldova — those TV outlets that specify absolutely only color. As part of my convincing Paramount to fund a film in black and white, [as] they harped about the TV output deals, I said, “I’ll provide you the color version for those TV output deals, very specific ones, but contractually it must be black and white for theatrical, DVD and streaming.” But I saw the color version once. I liked it. It was really pretty. Some shots look even prettier in color. We made it look like a color from about 1970-’71, like the colors in Five Easy Pieces, for example. But it’s not right for the film.

The strategy is something that John Boorman also applied to The General. He said he didn’t want to make poverty look pretty, because color will do that. It’s just a sensible artistic choice. The black and white in Nebraska is beautiful. Thank you. It’s the first Oscar nomination that [cinematographer] Phedon Papamichael has received, and it’s for precisely this film.

You’ve undoubtedly been asked hundreds of questions by now about the film. Is there one question that you always thought should have been asked of you, but hasn’t yet? Not really. This is not necessarily a question, but an observation. In critiques, or within questions, I’ll hear, “Oh, the film is so somber.” “Yes, it’s funny, but it’s such a bleak portrait.” And “Sometimes maybe it even teeters on making fun of those people.” Like there’s a lot of bleakness and misanthropy in the film, when, in fact, all I see is kindness. The film builds to a moment of an act of kindness from the son to the father, like we all do, perhaps; [we] try to give our aging parents, or our aging friends in general, help to retain shreds of their dignity. I don’t get too many questions about that.

“Why does everything now adult have to be absolutely shrink-wrapped and be robbed of the production value it could have? Where is Trading Places today? Where is Groundhog Day today? Intelligent, summer comedies. Where are the intelligent ones?”

You might be getting those responses from people who have not yet had to go through this type of experience with their parents. You really did create a sense of compassion, and you also created a fear for Woody’s mortality. There’s a certain point of tension where you’re not sure, as a filmgoer, whether the film is going to explore the inescapability of death. Was that ever a possibility, or were you set on staying true to the script’s original ending? No one else may see this in the film, but one perspective from which I approached it was; it’s an old man fixing to die and wanting to go over the mountain and say, “I’m going alone.” And the son, in essence, says, “Let me help you. Let me take you there.” There’s even some dialogue: “I’m not staying there. I’m your son. I can’t let you go.” Those things. Vaguely relevant. Not to put too much “heaviosity” in a nice little movie. They were elements that were relevant of the man. Yes, he’s addled, an alcoholic, slightly demented, but also, all of that is informed by impending death. I never thought he should die in the film, because it’s a comedy, but death is a strong theme in it.

You don’t feel misdirected by it all. [Spoiler] The scene where he is driving down the street does evoke the possibility, and the urgency for the son, by the textures you created — shooting in black and white and the music. Even the ending of the film, with that drive down the street, is about death. It’s kind of oneiric. It’s like what you’d want to happen right before you die. You go through the place where you were conceived and born, and you wave goodbye to public acclaim, to the forces that opposed you and to the love that you never had — that you had and perhaps didn’t have. It wasn’t exactly intended to be literal. It looks literal, but for me, personally, it wasn’t. And that was also about death.

Violence seems to be an element you avoid in the projects you choose. Why? Uh…well, how violent were Jean Renoir films? [Laughs] I like comedies. I make comedies. I’m not a violence director. Yet I like westerns, too. I’d like to move into that genre at some point.

But you love tragedies like Godfather II. Certainly those types of films are in the radius of your imagination. So it’s interesting that you’ve chosen not to go there, unless maybe they’re ahead with a western. Could be, but I don’t like violence for violence’s sake, just because it’s cool to do. However, I love Peckinpah. I love Kurosawa. I love Anthony Mann. I have nothing against anything when well done, but we have too much violence in our cinema in general. I’m sorry to be parroting a cliché.

By the way, I was watching this year’s Oscar-nominated documentary shorts, which I cannot recommend highly enough, and I walked away thinking that feature films try to show examples of hatred and documentaries try to show examples of love in the subjects that they pick. You know who said that, too, is Albert Maysles. I heard him speak one time. He said, “I go to the movies, and all I see is violence and examples of hatred, but I look around me, and I realize that all I see are examples of love.” And he [asked], “Why aren’t we showing those?” There’s something easy and facile in how it’s used in today’s cinema. But anyway, my basic answer is, I make comedies.

Speaking strictly as a keeper of the future of cinema, how do you see the future of cinema? What do you mean, keeper of cinema?

This is going off something tongue-in-cheek that you said years ago. You were speaking of your generation of filmmakers — Wes Anderson, David O. Russell, Paul Thomas Anderson — and declared you were one of the keepers of the future of cinema. More like keeper of the flame. It sure is encouraging that David Russell’s movie [American Hustle] is going to make $200 million. There’s somebody from my generation that has gone about it the old-fashioned way. Put glamorous movie stars in there, telling an intelligent, delightful story and telling it with panache and making a ton of money on it. Also, that the studio spent 40 or 50 [million], or whatever they spent on it. That’s the world that I want to live in.

“We’re in a golden age of television. I’m so happy that all that exists, but I still believe in movies. I still believe in a two-hour narrative form. Would Godfather and Godfather II have been great at fifty hours on television? I’m sure they would have been but they’re also great at six hours while still having the scope and that economy.”

Some studio people asked me out to lunch a couple of months ago, and they said, “Look, if we let you run the studio, what changes would you make?” I said, “Well, thanks for asking. I believe in the $25-45 million adult comedy and adult drama. Why does everything now adult have to be absolutely shrink-wrapped and be robbed of the production value it could have? Where is Trading Places today? Where is Groundhog Day today? Intelligent, summer comedies. Where are the intelligent ones?” Then the studio guy said, “Well $45 million, I think I might disagree with your price point.” I said, “You might, but where is Out of Africa today? Why don’t we have films like that?”

What do you worry about the most, though, in relation to film and where it’s headed? Oh, I don’t know. Just this widening chasm between — what the Europeans already called [in a French accent] “The Blockbuster!” and anything adult, which is now called “independent,” a term I can’t stand. I worry that this gap continues to widen, and about the exodus of quality writers from our cinema to television. We’re in a golden age of television. I’m so happy that all that exists, but I still believe in movies. I still believe in a two-hour narrative form. Would Godfather and Godfather II have been great at fifty hours on television? I’m sure they would have been, but they’re also great at six hours, while still having that scope and that economy. I believe in movies. We’ve had a pretty encouraging year. People say, “Oh, it’s been like a new 1939, this 2013.” I may not go that far. There have been some excellent films this year — not just American films, but around the world.

Your company with Jim Taylor and Jim Burke, Ad Hominem, has produced some pretty terrific films, like Cedar Rapids, The Savages, and you have several interesting projects in the pipeline. What was your goal in first forming the company, and where do you want to take it? Ad Hominem serves foremost as an umbrella producing company for Jim Taylor and me as writers, and me as a director. In exchange for a first look at anything we’d like to do, Fox Searchlight provides us an office and staff, headed by producing partner Jim Burke, who reads scripts, finds material and gives us any support we need. We are also, in the case of The Descendants, able to serve as our own producers.

Burke has a couple of TV [projects] that he’s trying to stir up and gain traction on, but I’m not actively involved in those. I only think about features. So I have to remain hopeful. Look, I just got $13.5 million to make a studio film in black and white, with no major stars, so how can I be discouraged?

You’re set to produce and direct Ruth Prawer Jhabvala’s story “The Judge’s Will” for Fox Searchlight. Where is that on your development slate? It’s currently residing comfortably in aspic. I thought it was a terrific story. It takes place in India. I don’t know from India, so I would relocate its story here. I don’t want to make it next. I have something else in mind, but I’m very eager to do that story.

“Downsizing” sounds like a straight comedy. Might this be your next project? On the record, it’s a sprawling science-fiction comedy or satire I want to return to quite soon.

What about heading into new territory — away from Omaha, away from, dare we say it, comedy? I don’t know. I know I want to do it. I’m now in my early fifties, and these first six features are fine enough, but I consider them just learning experiences. I hope to make one really good film. One that I think is really good. I just don’t know what that is yet. Maybe you don’t know it until after you’ve made it.

That’s so in line with Kurosawa’s remark when he accepted his Lifetime Achievement Award. “I’ve made thirty features. I’m eighty-five years old. I know less and less what a feature film is.” It sounds like, “Oh, gee, Mr. Huge Ego eating the little humble pie for show,” but I know what he means.

In 2000, you told Fade In that you also wanted to make a love story — No, I don’t.

— that you had an idea for one, but just needed more life experience. Well, actually, the one I am working on now has a bit of an oddball love story in it. We’ll see if this will be my next film. That’s interesting that I said that. Yeah, I hope I…I don’t know. I never feel old enough for anything, but you just have to do it.

“I’m working on a new screenplay. The good part of knowing that I don’t have a chance at winning the best directing Oscar is that I can get back to work. They’re not as on my tail to appear at all those events. So I’m working again with Jim Taylor.”

“[Nebraska] builds to a moment of an act of kindness from the son to the father, like we all do perhaps; [we] try to give our aging parents, or our aging friends in general, help to retrain shreds of their dignity.”

What kind of pressure, if any, are you feeling, now that you’re in your fifties, to step up the pace in order to churn out more work? I would love to be making one every year and a half. I’d be constantly swinging from film to film like a monkey from branch to branch. Ideas don’t come to me as quickly as they do to Woody Allen — or if they do, I’m not as confident about them as ostensibly he is. Nor do I wish to live with that day-in and day-out discipline of, “Every day I have my corn flakes at 8:15, I write from nine to twelve, I have my lunch, then I go to the cutting room, then at six I play my clarinet.” I can’t live like that. I like to travel. I like to noodle and read and be lazy and work hard. I don’t know. It’s usually the screenplay that slows me down. That’s why I was able to go very quickly from Descendants to Nebraska; I had the screenplay ready, and why I went very quickly from About Schmidt to Sideways. Those were in fairly quick succession. Then there was a gap between Sideways and The Descendants. Jim and I were working on “Downsizing” all that time, a difficult screenplay.

In your admiration for Kurosawa and Buñuel, what lessons have you drawn from studying the shapes of their careers? Everyone’s example is different. The biggest thing for a director to fear is lower quality in older age. Very few directors continue to make vital and excellent films into old age. But Buñuel is one. All of his films were basically very good, and his last one, at age seventy-seven, That Obscure Object of Desire, is one of his best. Lina Wertmüller said an artist can lose many things over the years, but never anger. And Buñuel stayed angry.

Are you angry? If so, about what? Yes, and I agree with Buñuel saying that while he was loath ever to declare any “theme” of any of his films, he did concede that “we do not live in the best of all possible worlds.” You could say the same, thematically, about much of Kubrick’s work. While not comparing myself to those great directors, I feel a kinship with that overall point of view. Man is his own worst enemy, but it doesn’t have to be that way.

Directing involves so much physical stamina. You’re raising an army and invading an imaginary country, in a sense. It involves so much, and yet you are so dedicated to it. Will you be like Kurosawa: nearly blind, in your eighties, directing films? Or do you have other aspirations, as well? There are a couple of other things that I’d like to do. When I finish a movie, I have two thoughts: one is, “I can’t wait to make the next one,” and the other one is, “Don’t anyone ever mention the word ‘movie’ to me again.” There have to be other things to do.

Even within film, I’m attracted to the idea of making documentaries at some point, in the near future. Sometimes I tire when having to spoon feed dialogue to actors and then edit them to make it seem real. [With a documentary], you have no hair stylist, no costumes, everyone knows his or her dialogue, they can only say it once, and it’s real. It’s the reality that we strive so desperately to replicate in feature films. That’s very attractive.

That would draw deeply on your original aspirations to be a journalist. Yes, I agree. However, Kurosawa used to say that he would like to die on the set; be carted off the set. I would rather be carted off the mix stage, knowing the film’s done.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_basic_grid post_type=”portfolios” max_items=”1″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1459302831850-054005c0-c511-8″ taxonomies=”65″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_basic_grid post_type=”portfolios” max_items=”1″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1459302831850-054005c0-c511-8″ taxonomies=”65″][/vc_column][/vc_row]