You don’t get a second chance to make a first impression. Yes, it’s a cliché, but not without reason. After all, with filmmakers, the debut feature can set the tone for an entire career.

You don’t get a second chance to make a first impression. Yes, it’s a cliché, but not without reason. After all, with filmmakers, the debut feature can set the tone for an entire career.

But what about the very first time they committed image to celluloid? Whether made at film school, a news bureau, or around the neighborhood with the help of friends, many of these maiden efforts show clear signs of the talent that would eventually emerge — although some are downright confounding.

Case in point: Orson Welles may have dazzled the world with Citizen Kane, but his first film, The Hearts of Age, a silent short made with school chum William Vance in 1934, is an unsettling eight minutes heavily influenced by surrealism, but hardly the bellwether of directorial genius.

On the other hand, Firelight, Steven Spielberg’s first film, made when he was seventeen, was a feature-length science-fiction drama involving UFOs and alien abduction — an obvious stepping-stone to later classics like E.T. and Close Encounters of the Third Kind.

What were other renowned directors inaugural films like? For some answers, Fade In scoured the filmic plains to unearth twenty similarly obscure artifacts of cinematic history.

Enjoy, but with some of these babies it would be wise to heed the warning of Mark Twain at the outset of Huckleberry Finn: “Persons attempting to find a motive in this narrative will be prosecuted; persons attempting to find a moral in it will be banished; persons attempting to find a plot in it will be shot.”

David Lynch

Six Men Getting Sick (1966)

What can you do in one minute? Well, if you’re a twenty-year-old David Lynch, you can disturb the hell out of people. Shot while he was attending the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Art, this is an animated film that Lynch built on a sculpted screen, a strange hybrid of sculpture and painting, all set to the incessant wail of a siren. The gist: Six heads grow arms, stomachs, catch fire and vomit. Made for a paltry $200, this was a clear signal that Lynch’s trademark weirdness was a force to be reckoned with. Highly recommended for watching with pharmaceuticals.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=t04j0qX4-lI

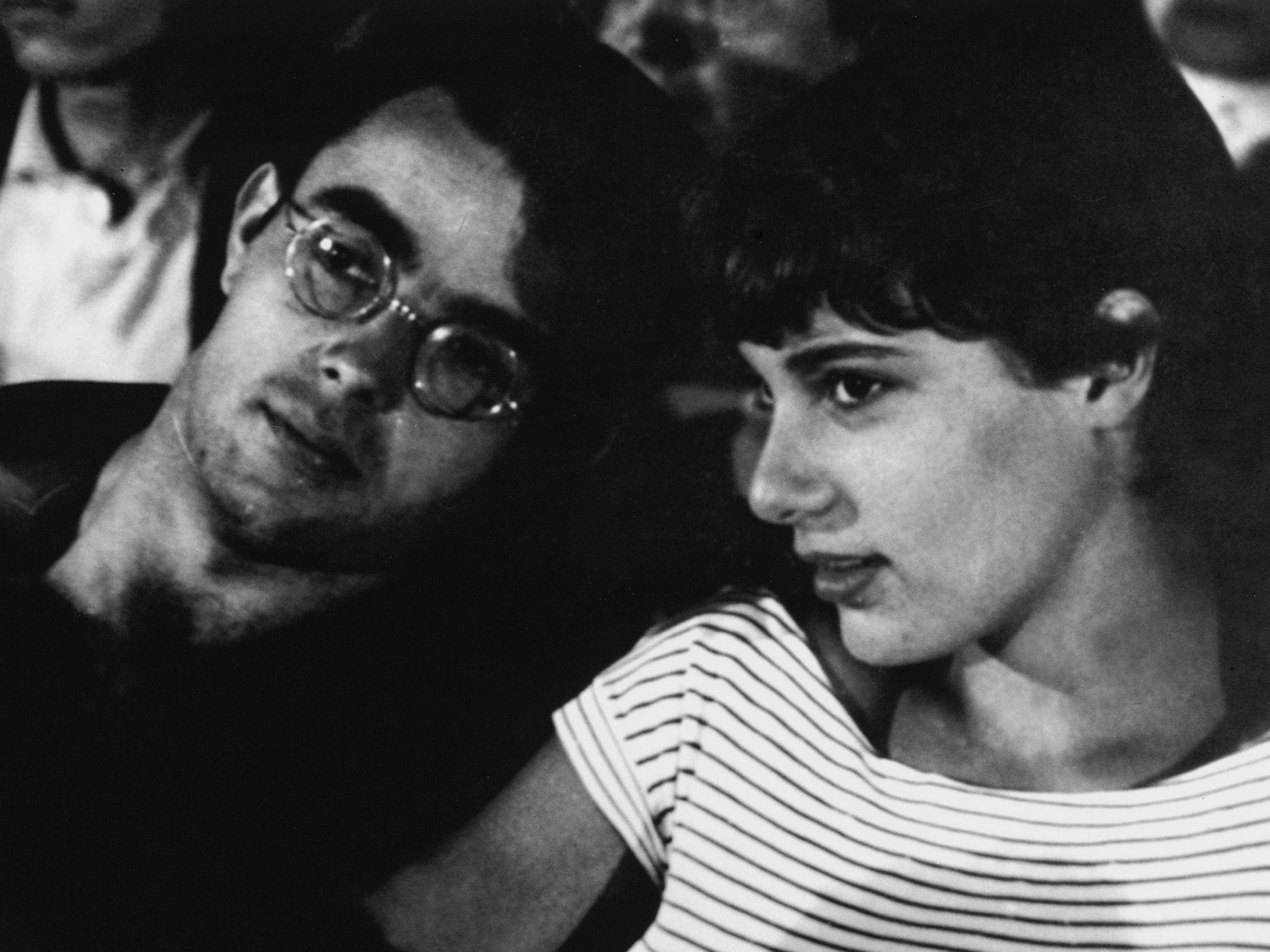

Francois Truffaut

Les Mistons (1957)

Okay, technically, this is the second film Truffaut made after his stint as a critic at Cahiers du Cinema, but he never released Une Visite, which he only showed to his friends. Les Mistons (The Brats) is pure French New Wave, as it follows a group of young boys who aim to disrupt the summer romance between a beautiful young woman and her boyfriend. Although Truffaut was still two years away from The 400 Blows, his landmark feature debut, this short is a perfect warm-up act with its examination of disaffected youth, and shows that a major talent was about to be announced to the world.

Quentin Tarantino

My Best Friend’s Birthday (1987)

In Q.T. lore, the story of this film is legend. Made while he still held his day job as a video store clerk, the film took four years to make, and was originally much longer, but because of a fire he wound up with only thirty-six usable minutes. Long stretches of quippy dialogue, liberally sprinkled with pop culture references and profane humor, all highlight this shaggy dog tale of a birthday gone wrong. The story is so disjointed that all you take away is Tarantino’s turn as a hyperactive DJ, but all the seeds are sown for his eventual style. Because of the lost footage, the film just kind of ends, not adding up to a whole lot, but in the history of Tarantino’s oeuvre, purists know this is where it all began.

Wes Anderson

Bottle Rocket (1994)

Anderson used his offbeat approach to storytelling as a calling card with this 16mm, thirteen-minute version of what would become a full-length feature two years later. Because of a miniscule budget, Owen and Luke Wilson, rather than known actors, had to play the leads. The loose-limbed plot about a couple of guys who may be the most laid-back robbers ever, relies on naturalism and improvisation to carry out the meandering saga. It’s no wonder Anderson took this to Sundance and got people interested, relying on the wit and charm that have helped turn him into one of our most idiosyncratic talents.

Lars von Trier

The Trip to Squash Land (1967)

At age twelve, long before he added the “von” to his name (and extolled the virtues of Hitler), in 1967 the disagreeable Dane came up with this stop-motion, two-minute animated tale of a sausage that dances with what looks like head-popping rabbits, while a pop ditty plays. Don’t ask. It makes no sense. What makes it interesting is the abrupt ending — spoiler alert! — where the sausage, rabbits and a giant whale disappear inside what looks like a big green house and the word “SLUT” pops out. Okay, don’t get too excited. Slut is the Danish word for end. Shame on you.

Christopher Nolan

Doodlebug (1997)

Before all you Nolan fanboys start bombarding us with hate mail about this not being his first film…yes, we know. He did make Tarantella and Larceny prior to this, but try finding those to watch! More Lynchian in spirit than evidence of the brooding maestro that Nolan has become, Doodlebug is a three-minute short about a man trying to track down an irksome insect annoying him in his flat. A great surprise ending punctuates this 16mm film, for which Nolan said they painted their own blue screen. It didn’t work very well, leading him to remark, “It’s worth paying for the proper paint if you’re ever faced with a similar dilemma.”

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=pWs1SM0xYiI

Martin Scorsese

What’s a Nice Girl Like You Doing in a Place Like This? (1963)

Light years away from the crime and mean streets that would become his domain, Martin Scorsese actually got all Buñuelian on us with his nine-minute NYU short about an obsessed writer. No one would’ve figured he’d try his hand at a wry, surrealistic comedy, that for the most part is deftly silly and fun. The nominal story finds the writer completely taken with a painting on his wall, turning his life upside down. Scorsese said he was inspired by the Mel Brooks animated short The Critic (a classic in its own right), but with the quick cutting and directing, it borders more on the avant-garde. In short, a textbook definition of “anomaly.”

Tim Burton

Vincent (1982)

Arguably the most visionary director of the last thirty years, Burton laid the foundation for what was to follow with this six-minute, stop-motion-animation short about a young boy who fancies himself Vincent Price. Of course, it helps when you have Disney backing your short to the tune of $60,000 and you even get the Vincent Price to do the narration, but Burton’s macabre humor and vivid imagination are the true stars here. The film is also a breeding ground in terms of characters and visual design for everything from Beetlejuice, to The Nightmare Before Christmas, to The Corpse Bride. Naturally, the studio didn’t know what to make of it at the time and eventually locked it away in that infamous Disney vault.

Terry Gilliam

Storytime (1968)

Of all the films mentioned here, Gilliam’s three-tiered, animated short is the only one that pretty much would fit in just about any timeline in the director’s body of work. It just happened to be his first, but it displays the same anarchic style that for years peppered his contributions to Monty Python. Flitting from the brief story of a cockroach, to Albert Einstein (no, not that one), to a crazed Christmas card, Gilliam’s madcap method of utilizing photos and animation was nothing short of revolutionary. There’s some debate as to when the short officially came together, as the segments were split up on British television, but whether broken up or assembled, it’s all pure Gilliamese.

Spike Jonze

How They Get There (1997)

After years of directing skateboard and music videos, Spike Jonze made a splashy entrance into shorts with this darkly amusing two-and-a-half-minute comedy. To the strains of “Sentimental Journey,” a guy and a girl trade flirtatious looks and gestures across the street from one other, with unexpected results. Not one to forget his roots, Jonze even cast “the godfather of modern skateboarding,” Mark Gonzales, as the guy. The production values are top notch, and as he has demonstrated in his feature career, Jonze is a director to whom the word “predictable” will never apply.

Werner Herzog

Herakles (1962)

Sometimes things are just too bizarre to resist, and such is the case with Herzog’s very first film, which parallels men working out in a gym with the labors of Hercules. In the film, made when he was twenty, Herzog poses onscreen questions that apply to Hercules’s challenges with what he intends to be contemporary equivalents (i.e., whether or not he will defeat the Amazonian women, matched to shots of women parading in uniform). It’s obvious he’s lampooning the whole macho myth (underscored with a lively sax performance), but this is truly off the rails. Running a scant nine minutes, it has to be seen to be believed.

Steven Soderbergh

Winston (1986)

Three years before he shattered the myth that art-house films can’t be commercial with his first feature, sex, lies, and videotape, Soderbergh made this fourteen-minute, black-and-white short about sexual jealousy. Touching on themes he would expand on in sex, lies, and videotape, Winston is set in motion when a woman mentions to a potential suitor that he may have a rival. Paranoia and jealously ensue. Although the actors are a bit wan, the direction and screenplay show undeniable potential. Winston is reputed to be the film that helped Soderbergh score investors for his Oscar-nominated debut. If so, it was money well spent.

Robert Altman

Modern Football (1952)

Who would’ve imagined one of American cinema’s greatest iconoclasts would start off by making a football training film? While living in his hometown of Kansas City, Altman cranked out countless industrial films, but it all began with this twenty-six-minute short. The majority of the running time is devoted to the rules of the game, but there are five minutes or so about a dweeb who dreams of making the team that are priceless ’50s cheese. The back story on how this film was unearthed is even better — it was purchased for ten dollars at a flea market! Debuts don’t get any more humbling than this.

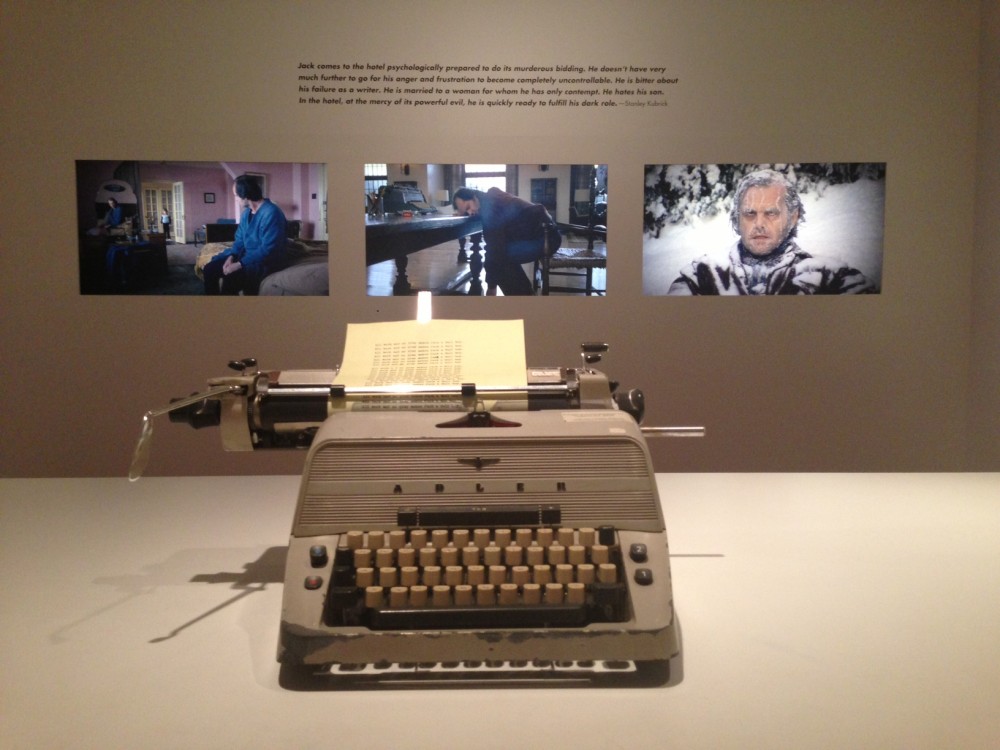

Stanley Kubrick

Day of the Fight (1951)

Like Altman, Kubrick’s first film was a decidedly unlikely foray into the sporting world— a sixteen-minute documentary on boxing. Included as part of the This Is America film series, it follows a middleweight boxer on the day of a big fight and is mundane, to say the least. Kubrick based it on a photo shoot he had done two years earlier, and the newsreel approach he takes does hint at the visual style and compositions he would later employ in films like The Killing. What is most interesting is that, despite some well-shot, exciting footage of the match, the narration is so anti-boxing that it renders the whole concept moot. Then again, Kubrick was nothing if not a master of irony.

James Cameron

Xenogenesis (1978)

Long before he became King of the World (and the box office), James Cameron was just another aspiring technology-obsessed wannabe filmmaker with a dream. He partially realized it with this twelve-minute short, made for $20,000, that showcased his ability to depict robots beat the living shit out of each other, as a guy and girl battle mechanized mayhem inside what looks like a giant grid. The robot action isn’t bad, showing a knack for action that he would later perfect with both The Terminator and Aliens. And, as with so many Cameron films, the script is an afterthought. Still, as rudimentary as it may be, Xenogenesis is an important touchstone for what was to follow in his growth as a filmmaker.

Ridley Scott

Boy and Bicycle (1962)

Hands down the most accomplished film of this group. Scott directed it five decades ago when he was a twenty-five-year-old photography student at the Royal College of Art in London. Heavily influenced by the “kitchen sink drama,” which pervaded so much of British cinema at the time, the film follows a boy (Ridley’s brother, Tony) pedaling around a dreary coastal town, reflecting on his life and observations in a stream-of-conscious narration. The great composer John Barry was so taken with Scott’s directorial chops that he kicked in an original score. Naturally, being a photography student at the time, Scott delivered striking visuals, a trademark of his remarkable career to this day.

https://vimeo.com/50606084

Jane Campion

An Exercise in Discipline – Peel (1982)

Many get their first chance at directing while still in film school. But how many win a prestigious Cannes Film Festival award, as Campion did with her debut short, which copped the Short Film Palme d’Or (and making her the first woman to ever do so)? While attending the Australian Film and Television School, she came up with this nine-minute film about a brother, his sister and the brother’s bratty son, who pull off the side of the road due to the boy’s obstinate behavior. A psychological war of wills ensues, with no resolution. If ever a film was a precursor to later work, it’s this, which is almost a kissing cousin to Campion’s 1989’s feature film debut, Sweetie, with its underpinnings of family strife and strident individuals.

Oliver Stone

Last Year in Viet Nam (1971)

In 1971, while enrolled at NYU and encouraged by film professor Martin Scorsese, Stone made this twelve-minute short about a decorated Vietnam vet wandering around New York City and ultimately chucking his meritorious awards for service. Intercut are flashbacks to the jungle, an inspirational score and a French woman narrating throughout the film. Pretty simple stuff, but obviously very close to Stone, who served a tour of duty in Vietnam in 1967. There are certainly early echoes of Platoon in the film, and it does have that late-’60s-early-’70s counterculture feel, but it’s also the one American film on this list that is content to make you feel, rather than seeking to impress.

Robert Zemeckis

The Lift (1972)

Another USC film school alum, and the director behind the Oscar-winning Forrest Gump, made a striking debut with this Twilight Zone-esque tale of a businessman whose life begins to spiral out of control when the elevator in his apartment building starts to malfunction. Shot in black and white, with a smooth jazz score, the film is notable for its compositions and Zemeckis’s narrative economy — telling a complete story in seven minutes. Along with Lucas, Zemeckis was among the earliest talents to emerge from USC, which has produced a staggering roster that amounts to a who’s who of Hollywood.