I arrive at Central Park, and then at the diamond-shaped patch of earth, framed by oaks and footpaths, that I have selected after days of deliberation. In the gathering dawn, I see a series of disturbing things. Thing One is our 1st AD, Tom Fatone, looking at me with an expression that says, “We’re fucked.” Thing Two is our location manager, Kurt Enger, looking at me with an expression that says, “I’m so sorry.” Things Three through Twelve are immense, perfectly semispherical mounds of earth that have arrived here since yesterday and now cover my dream location at regular intervals. Were the film about motocross, this would be okay. But it isn’t, and it isn’t. I don’t know why the mounds are there, or who brought them. I will never know. None of us will.

“THIS IS SHOOTING IN NEW YORK,” somebody says, as Kurt speculates about park maintenance. I cannot believe it has begun this way. I remember that the crew does not know me, that I am that most fragile of things, a “tyro helmer,” and that it is important to instill confidence. So I laugh. Then Tom laughs, then Kurt. Together, laughing like idiots, we wander off to find another diamond-shaped patch.

Which we do. There, we begin to shoot a scene crucial to the story in which Anton Yelchin plays baseball with the French children of the woman he loves. We are halfway through the coverage when it begins to rain, AT FIRST LIGHTLY, THEN LIKE A MONSOON. We take an early lunch, during which the rain only intensifies. In the director’s trailer — actually an 8 x 6 x 6 aluminum box with a bench and a toilet — I learn that we cannot finish the coverage because the patch of earth is now a shallow lake.

We have the crew for four more hours before going into overtime, and I will be damned if this shoot starts with an unmade day. So we drape everything and everyone in plastic, and head back into the floods to shoot an improvised walk-and-talk with Anton and Bérénice Marlohe, his character’s beloved. I have no idea what they will say or if it will be any good or if there will be any place for it in the movie.

Anton and Bérénice are champions. They walk and talk through the rain, under umbrellas. Anton comes up with a line about the loss of his character’s virginity, and Bérénice runs with it. Arnaud Potier, our DP, shoots it long lens from 150 feet, through dripping trees. I’m struck by the effortless beauty and romance of Central Park, even under these conditions.

The little rain scene will become one of my favorite moments in the movie. The next morning, our editor, Matt Maddox, will cut together the baseball scene so that I never miss the unshot angles. For about a week, my legs will be bluish from the bleeding dye of my jeans.

It’s the perfect first day. It’s Ext. Manhattan in a capsule.

At our budget level, it’s impossible to shut down even a small section of 5th Avenue or its sidewalk. We will rely on luck and a platoon of eight souls — ADs, PAs and interns — who will be charged with keeping any and all upstaging elements out of the shot. It’s a job for eighty.

Take 1 begins. Anton and Bérénice are doing beautifully. Costume designer Heidi Bivens has dressed her in a manner utterly Upperly East Side. Arnaud keeps his frame painterly as the scene unfolds.

They’re five minutes in. We’re going to get it, think I, and on the first take. I have visions of being ahead of schedule. There are only a few more lines.

Then, on the monitor, I see A SMALL AMERICAN FLAG come into the bottom of the frame. The flag is attached to a stick, and the stick to a recumbent bicycle piloted by an elderly woman in a helmet. She’s headed directly at our actors at a remorseless rate of speed.

Anton and Bérénice become aware of her. They’re stealing glances in her direction, as any sane people would. They’re loath to break formation, but at the last moment they separate. The recumbent bicyclist shoots between them, then as now completely unaware of what she has done, and continues uptown.

No problem — we’ll go again. I walk the actors back to the starting point, offering what I hope are soothing words. Somehow, Anton and Bérénice are not sweating. I’m drenched. I run back to the camera position. We wait for the pedestrian traffic to clear a little, and then we begin.

We’re three minutes into Take 2, and it’s going well. Until a man, fiftyish, easily 6’ 4” and 280, wearing shorts and a polo short of brilliant orange, slips through our dragnet and positions himself directly between the camera and the actors. It’s a rare full-actor eclipse. And, as with its astronomical cousin, I cannot watch with the naked eye.

Another walk back to 1, more words of comfort, another sprint. Another take. Birds this time — pigeons, squadrons of them. Busses belching. A deafening siren from a passing ambulance, which will perhaps be returning for me.

Julie Lynn, one of the film’s two producers, yanks the telephone plug out of her ear — I’ve never seen her do this before — and joins the ranks of the interns. She’s heroic, but there’s just too much ground to cover. On the next take, a man walks into the scene, sees the camera, makes a FLAGRANT GESTURE OF APOLOGY, and goes back the way he came. We’ll go again.

The sun crosses over from camera right to camera left. The light is actually prettier at this angle, we realize, because the tree-cover filters it and you can see several different shades of green. We protect ourselves with two takes from a trailing Steadi in case we never get the long shot in one piece.

Then there’s Take 7. No one walks through the shot. No one drives through the shot. No one is rushed to the hospital during the shot. There are birds, but they’re charming. There are bogies, but you don’t notice them. There’s a bus, there’s some construction noise, there’s the squeal of brakes, but these things will be subdued by our sound designers, Zach Seivers and Justin Davey. Anton and Bérénice are at their very best, and the colors are the richest of the day.

The scene ends. In the movie, it will play as a casual oner.

To get it, I’m breaking two rules — rules taught to me as a young man, common-sense rules, rules you should never break. Rule 1: Don’t shout at night in wealthy neighborhood unless something is really wrong. Rule 2: If you must shout, DON’T SHOUT IN A LANGUAGE YOU REALLY DON’T SPEAK VERY WELL. Out of the corner of my eye, I can see Arnaud laughing and cringing at my grammar.

Thankfully, the children know what I’m trying to say, and they do it. The wildly wealthy neighbors do not complain, and the police do not come. Ultimately, the shot will play for three seconds.

In order for the backgrounds to seem compatible when we cut from Lambert’s coverage to Anton’s, we need to be going at a fairly constant rate of speed. We’ve been at it for two hours without success.

Inside the BMW, the air conditioning has been turned off because its hum is ruinous. I do not wish to speculate about the cabin temperature. But Lambert is as elegant in real life as he is on the screen, and he’s not sweating, either. We shoot until the last possible moment, at which point Lambert climbs off the process trailer and gets directly into his airport car.

The performances are superb, but nothing matches. In the edit, the car appears to alternately slam on the brakes and floor the accelerator. But Matt will build temp visual effects in the Avid using the real side-and-rear window footage, which will fit precisely and have all the correct shadings and spatial relationships. Artery, our visual effects house, will refine them. Effectively, it will be a green screen without the shortcomings of a green screen. In the movie, it will look all of a piece.

Lambert’s car escapes to the east, and he makes his flight.

As we work, it begins to rain. Heavily. We shut off the rain machines. You can’t tell. The wind kicks up. Later, I’ll learn that this is the beginning of TROPICAL STORM ANDREA, which has made landfall in Brooklyn in the middle of our scene.

Anton and Bérénice don’t mind; they’re terrific. The umbrellas, though selected more for style than strength, refuse to bow. The wind helps the comedy, the gray skies gives us just the light we want, and the swirling, airborne water lends privacy we could not have manufactured. Arnaud is ecstatic. Sound is a problem, but Justin and Zach will solve it with some deft ADR.

We get the scene. I go the men’s room. When I return, Andrea has taken the gloves off. She is torrential, and just about everyone is gone except director’s assistant Jeff Collins and wardrobe supervisor Catherine Crabtree. There are no taxis in this part of Brooklyn on a bright sunny day, let alone in the middle of a meteorological event. Calling a car service is foolhardy. We stand in shredded ponchos as I scan the area for the elevated subway platform, assuming that if we follow it we will eventually come to a station.

Twenty minutes later, as we wander under the El, a very kind taxi driver passes us, astonished. He gives us a long look, satisfies himself that we are no threat, and takes us back across the river. In the cab, our expressions of gratitude lead to easy conversation. He tells us that his son wants to be in the movie business, and asks if I have any advice he can pass along. I say, “ALWAYS HAVE A RIDE HOME.”

Julie Lynn and fellow producer Bonnie Curtis are the first ones on it. Together with everyone available, we move the garbage bag by bag until the frame is clear. We finish the martini shot actual seconds before our clock runs out. In the film, you see only Anton, the sidewalk and the Dior lights.

The scene involves a monologue delivered by Olivia Thirlby, who plays Anton’s best friend and editor. It carries a major story point and needs the tension of a sustained, fluid shot. I want to try for it in one, with a leading Steadicam.

I describe the shot to our Steadicam operator, George “Steady G.” Bianchini.

“So, George,” I say, “walking backwards, you’re gonna lead Olivia and Anton down this long hallway, make a backwards left, lead to them to the stairway, make another backwards left, go backwards up this flight of stone stairs, make another backwards left, go backwards up this other flight of stone steps, do-si-do to let Anton and Olivia pass you, follow them up that other flight of stone steps, capturing the beautiful ceiling on the way, level off, hold at the top, and then trail them through those 150 extras until they reach Eric Stoltz, where they’ll all have a conversation.”

HE LOOKS AT ME LIKE I’M OUT OF MY MIND. He asks gently if it might not be wiser to break the shot up into several smaller shots. It surely would be, but there isn’t time, and really the oner does serve the story better. I ask him to give it a try and, George, who loves a challenge, agrees. We spot a parapet above the midsection of the proposed path, and Arnaud mounts a second camera so that we can go between takes, if necessary. Olivia, who knows her one-and-a-half-page monologue down to the syllable, stands ready. Upstairs, the extras are in position, and Eric is all set.

But it’s not that simple. The Library, a Beaux-Arts masterpiece, was built in 1897, and nothing lasts for 116 years, stands several stories tall, has fifty-three-foot-high ceilings and holds thousands of tons of books, unless it has very thick, strong, walls and floors — in this case, made of Vermont Marble and brick. No video signal will pass through the stone, and no wire will be long enough (or easily enough kept out of the shot) to feed a monitor. Which means that in order to actually see what George is shooting, Arnaud, video assist Neil Bleifeld and I will have to backpedal behind George, all wired together, Arnaud clutching a small monitor. I HAVE NEVER IN MY LIFE BACKED UP THREE FLIGHTS OF STEEP STONE STAIRS, LET ALONE MADE BACKWARDS TURNS, LET ALONE CHAINED TO A FRENCHMAN, AN I.A.T.S.E. MEMBER AND A CAMERAMAN WEARING SEVENTY-FIVE POUNDS OF STEADICAM. If we go too slowly, George will back into us. Too quickly, and we’ll yank him. And this is assuming no one so much as stumbles. I’m not expecting much from Take 1. I’ll be thankful if nobody falls down the stairs.

We begin. Olivia is great. Anton is great. George is great. He backs into his first left turn — no problem — the three of us taking little backwards baby steps behind him LIKE MISMATCHED MEMBERS OF SOME REJECT CORPS DE BALLET. We all make the second turn and mount the first set of stairs. It’s easier than I thought. Olivia hasn’t missed a word.

We make the second reverse-turn and head up the second flight. George has them right where he wants them. Arnaud, Neil and I have established a certain synchronicity of step. I actually can’t believe it.

We do-di-do on the landing, backing up against the wall until George starts forward, then accelerating with him. Now we’re just walking fairly normally up the stairs and through the crowd, George and his trailing human centipede. Eric, who has been waiting patiently all the while, knows there is all kinds of pressure on him to secure this little miracle. He’s perfectly calm and nails his lines. We have the scene. Julie and Bonnie run out from behind an exhibit about Franklin Delano Roosevelt. Everyone hugs everyone. We get the hell out of there.

There is one more scene to shoot tonight. Bonnie leads the charge onto 42nd Street, where, in their car, Frank Langella and Glenn Close, who play Anton’s parents, will perform their last scene in the film. Such is the star power of these two people that even at this hour, a horde gathers on the sidewalk to watch. Glenn and Frank are perfectly comfortable. Their rhythm is gorgeous. They deliver the scene in the master, on the first take. It’s a vintage Arnaud Potier frame, with Anton in the backseat behind them, and it would be a shame to cut into it with coverage. Thanks to Frank and Glenn, I don’t even have to shoot the coverage. The day is made.

We run another take for safety and then they get out of the car. The crowd applauds. It’s three in the morning on their last day on the movie, and Frank has only one request: he wants to celebrate. Ten minutes later, our Talent Driver, Maya Bar-Lev, has Frank, Glenn, Anton, Bonnie, Julie and me in her van as she drives up a deserted Broadway looking for a diner that, Frank promises, is open all night and has amazing cheeseburgers and milkshakes. We find it.

Astonished nighthawks look up from their coffee as movie stars enter. Tables are pushed together, and for the next ninety minutes or so, we eat, talk and laugh. We have been awake for twenty-four hours, but nobody is tired.

Maya drops us all off. I walk the last few blocks to my little temporary apartment at 77th and York. The shoot is almost over, and I don’t want it to be. I don’t want leave my new friends. I don’t want to stop working with them. I don’t want to leave the city I love.

Nothing ever goes quite how you plan it here. Neither in filmmaking, nor in life. But if you keep your head up and your eyes open, The city will reward you. It will be rich, alive and beautiful in a way that no production can create. And you will count the seconds until you can do it again.

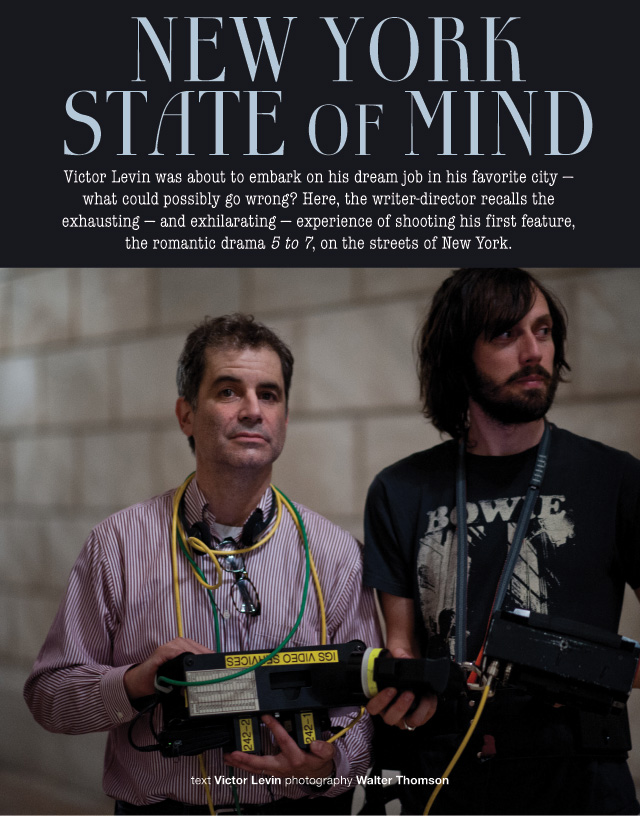

Victor Levin is the director and screenwriter of 5 to 7, which opens on April 3 in New York and Los Angeles, and in other cities and countries in the weeks following.