aybe it’s because he’s in Los Angeles, where food prudes abound, but during an interview over dinner at a sleek downtown cucina, Adrien Brody, who has been chatting away amiably, suddenly grows sheepish when his meal, a tasty-looking chicken dish, arrives.

aybe it’s because he’s in Los Angeles, where food prudes abound, but during an interview over dinner at a sleek downtown cucina, Adrien Brody, who has been chatting away amiably, suddenly grows sheepish when his meal, a tasty-looking chicken dish, arrives.

“Sorry it has a face on it,” he says. “I’ve tried. I was vegan for a while.”

It’s a brief but disarming moment — funny, endearing and vulnerable all at once. The notion that ordering a nonvegetarian meal is occasion for an apology might also suggest ample stores of insecurity and guilt. But in this case, dime-store psychology has about a nickel’s worth of credence. The truth is, Brody isn’t a bundle of anxiety, he’s just an extremely sensitive guy who feels things deeply — whether they happen to him, or to other people.

As he puts it, “I’ve never been able to suppress my conscience and my empathy, to a certain degree.”

It’s not an admission most actors would be comfortable sharing with a journalist, but Brody, who will soon be seen in four very different films, isn’t like most actors. Indeed, even though he’s here to talk about his upcoming projects, his conversation is refreshingly free of canned promo-speak. Instead, he is by turns earnest, excited, intense and, at times, conspicuously evasive.

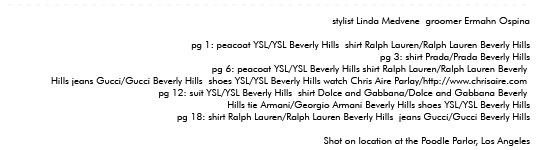

This ability to access his emotions so readily may be Brody’s greatest strength as an actor, and it has shaped his most memorable performances, from his charismatic delinquent in Steven Soderbergh’s King of the Hill to his bisexual punk in Spike Lee’s Summer of Sam to his Oscar-winning triumph as Wladyslaw Szpilman, the Polish composer in hiding from the Nazis in Roman Polanski’s The Pianist — for which he not only became the youngest person to ever win the Best Actor Oscar, but the only American actor to win France’s equivalent of the Oscar, the César.

Drawn to the arts at an early age, the native New Yorker was encouraged to explore his creativity by his father, history professor Elliot Brody, and especially by his mother, Sylvia Plachy, a photojournalist whose work often appeared in The Village Voice. He began acting as a child and by his teens was working professionally.

He went on to appear in several well-reviewed but little-seen indies, with an occasional flirtation with the mainstream in films like Terrence Malick’s The Thin Red Line and Barry Levinson’s Liberty Heights. But it wasn’t until his breakthrough in The Pianist that he acquired a public profile — thanks not only to his shattering performance, but also to the indelible image of him planting a kiss on a startled Halle Berry when he took the stage at the Kodak Theatre to accept his Oscar.

As with so many Oscar winners, that night was a before-and-after experience for Brody. Prior to taking home the gold, he was a semi-familiar face to regular moviegoers, but not a “celebrity” in the larger realm of entertainment media, where a photo of him putting coins in a parking meter suddenly had market currency. But after scoring the gold statuette, Brody had to get used to being watched whenever he left the house — not only by the paparazzi who suddenly began trailing him, but by passersby doing double takes at the sight of that guy who won the Oscar.

It was an adjustment for Brody, whose avid people-watching had always fed his craft. But in the years since, he has grown to accept the occasional annoyance that comes with a loss of privacy, preferring to focus on the many advantages of fame — especially the access to compelling material.

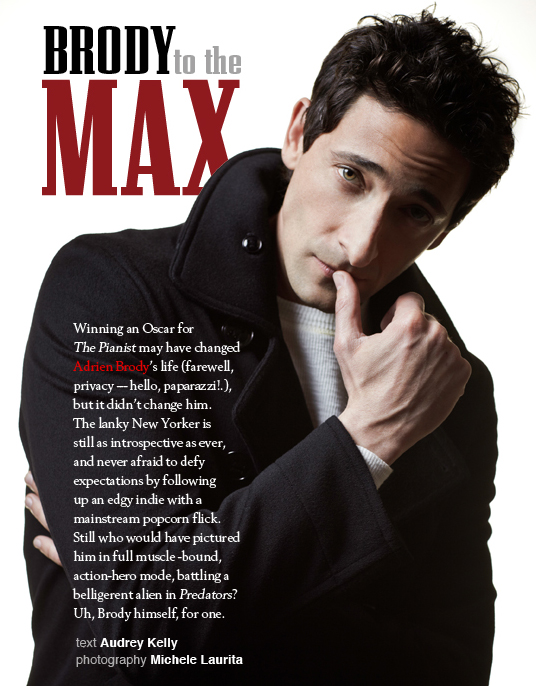

Since The Pianist, he has remained true to his art-house roots with films like The Jacket, The Darjeeling Limited and Manolete, while making multiplex headway with larger-scale productions like M. Night Shyamalan’s The Village and, especially, Peter Jackson’s King Kong. This summer he takes on a new challenge in his first outing as a full-tilt action star in Predators.

It’s an updating of the 1987 fanboy favorite Predator, which starred Arnold Schwarzenegger as an elite soldier who discovers that he and his team are being hunted by a bloodthirsty extraterrestrial. Although it may seem like a departure, Brody, who still remembers the adrenalin rush when he saw the original as a kid in Queens, had such a great time making it that he’s eager to tackle another action pic.

Also this summer, Brody will be seen in the genetic-manipulation thriller Splice, followed later in the year by the psychological drama The Experiment and, in something of a departure for a guy known primarily for dark material, the stoner comedy High School. If there’s no evident through-line among the projects, that’s because — no doubt to the dismay of his representatives — he doesn’t make choices based on salary or career advancement.

“If the material speaks to me, and it’s exciting and different,” he says, “then I’m game.”

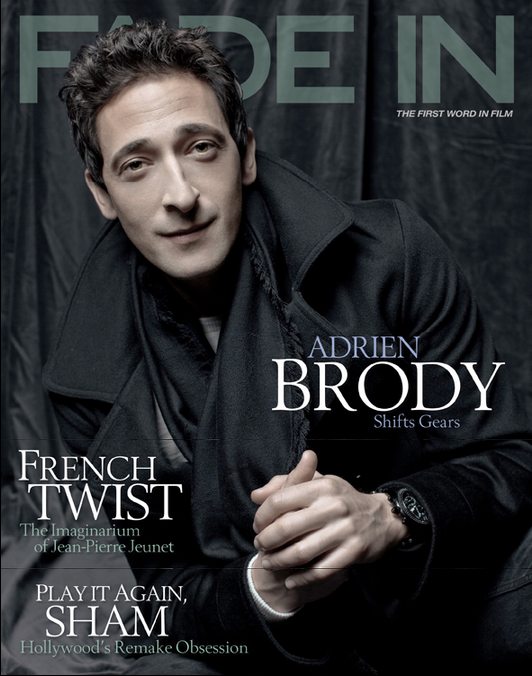

You have two studio films coming out, back-to-back: Splice June 4th and Predators July 9th. You don’t take very many breaks in between films do you? I do and I don’t. I work when I find inspirational work, and I tend to push myself when the opportunity is there because the opportunity isn’t there all the time. I took about six or eight months off for the last year. I worked on my house. I took a break, and then lately I found three amazing roles for me that were all very different and challenging that I did back-to-back — literally — and now I’m off. I have a press schedule, but that’s fine. That comes with it. There’s an emotional exhaustion that comes from working on one movie, let alone three that are vastly different that require immense physical changes and completely different emotional states. One was a pacifist who turns violent. The other one is a completely emotionless, hardened military mind, which has to be done truthfully. And another one is a man in search of his identity who is completely helpless, completely vulnerable and exposed, and doesn’t know who he is. They’re all fascinating things to explore, they’re all incredible, but they’re exhausting.

How do you transform yourself that fast from one project to the other? Well, I gained a tremendous amount of muscle for Predators. I lost weight and got wiry for The Experiment, which is a film I just did with Forest Whitaker prior to Predators. It’s based on a [German] film called Das Experiment. It’s about a sociological experiment set in a state prison-like environment. They lose their rights, and some will become prison guards and some will become inmates, and they assume their roles. They take on the roles that they’ve been given, and all hell breaks loose, and it’s pretty powerful. For that I lost weight and changed my habits, and then had to immediately cram on a lot of weight; I put on over twenty pounds for Predators.

By doing? A complete regimen. Six days of not straying one bit. No alcohol, no sugar.

I heard no sex. No sex. Nothing. [Just] training, physical weights, plus shooting a movie simultaneously also for months.

“The younger you are, the more complicated fame is… Even though I’ve had plenty of ups and downs, I didn’t have the maturity and the sense of self-awareness to have gotten me through it as positively as I did if I had been in my early twenties. You have a tremendous amount of attention: All the girls think you’re beautiful all of a sudden, and people wanna be your friends… You now emanate some sort of light that you didn’t have before, but it’s too much.”

How did that affect you? [It affected] everything. It gave me a level of confidence that I don’t really possess. Not having sex does not give you confidence. That was beside the point. That was truthful, but it was an offhand comment. That’s the thing about print: things have more resonance than they [should] when I say it, because it was like an offhand comment. But it’s part of it, and the reality of the guy is that he’s recently out of combat into a new, highly dangerous, highly stressful, completely foreign situation where he’s under attack and constantly alert and exhausted and deprived of nutrition and has to use everything. What was most important to me was to connect to an inner strength that I feel isn’t necessarily represented, or isn’t what Hollywood traditionally has seen as a depiction of a strong man. There’s a physical strength that supersedes the inner quality that really makes you a leader, and that will allow you to be victorious over an attacker that has superior strength, even to someone who is physically imposing. So that was key to me. The physical growth that I put on was partly my own sense of humor, because I feel like it’s so unexpected of me, and I could easily have just put on some weight, not necessarily been ripped. But I felt that it is something that is expected of those movies, but not of me, and I can give both to an audience, and it’s a surprise for them and it’s worth the work on my part to do that.

Most of the fanboys were surprised when you were cast. But when a teaser was shown in Austin recently, the fanboys went wild. It’s pretty amazing. I’m a huge fan of the original movie anyway. I saw that movie as a kid, front row with my boys. I remember the theatre in Queens where I saw that movie, and then to be cast in this…it’s an honor, actually. It’s funny that people would never presume, nor would I, that I would have an opportunity to play a character like that and do it justice. I feel that it’s not just a matter of getting an opportunity.

I don’t want to be given an opportunity for the sake of having an opportunity and blowing it. If you look at the work that I’ve done, I’m trying to find things that are challenging and somewhat difficult for me.

Why did you say yes to Splice? Splice was such a strange and twisted movie, and frightening conceptually. We live in a world where that [genetic manipulation] is essentially a reality. With scientific research now, they’re able to do many really strange things. Who knows what’s happening behind closed doors with private funding and the level of understanding with genetic research. It’s easy to make a chimera [an organism that has two or more different groups of genetically distinct cells that originated in different zygotes]; they make chimeras already. They’re just not integrating human DNA. But if they were able to, it’s all very possible, and I like that. There’s something special about having something be frightening on a real level. The movie is entertaining. I like the genre; I like a scary movie.

Given the film’s subject matter, what are your thoughts on stem cell research and ethics and implications of genetic manipulation? I’m respectful of peoples’ beliefs and their concerns, and I don’t think that that’s what the film is about anyway.

The film does make one think about how far we should go. The problem is that for all the horror that exists in scientific research, there’ve been tremendous positive benefits for health.

You have made a lot of interesting choices. How do you determine what type of film/character to do next? It’s not like I have to do a comedy next, because I haven’t done a broad comedy in a while. I’m very open-minded because I see the possibility of growth in all of those experiences. If the material speaks to me, and it’s exciting and different, then I’m game. If I want to do a socially relevant drama — but they’re not making that many great dramas right now, and you don’t want to a mediocre drama. You don’t want to do something that’s sentimental, so you have to find something with the director and the writing that speaks to you, with a cast that you want to go on that journey with, and then, if that option doesn’t come, you have to find other things. And I’m incredibly excited about the way Predators turned out. I’m over the moon about it.

So will we be seeing you as more of an action star? It doesn’t mean that I possibly would exclusively do that; but I would be open to things that were the right type of iconic, contemporary leading man in a movie that is entertaining. There’s something really fun about the process of making a movie like that. King Kong was an amazing process. It was long, but it was an amazing journey — amazing. I learned a lot about integrating technology and how challenging that is to be real with. I thought it was gonna be much easier than it was.

It’s very, very difficult to be honest and truthful in moments where you don’t have anything there. You’re in a green room with thirty people watching you, and you’re battling an insect that doesn’t exist, and it has to come from something, it has to come from somewhere. It can’t just be, “OK, now you’re looking to the left.” You have to see something; you have to really be afraid of what that is. Fear is a very difficult emotion to truthfully [portray]. You can’t wing it.

And you shot that film just when technology had changed drastically. Technology changed while we were shooting that. We redid certain things, because they had gotten new equipment that we could redo. They had this machine that does a facial scan with lasers. You had to shut your eyes, and it was a black-and-white, three-dimensional depiction of you. Four months later, Peter had a new machine that was color, with your eyes open. It was cool.

Any CGI on Predators? Most of it was practical effects. It wasn’t a lot of CGI at all. I was fighting with seven-foot men in Predator outfits and carrying a real semi-automatic machine gun, ammo packs and a real machete built by the guy who built the original machete — things that were real. We shot in Hawaii in a volcanic jungle, and it was incredible; it wasn’t a soundstage. We had some work in the studio, but [for] the jungle stuff, we were in jungle canopy that was endless, with leaves that were two-and-a-half feet, four-feet [in] diameter — just massive. It looked like an alien planet.

Are you anticipating action scripts coming your way once Predators hits theatres? I hope so.

Did that happen after The Pianist? Did you mainly receive offers to play a Holocaust survivor? Oh, yeah, of course. The Pianist basically [was] the world’s introduction to me. I had been working for seventeen years already by the time that film came out. That was my calling card, which is a wonderful thing; but it put a certain image on me. I met an English woman last night who was so surprised I wasn’t English. Three people have told me that. They thought I was from London.

That’s odd. It is. I don’t know why.

So what happened after The Pianist came out? Your life must have changed dramatically. It didn’t come out for almost two years. I had filmed that movie when I was twenty-seven. It went to Cannes, and was very well received in Cannes, and won the Palme d’Or.

Then we had a premiere a year-and-a-half [after] wrapping that movie and the negative broke. I’ve never really talked about this. I was telling my friend about this the other day, and I was like, “I forgot about how horrific that was.” It was a benefit premiere in Century City. Every powerful individual in Hollywood was there, every actor who I admire — Jack Nicholson was there, all these directors. And seven minutes into the film, the sound broke. So they stopped it, and it was a good fifteen-minute wait, and then they tried to get it again, and it broke. So the film wasn’t screened. There was a benefit dinner and I had to go out and put on a good face, ’cause I was the only one who really represented that film.

Because Roman [Polanksi] couldn’t come to the States? Yeah, yeah. I represented that film for six months. I took time off to help them with the movie, and it was heartbreaking. But at the same time, that experience had really given me such perspective on loss that I didn’t really let it break me, even though I felt that this was my opportunity for people to see me. It wasn’t going to happen again. We didn’t have a premiere.

But they ended up seeing it. They did. I never had that before. I never had a film have that kind of acceptance. It did phenomenally well.

You’ve probably been asked about this recently, but it is relevant — Is it intrusive? [Laughs] Then don’t ask.

Were you shocked when you heard Roman had been arrested? Oh, I can’t discuss it. I won’t. It’s a very complicated situation. I don’t want to engage in it. I can’t go there. It’s not fair to ask me about someone that has a place in my life, and it’s a complete separate issue. I don’t feel it’s appropriate for me to comment on it in any respect. It’s inappropriate for me to comment on it.

OK. After winning the Oscar, was it hard to figure out what to do next? I’m sure your representatives gave you a lot of advice. Yeah, I was given advice. You’re always given advice. Every day I’m given advice. You might have advice for me. I don’t know.

No, not yet. OK. [Laughs] I have a rude remark about opinions, but I’ll keep that for myself. But fair enough, people have opinions, and they’re entitled to share their opinion. I share my opinion when I feel that it’s valid. People have different motives for sharing their opinion, which is something you have to learn.

When you’re talking about opinions, are you referring to agents, managers or…? Everybody. Not even in the business, everybody.

Was that a hard time? It was. It was a beautiful thing, but even things that are incredibly beautiful are somehow very difficult to accept.

In what way? My life changed. That means everything is now becoming unfamiliar where I was just getting comfortable. I was in my late twenties. I had a long road as an actor. I didn’t really have big opportunities, but I was a working actor. I had a life; I had a girlfriend. I had things going on that were normal, that felt normal, OK? Normal. But things drastically changed, just on a personal level with my interactions with most people after that.

What do you mean? I mean that people saw me differently. They looked at me in different ways than they would normally. Everybody looks at you in a different way, anyway. But most people were looking at me all of a sudden, whereas I used to get to look at them and observe them. I couldn’t do that any longer. I couldn’t exist in a public place and be relatively anonymous, which, on one hand, I am incredibly grateful for, because it’s the result of something that I worked very hard at, and is a byproduct of the success of that film, and it’s for work that I’m proud of. I’m known for something that I worked incredibly hard at, and made incredible sacrifices for, and then I received recognition for that, which is very rare for an artist; [it] doesn’t usually happen. Look at Scorsese. He’s had a lifetime of brilliant work, and then he’s starting to get noticed for things later in his career. But Raging Bull — if you look at what’s Academy Award-worthy these days, you know, Raging Bull, I believe, could have been a contender. [Laughs] To put it lightly. So I’ve never not felt immense gratitude for that, and I count my blessings every day, all day. But it changed something, and that took a lot of getting used to. It took a lot of acceptance. Because there’s nothing you can do. It is what it is, and there’s a lot of good with it, and there are some negative aspects to it.

How did the media intrusion affect you? Well, it just made me stay home, that’s what it did. I stayed in. Because if I went anywhere, I was photographed and commented about, and I remember someone saying once, “Who does he think he is? He’s out at all these parties, and he thinks he’s a big shot now.” And it was so funny, because I wasn’t at any more [parties] than I ever was before; but now they’re taking my picture. I was probably in a pretty good mood because [Laughs] I was through the arduous process of having to support this movie, and do press, which wasn’t easy. It was a very challenging film to discuss. It was totally misconstrued and negative; there was so much negativity all of a sudden, I was like, “Wow, really? I didn’t think I was anybody.” That’s the thing, and I felt like the perception was everybody was telling me, “Don’t change, don’t change,” but they changed. They watched me differently, and were worried that I was going to somehow change in a negative way because of opportunities.

Do you ever get used to it? To a certain degree, yeah. I’ve accepted it. I still stay in most of the time. Not “stay in” like locked in my house, but my friends drag me out. When you see me go into that club, my friends dragged me out. I had fun, but I know what’s coming. I know what’s coming inside. I know what’s coming outside. Sometimes it’s fun just to go out with friends, and you have to live your life. But I sincerely don’t harp on it anymore. I did, because it was shocking at first.

I remember I bought an electric bass for my girlfriend right around then, and I came out of the music store and there was all this paparazzi. They were shooting me from down the block and in the car, and they had telephoto lenses and they’re like, “Come on, man, don’t be a dick, just take a picture.” And I’m like, “OK.” I said, “You got your picture,” and he goes, “It’s not like we’re gonna follow you.” And I was like, “OK, yeah. You got it, right?” But it was really unnerving.

I got in the car, and three SUVs followed me with walkie-talkies [to communicate] with each other, and my friend headed them off so I could go home without them following me and knowing where I lived. And then, this was a surprise present for my then girlfriend for her birthday, and they published it, and they went back in the store and asked how much it was. And it wasn’t terribly expensive. [Laughs] And they highlighted my underwear and said what brand of underwear, and so all of a sudden it was this kind of scrutiny, and then, like, catching me and telling on me in a way, and they followed me, and so they were aggressive after I gave them the photograph. So there was this new thing, and that is difficult for anybody. You can’t complain about it, because when I see someone complaining about it I go, “You should be very grateful,” and most people feel that way: “Well, you knew this was coming.” But you don’t know that’s coming, and it shouldn’t necessarily come hand in hand with trying to do good work and be supportive of your movies and create awareness of your movies and your work.

It shouldn’t have anything to do with the rest of that. They shouldn’t be circling your underwear and telling stories before [your girlfriend’s] birthday.

But aside from that, I do feel that even with that invasiveness, on the whole, even the paparazzi have been relatively fair to me. They’re nice to me when they see me. A couple of guys will say something to get a rise. But, whatever, it comes with it, and they’re trying to make a buck. I don’t give them a hard time. I’m not fighting with them. I give them a shot if I can give ’em a shot, and I walk away, and a lot of times they leave me be. That took some time, I guess, right?

There are a lot of new young actors coming up in the ranks. What advice, if any, would you give them about dealing with their newfound fame? I don’t know. I don’t know if I like giving advice so much. We’re all individuals, so it’s difficult. The younger you are, the more complicated fame is, for sure, the less fully formed you are as a human being, and the less loss you’ve experienced. Not necessarily; some young people have unfortunately had tremendous loss and disappointments in their life. Even though I’ve had plenty of ups and downs, I didn’t have the maturity and the sense of self-awareness to have gotten me through it as positively as I did if I had been in my early twenties. A five-year difference would have had a big impact. Because you have a tremendous amount of attention: All the girls think you’re beautiful all of a sudden, and people wanna be your friends — and they genuinely wanna be your friend. I don’t feel that it’s insincere. You now emanate some sort of light that you didn’t have before, and it’s created, but it’s too much. Even tons of positive energy on one person is still energy, and that does something. There’re repercussions for that kind of energy. It’s a lot of forces coming right at you, and that’s tumultuous for any young person.

It’s fascinating. It is. It’s an amazing thing. It’s an amazing thing to experience, having been on both sides of the coin.

Is this part of your job, the promotion, the hardest part? No, not really. It’s an awful thing when someone presumes to be rude and tries to take advantage of a situation where they may want something spicy, but they don’t know you, and they say something that’s insulting that I wouldn’t say to someone who was a stranger. That’s not fair.

It’s not everybody. And I grew up going to the Village Voice my whole life; I was around journalists and artists and creative people. Things change the more you become known. It changes the nature of the interviews, and they progressively become more [fascinated] with your private life and less [interested in] maybe what’s important to you or your work.

They’re looking to tear you down. I don’t feel that too much, fortunately. I’m not big enough for them to want to really tear me down. [Laughs] A few people might not care for me, but that’s about it.

Not like Tiger Woods? Yeah, poor guy.

Everything plays out in real time. Just doing research for this interview via Google, here’s Adrien Brody Friday night going into [L.A. club] Trousdale, and here he is at a Lakers’ game on Sunday and last night at a premiere…everywhere you went in the last four days. Oh, wow, right. That is real time. Yeah, that’s weird. And I’ve done more in four days than I’ve done in like four months, ’cause I’m here. That’s strange.

Also, the news coverage is all about celebrity stories and not enough about what’s really going on in the world. Well, what’s your theory on that? Distract people with things that don’t provoke dissent?

Most people don’t want to know. They’d rather tune out. We’re raised with a certain level of apathy. I was just in Paris, and I was talking with a guy [I used to know] about our past. He used to be a punk rocker, or just a punk — not a rocker, just the lifestyle — and I played a punk rocker in Summer of Sam. I grew up in New York. I went to the School of Performing Arts. I knew lots of individuals, people who weren’t afraid to show their individuality, and a lot of hoodie kids.

But that’s part of growing up in New York, and I’ve changed a lot from that; that doesn’t represent me any more, I’ve matured a little bit. And this guy, you’d never see it in him, right? He has this beautiful apartment in Paris, he’s very knowledgeable about art, he’s well read, and we were discussing how we change, and how all these things affect our lives. He was saying that part of their studies in school was [focusing] on society, and your place in society and it’s not quite as individualistic. Basically he was saying that the way they were taught in public school in France instilled a whole belief system that isn’t instilled at all here. Hence the reason they’re always on strike, something’s always pissing them off. [Laughs] They’re standing up for every kind of thing that they believe in; they stand up for change, whereas there’s less of that here, or very little.

Except for the Tea Partiers. Do you like Paris? I love Paris. I do. Love it. I could live there.

Were you there to promote a film? Manolete just came out in Paris — that’s why I was in Paris. I was there supporting the movie. It’s gonna come out in Spain and the [United Kingdom]. It doesn’t have U.S. distribution yet, unfortunately.

The film about the famous Spanish bullfighter of the same name, which you made with Penelope Cruz… Did the uproar from animal-rights activists hurt the film? They had some concerns. It doesn’t glorify bullfighting in the least. It’s about a guy who lives a tragic life and dies in the ring. But I understand their concerns. I’m an animal lover myself. I made the production sign paperwork that no animals would be harmed at all in making the film, and they weren’t. It hasn’t been an issue. If it’s an issue, it’s misplaced.

You mentioned “hoodie kids.” Were you a hoodie kid growing up? Well, I’m somewhat. I wasn’t a hoodlum, no; but there’s a style and an energy that some young, adolescent boys get into. The difference [with] some of my friends was that I came from a complete loving family unit that supported my creativity and individuality. They may not have understood everything that I was experiencing or dealing with as a teenager, but there was much more support in my home than any of my friends had. My friends that failed to get past that adolescent aggression, that’s unfortunately a part of [life for] many young boys — and now girls, even — in an urban environment.

It’s a product of, again, cultural influences that are prevalent in an urban environment. There comes a point where you associate with people that identify with it, and New York was a little different when I was young. New York City was different, the boroughs were a little different. Certain areas have become gentrified, some things for the better, some things for the worse; but it’s shuffled whole neighborhoods around. That’s part of just growing up in New York.

So I never really try to emphasize that. I’ve always had a conscience. I’ve never been able to suppress my conscience and my empathy to a certain degree, so that limits your hoodie-ness.

Was there a moment on a particular film where you realized you could do this, and do it well? I was always an actor — not in a way that people might presume actors to be, ’cause I believe there’s a presumption that they like attention all the time, and that they’re very outgoing. Acting is perhaps misunderstood. I’m a relatively shy person. I often liken it to my mother’s approach as an artist, because she’s a photographer and she sees so much in a situation that very few people might see. She’ll see so much happening beneath the surface with an imagery that says something else. And I have a fascination with a similar kind of thing where I see details in people’s mannerisms, or beneath something that’s said to someone else. All these things that lay beneath the surface and things that are really special and that make us all so unique.

Growing up in New York, I encountered so many different kinds of people everywhere. I went to the School of Performing Arts, but I feel like my real acting training came from going to and from school on four different trains each way, because of how many human beings I’ve encountered, between homeless people and immigrant workers and shark businessmen and every kind of human being — every kind of human being every other step. My natural fascination was that I gravitated toward their mannerisms — not to use as an actor, just because I’m curious, I guess. And rather than capture the image with photography, I feel like I capture it somehow and remember details very specifically, and I retain things very easily and evoke them later.

So would you say you’re an observer of human behavior? To a certain extent. An observer, yes, but it’s not just about observing human behavior. It’s about making it exist again somehow, not just watching it, ’cause if I put it in those terms, I don’t feel like that’s really what happens. It’s that I absorb human behavior, rather than observe, and then it stays there somehow.

Why do you think people have a misconception about actors? People often make assumptions in general. An actor has a responsibility [to be] connected and present and able to be very malleable and exist in a space that isn’t his or her own on set, and when they’re working. I’m not able to fully engage with you when I’m working on a set. I couldn’t do an interview justice because it’s impossible for me to separate from myself, and then to engage as myself, and then go back to [that character]. So then my producer who needs that interview might say, “Oh, he’s being pretentious.” But it’s detrimental to my process of being truthful [to the character], nothing more. Sometimes I am very gregarious and outgoing, and sometimes I’m not. I’m relatively introverted, and I’ll stay by myself; but they’ll misinterpret what that is.

There are moments where you do all the preparation you can do, and then you have your opportunity, and it’s usually a limited, limited opportunity; there are a lot of obstacles. They’re losing the light, they’ve shot everything else, somebody’s not in a good mood, there’re people in your eyeline. There are all these things, and you have to, against all that, be emotionally, completely open and completely vulnerable. And there are moments when you’re able to truly do it, and truly let go and do it with all those obstacles. Those are very powerful personal triumphs because they are so, so daunting, and they are so, so challenging, and it has to look easy. It can’t look like you’re struggling unless your character should be struggling. [Laughs] It can’t be an ounce of effort for a minute; it has to just be natural and connected.

There are so many variables that go into a film becoming a success. Magic almost has to happen on set, the studio has to support the end product with marketing and distribution. To be good, not even just a success. [Laughs] It might be successful, but not good.

That’s true. I don’t look at my movies. Yes, they have to perform and not lose money for the studios or the investors…but I don’t look at success on just the numbers; it has to be good. And for a movie to be great, I agree with you: magic has to happen in so many pieces, and so many complicated puzzles have to entwine, because otherwise that element is missing. And it has to be consistently done throughout the film. A great movie doesn’t have five great scenes. It has to have eighty percent amazing, enthralling moments, and then you can tolerate a few things that don’t necessarily work because they don’t even register because you’re so caught up with the rest. If you have five great moments and you’re not connected to the film, that’s not magic.

And it happens… Often?

But in the end, it seems like the responsibility for a film’s success falls on the lead actor and the director. They seem to get the blame if it doesn’t perform. How much input should an actor have on a film where he plays the title character? Depends. If you have the good fortune of working with someone who is incredibly experienced, and is conscientious and thoughtful about a number of matters beyond what makes him or her look good — ’cause a lot of the notes you’ll get from an actor are for their benefit. Rightfully so, because you want to protect yourself as an actor, and you aren’t always protected, and you know what helps you, and what works, and so you are entitled to voice that. It may fall on deaf ears, but that’s one of the advantages of having a reputation for doing good work and working with gifted directors. I’ve had a lot of experience with a lot of very experienced craftsmen, and I’m very observant — including with Roman, who I spent six months, six days a week, without a stand-in, doing every scene. Six weeks of that movie, there wasn’t even another actor on the boards. I had a viewfinder. I learned more than I could ever learn in any film school from just that time period.

If you work with people that you know — [with] a lot of things, it’s not really my place to say, but if there is something that I have an idea [about], a creative idea, oftentimes if it’s good, directors will take that idea, and there’re no issues with that. It is such a collaborative process that the beauty of it is working with people that embrace your investment in it, and you embrace theirs, and then you have an opportunity to do something really special together. Being the director doesn’t mean you have to make every decision yourself; you have a team of creative people involved to help you make the best decision. Sometimes something on the page works but doesn’t feel sincere when you’re doing it, for whatever reason. Or some of the dialogue doesn’t really feel right, or the other actor is doing something different, and the director is trying to get them to do something, and they don’t necessarily change. So you have to respond to that differently. Ninety percent of the time I’ve worked with really great collaborative people, amazing and open. A couple don’t [want to collaborate]. A couple want to be the boss, and that’s fine with me, too. But it’s different for the process.

What do you think of a moviegoing public that will go to see a film because it’s number one at the box office, and not necessarily because it’s good? “What should I read?” and there’s a bestseller list. So you say, “Oh, these are doing very well. I should read this book.” But there’re another thousand books that are really interesting. [People assume] bestsellers are typically better. Well, not necessarily. Some movies do very well because people love the movie and there’s a lot of word of mouth, and then you can have a movie that lasts. But if you’re looking at a movie just because of its opening weekend, and you’re only gonna go to see a movie because of that, then I don’t know. I don’t know what motivates people. Some movies that I have no interest in are very popular. I would have no interest in doing them, even if they are popular; they don’t speak to me. So I try to do movies that I would want to go see. That’s part of the prerequisite.

What kind of movies are those? It varies. But, for instance, Wes Anderson’s movies. If you have an opportunity to do something like that, and it’s a comedy, but it’s thoughtful and it’s unique… I did one — The Darjeeling Limited.

Right. You also were a part of Fantastic Mr. Fox. Oh. Well, that’s not the same. It’s great, but it’s not the same.

You’ve otherwise done very little comedy. Because people don’t think I’m funny.

You’re joking, right? What people? I don’t know. Who’s hiring?

That’s all it is? Yup, it is. The opportunities that have come haven’t been things that have spoken to me. But I have a really cool drug comedy that’s coming out called High School. It’s great. I play Psycho Ed, who is this weed-grower extraordinaire.

Oh, even more interesting. He’s a mastermind, horticultural expert. He was an attorney who kind of went off the dark side and became this maniacal weed wizard. It was really fun. It was a blast.

Should I ask what you did to research your part? It was a lifetime of work. [Laughs] No, actually, I did that role completely sober. I may have had a glass of wine or something one of those nights, but I was just focused. I didn’t feel it was necessary to blaze to look that way or to feel that way. Whereas, if I was younger, it might have been the perfect excuse.

You were interested in playing two iconic figures: Spock in Star Trek and the Joker in The Dark Knight. What happened? There was interest in me to play Spock. I thought it would be interesting. I really wanted to play the Joker. But Heath [Ledger] did an amazing job in that. Yes, it would have been a great role — it is a great role, it’s an iconic character. There are very few tremendous, iconic, rewarding characters in big studio movies. They go to a select few individuals. But it was done perfectly. It was beautiful, and you can’t look at what you didn’t get. You let it go. I would have loved to have done that movie, yeah. Chris [Nolan] is an amazing fucking director, and I tried to work with him. I met him previously on something, as well. So I thought, “Oh, maybe there’s a good chance.”

According to studio spin, the star system has turned out not to be as vital with films like The Hangover and Avatar. What does that mean for you as an actor? [The Hangover] was incredibly funny, and a wild success based on a lot of word of mouth as well. Everybody said, “Have you seen this movie? It’s hilarious.” That tapped into something that people wanted to see. Just because you put a name actor in a movie doesn’t make it a great movie or a successful film.

So you don’t think that the studios are thinking, “Well, we don’t need to pay A-list actors $20 million anymore. We just need a wow factor”? No, that’s not true. I don’t think so. There’s always going to be a place for Tom Hanks and Tom Cruise and Brad [Pitt] and George [Clooney]. Those guys bring in box office, and they try to select their movies wisely. But they also have the best of the best involved in making a great film. You have all these elements working in your favor. Plus, people are fans, so they want to see you work, and so there is a built-in audience. If you’re talking on that level, that’ll always work. If it’s being said, it’s an excuse to reduce salaries. Everything’s been spun. Movies are very profitable, yet actors’ salaries have been reduced because there is a certain desperation, and people aren’t working, and they’re not making as many movies. Therefore there are more people unemployed, and so your competitor will do the movie for less. So then they say, “Well, you should do this movie for less, because somebody else is going to.” And that’s how it goes. Meanwhile, the movies continue to be profitable.

How do you deal with that? I don’t make my decisions based on the salary.

You’re racing in this weekend’s Long Beach Grand Prix. What do you get out of racing that you don’t get from acting? Well, it’s a childhood fascination that I’ve had with cars and speed, and I love cars. I used to buy old muscle cars and fix them up and sell them so I could buy another one and get to know them.

But it’s very dangerous. I agree, I agree. I ride a motorcycle, too, which I feel is probably very foolish, and at the same time try to limit the riding that I do these days because the odds are good, in L.A. especially, in traffic [that an accident could happen]. But I love to ride, and I love how liberating it feels. I don’t know. Some would say I’ve matured a little bit; I’m not entirely grown up yet.

But wait. Tomorrow’s your birthday, right? Yes, but it doesn’t mean I can’t drive fast.

No, obviously. But birthdays can make you introspective. We tend to look back at what we’ve accomplished, and think about what we still want to accomplish. I’ve become incredibly grateful, even more so than my standard level of gratitude. I’ve become more cognizant of how amazing it is that I’ve made it this far. I have it on my phone [Laughs]: “You made it!”

Well, what does that mean? You didn’t think you’d make it this far? It’s been an amazing life. I don’t know. I don’t know the answer. I’m not pessimistic in that sense. I’m surprised, but I don’t take for granted that I could have easily not been here. It’s something that we all should feel.

If you’re racing cars, I can understand your thinking that way. Yeah, well, OK. That’s part of it.

There’s not anything in particular that you still want to accomplish? Sure, there’re many things that I want to accomplish, but I don’t think about that on my birthday. There’s a lot further to grow and do, but I try to embrace the now, especially on my birthday. I’d like to be able to grow and be more positive and to remain enthusiastic and creative in whatever I choose to do, whether it’s acting or other things in my life; to continue to maintain the enthusiasm that I have managed to maintain about so many things beyond acting.

What, if anything, would you change about your life if you could? That’s a good question. [Long pause] What I would change if I could… I wish that my grandparents were still around, or at least would have been around to see a change, because I was struggling a lot, you know. My grandfather was a wonderful influence, but he aspired to be an actor to a certain degree. He died when I was seven. He would’ve loved to have watched [me become an actor]. They made incredible sacrifices to come to America, and have a life here, and give my mother a life here, and to see a dream like mine come true is very rare. It would have been a big gift if I’d been able to share that with them.

I feel like whatever I change, it’s out of my hands, so I don’t think about it. I have really good people that work with me that I like, and I have some great friends. I’m working consistently on things that inspire me, and I’ve found some sense of balance. I work when I want to work. I don’t feel the pressure that I used to feel as an actor that I may not have an opportunity to work, that I will not find gainful employment with something that inspires me, that I might have to take work just for the sake of working. I feel honestly so fortunate to have that, that I don’t think of things that I have to change. I don’t consider it.

When a problem comes up, I try to resolve it thoughtfully, and problems do come up. But that’s nothing to discuss in an interview, necessarily, my own personal things that I’ve had to deal with. But life is blessed. Life is blessed, for sure. [Laughs] And I mean that sincerely. I am incredibly grateful.