He was an undisputed cinematic artist, and several of his films are considered masterpieces, so it’s only fitting that Stanley Kubrick would be the subject of a major museum show. Fade In visits the Los Angeles County Museum of Art’s newly opened retrospective devoted to one of filmdom’s most revered “one-name brands.”

text F.X. Feeney

“On those rare occasions when he was out in public, people would rush up to tell Stanley he was a genius. Afterward, he would always turn to me and say: ‘If they just knew how much work it is!”

– Jan Harlan ( brother-in-law, producer)

Exactly how much work is laid out for the world to see at Exhibition: Stanley Kubrick, the spectacular show running now through June 2013 at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art. Eight or nine rooms — it’s easy to lose count — cover the great filmmaker’s career, from his beginnings as a boy-wonder photographer for Look magazine through his short films, early features, breakthroughs, triumphs and later masterpieces.

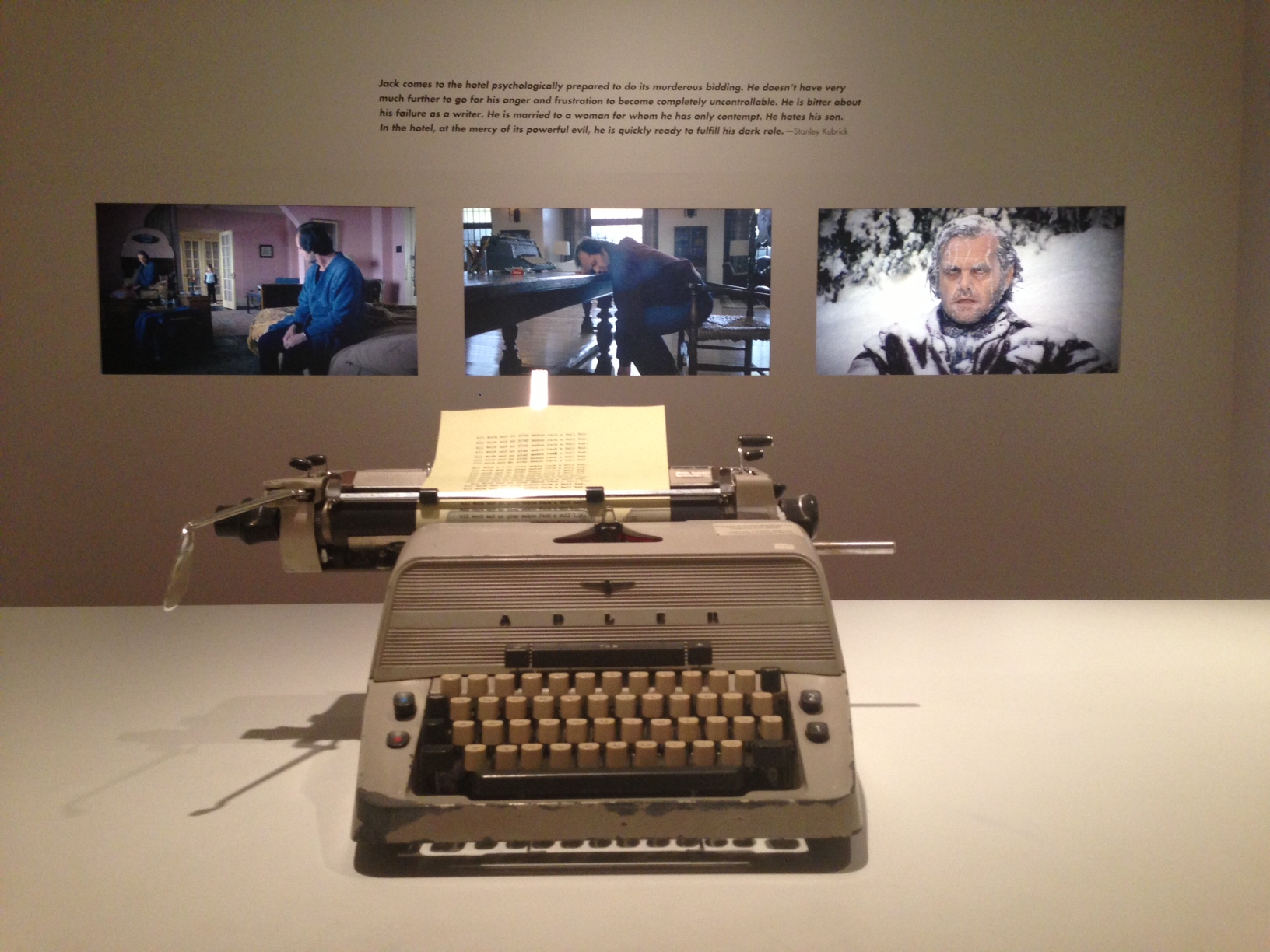

Film clips greet us from a number of obliging screens, in any direction the eye falls. Some celebrate the deep integrity of his visual sense. We jog behind the 2001 astronaut in his centrifuge, soar behind the six-year-old boy on his finned tricycle from The Shining, retreat before the French general exploring the trenches of his infantry in Paths of Glory, walk with Tom Cruise, arm in arm with two anonymous lovelies who vamp him at the sinister Christmas party that commences Eyes Wide Shut — all in seamless cuts that emphasize both the radical diversity of these stories, and their underlying continuities. The same holds for other displays of still more clips which highlight his choices of music. Again, we jump from film to film in no particular order, bridging from a Strauss waltz that leads us into outer space to the Shostakovich that invites us to explore the erotically charged inner space of an outwardly happy couple. For all the fireworks of variety, everywhere our eyes fall we find the stylish, mysterious thumbprints of the same creative soul at work.

The free play of the mind was everything to Kubrick. “I think the big mistake in schools is trying to teach children anything, and by using fear as the basic motivation,” he once famously cautioned. Curiosity was a sacred impulse to him. “Interest can produce learning on a scale, compared to fear, as a nuclear explosion to a firecracker.”

In this spirit, the exhibits filling the spaces that quietly spread through linked archways in all directions gratify every level of interest in how Kubrick developed his ideas and dealt with day-to-day problems. We’re free to gravitate where we will. He was so relentlessly logical and playful in the same breath that the cover of the script for Dr. Strangelove is covered with scribbled alternate titles: My Bomb Your Bomb, The Bomb of Bombs, Dr. Doomsday & His Nuclear Wisemen — and on and on. The screenplay for Barry Lyndon is deliberately mistitled Chance, so as to throw rival filmmakers off the scent of a Thackeray novel that was in the public domain. Kubrick’s star had risen so high, and his process was so famously time-consuming, that he feared being beaten to the screen as he’d been by Napoleon. In one display case devoted to the business end of Lolita we find letters from Kubrick to various executives and censors that illuminate precisely how he navigated Vladimir Nabokov’s shocking book to the screen without betraying it, as well as a series of patient replies to various clergymen that defend the film against their expressions of outrage on level-headed principles. Indeed, he is so firm, yet diplomatic, that what he wrote sets a powerful example to any young filmmaker — or politician; or indeed anyone — forced to master a tricky situation.

A long case in the central gallery shows off literally dozens of special lenses he either acquired or developed, including the famous Zeiss he bought from NASA so he could shoot in candlelight for Barry Lyndon. Next to these are notations of settings and his preferred “sweet spots” for minting the best images on each. (18 to 40 millimeter on one, 25 to 50 on another, 32 to 35 on yet another. Filmmakers, bring your notebooks!) A vast antique library at the back of the exhibit, whose lighting evokes an afternoon in autumn, shows off the more than 500 volumes of research Kubrick gathered to study Napoleon Bonaparte, along with lavish production sketches, detailed shooting schedules and other rich relics of a tantalizing masterpiece-that-never-was.

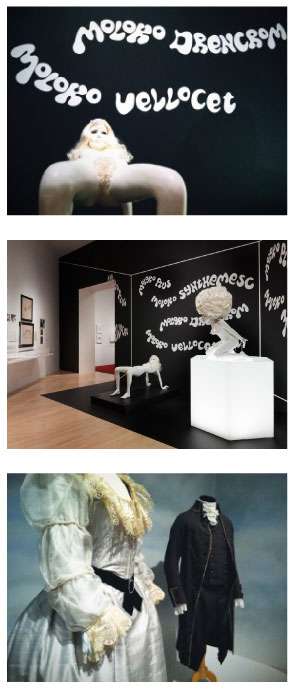

Another room details his efforts to make a film of Louis Begley’s novel Wartime Lies, in the early 1990s, under the working title Aryan Papers. A screen in a neighboring alcove runs a series of costume tests from A Clockwork Orange, in which we find Malcolm McDowell modeling various top hats, eyelashes and other flashes of fancy Droog-wear that didn’t make it into the final film.

This exhibit could have been subtitled The Logic of Creation. There’s a distinct purpose behind every object. Yet the purposes are so varied that only one particular mind would have pursued this multiplicity of goals in quite this way.

“Stanley had a reputation for exerting control,” his longtime co-producer (and one-time co-star of Barry Lyndon) Leon Vitali told Fade In with a smile on the special preview day of the exhibit — happy to admit that control is an understatement. “What people lose sight of is that by ‘controlling,’ Stanley was protecting his ability to discover, to be surprised. Our set burned down on The Shining, and his attitude was, ‘What can you do?’ But show up without the lens he asked for, and you were gone.”

Kubrick’s creative energy was so great that he attracted talents of the highest order to work with him, including: Vitali, McDowell, Nabokov, Begley, Zeiss and Harlan. For that matter, Arthur C. Clarke, Peter Sellers, Kirk Douglas, Sue Lyon, James Mason and Ryan O’Neal. You name them — their stories and creative gifts are all here on vivid display, too.

“This moment closes the cycle of my life,” his widow, Christiane Kubrick, told the crowd of admirers as she welcomed them to the preview. “Exactly fifty-five years ago in November I came to America to marry Stanley. I knew I would never be alone again. I idolized him in many ways. He would be embarrassed to hear me say this. And yet — look at all of us, here, celebrating him in this incredible and confident setting! Look at how my brother, Jan Harlan, now flies around the world in Stanley’s honor because so many people everywhere celebrate him! Stanley would be happy. Perhaps he is.”

Prior to Christiane, the person who knew Kubrick best was producer James B. Harris. The pair joined forces in their early twenties, bonded like brothers and made each other wealthy across a string of exceptional collaborations: The Killing, Paths of Glory and Lolita. Harris can remember only too well what an uphill battle it was to build their audience in the backward-facing mindset of 1950s Hollywood. He is particularly tickled by the size of the crowd wandering the displays and bowing their heads worshipfully over the contents of the cases.

“This is more people than ever showed up for either The Killing or Paths of Glory back when they first opened,” he says with a laugh. “Where were you folks when we needed you?” More seriously, he marvels at a display posted by the museum curators that elevates his pal to the status of a “one-name brand” on the level of Picasso and Chanel. Yet he agrees that it’s richly deserved. “I was here way back when for the big King Tut exhibit,” he says, “but Stanley’s is bigger — and there’s much better stuff!”