ove ’em or hate ’em, studio executives are an unavoidable part of the Hollywood filmmaking process, so producers, writers and directors have to learn to deal with them. Some regard “the suits” as helpful partners in that process. Others grumble that these very same folks do nothing but stand in the way, impede creativity and close doors. For some perspective, Fade In asked numerous, high-level, creative types to share their experience working with current regimes around town. Although we strove to balance comments, sometimes the negative would outweigh the positive, or vice versa, fueled by the anonymity that was promised to all who agreed to talk. But hey, don’t hold a gun to our heads — these are the producers, directors and screenwriters’ experiences, in their own words.

ove ’em or hate ’em, studio executives are an unavoidable part of the Hollywood filmmaking process, so producers, writers and directors have to learn to deal with them. Some regard “the suits” as helpful partners in that process. Others grumble that these very same folks do nothing but stand in the way, impede creativity and close doors. For some perspective, Fade In asked numerous, high-level, creative types to share their experience working with current regimes around town. Although we strove to balance comments, sometimes the negative would outweigh the positive, or vice versa, fueled by the anonymity that was promised to all who agreed to talk. But hey, don’t hold a gun to our heads — these are the producers, directors and screenwriters’ experiences, in their own words.

DREAMWORKS/DREAMWORKS ANIMATION

Screenwriter “DreamWorks animation is a dream. I worked with Damon Ross and he was so smart and so adept at the things that a studio executive should be adept at — which is truly understanding what makes a good structure, and making comments that really tuned that structure. It was a pretty ideal working environment. I found that every executive I met there seemed enthusiastic, smart and reverential of the writer’s job. Writing in animated movies, there is a much greater understanding of how the process works because it’s a really long process — years and years. If I really caught on fire with an idea or a storyline or character, they were willing to step out of the way and let me do that. And then I was able to deliver them stuff that is truly special, to present something that the audience has never seen before.”

Producer “I’ll tell you whom people fucking hate. In the last five days, I’ve talked to five different people, and all of them, independent of one another, hate [production head] Adam Goodman. They don’t trust him. He’s arrogant.”

Producer “I can’t believe Adam Goodman is still there. He’s one of those guys who will either pop out and get his own thing, or get squashed into oblivion. If [CEO] Stacey [Snider] wasn’t waging her own war with Brad Grey, and all of her energy wasn’t being focused on the outward enemy, he’d have gotten killed a long time ago.”

Screenwriter “Kira Goldberg, Adam Goodman and Stacey Snider are all great. It’s a very supportive studio. I’ve never worked at a studio with this much creative freedom. All three of them were just terrifically supportive. If you’re about to give your project to someone, I felt completely comfortable giving it to them. I felt they would protect it, I felt we shared the same vision, I felt they listened to the vision, and I felt we would have an input into who would be directing it — and we did. Their notes were not arbitrary to make it fit. They were very organic to the story. They give you parameters within which you should work, but at the same time, they’re first and foremost about the story.

Screenwriter “Kira Goldberg, Adam Goodman and Stacey Snider are all great. It’s a very supportive studio. I’ve never worked at a studio with this much creative freedom. All three of them were just terrifically supportive. If you’re about to give your project to someone, I felt completely comfortable giving it to them. I felt they would protect it, I felt we shared the same vision, I felt they listened to the vision, and I felt we would have an input into who would be directing it — and we did. Their notes were not arbitrary to make it fit. They were very organic to the story. They give you parameters within which you should work, but at the same time, they’re first and foremost about the story.Screenwriter “Stacey Snider is great. When I signed on to do a project with her, I didn’t really know her, so she brought me in for lunch — not to talk about the project, but just so she could know who I was. That impressed me. I feel that [with her there] it’s not just Steven Spielberg in charge of the studio. I feel like she really has control over the movies they’re making.”

Screenwriter “I never felt Adam Goodman had control of the reins. It was more like he was filling a seat until somebody else came in. I haven’t been blown away by him.”

FOX SEARCHLIGHT/FOX ATOMIC

Producer “[Atomic] is continually grinding out crap that makes no money, and yet they keep being touted like they’re these really smart, really tasteful, really successful people who’ve revitalized these labels. And you go, ‘I’m sorry?'”

Screenwriter “[Fox Atomic production president] Debbie Liebling’s really smart, and really great with comedy. There are very few executives I feel really understand comedy, and Debbie is one of them.”

Screenwriter “Even though he’s probably evil to the core, [Fox Searchlight President] Peter Rice is one of the smartest executives I’ve ever worked with. He’s someone who genuinely understands the mechanics of storytelling, knows a good line from a bad line, knows how to aid the process and you can see that reflected in their movies.”

Producer “It’s complete chaos at Fox Atomic. Rice is incredibly indecisive about their movies because he doesn’t understand them. They don’t reflect his own taste. The division is also underfunded. They’re making Playboys for $5 million. Since when are the studios into producing $5 million movies? It’s a piece-of-shit project with this comedy troupe the Whitest Kids U Know, who are funny. But the script is nothing. Rice hated the movie. Originally the budget was like, $8 or $10 million, but he said, ‘Well, if you can make it for five, I’ll do it.’ Why even be in that business? They should go make it as an independent film for $5 million and sell it to the highest bidder. It’s going to wind up going straight to DVD probably. Any movie they make, they grind the price down so much it’s almost not even worth making at that price, and it’s not even a studio movie anymore. It’s one thing to have a lower-budget division, but what should that mean? It should be $10-to-15-million-dollar movies, not $5 million movies. Half the movies at Sundance are $3-5 million. It was Rice’s idea to create Atomic, to create this youth division. The problem is Rice’s tastes are more sophisticated and adult. Danny Boyle is the filmmaker he discovered and made his reputation on. He doesn’t get youth movies, he doesn’t get youth comedies. He doesn’t know shit about comedy in general. He had this idea for a division — which might not have been a good idea to begin with — but it’s a division making the kinds of movies he doesn’t go see, doesn’t understand and doesn’t appreciate. So he can’t make up his mind about anything over there. He either says ‘yes’ to something, and then says ‘no,’ or he says ‘yes’ to something, and then, when it gets into production, he immediately starts to hate it. Or when it’s done he hates it. He doesn’t trust his instincts about it because he knows that he doesn’t understand those movies. Liebling is running that division, but he’s not letting her pick the movies.”

Producer “It’s complete chaos at Fox Atomic. Rice is incredibly indecisive about their movies because he doesn’t understand them. They don’t reflect his own taste. The division is also underfunded. They’re making Playboys for $5 million. Since when are the studios into producing $5 million movies? It’s a piece-of-shit project with this comedy troupe the Whitest Kids U Know, who are funny. But the script is nothing. Rice hated the movie. Originally the budget was like, $8 or $10 million, but he said, ‘Well, if you can make it for five, I’ll do it.’ Why even be in that business? They should go make it as an independent film for $5 million and sell it to the highest bidder. It’s going to wind up going straight to DVD probably. Any movie they make, they grind the price down so much it’s almost not even worth making at that price, and it’s not even a studio movie anymore. It’s one thing to have a lower-budget division, but what should that mean? It should be $10-to-15-million-dollar movies, not $5 million movies. Half the movies at Sundance are $3-5 million. It was Rice’s idea to create Atomic, to create this youth division. The problem is Rice’s tastes are more sophisticated and adult. Danny Boyle is the filmmaker he discovered and made his reputation on. He doesn’t get youth movies, he doesn’t get youth comedies. He doesn’t know shit about comedy in general. He had this idea for a division — which might not have been a good idea to begin with — but it’s a division making the kinds of movies he doesn’t go see, doesn’t understand and doesn’t appreciate. So he can’t make up his mind about anything over there. He either says ‘yes’ to something, and then says ‘no,’ or he says ‘yes’ to something, and then, when it gets into production, he immediately starts to hate it. Or when it’s done he hates it. He doesn’t trust his instincts about it because he knows that he doesn’t understand those movies. Liebling is running that division, but he’s not letting her pick the movies.”

LIONSGATE FILMS

Producer “I don’t think they take big chances on films. Once every indicator is positive, they’ll support it. [With our film], they thought it would [fit in a specific genre], and as they tested materials, and everything started testing through the roof, then they got behind it. When they’re tentative, they’re terrible. They dump things. If they don’t get [outside] assurance, they tend to be ineffective. That’s why they specialize in two fields — urban and horror — because those are easier genres to succeed in. When they get behind something, [Co-president of Theatrical Marketing] Tim Palen is excellent, and [former marketing exec] John Hegeman was excellent, but he’s now at Fox Atomic — which has its own set of problems. But sometimes people make the mistake of thinking that if someone is good in distribution, they can run a company.”

Producer “I don’t think they take big chances on films. Once every indicator is positive, they’ll support it. [With our film], they thought it would [fit in a specific genre], and as they tested materials, and everything started testing through the roof, then they got behind it. When they’re tentative, they’re terrible. They dump things. If they don’t get [outside] assurance, they tend to be ineffective. That’s why they specialize in two fields — urban and horror — because those are easier genres to succeed in. When they get behind something, [Co-president of Theatrical Marketing] Tim Palen is excellent, and [former marketing exec] John Hegeman was excellent, but he’s now at Fox Atomic — which has its own set of problems. But sometimes people make the mistake of thinking that if someone is good in distribution, they can run a company.”Producer “The production was probably the best experience I had on a movie. The reason is because they’re set up completely different [from other studios]. There’re two executives — the production president, Mike Paseornek, and the senior v.p. [of production and development], John Sacchi — and that’s it. And they’re doing the same job that a studio with fifteen executives is doing. Which means that once they greenlight the movie, they basically turn it over to the director and producer and they stay away from it unless there are problems and they’ve gotta get back in. Literally, it was the first movie I’ve ever done where I just did not talk to the studio all that much during the shooting of the movie. So the production side was great because they let the filmmakers make the movie. And as long as you hit your numbers, and they like what you’re doing creatively, they leave you alone. Now, the marketing side is a little different. They have so many movies, and so little staff, that they really go gung-ho two or three weeks before [the release date] and they don’t do long-lead planning because it’s not their motto, because they do [approximately] twenty movies a year.

You don’t have those long meetings that you have at Warner Bros. that are six months out, three months out. They really just focus on the two or three weeks [before], and they want controversy, and they want edge, and they want stuff that rises above the clutter. So that was surprising to me, because it’s not all that inclusive until the very end. And that sometimes doesn’t go with what the agents want and what the talent wants. But they just don’t have the staff [to operate differently].”

NEW LINE CINEMA

Producer “In the hierarchy of it all, I found the lieutenants in the marketing department at New Line to be very good; they worked very hard and did a great job for us. But I found all the top brass to be pretty checked out. I don’t even know if [Co-chairman/Co-CEO] Bob Shaye saw the final cut of our movie.”

Screenwriter “New Line is a highly, highly, highly dysfunctional family. [Certain] projects get a green light because of things like, for example, the head of distribution having a crush on Amy Smart, and saying, ‘If you put Amy Smart in this movie, I’ll support you in the room.’ It’s that kind of craziness. You don’t see a lot of people work with them multiple times. You don’t see natural follow-ups, like a sequel to Wedding Crashers, which any other studio would have mounted immediately, whatever it took. You’ll see gargantuan expenditures on things like Rush Hour 3 that weren’t warranted. Everyone has their own fiefdom, so no one is talking to anyone else; no one is internally supporting things. You’ve got [Co-chairman/Co-CEO] Michael Lynne saying, ‘Well, we’re going to go do Hairspray, and five movies aren’t going to get made as a result of that. We’re going to make Rush Hour, and spend three times as much money as we should, therefore a bunch of other movies aren’t going to get made.’ “I’ve never seen a studio have sixteen misses in a row and no one gets fired! Their core business, they don’t do. You didn’t see them do a sequel to Freddy vs. Jason, which made a lot of money. No, it’s not the Godfather, but anything that cost $20 million and made $80 million, any other studio would have made a sequel to. That’s puzzling. I don’t know how they justify things to their bosses. In the last two years, the chairman of the company was off directing a movie that the president of the company wrote. Think about that happening at Warner Bros. Think about Alan Horn directing a movie that Jeff Robinov wrote. If you just say that sentence, it sounds insane. New Line had something like nine movies that didn’t bust $20 or $25 million total gross.

Screenwriter “New Line is a highly, highly, highly dysfunctional family. [Certain] projects get a green light because of things like, for example, the head of distribution having a crush on Amy Smart, and saying, ‘If you put Amy Smart in this movie, I’ll support you in the room.’ It’s that kind of craziness. You don’t see a lot of people work with them multiple times. You don’t see natural follow-ups, like a sequel to Wedding Crashers, which any other studio would have mounted immediately, whatever it took. You’ll see gargantuan expenditures on things like Rush Hour 3 that weren’t warranted. Everyone has their own fiefdom, so no one is talking to anyone else; no one is internally supporting things. You’ve got [Co-chairman/Co-CEO] Michael Lynne saying, ‘Well, we’re going to go do Hairspray, and five movies aren’t going to get made as a result of that. We’re going to make Rush Hour, and spend three times as much money as we should, therefore a bunch of other movies aren’t going to get made.’ “I’ve never seen a studio have sixteen misses in a row and no one gets fired! Their core business, they don’t do. You didn’t see them do a sequel to Freddy vs. Jason, which made a lot of money. No, it’s not the Godfather, but anything that cost $20 million and made $80 million, any other studio would have made a sequel to. That’s puzzling. I don’t know how they justify things to their bosses. In the last two years, the chairman of the company was off directing a movie that the president of the company wrote. Think about that happening at Warner Bros. Think about Alan Horn directing a movie that Jeff Robinov wrote. If you just say that sentence, it sounds insane. New Line had something like nine movies that didn’t bust $20 or $25 million total gross.“There are stories of David Tuckerman, their head of distribution, literally banging on the table in the weekly staff meetings and screaming at the top of his lungs, ‘I cannot sell these movies foreign. You have to give me real movies I can sell.’ And them just saying, ‘Damn the torpedoes,’ and continuing to greenlight.

“Part of the problem is that you’ve got these guys with esoteric tastes. So they’ll say, ‘Oh, I don’t want to do a Freddy vs. Jason.’ In their mind, The Last Mimzy is high art. No one’s begrudging them for making a Terry Malick film [The New World]. That’s a rare thing. But when you’re making eight or ten or twelve completely small, indulgent films that should be made for $7 million to $10 million, and they’re spending $40 million to $60 million and they all bomb out…

“There’s a guy there, [Senior Executive V.P./COO] Richard Brener, who’s very sharp and knows a lot of stuff, and I can’t imagine that he won’t be running that place very soon. They lost a very sharp guy in [former executive] Jeff Katz, who knew the types of movies New Line made. He is a video game-playing guy;

he is a comic-book writer and reader. He is their target audience, and he’s not even thirty! Fox came in and picked him off. New Line’s lost key people that could have helped them. The worst part about [President of Production] Toby Emmerich is that he thinks he’s hip, he thinks he’s cool and he thinks that he’s got the pulse. There’s no evidence of the kind of shoot-from-the-hip [mentality] that once made New Line what it was. So it’s verging toward sort of a Short Bus family — that bad. It’s to the point where you see filmmakers and major producers saying, ‘I won’t make a movie at New Line.’ Will Smith won’t make a movie at New Line.”

he is a comic-book writer and reader. He is their target audience, and he’s not even thirty! Fox came in and picked him off. New Line’s lost key people that could have helped them. The worst part about [President of Production] Toby Emmerich is that he thinks he’s hip, he thinks he’s cool and he thinks that he’s got the pulse. There’s no evidence of the kind of shoot-from-the-hip [mentality] that once made New Line what it was. So it’s verging toward sort of a Short Bus family — that bad. It’s to the point where you see filmmakers and major producers saying, ‘I won’t make a movie at New Line.’ Will Smith won’t make a movie at New Line.”Producer “The executives are miniproducers just trying to get their movies greenlit by the studio head, being Toby. Even if they are fully supportive of the movie, and say they can get the movie made, that doesn’t mean they actually can. They’re not empowered to do anything. I didn’t get the sense that they had any authority to get something done. They can’t just say, ‘If you give me X actor, then we’ll go make the movie.’ They’ll say, ‘If you can give me X actor, maybe we can try to get the boss to say yes.'”

Producer “Bob Shaye has it set up where every movie’s gonna get made if the green-light committee says it’s gonna get made. So all these people have to weigh in on it. Toby’s gotta want to do it, David Tuckerman’s gotta want to do it, the head of marketing, the head of international, the head of home video, etc. And if one person doesn’t like the project, or it doesn’t work with his numbers, the whole movie can get derailed. It’s really frustrating for talent and agencies because you go ahead and make these offers, and they’ll put together the budget and directors — but they’re all subject to getting the movie greenlit. You can be in preproduction and if the green-light committee hasn’t signed off on it, the movie can get canned. You’ll find tons of stories where directors and actors literally thought they were shooting in eight or ten weeks, and it turns out the committee killed it. The agencies have a running conversation where they don’t believe it until the movie is actually shooting. And Bob Shaye set it up that way because he wants the checks and balances. It’s frustrating to Toby because he wishes he could just greenlight it. There’re probably a lot of movies he wishes he would have been able to do that [Shaye] didn’t let him do. So that’s the challenge at New Line. You never know if you’re going to make a movie until you’re actually shooting it because of the green-light committee.”

Screenwriter “Bob’s a character, but creatively I agreed with his notes. There’s an old-school thing about him. If you can see through the ‘Bob Shaye Show’ there really is an artist at work in there.”

Producer “Toby likes to pretend that he’s in charge, but he’s not — it’s really [distribution and marketing president] Rolf Mittweg. But Rolf isn’t really calling the shots, Bob Shaye is calling the shots. You will get notes from Richard Brener, and then it goes to Toby, whom you are told is aware of everything that you’re doing. But those notes don’t reflect Toby’s point of view. He’ll have notes that are completely different from the direction you’re going in.

“A big part of getting a movie made is trying to protect the integrity of what’s interesting to you about the movie with enough customization to get it made within that certain sensitivity. So you’ll be told that Shaye’s really excited about it, so you do the notes they ask. But Toby comes up with notes that lead you to believe that he never read the script in the first place. Then you go off and do those notes. Then you fight the battle with Rolf over casting. There’s no common ground in terms of casting that works for Toby, and casting that works for Rolf. But eventually you may or may not find a couple of names that, in order to make the offer, will get it done. It then goes to Shaye for his final blessing. Then the message comes back that he hates the idea and would never actually make this movie. That has happened to me twice, and it’s happened to others I’ve known a bunch of times. It’s OK to be shot down, and it’s OK to say, ‘Look this hasn’t gotten to him yet,’ but it’s almost like this game is being played, and for what purpose?”

“A big part of getting a movie made is trying to protect the integrity of what’s interesting to you about the movie with enough customization to get it made within that certain sensitivity. So you’ll be told that Shaye’s really excited about it, so you do the notes they ask. But Toby comes up with notes that lead you to believe that he never read the script in the first place. Then you go off and do those notes. Then you fight the battle with Rolf over casting. There’s no common ground in terms of casting that works for Toby, and casting that works for Rolf. But eventually you may or may not find a couple of names that, in order to make the offer, will get it done. It then goes to Shaye for his final blessing. Then the message comes back that he hates the idea and would never actually make this movie. That has happened to me twice, and it’s happened to others I’ve known a bunch of times. It’s OK to be shot down, and it’s OK to say, ‘Look this hasn’t gotten to him yet,’ but it’s almost like this game is being played, and for what purpose?”Director “Toby spends a lot of energy being hard to read rather than being creative. It’s all that ego shit. He has a supercilious or a haughty air when it comes to racial issues. It’s as though he’s never even thought about black people. It’s as if they don’t come into his strata. There’s an amazing story about [African-American director] Jeff Byrd [King’s Ransom], where he was in a meeting with Toby, and Toby said something so unbelievably racist. That is the lore. There were two witnesses in the room, and he said it in front of Byrd.”

Screenwriter “It’s Toby’s company, and he makes all of the decisions, and while other executives are sometimes involved, most of the bigger projects go through him. They are a strange company.

I find it really uncomfortable that they put their name on projects as producers. Shaye came in for one meeting to get up to speed on something. And while that’s fine, I always assumed that Toby was in charge, and then suddenly Shaye will show up, and it’s not clear who’s the most important person in the room.”

PARAMOUNT PICTURES

Producer “I’ve sat with [Chairman and CEO] Brad [Grey], who tells me that everyone there is an idiot. He’s a salesman. His thing is, ‘Hey, there’s a real opportunity here. There are basically no producers here who are any good.’ He’ll say whatever he needs to say, and then forget about it to try and get people [to work with Paramount]. [Paramount Film Group President, formerly Paramount Vantage president] John Lesher has Grey convinced that he has deep connections with all the agents in town. So you’ve got a manager, Grey, who’s basically promoting an agent, Lesher. None of them have actually accomplished anything. They’re both going, ‘Yeah, I like the way that guy talks on the phone. He’s good.’ It’s the one studio where everyone seems to hate each other. Nobody’s in charge over there. You can’t have that much rampant negativity and pretend that someone is in charge.”

Screenwriter “My interaction with various executives at Paramount has always been a little bit disparaging. There’s a weird close-mindedness to the point that I don’t think of Paramount when I think of going out with a script. Despite her star reputation, [Executive V.P. of Production] Pam Abdy, when I walk in the room with her, all I hear are reasons why it can’t be done. I’m made to feel like I should feel lucky to be in the room with her. It remains to be seen if any of those people should be in their position and Paramount acknowledges that by shifting people around all the time.”

Producer “[President of Production] Brad Weston is a joke. The guy doesn’t know anything. It’s that bullshit Zen attitude. He doesn’t lead, he doesn’t know movies, and he doesn’t know filmmakers. He doesn’t read. There’s no development. All his executives are running around with their heads cut off; they don’t know what they’re making, what movies they want to make. They are completely overwhelmed by DreamWorks. It’s pulling teeth to get notes, they don’t know what their brand is, they’re in competition from all sides. Scott Aversano [former president of MTV Films and Nickelodeon Movies] has a clear vision of what he wants to make; DreamWorks has a clear vision of what they want to make. And Brad is just floundering and spinning.

“The only projects that move forward are hugely expensive filmmaker-driven movies that Grey is interested in. Short of that, nothing’s going. You resign yourself to the fact that your project is dead until something changes there. It’s gigantic filmmakers driving projects that are marginal, like David Fincher doing Zodiac. They rely on huge deals like Lorne Michaels to drive through what those producers want to get made. Then they flop. Nothing’s made money. Brad Weston only trusts big filmmakers so he can rely on their expertise, not his own. He’s just lost.”

Screenwriter “I worked at Paramount with [Senior V.P. of Production] Dan Levine. Paramount is pretty bad for development. We were working on a very complex movie that required a lot of brainpower, and Levine was excellent. He was very sharp and eager to make the movie as good as it could possibly be. But then it would go to Brad Weston, where it would hit a wall of incomprehension, and we would get back these ridiculous notes that ruined everything we had done — not a thought as to why it’s been constructed that way, what it gives in terms of storytelling power and how it’s going to benefit the movie. Most of these comments just seemed so arbitrary, and in many cases, contradictory.”

Screenwriter “Paramount is a mess. I’ve worked on a number of movies at Paramount, and I believe it comes from the top. [Parent company Viacom CEO Sumner] Redstone likes instability in his executive branch. He doesn’t want anyone to feel too secure in their position. Every time I’m working there, the executives I’m working with are losing their jobs, or leaving. Nobody knows what’s happening, if that exec’s movie is going to get through, or if that exec will get axed before that movie goes through. I lost a movie there because they were firing [an exec]. [Former Co-president of Production] Alli Shearmur was always stabbing people in the back, jockeying for position and trying to destroy Brad Weston. One time, Shearmur called me into her office [about a project] and said, ‘I don’t understand the script.’ And I was like, ‘OK, first of all, you do. You’re just afraid the audience won’t understand it. You know what happens, how to answer any questions about anyone’s character motivations, how the story goes and how it turns.’ Then another studio decided to pick it up, a hot director signed on and before anything had been done to the script, Paramount called and said, ‘We’re not letting it go, and we’re exercising our option, and by the way, we hear the script is great.’ In the hands of a big director, it’s worth something; in the hands of a big writer, it’s worth nothing.”

Screenwriter “It was a disaster for me. First of all, they made a crazy deal on the project. It was a ‘let’s show everyone how much money we can spend’ [deal]. I just found that they weren’t helpful. And not only were they not helpful, they also created an atmosphere where you felt so in the cross hairs. It was incredibly difficult to perform. It’s like, if you don’t want me to do another draft, let’s figure something out and settle. All you have to do is say, ‘It’s not working, let’s move on.’ There was a lack of honesty. It’s not like the town is big, and we’re not going to be in a room together again. That’s gonna happen. So while it might be the end of us here, it may not be the end of us forever. If I were to say what separates a good executive from a bad executive, it’s the ability to sublimate your ego for talent. And at Paramount there was such arrogance, and such a competition between people who thought they were better than the other people they were working with. There was no room for talent because of the egos of everybody else. It was poisonous over there. You felt like you were being lied to. You felt like you were being set up. You were under the impression that you were working with people who work with you, but what you don’t realize is that you’re working with people who are working behind you.”

Producer “You’ve gotta wonder to what extent Pam has an easier time getting to make her movies. Maybe the rumor is true. Scott Aversano is the smartest guy over there, but Brad Grey [didn’t] let him make [anything] under $30 million with the MTV logo. He didn’t make a single movie [when he was] in charge of MTV. He had a $23 million Jonah Hill movie that Brad Grey wouldn’t let him make, a slightly oddball project called Psycho Funky Chimp. Here was Brad’s problem with it: They made Hot Rod with Andy Samberg, and it tanked, so he doesn’t want to make low-budget comedies anymore. But unlike Samberg, Hill has already been in a giant hit movie [Superbad]. And Brad doesn’t seem to get the distinction between Hill, who’s already a star, and Samberg, who wasn’t. Anybody in the business gets that. Grey is not letting his lieutenants make the movies that they’re passionate about making — even for a price. Paramount is horribly run. Marketing is tanking some of their better movies, but they’re still making too many shitty movies.”

Screenwriter “There’s not a standout executive there. There’s not a person that you understand, that makes you go, ‘Wow, that person’s gonna be running the studio.’ If they lose DreamWorks, it’s going to be very complicated. It’s odd, but they don’t draw down on their library. There’s so much stuff in that library that no one is making any use of. The way they handled Mission: Impossible — there’re like ten of those titles that are that big, and none of them are being accessed or used. That is crazy.”

Producer “Brad Weston strikes me as the kind of guy that’s full of shit, but doesn’t believe that he is. The same can be said about Emma Watts at Fox and Doug Belgrad at Sony. Brad is arrogant without portfolio. He’s that kind of executive that knows he’s right. In any business, you’ve got to beware of anyone who knows they’re right. Because generally they’re wrong.”

SCREEN GEMS

Producer “Mark Weinstock, their marketing president, is a genius; [President] Clint Culpepper is a jackass. Everyone at Sony wants to fire him, but the movies have been so successful that they can’t. The movies have been so successful not because of Clint but because of [Weinstock]. When we walked into the meeting, he didn’t know who the [high-profile] director was, he didn’t seem to know which project we were talking about and all he wanted to talk about was how drunk he got the night before — in front of people that he doesn’t even know! This Christmas had the number-one per-screen average opening weekend. It was a nothing movie, but the marketing guy did an incredible job, and it had a higher per-screen average than Enchanted [on opening weekend]. So it’s not because Clint is some kind of a genius. There’s no other reason to keep him in the job other than he’s had a successful run over the last few years. I saw he and [Sony Pictures Entertainment CEO and chairman] Michael Lynton fighting on the front steps of the TriStar building. I know Lynton hates him because I’ve seen them in a fight. Clint’s just a total loose cannon, and a creep.”

Director “Your respect is directly proportional to your irreplaceability. So in my case, if you come in with a project you have complete control over, you’ll be in fantastic shape and get exactly what you want. But I hear from other people involved with the same studio that they go through unmitigated hell. So far, the [preproduction] experience has been very good. I’m dealing with Clint Culpepper. He’s a smart guy, and he’s had so much success there, and he really has a level of right to be demanding.”

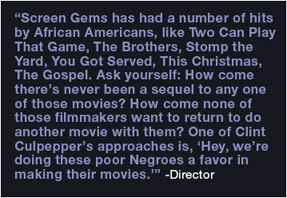

Director “Screen Gems has had a number of hits by African Americans, like Two Can Play That Game, The Brothers, Stomp the Yard, You Got Served, This Christmas, The Gospel. Ask yourself: How come there’s never been a sequel to any one of those movies? How come none of those filmmakers want to return to do another movie with them? They recently made a sequel to Two Can Play That Game called Three Can Play That Game. The sequel was awful, direct to DVD, people were walking out of it when they screened it and it was not made by any of the original filmmakers.

“One of Clint Culpepper’s approaches is, ‘Hey, we’re doing these poor Negroes a favor in making their movies.’ And even though ‘their’ movies make revenue, you don’t see a lot of these guys wanting to return to do business with him. The studio tends to overlook Clint simply because the movies make box-office revenue. Like, ‘Oh, that’s just the way he does things.’ Just because that’s the way he does things, the fact that he may violate certain creative rights of a director under the DGA, or a writer under the WGA, doesn’t make it right. He finds writers who want to direct, and those guys will do all of the writing under the guise of them directing the picture. He preys on first-time directors that are ignorant of their DGA creative rights. So they become victims, as opposed to him cultivating their talent and embracing them for what they bring to the table. And he will take credit for every good idea that you have. When you complain to the studio chief, or when you complain to your guild, they’re kind of like, ‘Oh, here’s another thing we’ve gotta deal with with this guy.’ So nobody’s not familiar with [his antics]. [Filmmakers] suffer his abuse because they want to make a film. But that doesn’t make them any less talented.

“[African Americans] want to make movies, but we want to be respected as well. Unfortunately, Clint is the only one making [urban] pictures. It’s the only place you can go to. When you only have one outlet to go to, if you can’t go anywhere else, you’re sort of caught in an abusive marriage. If you want to get your picture made, you know you have to suffer this guy in order to do it.”

Producer “Clint is a challenge, but he’s an extremely bright person. If the situation is that if you’re right, and you have to fight him to prove it, so be it. It’s when people are difficult and not so bright that it’s terrible. But Clint is one of those that is bright.”

Producer “Clint Culpepper is the most effective studio exec around. When he says he’s gonna make something, he goes ahead and does it — for better or for worse. He actually gets things accomplished very quickly. His downside is, he considers himself the director of the movies, and that can drive creative people crazy. Clint just does what he wants to do. However, I know that whenever I’ve brought writers in to meet with him, they’ve been very freaked out because of the way he presents himself.”

SONY PICTURES

Producer “[Chairman] Amy Pascal is an incredible micromanager, so that’s the biggest nightmare. Amy puts her stamp on everything, and it then becomes Amy’s movie, and that doesn’t necessarily make for good movies sometimes. She also has a huge problem in giving away the store, whether it’d be to [writer-director-producer] Judd Apatow or [producer] Jimmy Miller. Once she feels that a person knows more than her, then she completely trusts them, like [producers] Doug Wick and Lucy Fisher. They spent a shitload of money in development and made bad movies. Her hugely expensive deals — Jim Brooks, Nancy Meyers, Wick and Fisher — wind up biting her in the ass. [She does those kinds of deals] because she’s more of a manager than a real creative person. And now she’s done it with Judd, which is working out…right now.”

Screenwriter “The movie I worked on at Sony, I worked on with [production presidents] Doug Belgrad and Matt Tolmach. We pitch to Amy, and she always struck me as being a very smart person, an excellent businessperson and she has a pretty good track record. But the problem is, there is no respect for writers. The writing process itself — the studio executives all think they can do it. But with a director, that process is shrouded in enough mystery that they don’t feel qualified enough to step in.”

Screenwriter: “Amy has a definite point of view, and she treats me like a servant, like I’m the help.

She never lies to me. She’s never been mean to me. She’s supportive of me in the way she’s supportive of her help. That’s how she views me. I know Amy takes a lot of heat. Probably some of it’s deserved, but probably [some of it is] because she’s a woman. Like all major industries in America, it’s institutionally ingrained toward men. I find her genuinely unpredictable.”

Producer “Amy is smart. She’s the anti-Paramount. She gets the whole thing, and is not conniving, and actually cares about people’s feelings, which kinda puts her in a funky place. And she actually wears her heart on her sleeve, which is kind of a cool defense. Everyone there is to service her. Doug [Belgrad] and Matt [Tolmach] are really good. Doug’s fantastic. He’s really smart, and has surprisingly good story notes. And I say ‘surprisingly’ because you look at him and you think he’s a suit. Everyone is really honorable there, at least in my experience. [Sony Pictures Entertainment Vice Chairman] Jeff Blake is fantastic. They’ve got a fantastic machine. [Sony Pictures Entertainment CEO and chairman] Michael Lynton doesn’t get the credit that he should. It’s these guys who make it look easy. Brad Grey at Paramount makes it look really fucking tough, and that’s the difference. Amy has got everything buttoned down over there, and it’s very important that everyone get along and behave honorably.”

Screenwriter “Doug Belgrad was great; I would love to work with him again. He really understands story and has an easygoing and — for lack of a better word — a gentle demeanor. He is a very easy person to work with. There are people you work with that make you feel good about yourself, and people that you work with that make you feel bad about yourself. Doug is in the former category. He was very smart, and was very good with notes, and a real pleasure to work with. The only downside was — and you just have to accept this as a studio screenwriter — we sold it as a pitch, and once Megastar X got attached, I don’t believe there was ever any thought of keeping me on. It instantly went to Writer X. And that’s the kind of thing that you have to expect. I don’t blame Doug Belgrad. It’s just sort of the nature of the beast.”

Director With [former production executive] Emma Watts, there was no real concept of what the movie should be as a story, and no help in development in making it be anything. It was fear-based behavior. The movie ended up being made by Director X; they ended up doing a compromised version of what I was suggesting in the first place.”

Screenwriter “Everyone at Sony gets along really well, so you don’t feel that sense of territoriality that you do at other studios. Amy Pascal used to be waaaay too hands-on, and now she’s a lot less hands-on. Matt [Tolmach] and Doug [Belgrad] seem to work really well together. I wouldn’t say they are the most courageous, but they have a good sense of the type of movies they want to make. [Executive V.P., Production] Andrea Giannetti is honest, and even though she can’t always get you what you want, she’s very honest about what she can’t, and she’ll let you know what the internal politics are, which is crucial. You don’t always get that at other places. The downside is that sometimes they’re obsessed with the mass marketability of the project. I do have to say Doug Belgrad was relentless in pursuing me once, and that was really heartening. You do really admire people who are really dogged in their pursuit of getting something.”

20TH CENTURY FOX

Producer “Say what you want about [Vice Chairman] Hutch [Parker], but Hutch can put a movie together. That’s a big deal. [Co-chairman and CEO Tom] Rothman seems to think that everything is generating from his brain. And it’s just not. Yes, you can wind up Hutch, and when the winding has run its course, he’s done talking. But Rothman will bellow and bellow, and you’ll find very [little] talent who actually think his notes are good. People nod and smile and try to do what he’s asking because it’ll get their project made, but it’s not one of those things where you’re like, ‘Thank God! What a fantastic fucking note! You’ve actually made this better!’ All he sees is heads nodding, and stuff getting done, and he goes, ‘I’m a genius!’ If Amy Pascal had a bad run, and she lost her job, people would step in to try to help her. If that happened to Rothman, people would pull out their knives and it would be something out of a science-fiction film.”

Producer “[Co-presidents] Emma [Watts] and Alex [Young] are trying to kill each other, and they’re trying to kill Hutch, who promoted them, because they can’t help it. It’s the scorpion and the frog. Hutch has been marginalized as [vice] chairman, but Rothman is completely safe. [Co-chairman] Jim Gianopulos is fucking excellent at his job, and an excellent guy. It’s weird that Rothman usurps the fucking juice from that relationship. But Jim is really fucking good, and seems content just hanging back. I don’t think Hutch will be there much longer. He has been marginalized by being put off to the side. And I’m a fan of his. I like him. I want to make that clear. Emma and Alex are not leaders. At Sony, Matt [Tolmach] and Doug [Belgrad] made a pact that they will back each other completely. They speak as one voice, even though they split projects; they support each other. Emma and Alex are trying to kill each other, kinda like Alli Shearmur and Brad Weston did at Paramount, or not unlike Lorenzo di Bonaventura and Billy Gerber back in the day at Warners.”

Screenwriter “Fox is the quintessential example of what Tim Robbins is talking about in The Player: ‘If we can just get rid of these pesky writers and directors, we’d really have something.’ They feel that they are making the movie, and you’re there to copy down their ideas and maybe provide some snappy dialogue. That’s why I won’t work for them. I refuse to work for them because I’m not interested in being hired to be the world’s most expensive typist. It’s a Tom Rothman thing, it’s a [News Corp. President and COO] Peter Chernin thing, it’s a [News Corp. Chairman and CEO] Rupert Murdoch thing. It’s the corporate culture at Fox. The whole company is run with this incredibly arrogant attitude of ‘everything we say goes.’ If you’re putting up the money, of course, you’re entitled to have the projects go the way you want them to go, but the movies come out so horribly, in the end they shoot themselves in the foot. Fox has probably the best marketing in the business, but when they have a hit that makes $150 million, many times, had they had a better script, or even a coherent script, they could have made $250 million. It’s the inability to see the forest for the trees.”

Screenwriter “[Vice Chairman] Hutch Parker is the definitive empty suit. He doesn’t listen. He’s incapable of listening to you when you’re talking. Then, when he begins talking, he just talks, and talks, and talks, and there’s no substance. He’s not going anywhere. He’s talking to keep himself working; to keep himself looking busy. He’s like a politician. He can just talk, and talk, and talk without ever coming to a salient point. They’re all trying to stab each other in the back over there. Alex Young is just horrid — incompetent and arrogant. That’s really the killer combination.”

Director “I worked with Emma Watts, and she was cool. Rothman is like Big Daddy. When things go well, he’s right in there. If things aren’t going well, you never see him. Hutch is a really smart guy, clever, but doesn’t have the best sense of humor, so in terms of comedy, it’s a tired situation with him. He has a good sense of structure in terms of story. The thing I like about Hutch is that he’s not really verbose. He’s not a yeller or a screamer. He’s thoughtful. I just don’t know where he gets his taste from. I don’t know what he bases his decisions on. He’s Parker Stevenson’s brother, that’s what he is! People like Emma Watts kowtow to him. Emma’s smart, she has a good sense of structure, but she has a bit of a chip on her shoulder, and she — out of all the execs that I’ve worked with at Fox — is Hutch’s girl.”

Director“When you turn in your initial cut as a director, even if it tests well, there’s a tendency to still see it the way they want to see it. My film tested well, but they still wanted to test it again after they gave me their notes. They felt an obligation to see their notes tested. They don’t have faith in the public. They can’t believe a good thing. Once the public sees it, and it tests well, for some reason, they can’t accept that. They’re like, ‘Well, maybe this is the wrong audience because that thing didn’t work and we should bring in a whole new audience.’ They feel like they want to have their fingerprints on whatever goes out, no matter how small. The movies become chess pieces for them. They don’t really care if they’re good or bad. They told me they were pushing the release date of my film because the test scores were so high, but it was because one of their movie’s release dates was in conflict with another studio’s film, so they needed to change the dates. I felt like the sacrificial lamb because my movie ended up going against [the other studio’s tentpole] and I got buried. So once the movie’s done, it doesn’t matter to them if it’s good or bad. It’s basically a chess piece. It’s disappointing when they use your work as their business strategy.”

Producer “They’re a disaster. They think they are producers. They hate filmmakers, they hate producers, and they hate directors after the movie is shot. They think they know everything. It’s common knowledge that Tom Rothman hates producers. He’s very vocal about it. But they’re unbelievable marketers. Emma [Watts] and her crew and Alex Young and his crew — they feel they are the keeper of the flame, and directors are interchangeable. All their movies — they feel like they produce them. You’re totally marginalized. They just take it over. And you feel this tension between Emma and Alex. There’s a control thing going on internally.”

Director “The best marketing in the world is at Fox. They just take the material and know how to sell it. Their president of marketing, Tony Sella, is the best in the world. I would never work at Fox again if it weren’t for Tony Sella and his marketing department. I don’t like working over there, but no matter what a nightmare they are, I know I’m gonna make the movie and he’s gonna sell the shit out of it. But basically, all the people who work for Tom Rothman are scared of him. You’ve gotta have a spine to work there because they’d rather work with first-time or unknown directors. They like to control things. They’re control freaks. What I don’t like about Fox is the atmosphere. Everyone there is operating out of fear. Everyone is scared of the iron fist, whether it’s Rupert Murdoch or Peter Chernin or Tom Rothman. So the atmosphere is a negative atmosphere, but the thing that would keep me coming back is Tony Sella, who is a genius at marketing. He is their secret weapon. You do a movie, and you want it to be seen by people, so he’s an important part of that process.”

Screenwriter “I completely love working there because they do what they say. They say things to you like, ‘If you get this to $50 million, we will make this movie.’ And you get it to fifty, and they make it. There are very clear operating rules. I don’t think anybody opens a movie better or stronger, particularly in the action genre. They will trade a longer movie that might give slightly more clarity to an audience for running time. In other words, they will consistently give movies between ninety and 100 minutes so they can get that fifth showing every single weekend. Then you come out and have a $112 million opening weekend, and it’s very hard to argue with that logic. It’s very clear and stable. You know who the executives are. You know you bring this to Alex, and this to Emma. There’re not a lot of places that are like that. For me, it’s all about clarity there. I have complete clarity and understanding, from day one, what they’re going after and the parameters in which it has to be achieved. I don’t think there’s anybody better than Alex Young in creating and sustaining a franchise: Alien vs. Predator 1 and 2, Fantastic Four 1 and 2, X-Men 1, 2, 3 and now Wolverine and Magneto.

“Everybody bangs up Fox for one specific reason: No one can figure out how they do what they do, as consistently as they do it, for the price they do. It infuriates every studio in town. They are the one studio that says ‘no’ to everyone — and are bizarrely respected for it. And yet, people work there over and over and over again. You’d never see Beowulf at Fox cost $200 million. That would never happen. They’d have capped that thing at $125 million; they’d have overages for everybody. No one else wants to play that kind of hardball. That’s why they’re the targets, not because they put out an inferior product. They’re the targets because people don’t like that they say ‘no,’ and are number one. And the number-one people Fox gets ‘dinged’ by are producers, because they don’t like producers. There’s not even a producer of Die Hard 4. There’s not even a producer involved in a lot of their movies. It’s all line producers. Agents hate them because the studio crushes them on all their deals. So they’re an easy target.”

Producer “They think they’re producers. Their executives think they’re producers. It comes from the top. They’re telling their executives, ‘You are the producers,’ and they have small regard for producers in general. It’s such a low regard. Even that deal they set up with the writers — you know that deal that was in the trades where the writers are going to get paid a certain amount of money to write their spec scripts, and if it gets made, they get paid in success, kind of thing? Well, there are no producers on those projects! They push their executives to think, ‘You don’t need producers; you can do this on your own.'”

Screenwriter “If I had enough weight to warrant a deal, I would consider doing it despite the fact that everyone says they’re not filmmaker-friendly. A), they know how to open movies; B), I’m really impressed with what Emma Watts did with getting some of these experienced writers to write specs, giving back the power to the writer and opening the doors to making writers writer-producers. And putting up a big sign that says, ‘Yes, we are friendly to talent.’ She made a lot of steps toward doing that, especially after the whole Jay Roach/Used Guys thing that happened. Emma hired me without speaking to me. My take was given to the director, the director called her, and when we got her notes, they were good notes. She’s kind of changing the face of the studio. She seems like a very writer-friendly person. I was hired, they paid my quote, there were almost no negotiations, they were very fair and right upfront. Then I did not interact with them until after I turned in the draft, and I was nothing but excited after I got the notes. My experience was nothing but pleasant.”

Screenwriter “Emma is a liar and an idiot. She lied, and she was stupid. She soooo didn’t respect the project. If the circumstances didn’t serve her interests rather than the project at any given time, she would immediately default to lying and manipulating — as opposed to actually working in the best way to proceed so that the project could have a chance at succeeding. I don’t trash people lightly. She actually lied to me; she actually manipulated the project I was involved in. I’ve been doing this for a long time, so I usually set out the rules and boundaries and things I’m comfortable with. Like, I would say, ‘I do not like this. You are asking me to do X. I’m telling you it is my opinion if we do X, it will harm the project and ultimately not reflect well on me because I’m responsible for X, in this case. And there’s no one to protect me. So by asking me to do X, it could potentially harm me, because ultimately it’s my responsibility.’ And she goes, ‘No, no, it’s fine, it’s fine, it’s fine.’ So I did what she told me to do, and it harmed the project and it harmed me. When I said to her, ‘Remember when I told you that this could occur, and you made me do it anyway, and now it has occurred?’ She denied that we ever had that conversation! Now it’s like The Twilight Zone. I went out of my way to frame my objection in such a specific way. For her to dismiss that by admitting only vaguely that those were the terms of the parameters I set forth now makes me even madder. Because I couldn’t have been clearer. By the way, we’re only talking about a two- or three-week span. So, three weeks ago I said this, and you’re saying that wasn’t what I said? Or you don’t remember, and now I’m fucked? Fuck you! I’d rather hear, ‘We’re firing you because we don’t like your script’ than ‘Oh, we love it,’ and then find out I’m being replaced through my agent. Just say, ‘I’m not understanding it, and we’re going in a different direction.'”

UNIVERSAL PICTURES

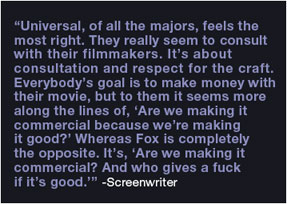

Screenwriter “Having worked with [production president] Donna Langley at Universal, they’re my favorite studio. It really seems like you have a discussion about how to make the film better. When somebody’s paying you a million dollars to write a script for them, you’d like to think that they’ll take that person’s opinion seriously and give those creative choices some weight. Some do, like Donna, at least in my experience. Some don’t care, like Tom Rothman at Fox. Universal, of all the majors, feels the most right. They really seem to consult with their filmmakers. It’s about consultation and respect for the craft. Everybody’s goal is to make money with their movie, but to them it seems more along the lines of, ‘Are we making it commercial because we’re making it good?’ Whereas Fox is completely the opposite. It’s, ‘Are we making it commercial? And who gives a fuck if it’s good.'”

Screenwriter “[I’m working on] a high-profile project with a big producer, a big director, so you’re working with the top executives. That makes things easier because you’re not dealing with a lot of development executives. It’s more on track to get made to begin with, and your notes are coming from the top advocates. That makes it a relatively pleasant experience. Donna’s very smart; she’s very literate. There are a lot of smart people in Hollywood, but sometimes they start to second-guess the audience, or they start to think purely in terms of entertainment. Donna aspires to have a wide slate of projects, and not just pawn them off on the indie division. Like, ‘Oh, it’s too artsy, let’s stick it in the indie division.’

“I feel like I’m in a more unique position on this film than other writers who are working at studios. The only downside is that when the script was delivered, and everybody liked it, there was this nervousness: ‘What do we do with this? How do we make it? Are we really going to pay this amount of money to make this film? Who are we going to get to be in this film? What’s the audience?’ All these questions. If you’re building a car, you ask these questions prior to building it. Like, ‘What’s the marketplace for it? Are people driving SUVs or hybrids?’ But these were the questions Universal was asking after the script was written, after everybody else delivered — after I delivered the script, after the producers signed off on it, after the director signed off on it. It became, ‘Well, are we going to pay this money? We had another project in this vein that made X amount of dollars, are we really going to make another movie like that?’ It’s like, ‘Well, why would you ask for this movie? Why would you ask for it at the highest level if you’re going through all these nervous questions now?’ Because it was coming in with such a prestigious package, you would think they would have asked those questions earlier. It becomes, ‘Oh, my God, what happens if we greenlight it and it fails?’ That’s where that nervousness comes from. It’s important to the producers, it’s important to the director, it’s important to the studio and everybody’s afraid to get on the plane and shoot it down the runway now. Sort of like, ‘It’s a such a pretty car, why drive it?’ But I love everybody over there, and they’re all great.”

Producer “[Marketing and distribution president] Adam Fogelson and his team at Universal are as good as anybody in the business. He’s a very thoughtful, smart, creative guy who really cares about each movie he’s marketing individually. He’s not just selling widgets. He crafts an original campaign for each movie because each movie is original. A lot of other studios will slap a campaign together. If they’re selling a romantic comedy, they just reach into their romantic-comedy bag of tricks and use all the same typeface and font on the poster. They treat every romantic comedy the same, or every action movie the same, instead of trying to make the movie feel unique in the marketplace. Adam knows how to make each movie feel unique in the marketplace in a way that other people at other studios don’t.”

Producer “What’s great about [Executive V.P., Production] Dylan Clark over there — I’d put Greg Silverman at Warner Bros. in this category too — is that even though they play politically, because they have to, they’re aware of it, and they’ll make you aware of what bullshit it is. But that’s how you get your movie made. Most studio executives I know, I wouldn’t want to spend a lot of time with, but I love spending time with the Universal guys. We hang out, we drink, we go to festivals. They’re my friends.”

Producer “Donna is very inaccessible. The executives are all trying to please her without knowing what she actually wants. Whenever there is a decision to be made, we always have to wait for the executive to get in touch with Donna, and sometimes that can take over a week — just to get an answer on something.”

Screenwriter “[Former senior production v.p.] Holly Bario was my executive there. One of those projects, I tanked. I didn’t tank the other, but it just wasn’t a movie Universal was going to make, so another studio acquired it. I actually thought my relationship with Holly would be over, but before she left [a high-profile star] called her and got me to do another project there. And yet she was not the least bit reluctant when my agents called. [Laughs] I don’t know if it was because she was leaving. [Laughs] But she seemed to understand that sometimes you miss. Disappointing her was a huge sense of failure because I have such high regard for her. When she hired me [before leaving the studio] there was such a wave of relief because I felt like I didn’t have someone out there who would hire me. It felt good because someone like Holly who is so savvy creatively is someone you, want to think well of you. I will seek her out the minute she lands!”

Director “I thought the marketing campaign [for my movie] sucked. They marketed it wrong, and I had nothing to do with it. They didn’t care what the fuck I said. They couldn’t have cared less what my opinion was. I don’t know why. They were very nice to me. I didn’t have any impact on the trailer or the poster. I would give them my criticism and they’d say, ‘Great!” and not do anything. They did not care what I had to say. It’s like, ‘That trailer sucks,’ and they’re like, “Well, it tested really high.’ Well, what are you going to say? They say it tested high, and it sucked.”

Screenwriter “I miss [former chairman] Stacey Snider. Stacey was running a very clear ship. Donna is very nice, but she’s not a very strong leader. I never know from one minute to the next what Donna’s gonna say. She’s the politics of sweet. She’s perfectly nice to me, and I can always pitch to her, but I have no idea what she wants. If she could tell me, I could probably fulfill it, but it’s like shooting from the hip with her. I have no idea what they’re doing there, or who they want to be in business with. Before, if any bullshit occurred, you could clear house with Stacey, but when Stacey left, that was all over.”

WALT DISNEY STUDIOS

Producer “Disney has become the new CAA. [Production president] Oren Aviv has got that place so completely wired already. It’s a well-oiled machine. It’s the best-run studio out there by a ton. They know what they want to do. They’re clear about their vision. They’re unapologetic about the brand, yet they’re trying to expand the brand as much as possible. They’re unbelievable. They’re cranking out hits. Oren’s aggressively putting together new movies. They’re not resting on their laurels. It’s been extremely easy because the rules are very clear because you’re working within the brand.

“Oren wants big titles, and the biggest ideas executed by the people that are most right for the project, not necessarily the biggest name. Because Disney is the biggest name. Yet he’s working with filmmakers like Tim Burton and making franchises work like Pirates and National Treasure. He’s taking internal talent like [Enchanted director] Kevin Lima and cranking out hits with them. He’s doing an unbelievable job. All the execs are accessible. They all know the rules, they all know what the Disney brand is, they all know what movies to make, and Oren is completely accessible to them. You don’t need to get to him because you know you get one clear answer. If you have a Disney-branded movie, once they lock into it, it’s getting made. You know that they’re going to do everything from every part of the company to ensure that the movie is made the best possible way for that brand. And that’s a dream.”

Screenwriter “Because Jerry Bruckheimer occupies the slots he occupies, and because Walt Disney occupies slots, every person who has a deal there, or is writing a movie there, is competing for, like, four remaining slots. You’re taking an already impossible situation and making it ludicrous. If you’re doing a movie there, you’d better be doing a straightforward Walt Disney Picture, or you’d better be doing a Bruckheimer picture. Because it is a coin toss times a thousand that anything will break through that doesn’t fall in those categories.”

WARNER BROS. PICTURES

Producer “[Production president] Jeff Robinov has got to clean out his marketing department. The marketing department is only good at selling those too-cool-for-school movies. But there are other genres out there, like comedy or family, where too-cool-for-school actually hurts the movie. So they have a real problem with marketing. [With Fred Claus, Robinov] probably knew that unless he had a $20 million actor in that movie, [domestic marketing president] Dawn Taubin couldn’t sell it. There’s a lot of unhealthy conflict between Dawn and Robinov. [President] Alan Horn does not want to engage. So it starts to turn into a blame game. Now that Jeff got his promotion, he’ll be able to work his agenda [of getting rid of Taubin]. Horn promoting Jeff was kind of like, ‘Ah, maybe I’ll look the other way.'”

Producer “Alan Horn had so little faith in 300 that he sold off not just half the movie to people on the lot, like he usually does, he sold off two-thirds of it to two different people. For a $60 million movie! Yet ironically, the movie they swallowed whole was Fred Claus, a gigantic loser.”

Producer “[Executive V.P., Production] Greg Silverman gives genuinely good notes and is a genuinely good politician, which is what you need from an executive, because they make arguments on your behalf when you’re not in the room.”

Screenwriter “Warner is good at working with big directors. They’re a lot more territorial, and you feel like executives have knives out for each other. Jeff Robinov ends up being the key decision maker, but it’s not clear that he has any taste at all. That gets to be frustrating. And on some projects, he’ll get overruled by Alan Horn. Each franchise has its own little fiefdom. [President of Production] Kevin McCormick is really good at being a cheerleader, but I never really feel like he develops the movies. He doesn’t take any ownership. He’s just the ‘rah-rah’ guy. I don’t trust him. I’m always really cautious of what I say to him because I feel like it will come back to me through a different source. His loyalty is always to protect his own place in relationship to the project. So at Warners you need a strong producer to shield you from the ‘ties’ at the studio. Polly Cohen is smart but odd. Robinov blows really hot and cold. I know there are projects that are put on the shelf forever because he’ll have a beef with somebody on the project. He’s clearly smart, but you’re never quite sure what movies he’s trying to make. He’s trying to appeal to a viewer that is not himself. All the top executives assume that everyone else in the world is different than they are, and they have to hit this magical Wal-Mart market. It gets to be really frustrating. You have to have somebody big shielding you. Have somebody involved in the project that they are eager to keep happy because they are not going to waste two seconds trying to keep you happy.”

Screenwriter “[Executive V.P.] Courtenay Valenti is hands-down my favorite studio exec. She’s the smartest and she’s the most consistent. She’s decent. She’s got great instincts. She knows exactly how to help you and how to step out of your way. When she says she’s a friend of the project, she means it, even if it means putting herself in the line of fire. If she’s a supporter of yours, you can count on it. [The project I wrote for them] was not a sexy project, and there was never a push to make it sexy. When my movie opened poorly, I got a phone call from Jeff the next morning and he said, ‘I’m sure you’re disappointed,’ and I said, ‘I am,’ and he said, ‘Well, just so you know, we’re not. This is not the kind of movie you make for big numbers; you make it for a different reason. We’ll get what we need out of it — and we get to be proud of it, too.’ That’s the kind of call you want to get from your studio. The writer is always the low man on the totem pole, and for those guys to call me like that was really nice. My stories have lately all been true stories, so there are a lot of legal issues involved with rights and stuff. Their legal department is great. They’re total collaborators. They read the book, which is amazing. They read it backwards and forwards, and sit down with you at a table and figure out what you need, and what you don’t need, in terms of rights, and then they help you get it.”

Producer “Greg Silverman actually gets excited about projects. If I have something that he wants, he’ll keep calling. A lot of executives are just looking to protect themselves. Most of them work from fear, and make decisions from fear. They don’t say, ‘Oh, my God, I’m excited about that. I have faith in it. I’d like to make that.’ They approach it like, ‘I’m gonna get in trouble if I don’t do that. And if and when it doesn’t work, on Monday morning, I can explain.’ Greg was the guy behind 300, the guy who said, ‘I know we made two sword-and-sandal movies; both of them were bad, one of them worked internationally and the other didn’t work at all, but I have faith in this guy and this movie, and I want to do it.’ And that’s rare. You don’t encounter that in studio executives. Generally they’re like, ‘How do I say no to this? How do I get out of this?'”

Producer “[Warner Bros. is] my favorite studio to work with. They spend money, and they want to make big movies. They keep saying, ‘Make it bigger!’ to try and attract the stars. Greg Silverman and [former senior v.p., production] Dan Lin tell you point-blank what needs to be done to get the movies made. They’re very upfront.”

Producer “They’re very transparent. They only want to do big, big, big — big effects, big actors, big directors, big concepts and nothing else. Those are the movies that they know how to sell. The smaller movies, regardless if they’re good or bad, they just don’t get any traction. And they’ll only do those if economically they can take a flyer on it. But they’re just not set up to do smaller movies. Greg Silverman is good, but he only wants to do one thing, so you just don’t even bother bringing him smaller stuff. And Warner Independent has not greenlit a single movie, and there are rumors that they’re about to just kill the division anyway.”

WARNER INDEPENDENT

Producer “Someone told me that they were going to shut down Warner Independent in the new year, which would not surprise me. I just don’t see the point in it. They’re not a filmmaker-driven place. Everything goes through Jeff Robinov, and it’s just a way to get actors paid a lot less money. It’s a bit of a ruse. If you’re going to ask actors to work for pennies, they expect a certain caliber of material to be made. And Warner Independent doesn’t give any back end to its actors, or anyone, actually. So it’s really hard to convince talent to work there. They have to really trust that the project will be handled correctly and it’s going to be about the art.”

Producer “It’s so controlled by big Warners. You don’t really have that artistic freedom that you want. [President] Polly Cohen is one of the smartest people I’ve ever met in my life. But she’s delegated to her executives because she’s used to working big-studio style. That’s not how those kinds of places should operate. You should have someone from the studio side dedicated to the filmmaker’s vision — someone who’s helping you to realize that vision instead of a committee decision filtered though an executive who’s afraid to have an opinion. It is big-studio style imposed on Warner Independent.”

Producer “I got stuck between the [former Warner Independent president] Mark Gill and Jeff Robinov ‘problem,’ and our film got shoved under the carpet. Pretty much every film that was a Mark Gill legacy, after he left, was put in the trashcan. It’s not a fair assessment of Polly Cohen, because it’s nothing she did deliberately. It was the mandate from Robinov. But it was heartbreaking. It took me a long time to get that film made, and it was a difficult process. I’m very proud of it, and it was depressing to see how very deliberately they didn’t support it.”

WEINSTEIN COMPANY/DIMENSION FILMS

Producer “[Co-chairman] Bob Weinstein is one of the more unpleasant people I’ve ever dealt with. He can be very nice or very mean in the span of one week. Whatever he said may not apply the following week. Like, he’ll say he’s looking for a certain type of project. For example, let’s take voodoo. He’ll say, ‘I want you to find me a voodoo movie, and this is a very important thing for us to put together.’ So you spend the whole week trying to put stuff together, and the next week he’s like, ‘What the fuck are you talking about? Voodoo is dumb. This is a stupid idea.’ And the whole time you were trying to do exactly what he wanted you to do.”

Producer “The weakest aspect of working at a studio is this corporate decision-making by committee. With [co-chairmen] Harvey [Weinstein] and Bob, there’s none of that corporate decision-making by committee. It’s one man’s rule. You either have to please Harvey, or you have to please Bob. If they like something, then everybody else gets in line.

“I thought that would be their greatest strength. It turns out that sometimes it was, and sometimes it wasn’t. When Harvey and Bob are on your side, it is truly amazing, because they have the vision and the passion where they do get to do whatever they want. The thing that can be a problem is that if they don’t like something, there is no way to get around them. Ever. That’s it. And if they like something and then change their minds about it, then that’s it. Just because they like something doesn’t mean they’ll always like it, and the execs are left holding the bag, talking to writers, producers, directors, trying to explain why Bob doesn’t like something anymore.”

Screenwriter “Bob and Harvey are crazy guys, and they have to be because they are filmmakers but they’re also a studio. I’d work with them again and again just because they are who they are. They really care about their movies. They have to because it’s their money — or as close to being their money as can be. If I were a director, maybe it would be a different story because maybe I would want to be given more room. These are guys who watch all the dailies. So as a director, I don’t know if it’s the first place I’d go to.”

Screenwriter “Harvey and Bob are running a gangster operation, and they will exploit anything, at any time, for what they perceive to be their narrow definition of whatever financial goals they have vis-à-vis the movie business. I doubt they have loyalty to anybody. Historically, they’ve had amazing taste. I think of them as GoodFellas. There’s a scene in the movie where they’re really cooking. Like, they’re making some sort of marinara sauce, some red sauce. They’re slicing the garlic with razor blades, and they know how to get the most flavor out of it. So Harvey and Bob can make a really good sauce. They put the right elements together, and it’ll be the best spaghetti you’ve ever had, but it has nothing to do with their loyalty or engendering good profits. It’s just they can bully their way into getting it done.

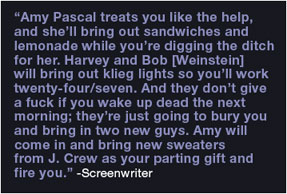

“You’re the help, and they treat you with a certain amount of contempt. Their intention is to wring as much work out of you as they can, while making you toe the line and do what they say as much as they can, while keeping you operating at a level of high efficiency. It’s a rare form of torture. In other words, Amy Pascal treats you like the help, and she’ll bring out sandwiches and lemonade while you’re digging the ditch for her. Harvey and Bob will bring out klieg lights so you’ll work twenty-four/seven. And they don’t give a fuck if you wake up dead the next morning; they’re just going to bury you and bring in two new guys. Amy will come in and bring new sweaters from J. Crew as your parting gift and fire you. She’ll fire you just as easy [as Bob and Harvey], but she’ll hope you’re alive and send you on your way. She acts like she cares. Harvey and Bob don’t give a fuck.

“They’re hurting now, because they used to have taste. They’ve always been good film buyers, but they’ve never been good filmmakers. It’s historically known that they don’t develop well. But they have great eyes to buy shit. Bob paid me tons of money [when I worked for him]; Harvey didn’t pay me a dime. And they both treated me the same. So Bob didn’t care if he was paying me a lot of money. He was still gonna treat me how he wanted to treat me. So how much they pay you is arbitrary. They don’t care. Whether you’re highly paid, or not paid at all, it doesn’t matter. They’re gonna treat you how they’re gonna treat you. People are getting sick of having to work like that. I heard Robert Rodriguez isn’t going to work with Bob anymore, but I don’t know if that’s true. I hear he’s doing his next movie at Universal, which says something.”

Screenwriter “There was this pitch I had pitched about thirty or forty times, and Bob was one of the last pitches I had. I had it down to where I knew where the guaranteed laugh lines were. I never got a chuckle out of that guy. He may be able to make great comedies by virtue of hiring people who know how to make great comedies, but he himself has absolutely no sense of humor. And he may actually know that.”