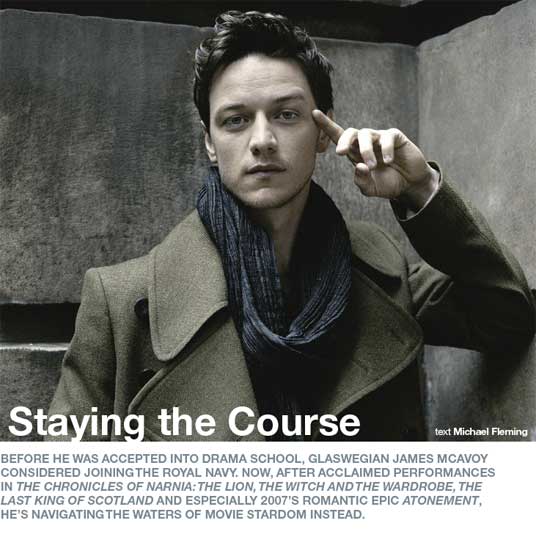

tonement has the feel of a classic David Lean film. Was director Joe Wright consciously trying to achieve that? I suppose so. We all watched Brief Encounter, which is one of my favorite films, and getting to watch that on a big movie screen with a couple of cast members was a privilege. I watched it a few times. We weren’t trying to behave like people of the times. We were trying to act like the actors of that time, and apply that acting style. Not 100 percent, but fifty to sixty percent of the acting style harkened to a style that has died out. That was good fun.

tonement has the feel of a classic David Lean film. Was director Joe Wright consciously trying to achieve that? I suppose so. We all watched Brief Encounter, which is one of my favorite films, and getting to watch that on a big movie screen with a couple of cast members was a privilege. I watched it a few times. We weren’t trying to behave like people of the times. We were trying to act like the actors of that time, and apply that acting style. Not 100 percent, but fifty to sixty percent of the acting style harkened to a style that has died out. That was good fun.

This is probably the classiest film to ever have the word “cunt” displayed so prominently on the screen. When you read the Ian McEwan novel it’s based on, or the script, did you consider how Joe Wright would shoot that scene? No, I don’t think I did. It was the lowest on my list of priorities. I knew it was coming, because I’d read the book. I thought it was a beautiful use of the word, and I could see how it was meant to be. One of the great things about the film is, it doesn’t let you settle. You can watch a lot of films, and within the first five or ten minutes — maybe less, sometimes — you’ve evaluated the visual language and you know the style of performance and you know exactly what you’re going to get. You might not even be aware that you’re doing it. Here, you think you’re in a British costume drama with a stiff upper lip, and then that world gets smashed into your face, and you’re glad you’re not watching the usual British costume drama. It’s a very modern-feeling film, actually, set in 1935, using modern techniques to tell the story. I wasn’t wondering how he was going use it, I just was glad he was using it.

Why do you seem to be the go-to guy for period pics? I don’t know. I find it weird. Though I don’t really consider this a period film. It is set in a period, but it feels like a very modern film. You said this was something David Lean could have made, but in a way, I don’t think David Lean would have rewound scenes, and shown you the same scene three times, from different points of view. Or jumped into the future, and had an actor speaking directly into the camera and talking directly to the audience. Even though it is set in a period, I found it more like a film of now. Also, unless it’s sixty to eighty years ago, I never consider it a period film. I grew up in the ’80s, and I was born in the ’70s, and I find it weird when people call those period films. But I know what you mean.

How do your challenges change as you go from auditioning for roles to a young star cracking through, trying to select the right things? It’s trying to find something you can do well that’s difficult. When you audition for something, you physically get to prove to yourself that you can or cannot do it. At the end of the audition, you have an idea whether you should get that part or not. You might not always get it, but you know if you should do it. If it’s a fantastic part, and you’re really excited about playing it, does that necessarily mean you can? That’s the biggest challenge.

You grew up working-class, and you worked a lot to get to this point. How much do you have to resist the urge to take everything? Are people telling you to be selective? I have recently done a lot. AfterAtonement, it took four months before I did Wanted, and [since] Wanted, I haven’t done anything. I probably won’t do anything until quite a bit into this year. I’m conscious of having done a lot and never really stopped, so I feel it’s important at this time to take a little bit of time out, and reinvest in life a bit instead of just working. You can’t live your work, and that’s nothing to do with strategizing. You’ve got to enjoy your life, too, and when you start to overwork, that’s a bad thing. But there is a part of you that says, “This is not in my ethic. This is not right, to not take work when it is offered.” So it’s very difficult, and it feels very strange. But it has been beneficial.

As you handle that downtime, what do you like to do? I hike a lot, spend a lot of time outdoors, play football [and] cook a lot. Those are the things I like most.

You’re an avid Glasgow Celtic football club supporter. Let’s say you’re driving along and you see a fan of your rivals, the Glasgow Rangers, broken down by the side of the road. What do you do? I definitely stop and help him, although I would be given shit from a lot of my friends for doing so. I’m more hands across the divide, and the whole Protestant-Catholic thing doesn’t make much of a difference to me. If we’re playing them, I’m going to let them have it, but I want them to do well. It increases the profile of the Scottish game.

Growing up in Glasgow, what was your fondest recollection of going to the cinema? My grandmother taking me to see The Goonies with a couple of friends.

Why The Goonies? The reason I loved it so was — even though I had never been chased by mobsters after pirate treasure — in my mind, all the adventures me and my friends had were just as big. I felt the film captured exactly what it is to be that age, to have friends and love your friends so much that the adventures are magnified and made much bigger in your mind than they actually are. That makes it wonderful.

You initially wanted to be a missionary, and then joined the navy… No, I didn’t join the navy. I considered the priesthood for a couple of weeks, and it was one of those things in one of the first interviews I did, about eight years ago, [that] has been blown up and made bigger. Most of my mates thought about it at the same time. The navy was something I considered seriously, but I got into drama school and did that instead.

What was it about acting that pulled you off your plotted course? I was given a part in a film when I was sixteen — out of the blue. Then, after two years of not doing any acting, I was deciding what to do with my life. I’d been accepted to university, but I wasn’t sure. I could have gone into the navy with the qualifications I already had and maybe done all right in that. I thought, “I’ll audition for drama school, and then, if I get in, I’ll have three options of what to do.” So I got into drama school, thankfully.

And now they’re calling you the sexiest man in Britain. How close is that to how you see yourself? If I’m being honest, very far away from the way I view myself. It’s nice people are saying nice things. I’m glad they’re not saying I’m an ugly mother. But I don’t get out of bed feeling any better about myself because of this. It’s very nice and flattering, but strange.

Would you have been more affected if you were a teenager and all this was happening to you, instead of at twenty-eight? Probably, yeah. I’ve always tried to have a level head. But if it happened in my teens, or even my early twenties, it might have gone to my head. Even more than the press reaction, I wouldn’t have had as much time to learn how to do my job, or play the types of characters I’ve gotten to play before anyone noticed. That, more than anything, has changed me hugely.

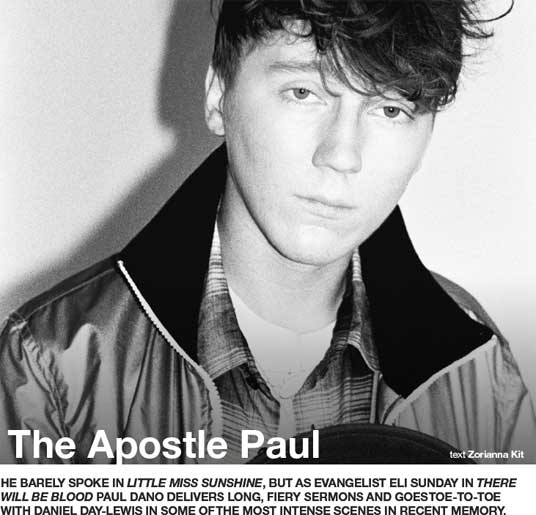

our performance in There Will Be Blood is outstanding. But you weren’t originally cast to play Eli Sunday; Kel O’Neill was. What happened? I had been cast in a smaller part in the film, the part of Paul Sunday, the brother at the beginning of the film. It was one scene. And I had a relationship with Daniel from a previous film we’d done [The Ballad of Jack and Rose]. The whole experience was a blur because I got down to Texas not knowing why I was going there early, and there ended up being this change of plans. I ended up doing this Eli part. I only had about three-and-a-half days to prepare for my first day of filming, so it was sort of a whirlwind of an experience, and I had to throw myself into it as fast and as best as I could. I didn’t have time to look back or second-guess myself. I just sort of had to run with any animal instincts I had.

our performance in There Will Be Blood is outstanding. But you weren’t originally cast to play Eli Sunday; Kel O’Neill was. What happened? I had been cast in a smaller part in the film, the part of Paul Sunday, the brother at the beginning of the film. It was one scene. And I had a relationship with Daniel from a previous film we’d done [The Ballad of Jack and Rose]. The whole experience was a blur because I got down to Texas not knowing why I was going there early, and there ended up being this change of plans. I ended up doing this Eli part. I only had about three-and-a-half days to prepare for my first day of filming, so it was sort of a whirlwind of an experience, and I had to throw myself into it as fast and as best as I could. I didn’t have time to look back or second-guess myself. I just sort of had to run with any animal instincts I had.

When you found out your part was going to change and become much larger, what was going on in your head? I allowed myself a couple of minutes to go, “Holy shit.” But it was pretty much right down to business, which I would have done anyways in order to avoid getting too crazed about it. But I was definitely — especially when you get to engage with someone like Daniel Day-Lewis, who is so immersed in what he does — having that time issue, so I probably was like, “Fuck!”

How did you prepare for a role in only three days? Luckily, I had already done some research for the period, just for the other part I was going to play. So I was comfortable with the lifestyle and the time period. I did try to muster up some things about evangelical preachers from just reading the Bible and stuff. I have to say the most valuable thing was we had these wonderful sets from [production designer] Jack Fisk. The most valuable thing was just getting in the clothes and spending time in the church — they had a ranch. It was really fascinating how quickly I felt right at home. Maybe it was because everything felt so authentic, you know?

So Paul Sunday wasn’t originally going to be the twin brother of Eli Sunday? No, originally he was not a twin. Then, once I was down there, since we were already filming, we just said, “OK, maybe we’ll take a little Cain and Abel idea, or East of Eden idea, and make ’em twins.”

You mentioned that you worked with Daniel Day-Lewis on The Ballad of Jack and Rose. Did he recommend you for this movie, or was your casting coincidental? What happened was, Paul [Thomas] Anderson saw The Ballad of Jack and Rose, and that was about the time he was starting to talk with Daniel about this film. He really liked my character in that. He asked [Ballad of Jack and Rose writer-director] Rebecca Miller and Daniel about me. I don’t know what they said. Hopefully they said good things. I’m pretty sure they did. I ended up hanging out with Paul here in New York, just based on him seeing that film. But we weren’t talking about this film at all. We just met one day and hung. He liked the film and my character. Then eventually, down the line, I guess from that, he sort of had me in mind to do a part in his film.

You have some pretty gnarly scenes with Day-Lewis. Would you have been more intimidated working with him in this capacity had you not worked with him previously? I can’t hypothetically say, but I will say that it definitely made the experience better already having a relationship with him. It certainly helped, first of all, knowing that he’s a very kind and cool and gracious man in real life, as a person, because the way we engage in this film we certainly don’t get along. The second time around working with him was much more fun because maybe I was a little more confident in myself, but I was sort of looking forward to the experience of getting to engage with him on that level. We certainly weren’t buddy-buddy on set. We didn’t say probably more than a few words to each other [the entire] shoot. But that was something that was attractive and appealing and fun to engage in rather than be worried about or turned off by.

How much of your sermons were improvised and how much were scripted? Paul is just as good a writer as he is a director. I always thought of him as a director first, maybe because I’d never read one of his scripts. But, God, the language and the words were soooo good that he wrote. It was all there. We did small improvisations every now and then, and Daniel certainly improvised a few things, but no, I never really felt the need to do that. The sermons? We worked on them a bit. They did change, and Paul, every now and then, he’d re-write some stuff. We definitely worked on it, but going into the actual takes, by that time I felt it was there. And my job was to live up to that, and then hopefully add and contribute to it.

Having researched evangelical figures, do you think they are true believers, or just really good actors?Mmmm, I’m not going to say what I think of them on a personal level. But for Eli, I was looking at it through his eyes, trying to discover his eyes. So I definitely think Eli’s a bit of an actor.

You were also in Fast Food Nation. Have you sworn off fast food? Yeah, I can say I can’t eat fast food after reading that book. Not because of the movie, but I read the book for the film, and there’s some pretty astonishing stuff in that book. [Writer-director Richard] Linklater is a guy whose films I like. He’s a very cool dude, very fun to work with, and I had a good time doing it. I was just on the film for a week or so.

You unsuccessfully applied to get a job at McDonalds. Why didn’t that pan out? Yeah, my two local McDonalds near my apartment here in New York. I applied. I don’t know what happened. I remember knowing I wasn’t going to get the job [at one of the locations] because they looked at me like I was crazy asking for a job there. I don’t know why. I don’t dress nice or anything. I look like a schmuck. I don’t know if they knew I was an actor or…

You’ve also got a band called Mook. [Hesitates] Yeah. I don’t really like to talk about it. I don’t know.

Music is a big part of you as an artist, whether it’s acting or being in a band. It is. Music has been a big part of my life, whether it’s playing an instrument or as a listener. It actually has a tremendous influence on acting. I don’t know. I get weird talking about that.

Do you feel like a cliché — an actor who’s also in a rock band? Perhaps. I also feel like it’s weird, too, you know? I hope I don’t take myself too seriously, but I take those things that I’m passionate about seriously. My ambition right now is completely with acting. I really enjoy it, and I really enjoy getting to work with people I can be friends with, or who I look up to. I’d like to continue to do that. I really care. It sounds corny, but films are sort of underappreciated in a really weird way. Film as an art form is underappreciated. There’s a small community of the movies I go to see compared to something that usually ends up making a lot of money, that most people see.

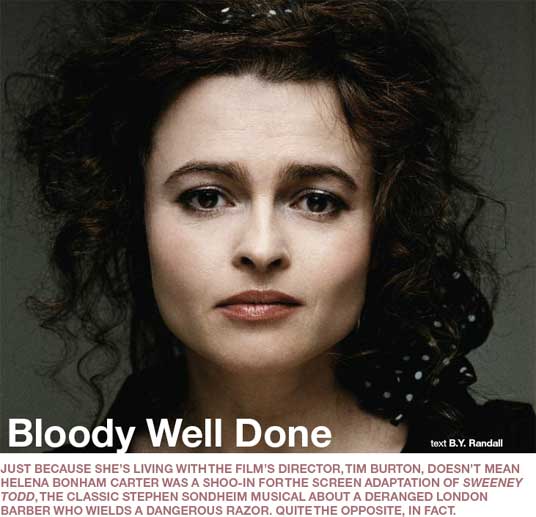

ou’re sort of the black heart of Sweeney Todd — if it has heart. It’s a questionable one. What I love about [my character] Lovett is that she thinks she has a great big thumping maternal heart, and yet she’s just so delusional.

ou’re sort of the black heart of Sweeney Todd — if it has heart. It’s a questionable one. What I love about [my character] Lovett is that she thinks she has a great big thumping maternal heart, and yet she’s just so delusional.

Looking over your filmography, one sees absolutely nothing that would’ve prepped you for the role of Mrs. Lovett. Was singing one of your hidden talents just waiting to be brought out?Well, it was so hidden [even] I didn’t know about it. It was a dream that I thought would just remain a dream, because I came out of the womb wanting to be in a musical, but I just thought, “Well, that’s just not going to happen.” But then when Tim said he was going to do a musical, and it was Stephen Sondheim, and it was Sweeney Todd, I just thought, “I can’t not try and see if I can sing.”

He said I’d have to audition along with everyone else, and I went to this singing teacher, who sadly died the week we finished shooting, named Ian Adam, who I met over the years. [He said,] “No, dear, you’ve got a voice, come to me.” He tended to tell everyone they had a voice, but he was a magician whose specialty was getting nonsinging actors to sing. I told him, “Look, I just need to learn to sing. Will you teach me Mrs. Lovett in two months?” He said, “Of course I will, darling, but why you want to play that hag, I have no idea.”

Did you ever see Angela Lansbury in the role onstage? I didn’t ever see her, but I heard her. She did it in America when I was thirteen, in 1979, and I heard it literally within a month of it coming out. One of my mom’s best friends sent it from New York, knowing that my parents would love it because they were big Stephen Sondheim fans. I just remember scouring the lyrics, because it came in a huge long-playing record with all the lyrics, and I just immediately starting singing along to it. I just loved every bit of it. The first ballad was just so galvanizing, so invigorating and thrilling. I loved all the men’s tunes, and had them around in my head for years.

Actually, with [my son] Billy, when he was a baby, I’d sing “Nothing is Going to Harm You” as a lullaby. I’m a big show-tune person. I always have been. But Sondheim has always been like the god of gods.

Describe your audition for Sondheim. It was taped, so Sondheim wasn’t there in the room, I will give you that. In fact, he wasn’t in the room for anyone’s audition. Tim felt that would just paralyze. So what I did was audition for Tim, which was strange enough, up at a local recording studio. I did about five songs, only because I wanted to and I worked so bloody hard on it for three months so I just thought, “No one is going to stop me now.”

I also thought this was going to possibly be my last chance at a recording studio, so I just went for it. Although Tim did say, “You can really stop now. Less is more here.” Then I didn’t hear anything for five weeks; he wouldn’t talk about it, and he went off and auditioned other ladies. So I didn’t technically have the pain of auditioning for [Sondheim], except for the video, which still had the stakes. Once I got it, then he came to London, and I had to sing a whole lot for him. That was embarrassing…scary. He gave me some notes. He was very easy, actually. It’s safe to say I was overcomplicating things because I had an idea that she should be a prostitute as well as everything else, and he thought it was a very bad idea. I did come up with an idea every five minutes with Tim, which drove him bonkers.

Was there any studio interference? The studio was probably a bit suspect because it was like the obvious choice, and yet it wasn’t, in a way. It wasn’t the easy choice, put it that way. On the face of it, it might’ve looked like Tim rolled over one morning and said, “I wonder who could play Mrs. Lovett? Oh, you’ll do! Do you want to play it?” “Yeah, yeah, that’d be lovely!” It wasn’t like that at all. I didn’t want to be chosen because of my relationship with him. I find that utterly patronizing. I didn’t want to justify every single day why I’d been cast. The studio initially may have thought, “We don’t want the Tim Burton Repertoire Company,” but the fact Sondheim was so certain really helped me.

Emma Thompson, Toni Collette, Annette Bening, even Cyndi Lauper were being considered for the part. How much resistance did you encounter? I just had Tim’s realism. He said, “Look, if you cannot sing this, you might not be right for it. I’m just going to be as objective as I can.” He did torture himself, and I could see it; it was like the elephant in the room. He didn’t tell me, but he had a hunch that I was physically right for it. He’d always seen that me and Johnny [Depp] would make what he called in a makeup test “a lovely couple.” So physically, I was right, but he was never going to cast me unless he was convinced I could sing it. Living with it was quite painful, because I had to know if I got it or not, and he was ruthlessly impartial. I had no idea for five weeks; I had absolutely no idea what was happening. He very politely summoned me at some point and said that he did want me, finally, but even then he said, “Not because you’ve got the best singing voice, but just because you’re right for it.”

This is the fifth film you’ve done with Tim. Does he consider you his muse, or is this like the mixed-doubles version of Scorsese-De Niro? No, I don’t think he’d call me his muse at all. It’s a given that I won’t be in some things. Actually, it’s Dick Zanuck, who’s his producer, [who] suggests I should be in something. So I wouldn’t consider me his muse, although he does take 7,000 photographs of me. I spend most of my life holding a pose. I’m always flattered, because I admire the man so much, and I admire his creative imagination, and I felt like that before we were involved. I feel very, very privileged that he should want me to be in his imagination, as it were.

This is your third film working with Johnny Depp, who stars in the title role. Do you share a kindred spirit with him because you both choose atypical roles? There’s a similarity between us, even though I sort of feel I maybe flatter myself; I’d say we have an instinct, or compulsion, to cover ourselves up. In fact, on this, I wanted teeth, and Johnny wanted to have a fake nose, and we had to restrain from completely disguising ourselves. We’re both character actors, really, that don’t necessarily look like it. What is the other similarity? Oh, we hate watching ourselves. We definitely have a similar sort of look. We’re both blind, and have the same frown line. We both squint terribly.

It took twenty-eight years for Sweeney Todd to make it to the big screen. What took so long? I don’t know. It wasn’t the hugest commercial success to begin with, and Sondheim has always said it was a flop technically when it came out. Although since Tim has been making it in the last year, the amount of kids that have come up to us — teenagers who have all done it at school — we found out it was the most performed high-school musical in England.

Really? They don’t find it objectionable? Not at all. They love it, and they love the gore. It’s a melodrama, so the gore shouldn’t be taken too tremendously seriously. What I find remarkable is that it’s so bloody complicated, so how can the kids do it?

Tim’s explanation for the amount of gore in the film has been that the film is about rage, and he really wanted to rub people’s faces in it to get the full benefit. True? Yeah, definitely the rage is acted out. [Laughs] On top of that, he says Sweeney’s the character he most identifies with, so you can see what I live with.

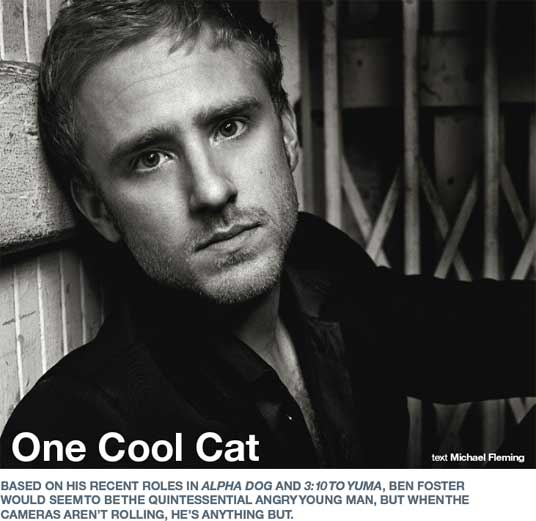

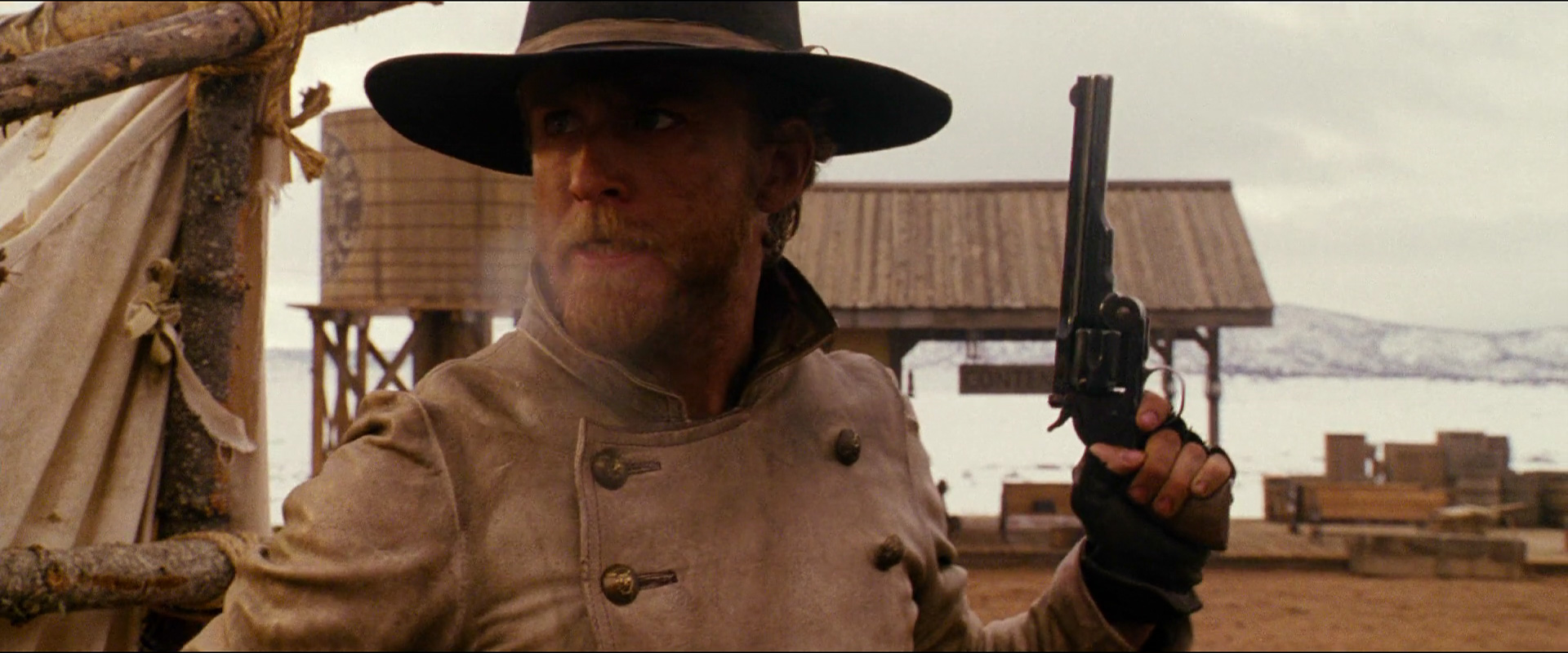

he model for Daniel Day-Lewis’ villain in Gangs of New York came out of a history book. The model for Javier Bardem’s outlaw in No Country for Old Men came out of a book, too. Was your character Charlie Prince in 3:10 to Yuma based on a real historical bad guy? Not a particular outlaw. There are so many Western outlaws that my fear was, I didn’t want to repeat or imitate a life consciously. There’s a collective stealing that we all do, but I was looking more at mountain cats and David Bowie.

he model for Daniel Day-Lewis’ villain in Gangs of New York came out of a history book. The model for Javier Bardem’s outlaw in No Country for Old Men came out of a book, too. Was your character Charlie Prince in 3:10 to Yuma based on a real historical bad guy? Not a particular outlaw. There are so many Western outlaws that my fear was, I didn’t want to repeat or imitate a life consciously. There’s a collective stealing that we all do, but I was looking more at mountain cats and David Bowie.

Come again? I watched documentaries for how they moved. The mountain cats were indigenous to the territory we were working in. It’s basic. One learns from environment. If one is a hunter, how does one hunt?

There’s sort of a feline quality. And that lent itself to glam-rock, which was something [director] Jim [Mangold] and Arianne Phillips, our wardrobe designer, fixed on. These outlaws were rock stars. When you don’t have money and then you come into money, you dress in a certain way. There’s a rebellion and a freedom and sexuality in that — an electric sexuality, which was something we wanted to explore.

So a little Ziggy Stardust in the Old West? It was not an imitation as much as a tonality, which just felt right. It doesn’t necessarily make sense, but you go down so many roads, and wait until it just feels right. And you just do that.

How did you get a sense of what being in the Old West was like? Researching the time; what was the territory like, what was the weather like? How did these men live? I was reading up on outlaws and the simplicity of their lives, which was, you live on your horse and you’ve got your guns, and that’s how you survive. So the ethics of survival don’t necessarily apply to our lives. But what really informed it was shooting on locations. Working with these guns, which are not the most efficient machines. They have a lot of character, but they have a particular weight, and a particular smell. And when you’re out in the desert, the sun has an effect on your skin, and on your eyes. Just being in the environment informs the performance.

You’ve said you look for what each character you portray loves as a motivation to play that character. Describe Charlie Prince’s love for his outlaw boss? To make sense of Charlie’s actions, it had to be an act of being in love. And that makes us all insane; love has that quality that allows us to transcend our normal morals and ethics. So what that relationship was, I don’t think was necessarily on the page or, in a sense, necessarily sexual. But Jim and I talked a lot around it; we were interested in a sexuality, and a propensity for violence, that perhaps was somewhat ambiguous.

Did Russell [Crowe] play a role in figuring out that relationship? We talked about other things, but we didn’t talk about that directly. We’ve all been in love, and felt love for people who didn’t necessarily love us back. So that didn’t feel like something we needed to verbalize. There is a tendency to over-articulate. When you get excited about a project, you want to get right into it, but if you discover everything before you shoot, you’re kind of dead in the water. So you just kind of keep it warm and feel it out, rather than think it out.

Tom Cruise fell out of playing the outlaw Charlie Prince, and Columbia followed suit, and Mangold had to scramble and pare back the picture to keep it together. How did you convince Mangold you were the outlaw he was looking for? Alpha Dog must have been a powerful calling card. He hadn’t seen that; he’d seen my work in Six Feet Under. He didn’t say what that showed him. It was an audition [at] 4:30 in the afternoon. I walked in, [and I] hadn’t slept for a few days, for travel reasons. I guess that informed it… [Jim also] read with me, which is very rare. When you feel that somebody’s there, and wants you to be there, it can really open you up.

There was intensity all through that movie. But you were shooting in the middle of nowhere. When you weren’t shooting, was the camaraderie like the campfire scene in Blazing Saddles or did it feel like a group of Method actors trying to keep everything serious? Well, there was a great amount of camaraderie. My difficulty with the question is the word “Method.” That term has been really confused, particularly by younger actors, who take it as you’ve got to go sit in the corner by yourself for you to draw [upon] a truthful experience. Some of the guys who weren’t supposed to get along, didn’t get along. Some of the guys who weren’t supposed to get along, got along. The focus is razor sharp, the confidence is there and the preparation is there. They’re quick with a laugh, but if it’s before a big scene, or something that someone’s still exploring, everyone takes their own time to find it and then engage. I don’t know what the other guys were doing. I know I needed to take a few moments between takes and setups. I had to kill a bellboy in a hotel, and I had to keep it warm.

When you do two characters like Jake Mazursky in Alpha Dog and Charlie Prince in 3:10 in quick succession, do you have to be careful to play an entirely different kind of character next so you don’t get typecast as the angry guy? It’s always going to be material-based. I really enjoyed these [characters], but the interest in the sociopath isn’t calling me now as deeply as it has. You always curse yourself when you make these statements. If I say I’m not going to play another bad guy, tomorrow I’ll sign up for one. I’m aware of it, that everybody judges you on your last project. They think that’s who you are, and that’s fine. I got in this to be a lot of different people, and I really enjoy that. I take pleasure in working with different people, exploring different questions. So, yeah, if that’s all I’m offered, I’ll probably take a break for a while.

What do you do when you take time off? I like going up north, driving until I get tired and crashing out in a hotel. Seeing where the car goes. Reading a lot. [I spend a] lot of time by myself. It’s so important, to be able to hear the thoughts in your own head.

How important is meditation in achieving that? Supremely. One can do that any way they want. It can be basketball, taking a walk, playing an instrument — any kind of action that takes you out of your intellect and into the feeling level. It calms you down and allows enough space to hear what you are actually feeling.

You grew up in a household with parents who were devoted to Transcendental Meditation, and you’re a practitioner yourself. That makes you centered and calm. How do you summon the rage that made you stand out in Alpha Dog and 3:10 to Yuma? My goodness. Everyone goes about creating a character differently. It’s about making room for that person to come through. [What] keeps that from happening is [being] too crowded inside, and having too many preconceived ideas and being overcomplicated about it. That’s not to say one shouldn’t do a proper amount of research and prep before a picture, but for a real exchange to take place, one should be more a vessel. Neil Young once said, “The song already exists, just try to get out of its way.” I feel the same way.

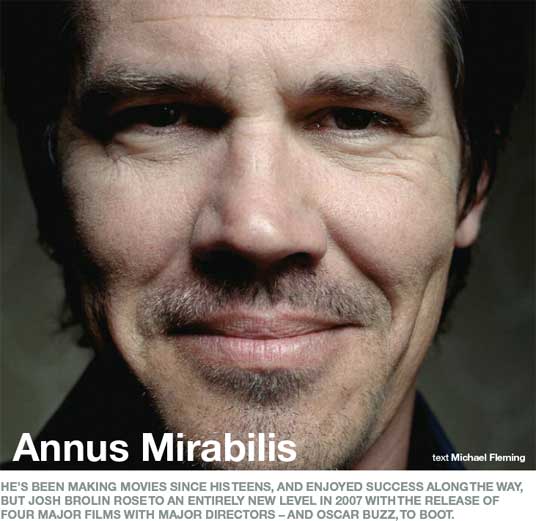

our career has spanned twenty years. But this year has been stellar, with not one but four films with high-profile directors: Planet Terror, with Robert Rodriguez; In the Valley of Elah, with Paul Haggis; American Gangster, with Ridley Scott; and No Country for Old Men, with the Coen Brothers. If you were a baseball player, they’d be testing you for steroids. How did this sudden second wind happen? That’s a good take on it. Well, I would test cleanly, and there has been no manipulation and no corruption, no nepotism. I have no idea how to account for this second wind. It was a snowball effect. Not that I haven’t worked with amazing people, and I’m proud of the people that I’ve worked with, but to do these things back to back was like serendipity.

our career has spanned twenty years. But this year has been stellar, with not one but four films with high-profile directors: Planet Terror, with Robert Rodriguez; In the Valley of Elah, with Paul Haggis; American Gangster, with Ridley Scott; and No Country for Old Men, with the Coen Brothers. If you were a baseball player, they’d be testing you for steroids. How did this sudden second wind happen? That’s a good take on it. Well, I would test cleanly, and there has been no manipulation and no corruption, no nepotism. I have no idea how to account for this second wind. It was a snowball effect. Not that I haven’t worked with amazing people, and I’m proud of the people that I’ve worked with, but to do these things back to back was like serendipity.

Before this resurgence happened, were you happy or frustrated with how your career was going? I felt absolutely fine and satisfied. Happy. I was never that actor who looked jealously at other people doing great work. There was a part, I won’t tell you what it was, but there’s a part that Mark Ruffalo is doing, that I was interested in. The fact [that] it’s Mark, not only do I totally understand, [but] I’m so happy it’s Mark. Not only is he a great guy, he’s going to be fucking fantastic in it. I’m happy about that. The only time I ever get tweaky about casting choices is when I go, “You’ve got to be kidding me! I know they only chose that guy because he’s the most valuable guy right now. The casting is wrong. He has bankability.” And that’s why I’m grateful to the Coens, because they cast how they saw fit, as opposed to who they saw as the most valuable at the time.

No Country was supposed to star Heath Ledger. How did Ledger fall out and you fall in? I’m not sure what that process was. I know they saw a lot of people; there were months of that. The only thing I know about that process in casting that role is, they thought it was going to be easy: an organic everyman. They felt, once they got Tommy [Lee Jones] and Javier [Bardem], that this would be the easy part to cast. Then it got more frustrating. At one point, Heath was interested in doing it, but dropped out, which he has a tendency to do anyway. He’d just had a kid, and I totally understand and respect that. They started meeting a lot of people, and I know a lot of them wanted to do it. After the audition [tape] I’d done through Quentin [Tarantino] and Robert [Rodriguez], they’d basically said no. My agent, Michael Cooper — thank God for him — said, “You just need to meet him. Just meet him.” I met them during their last casting session. By the time I got home, I found out they wanted me to do it.

How much did Robert and Quentin do for you? That must have been some audition tape. It was funny because it kind of bit me in the ass, the whole thing. It’s an amazing tape. Robert carries around a video camera a lot of the time, and I said, “This Coen Brothers movie came up, and I can’t leave.” He said, “I don’t mind, and why don’t we just use the camera we have?” — which was this Genesis camera, a high-end, million-dollar camera. So he set it up, he lit it and Quentin was there giving me line readings — that I didn’t necessarily agree with, but he was there, passionately, nonetheless. We did two scenes, Robert cut them together [and] sent it to the Coens, who said it was the best-looking audition tape they’d ever seen. “Who’s the DP?” They were more interested in the DP than they were in me. They said, “No. The tape is fantastic, Josh is great. We don’t know his work, but that’s not what we’re looking for.” But I was also a lot bigger, [and] I had a huge goatee. I didn’t look like [No Country for Old Men character] Llewellyn [Moss] at all. It wasn’t until we got together and had a conversation… I don’t think doing scenes in front of them at that point was even necessary. It was just having the conversation.

After you were cast, you crashed your motorcycle and shattered your collarbone. How close did you come to losing it when that happened? There was probably a ten-percent chance that I was going to be able to do it, at least from my perspective. I snapped my collarbone.

What happened? I was going about thirty-five or forty mph, and a lady pulled in front of me. I T-boned her, but luckily, I hit the part of her car where it was the back, and flew over the trunk. Had I hit her any sooner, I’d have hit the car with my body, and it would have been awful. I was lucky, but I snapped my collarbone, saw the X-ray and said, “This is not good.”

When this is going on, people say their life flashes before their eyes. Did the role of your career flash before your eyes? My kids were first. Then the Coens were second. The life wasn’t even in there. I don’t know why, but it’s kind of disturbing. Maybe I figured, “This is going to hurt, but it’ll be all right.” But I thought about the Coens, and remember thinking, “Shit, man, I really wanted to do this movie. Good role. Loved them. Ain’t gonna happen now.”

Whether it’s a woodchipper in Fargo, or Javier’s portable air compressor in No Country, the Coens have an evil sense of humor. Are they a riot to work with? It’s fun, but they are not a riot. They surround themselves with people who are fun and funny, and me, I mix it up. Javier mixed it up a lot, too. Ethan rubs his head, and he hums a lot. Joel kind of stares off into some creative distance. I’d sit there, and nobody would be saying anything, and I’d go, “Hey, guys, I just want to say you’re doing a great job on your first film. I just think you’ve got a long career ahead of you.” Thinking I’d get a fucking laugh out of them. But no, nothing. They just go back to humming and staring off into the distance, and I’m like, “Goddamn. Nothing! These guys give nothing!” But I get along with them very well. Ethan and I especially have a lot of laughs. They’re very easy, and there’s an incredible lack of ego on the set. Not a lot of compliments, which is hard to get used to in the beginning. As an actor, you want to know how you’re doing, if you’re going in the right direction and if you’re fulfilling their vision of the movie. After awhile, you say, “OK, I just don’t fucking need this at all. I’m just doing my job and that’s it.” But it was good.

They must have really connected with your character Llewellyn, who’s a man of few words. How difficult was it, establishing what to say and not to say? Is it harder to act when you don’t have the benefit of much dialogue? I didn’t realize it before I started working, but that was the biggest challenge. You have to convey these ideas without this crutch of dialogue. Can I do that? I was worried I’d overcompensate, or go vacant. I told them, “Please watch out for me,” so that, after I walked through the desert for the thousandth time, I didn’t take a trip to Tahiti in my head. Because you’d see it in my eyes, and when I’d see the final product, [I’d] be very disappointed in myself. Suddenly, without the music, without sound design or a lot of dialogue, everything else has a weight it doesn’t normally have. Grunts, scratching your face, the way you carry yourself — these become dialogues unto themselves. That was a worry for me, honestly. I wanted to be able to pull that off, stay present, but not overdo it.

A lot of actors subscribe to the Method. You and Javier were bitter rivals in No Country for Old Men, and you were making this movie in the middle of nowhere, where there was probably little to do when you weren’t filming. How’d you get on? It was the most fun I’ve ever had on a movie, bar none. Flirting With Disaster was the most tense I’ve ever been on a movie.

Why? Because comedy is so tense, man, and everybody is racking their brains over what is going to be funny or not funny. With No Country, the tension was there, in the script, and so you had to equalize in order to survive. We were hanging out at bars. We had bonfires all the time. There was one point, at three in the morning, the fire went out, and the crew, me and Javier were there, and there was no more wood. I go, “Javier, follow me.” [Dead-on Bardem impression] “Where are we going?” I go, “To find some wood.” He says, “No, man, I don’t want to do anything illegal. I don’t want to end up with me in jail or anything.” “Just follow me.” So I take him to some neighbor’s house, a quarter mile down the road. We’re looking for firewood in their yard. He was like, “Man, this is very scary for me.” He’s one of the most sensitive guys I ever met. Finally, we saw a fence. I put his arms out, and said, [whispers] “Be really quiet.” I started grabbing some of the posts of the fence. These poor people, I guess I owe them ten feet of fence. I put them in Javier’s outstretched arms, and I said, “Follow me.” He says, “Oh, this is really bad, really bad.” But that bought us another hour and a half of fire, so it was all good.

Did you ever get a sense of where his hairstyle came from? Tommy Lee Jones had given the Coens a book about turn-of-the century brothels or something. There was a guy in that book that looks exactly like Javier: the haircut, the clothes, the whole bit. We were working on my mustache; Paul LeBlanc, who’s an Academy Award-winning [makeup artist], was sitting there. Javier was to my right, getting the haircut. We were talking about what to do with my facial hair. They were scared that if I had a mustache, I’d look like one of the Village People. Javier goes, “Oh, my God!” I go, “What?” “Look at my fucking hair, man. This is horrible.” So we went out to this lesbian bar, Cowgirl Café in Sante Fe, and Javier was really depressed. I said, “What’s the matter?” He said, “I feel very bad about my hair.” I said, “You look fine.” “No, I don’t. I’m not going to get laid for three months.” Then I asked [him] recently, “Did you get laid?” He said, “Fuck no. Man, look at me. I look horrible. Fat.” He gained weight for it, and that haircut. Anyway, we had a ball.